|

POSSIBILITIES OF SHELTERBELT PLANTING IN THE PLAINS REGION

|

|

Section 3.—THE SHELTERBELT ZONE: A BRIEF GEOGRAPHIC DESCRIPTION

By F. A. HAYES, senior soil scientist, Bureau of Chemistry and Soils

CONTENTS

Position and dimensions

Climate

Topography

Northern section

Central section

Southern section

Forest and grassland

The shelterbelt zone is not a naturally molded geographic entity like an island, a river basin, or a range of mountains. It cuts across both geographical boundaries and State lines. It is an administrative area whose bounds are defined by an economic and social objective.

Nevertheless, the location and the limits of the shelterbelt zone had to be submitted to one critical test of nature—the possibility of growing trees. The adaptation of the project to a practicable geographic framework was therefore a matter of primary and urgent importance, involving intensive studies or special surveys of certain conditions—soil, climate, topography, ground water, vegetative growth, and others—throughout the general area in which shelterbelt planting was and is desirable; all to the end that the zone delimited for operations should present a satisfactory working balance between needs and possibilities, such as would insure optimum results for the undertaking as a whole.

The results of these various investigations are recorded in their proper places hereafter. A thorough consideration of the findings, as made, raised many questions—what rainfall should control, what soils should be avoided, what native plants should serve as "indicators", what areas could or must be left without protection, and the like. In studying these various problems, the zone was several times adjusted or shifted for miles in one part or another. It was extended, contracted, deflected, or straightened as conditions seemed to dictate, so that the present outlines differ materially from the tentative pattern with which the study began and which may have been noticed at earlier or later stages of its development in various newspaper accounts.

Even so, the zone should now be understood as nothing more than a projection or ground plan of certain natural conditions. These are conditions that evidently combine to insure the successful planting and growth of shelterbelts—within the region that most needs them and under the methods which the Forest Service proposes to follow in establishing them. Inside this zone, land acquisition for shelterbelt planting can proceed as the speed of the project requires; but the area is not yet so definitely fixed by metes and bounds that it cannot be further altered or modified, should sound and advised judgment later so dictate.

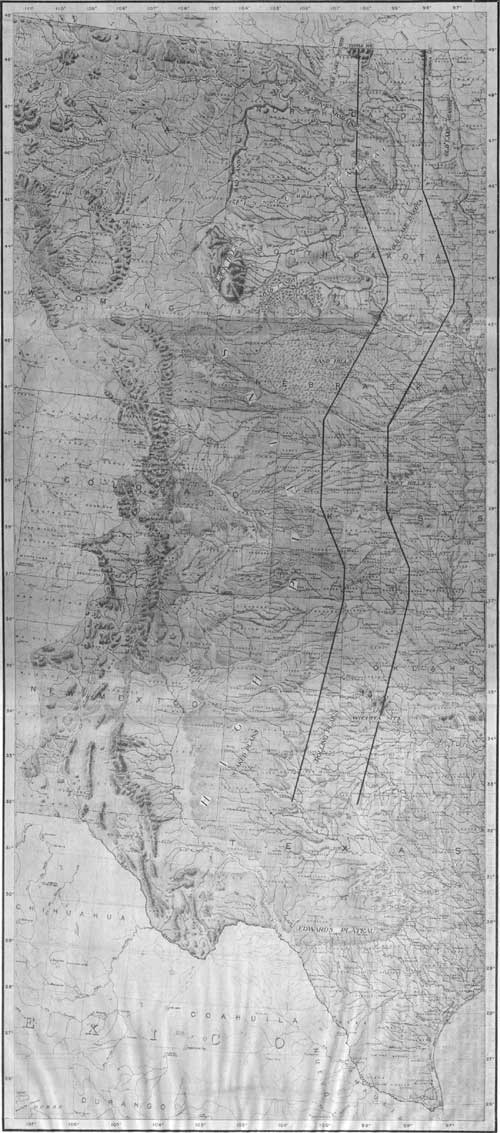

The results of the location process thus far will be seen in figure 3, in which the zone boundaries are superimposed on a relief map of the Great Plains region. This map will afford the best background for a brief geographical summary of the zone itself.

|

| FIGURE 3.—Relief map of the Plains region, with shelterbelt zone boundaries superimposed. (click on image for a PDF version) |

POSITION AND DIMENSIONS

The shelterbelt zone extends from the Canadian boundary of North Dakota to a line just north of Abilene, in Texas. In the extreme north it centers approximately on the ninety-ninth meridian, and it does not depart entirely from that meridian except for about 100 miles in the extreme south, where the departure is westward.

