|

POSSIBILITIES OF SHELTERBELT PLANTING IN THE PLAINS REGION

|

|

Section 4.—THE PROPOSED TREE PLANTATIONS—THEIR ESTABLISHMENT AND MANAGEMENT

By D. S. OLSON, in charge Planting and Nurseries, Plains Shelterbelt Project, Forest Service, and J. H. STOECKELER, junior forester, Lake States Forest Experiment Station, Forest Service

CONTENTS

Size and extent of individual shelterbelts

Supplementary planting by private effort and by States

Location of shelterbelts with relation to fields, roads, and buildings

Preparation of ground

Species to be planted

Collection of seed

Growing nursery stock

Size of trees to be planted

Time required to establish shelterbelts

Spacing of trees

Care of shelterbelts

Special protective measures

Protection against livestock

Protection against rodents

Disease prevention and control

Control of insect pests

Costs of establishing shelterbelts

The scheme of planting within the shelterbelt zone will vary according to soil types, land use, optimum benefits to be derived from various kinds of planting, and other factors. Of the gross area within the zone, much of the land will not be planted or served by planting, either because the land will be occupied by towns or cities, because landowners will not wish to lease or sell their property for shelterbelt purposes, because the land is not suitable for tree growth, or for other reasons. Three general kinds of planting are considered:

(1) The typical field shelterbelt, with which this report is primarily concerned, will be a planted strip 8 rods (132 feet) wide, comprising 16 acres in the length of 1 mile. The area of land to be acquired for such a shelterbelt, however, will be 10 rods wide, so as to provide on each side the space needed for cultivation and for the spread of the roots and crowns of the trees. There will thus be 20 acres in each mile of strip. The strip will be adequately fenced. It is estimated that 1,282,120 acres, all on favorable soils, will be planted to field shelterbelts.

(2) On more difficult soils, where the establishment of trees is likely to be more expensive, yet where the need is great, it is the plan to aid farmers through cooperative agreements in the establishment, on a cooperative basis, of farmstead windbreaks. For this purpose it is estimated that 897,880 acres should be planted.

(3) Approximately 4,099,000 acres of land within the shelterbelt zone should be placed under forest and range management to prevent erosion and to permit of the protection of critical areas from cultivation and overgrazing. Of this area, about 400,000 acres should be planted more or less solidly, the plantings varying from relatively small blocks along the river breaks to more extensive tracts, on which planting should be done for watershed protection, timber production, and other uses (see fig. 4). Table 1 shows the distribution, by States, of the estimated acreage of the first two classes of planting, and table 2 shows the distribution of the estimated acreage in the third class, also by States.

TABLE 1.—Acreages within zone proposed for shelterbelts and farm steed plantings

| State | Area for planting |

General character of area | Total |

| Acres | Acres | Acres | |

| North Dakota | 192,780 | 209,280 | 402,060 |

| South Dakota | 152,200 | 211,180 | 363,380 |

| Nebraska | 265,720 | 127,940 | 393,660 |

| Kansas | 203,860 | 190,660 | 394,520 |

| Oklahoma | 221,120 | 72,820 | 293,940 |

| Texas | 246,440 | 86,000 | 332,440 |

| Total | 1,282,120 | 897,880 | 2,180,000 |

TABLE 2.—Acreages within zone proposed for block planting and

forest management

| State | Field shelterbelts on favorable soil |

Farmstead plantings on difficult soil |

Purpose for which area is suitable |

| Acres | |||

| North Dakota | 262,000 | Turtle Mountains | National-forest purposes. |

| 21,000 | Souris Lake bed | Do. | |

| South Dakota | 197,000 | Dakota Lake bed and sandy areas. | Partial planting and range management. |

| Nebraska | 102,000 | Sand hills | Block plantings of about 25 square miles each. |

| Kansas | 307,000 | River breaks and other rough areas. | Partial planting and range management. |

| Oklahoma | 1,590,000 | do | Do. |

| Texas | 1,620,000 |

do | Do. |

| Total | 4,099,000 | ||

There is need for much investigation and scientific research. For some portions of the shelterbelt zone there is an accumulation of experience and knowledge of planting and nursery work that leaves little question as to the practicability and desirability of tree planting, or as to the methods to be employed. In other portions of the region, however, experience and knowledge are inadequate to the needs of a large and difficult project, and several years should be spent in experiment and field tests before work in such localities is developed to its full proportions. Administrative problems of some magnitude must also be solved. Pending their solution, the expansion of operations should be held within conservative limits in order to avoid waste and inefficiency.

