|

Looking At History: Indiana's Hoosier National Forest Region, 1600 to 1950 |

|

HISTORY IN THE MAKING

The cultural history of any region is an unfinished story, and in this way the Hoosier National Forest region is no exception. As evident in our many references to gaps in knowledge, collecting and interpreting historical information is an ongoing endeavor.

The making of history in our region is not simply the responsibility of a few historians and archaeologists, or public agencies and historical organizations. While such individuals and institutions are vital to the preservation of our past, the general public participates and contributes in many ways:

|

| Figure 102: Students from Perry Central Middle School screen excavated soil at the Rickenbaugh house. |

The Forest Service and the Public

As with other federal agencies, the U.S. Forest Service's commitment to heritage resources was initiated with the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. From this mandate, professional archaeologists and historians working for the Hoosier National Forest began systematically to identify and protect significant historic sites and structures on forest lands in advance of planned alterations--timber cutting, road and pond construction, etc. The Hoosier National Forest also nominates sites to the National Register of Historic Places, if they are considered eligible.

... interpreting the past is something we all do; at the dinner table, with our friends, over the backyard fence.... Even when we encounter a history lesson or museum exhibit, we compare it to our own memories and other accounts we have heard. [136]

|

| Figure 103: Students record the specific locations and types of artifacts found in the excavation at the Rickenbaugh house. |

The Hoosier National Forest also has worked with local groups to provide public participation in researching heritage sites. For example, students in Perry Central Middle School, in Perry County, worked with the Forest Service archaeologist to excavate areas around the Rickenbaugh House, so that historic information could be gained before new downspouts and drains were installed underground. Another Forest Service program, "Passport in Time," or "PIT," provides hands-on experience for adults and students who would like to join research and preservation projects and to assist with site surveys, archaeological excavations, and site stabilization.

The Public Role

There are many ways in which citizens can and do play a part in discovering and documenting our heritage. We list some here, and we also recommend that readers contact their local historical groups or libraries to learn more about the role they can play in compiling historical information. Many area groups and individuals are very active in exploring and interpreting our region's history, as is evident in the number of recently published works written or sponsored by these groups. [137]

Archaeology

The "ordinary folk" of history in our region have left a scanty written record about everyday life, and so archaeological evidence is vital for understanding our past. The remains of houses, farmsteads, businesses, churches, and schools are all archaeological sites. As research and interpretive programs at Colonial Williamsburg and other properly studied historic sites have shown, artifacts, architectural features, and their contexts can tell us about human achievements and transformations that would otherwise be unknowable.

With our present knowledge, it is impossible to answer all the questions people ask about the historic archaeology of our region. Where are the earliest pioneer sites? Where is the location of the old homestead of a particular family? How many historic archaeological sites are there in south central Indiana? These are just a few of the questions we cannot yet answer. Archaeological surveys have covered only a very small percentage of the landscape in our region, and most of the area explored so far has been on Hoosier National Forest lands. We estimate that roughly 95 percent of the historic sites in south central Indiana are still to be discovered.

On occasion, programs at archaeological sites are organized to offer the public a chance to participate in research. In addition to contributing to the study of these sites, people in our region can--on their own--help discover and document sites in the Hoosier National Forest and on privately owned lands.

1. You can join an organization of avocational archaeologists. There are at least two of these organizations which have an interest in research and public participation projects in our region: The Wabash Valley Archaeological Society, and the Indianapolis Avocational Archaeological Society. These groups train members in the proper methods of site survey, excavation, laboratory analysis, and artifact curation. They also hold meetings and sponsor lectures, obtain permits for their own scientific investigations, publish newsletters, and welcome new members from throughout the state (see the list of organizations provided below).

|

| Figure 104: Members of the public may know about or come across the remains of historic structures, such as this fallen chimney. If they report their findings to archaeologists, the historic site is recorded and a detailed field check can be made. Through such discoveries, an expanding set of archaeological and historic information is being developed to help us know more about the past of our region. |

2. Because so many archaeological sites are still to be discovered, you should report any evidence of historic habitation or use that you know about or come across. Even if it turns out that a site has been previously recorded, what you observe about the site's current condition can be very helpful as an "update" for the site record. The locations and descriptions of archaeological sites are kept on record at government agencies and universities.

In our region, you can report site information to the Forest Service archaeologist in the Bedford office of the Hoosier National Forest, or to the Indiana Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology in the Department of Natural Resources in Indianapolis. Such reports are needed for sites located on private property as well as on public lands, because full information is essential to understanding regional history.

The climate and architectural traditions in our region result in very few remaining historic buildings: once abandoned, structures built from logs and boards do not last long, and all we have left are the archaeological components. Therefore, fragments of bottles and crocks, chimney falls, stone blocks used as house foundation stones, even daffodils and yucca plants are clues to a historic home site or farmstead.

3. You can be a "steward of the past," helping preserve the past for the future. Archaeological sites are a "non-renewable" resource: when sites are destroyed or damaged by vandalism or construction, the information they might have provided is gone forever.

Do not collect or even move artifacts at archaeological sites. Archaeological sites are fragile resources. Contrary to the popular notion that ancient places lie buried beneath the ground surface, historic archaeological sites in our region are typically concentrated on the surface and in the upper few inches of the soil. Even minimal earth-moving or artifact ("relic") collecting can drastically harm a site for serious study and public knowledge.

It is illegal to excavate artifacts in Indiana except as part of an approved archaeological research plan. Digging at archaeological sites on federal lands without a permit is a serious crime, under the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 (and amended in 1988). Digging without a permit--or "looting"--is also illegal under state law, on state and private lands.