The width of the zone is everywhere 100 miles from east to west; its length is approximately 1,150 miles. It includes portions of North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas.

CLIMATE

The climate of the shelterbelt zone is of the middle-latitude, continental type characterized by a wide range in temperature, a rather low precipitation which decreases westward, and a high rate of evaporation.

In the northern part, the winters are long and cold, and the summers hot; the spring is cool and rainy, and the fall is long, with moderate temperatures and only occasional rainfall. The mean annual precipitation is 24 to 16 inches (east to west). The mean annual temperature is about 36° F., and the free-water evaporation loss during the warm season averages about 30 inches. The soil remains frozen to a depth of 3 or 4 feet for long periods during the winter months.

In the southern part of the zone, owing to lower latitude and proximity to the Gulf, the temperature range between summer and winter is less pronounced. Erratic temperature changes are common, however, particularly in the winters, on account of "northers", which may cause fluctuations as great as 50° or 60° F. within a few hours. The mean annual precipitation is here 29 to 22 inches, east to west; the mean annual temperature is about 60° F., and for the warm season, the free-water evaporation is approximately 53 inches. During the winter the soil freezes intermittently, but only for short periods and seldom to a depth greater than 1 foot.

In the central part of the zone, climatic conditions are intermediate between those existing in the northern and southern parts.

Of climatic factors, the two most potent in enforcing the need for shelterbelt planting are drought and wind. These phenomena are discussed fully in the later section on climatic factors. It need only be said here that the zone, as a whole, is open to the almost constant sweep of winds; and that it is subject to recurrent droughts of protracted and culminating intensity, aggravated by the nonreceptive character of many of the soils. (See also, section on Soil and Forest Relationships, pp. 111 to 153.)

In the north, winds and cold weather have long taught the lesson of the shelterbelt's value to the farmer and his stock. Recently in both North and South, drought, dust, soil blowing, and the mortality of many groves has given the impetus to better planned, better organized, and generally more scientific shelterbelt planting and maintenance. Everywhere, planting will have to be guided by due regard to species and soil, and care of the growing trees must follow the lines laid down by successful experience in similar situations.

TOPOGRAPHY

The general surface in the region which includes the shelterbelt zone is a broad, nearly level to hilly plain, sloping gently eastward from the Rocky Mountains. Most of this plain is mantled with deposits of varying thickness laid down in past ages by ice sheets, water, or wind, although some areas occur in which the bedrock is at or near the surface. The plain is crossed by several major streams flowing eastward or southward, including the Missouri, James, Niobrara, Platte, Arkansas, and Canadian rivers, all of which have carved rather deep valleys. Tributaries to the rivers have produced considerable bodies of rough land. Strips of flat alluvial land occur along the drainage ways.

Practically the entire region has good surface drainage; in the rougher parts run-off is rapid, and erosion may be severe. Extensive areas are so nearly level that surface drainage is slow and erosion is negligible, but the only poorly drained areas are on the bottom lands and in numerous small depressions on the uplands and terraces.

NORTHERN SECTION

The part of the zone lying north of the Nebraska-South Dakota boundary, comprising approximately the northern one-third of it, has a typical glacial topography. It is characterized as a whole by a generally rolling surface, modified in many places by rough morainic hills and ridges, large areas of nearly level land, and numerous basinlike depressions formerly occupied by lakes or ponds, some of which still contain water.

The most prominent features of this section are the Altamont Moraine, the Turtle Mountains, and the old basins of glacial Lakes Souris and Dakota (fig. 3).

The Altamont Moraine in North Dakota crosses the western boundary of the shelterbelt zone about 100 miles south of the Canadian Border and extends in a general eastward and southern direction to the South Dakota line, where it returns westward nearly to the Missouri River. Across South Dakota it follows the east littoral of the Missouri, in a very meandering and indistinct course, marked by numerous lobes. It crosses the eastern boundary of the zone at the southeast corner of South Dakota. This moraine marks the western and southern margins of a major glaciation. In North Dakota it forms a fairly continuous rough belt, 10 to 15 miles wide, of boulder-strewn hills and ridges, some of which rise several hundred feet above the smoother bordering lands. In South Dakota it is represented generally by a broad, slightly elevated, and strongly rolling to hilly belt distinguished from the surrounding land mostly by its rougher and more stony surface. It has definite local development, however, in counties all along the western boundary of the zone; in these places its surface is comparable to that of its rougher portions in North Dakota.

The Turtle Mountains are a high, plateaulike area at the extreme northwest corner of the shelterbelt zone. This area is an outlier of the old Missouri Plateau, from which it was separated by differential erosion. It stands 400 to 600 feet above the surrounding land and is occupied by numerous morainic hills and ridges and a number of lakes. It is mostly forest-covered.

The Souris and Dakota Basins represent the beds of lakes formed by ice barriers which blocked the drainage ways during the glacial period. The Souris Basin lies largely west of the shelterbelt zone and extends into Canada. The bed of Lake Dakota is a broad north-south basin extending across the zone in the north half of South Dakota and terminating across the North Dakota line. Stone-free sediment carried into these lakes was spread evenly over their beds. The more silty and clayey sediments occupy almost level areas, but the sandy deposits have been whipped by wind into a choppy, dunelike topography in many places.

The ice-laid material which covers most of the shelterbelt zone through the Dakotas is variable in thickness and composition. It consists chiefly of clay, silt, and fine or coarse sands mixed in varying proportions from place to place. Gravel and boulders of various sizes are usually present, in some localities comprising the bulk of the material. The deposit is very limy, frequently containing as much as 10 percent of calcium carbonate.

Along the Missouri River, generally west of the zone, erosion has removed the glacial mantle and severely acted upon the underlying Cretaceous shales known as the Pierre formation, producing an extremely rough and broken topography. Within the zone the only intrusion of this formation, with its extremely difficult soils, is a sharp salient occurring at the South Dakota-Nebraska line.

CENTRAL SECTION

The central section of the shelterbelt zone, as hereafter referred to, may conveniently be considered as that part lying in Nebraska and generally north of the Arkansas River in Kansas. It includes parts of the sand-hill areas in Nebraska and of the loess-mantled plains which cover most of southern Nebraska and northwestern Kansas (fig. 3). Areas of uplands capped either by gravel or loess occur in the extreme northern part of Nebraska, and a considerable body of sandy, naturally subirrigated hay lands lies within the zone northeast of the main sand-hill area.

Apart from the sand hills and dissected areas bordering valleys, the central section of the zone has a nearly level to gently rolling surface, dotted by numerous shallow depressions in which storm water accumulates. It is crossed by the broad and rather deep east-west valleys of the Niobrara, Platte, Republican, and Smoky Hill Rivers and is further dissected by their tributaries. Most of the tributary valleys are narrow, shallow, and widely spaced, but in several large areas they are close together and sharply incised to depths ranging from 30 to more than 100 feet. The latter conditions are especially pronounced along the Republican Valley in southwestern Nebraska and in adjacent areas of Kansas. Here the prevailing level terrain is altered to a series of narrow, flat-topped upland tongues, separated by drainage ways whose canyon walls are often nearly vertical.

The sand-hill region comprises an outstanding feature of the Nebraska topography. It occupies more than 20,000 square miles of that State and consists of a series of irregularly distributed hills and ridges separated by valleys and pockets. Lakes or ponds occur in many of the lower situations. The sandy material is unstable, but, owing to its native grass cover, it is not subject to destructive wind erosion except locally.