If you should come across signs of digging or other damage at any archaeological site, you can help save it from destruction. Contact the archaeologist or the law enforcement officer at the Forest Service office in Bedford, or a State Conservation Officer at any county office. Please, do not attempt to stop looters yourself.

Family History

Much of our history comes from documentary resources. For the study of a region, family histories in particular can help us understand culture changes and appreciate the social and economic trends that make the region distinctive.

1. Family papers are "primary" sources of information that are seldom carefully collected and preserved for the future.

You can find out how to preserve and curate old letters, photos, diaries, and documents from your local historical association or museum.

You might also consider putting together a family history based on these resources, as well as on genealogical research and family memories.

2. Genealogical research is done in every county in our region. Courthouses keep records of births, deaths, and land and tax transactions. U.S. government census data also help historians track families as they moved from one location to another. Public libraries and many local organizations can direct you to other sources of information, such as cemetery records and the family history reports written by others.

Your own genealogical research can help others if you deposit a copy of your family history with the local historical museum, library, or historical society.

Oral and Personal History and Material Culture Artifacts

Memories and physical objects also contribute to knowledge and appreciation of our heritage.

1. We have few first-hand accounts of times past. Local historical organizations can provide advice on collecting oral history and memoirs. The Indiana Historical Society and the Oral History Research Center at Indiana University, Bloomington also can be consulted.

|

| Figure 105: Old photographs, such as this early 1900s view of the general store at Paynetown, near present-day Lake Monroe, not only help document former buildings but also illustrate past lifeways. |

You can write down or tape record your own memories--or those of your older relatives and neighbors, if they are willing.

2. Local historical museums are anxious to preserve objects that help tell about regional history. Paper resources (diaries, photos, old newspapers, family records) that you may wish to have permanently preserved would be welcomed by local museums. In addition, more durable artifacts--household goods, clothing, tools and farm equipment, from the pioneer era through the 1950s--also need proper care to be preserved.

Artifacts are particularly important to museums for research and displays when there is documentation that can place objects in their historical context: Who used them? When? Where? Maybe even: Why? or How? An artifact, such as a butter churns that is acquired at a flea market, may be an interesting object as an example of a type, but it has been separated from its place in history. In contrast, you may be able to discover information that would provide a meaningful context for "some of those old things" in your attic, basement, barn, or shed by talking to older relatives or friends who may remember their use.

You can ask museums for advice on the importance of an artifact as a "piece of history" for research or education. Museums also can help you figure out the best way to document your family artifacts and to make sure their historic context does not become lost to future generations.

You can make donations to museums of material culture items and information on context that fall within the scope of their collections. (We should not forget that the present will be history for future generations: some museums, such as the Monroe County Historical Museum, are actively collecting artifacts representing the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.)

It is important to make sure a museum or society is well equipped and staffed to care for donated materials. Some organizations may lack the space or expertise to preserve the types of artifacts and records you wish to have protected.

3. Houses, farm buildings, and other structures can tell much about past times, as we have shown. Recording the form and the building techniques of older structures in detail requires some specialized knowledge, but basic description can be accomplished by anyone. Construction techniques and architectural elements are defined in many reference works. We recommend A Field Guide to American Houses by Virginia Savage McAlester and Lee McAlester (New York, 1984) for clear definitions and helpful illustrations of housing styles, elements, and terms.

You can compile a description of a historic house or other structure that you own, or is part of your family's past. As with other forms of material culture, information about the social context of a house is important in understanding its role in local history. What date was it built; who built it; where were the materials obtained; when and why were additions or other changes made; how many people lived in it; what other buildings stood (or still stand) nearby; has the structure's use changed over time; how were the grounds landscaped?

Reports which describe historic buildings and their social context can be deposited at the organizations we list. Such reports are especially useful when accompanied by photographs or drawings and location maps.

|

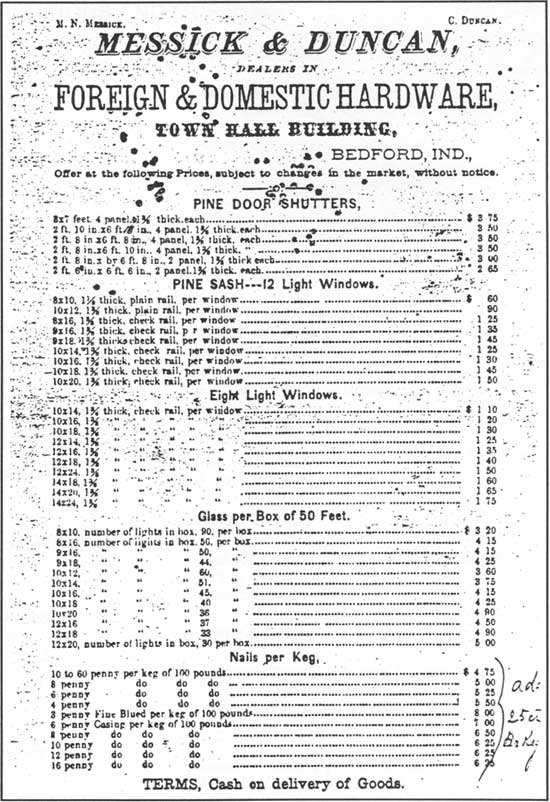

| Figure 106: This 1871 price list from Bedford hardware store is one example of the types of records local museums are anxious to preserve. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

9/hoosier/history/sec2.htm Last Updated: 21-Nov-2008 |