Another striking feature of the shelterbelt zone in southern Nebraska and northern Kansas is the vast expanse of level to slightly rolling country mantled by loess. The loess consists of wind-blown material—mostly a fine, floury silt—deposited during Pleistocene times, the original source of which was loosely consolidated Tertiary formations to the west. Uncounted billions of tons of this material were blown in upon previously existing land forms, tending to level out the relief by thicker accumulations in the lower, more protected areas, and to create a generally flat topography. The soil is fertile and thoroughly adapted (in normal seasons) to wheat growing, which prevails on a tremendous scale. These loess soils, as a whole, are listed in the difficult class for tree growing, yet they include many areas where trees have been and can be planted with success. (See Soil and Forest Relationships, pp. 111 to 153; also, Review of Early Tree Planting Activities, pp. 51 to 57.)

SOUTHERN SECTION

The southern section of the shelterbelt zone includes parts of central and southwestern Kansas and western Oklahoma, a narrow sector of the Texas Panhandle area, and part of the northwestern section of Texas known as the "rolling plains." The typical High or Staked Plains, an extremely level formation similar in surface features to level lands in the central section, have been left largely outside the zone in Texas (fig. 3). They are developed on rather fine-textured Tertiary materials. These High Plains, with several interruptions, extend northeast across western Oklahoma to the Arkansas River in southwestern Kansas and, less distinctly, beyond.

The rolling plains lie several hundred feet below the High Plains to the west and are separated from them, especially in northern Texas, by a steeply sloping and extremely gullied escarpment, generally known as "the breaks." The land east of the escarpment is roughened by numerous drainage ways. Its surface is strongly rolling to hilly, with a general eastward slope. Here prolonged erosion has in most places removed the thick Tertiary deposits upon which the higher plain is formed and also the immediate underlying formations down to the "Red Beds" of Triassic and Permian age. These consist chiefly of red, limy, soft sandstones and sandy shales, containing in places rather thick beds of gypsum. Over large areas, they lie at such shallow depths that they give the land a decidedly reddish color. In many places wind and water have removed the finer materials from the surface of the Red Beds, and the residual sands have been piled by the wind into hills and ridges, creating a topography similar to that in the Nebraska sand hills, but less extensive. At present, a negligible part of the sand is subject to active wind erosion.

FOREST AND GRASSLAND

The native vegetation of the shelterbelt zone consists mainly of grasses. Woodland occurs in narrow, intermittent strips along all the larger and many of the smaller drainage ways. It also covers most of the area occupied by the Turtle Mountains, as previously noted. Elsewhere there are few trees except in some of the situations where the water table is within reach of tree roots and on some of the more sandy lands, where the moisture is sufficient to support tree growth even during prolonged droughts. Trees, largely of native stock, have been planted at many places, notably in the Nebraska sand hills, where a national forest and a tree nursery have been successfully established. (See Review of Early Tree Planting, pp. 51 to 57.)

Native grasses include both the tall and short species characteristic of mixed prairie. The distribution of these species is determined largely by the amount of the precipitation and the effectiveness of soils in absorbing and holding the water which falls on them. These factors, and the importance of the mixed-prairie grass type as delimiting the westward reach of the shelterbelt zone, are particularly noted under Soil and Forest Relationships of the Shelterbelt Zone and Native Vegetation of the Region (pp. 155 to 174).

In the eastern part of the zone where precipitation is highest, and in the northern part where the evaporation loss is relatively low, practically all the soils not otherwise used are able to support a dominantly tall-grass cover. This cover decreases in density southward, in accordance with the diminishing effectiveness of the precipitation in response to a greater evaporation loss.

In the zone proper, tall grasses are dominant only in valleys and on sandy soils, generally giving way westward to short grasses through the relatively narrow transitional zone of mixed prairie. Large and dense stands of tall, sod-forming grasses, such as occur in the big-bluestem prairies of Minnesota, Iowa, and Missouri, are rarely seen on typical upland soils, the nearest approach to such a type being found at the northern end of the zone and along its eastern edge from Kansas northward. Even here, on most of the heavier soils, the tall grasses intermingle with or give way entirely to grama grass. Along the east side of the zone, from about the Nebraska-Kansas line south, dry soil conditions brought about by a high evaporation have forced the tall grasses, chiefly prairie beardgrass, to assume the bunch habit of growth. To the west, grama and buffalo grasses become increasingly dominant as vegetative conditions verge closer and closer upon those of the typical short-grass country.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

shelterbelt/sec3.htm Last Updated: 08-Jul-2011 |