|

| FIGURE 4.—Plantings on the Nebraska National Forest. Ponderosa pine at left; jack pine at right. (F209910) |

SIZE AND EXTENT OF INDIVIDUAL SHELTERBELTS

The length of a strip will be determined largely by the ownership status of the land, the type of soil, and the willingness of the landowner to have such plantings made. It is improbable that a single belt of trees will be continuous for more than 1 mile without a break or an offset. Gates and passageway through the belt must be provided at reasonable intervals as required.

It has already been stated that the typical field shelterbelt will be planted 8 rods wide. This does not imply, however, that plantings 3 to 6 rods in width may not be used, where belts of such width will meet all practical requirements.

Field shelterbelts, at least in the initial stages of the program will be kept a mile or more apart as a means of distributing equitably the benefits of planting.

SUPPLEMENTARY PLANTING BY PRIVATE EFFORT AND BY STATES

Many shelterbelts have been planted in the past by private effort, often supplemented by State and Federal cooperation. Most of this planting has been around farm buildings, because the farmer has felt that he would receive the greatest return from trees near his home, and because in that location he could more conveniently care for his plantings than elsewhere. Even so, the total amount of planting done thus far, either around the homes or around the fields, has been relatively small because of the cash outlay for stock and labor required in planting and cultivating, and because of discouragement following occasional failures.

Increased planting by individuals can be expected under the impetus of an organized movement. A large increase in orders was reported by nurserymen during the winter of 1934-35, this being attributed to the publicity given the Government shelterbelt project. Despite such increases, however, planting in the Plains region for years to come will in all probability be limited to areas around garden spots and farmsteads. To the east of the designated shelterbelt zone, where moisture conditions are more favorable, an increase in planting to protect cultivated fields can be expected. The latter, however, will probably not be forthcoming until benefits from the shelterbelt planting to the west are manifest, and until there is general dissemination of information on all phases of shelterbelt planting. Such supplemental planting through private or State effort can then be expected within the zone, also, and it can be expected to increase to the extent that farmers have ready money for the purchase of planting stock. Intermediate strips and strips at right angles to shelterbelts planted by the Government, subdividing farm units, will, it is hoped, be planted through such effort. Better composition and maintenance of plantations than in the past and more careful selection of the stock may also be expected. It is only natural, then, that an expansion of Clarke-McNary work should ensue, and that the State forestry departments should be called upon for more and more planting stock.

LOCATION OF SHELTERBELTS WITH RELATION TO FIELDS, ROADS, AND BUILDINGS

The Government shelterbelt will ordinarily be along quarter or forty lines in the interior of sections. In some cases the belt for its full width will be located entirely on one side of such boundary lines to simplify acquisition work. Plantings will not be placed too close to roads, because of the danger of drifting snow. Field shelterbelts will usually be confined to the better agricultural soils. The more difficult planting sites, such as coarse, droughty soils, alkali spots, claypan soils, heavy clays, and undrained basins, will usually be avoided. Some experimental plantings on such sites will, however, be made on a sufficient scale to give at least tentative solutions to the problem of selection of species, preparation of soil, and subsequent care of the plantations.

No field shelterbelt planting is now contemplated on areas that are classified as grazing land, which often occupy the rougher, more rolling, and more arid parts of the shelterbelt zone.

Shelterbelt plantings around farmsteads will be planned to give maximum protection to buildings and gardens. This will mean that their shape, composition, length, and width, as well as their distance from buildings and gardens, will have to be varied to suit conditions as found.

Prevailing wind direction will to some extent determine the orientation and location of all types of shelterbelts.

PREPARATION OF GROUND

Experience has already shown that, to insure the successful establishment of any tree planting on the Plains, the initial step is adequate ground preparation prior to planting. The purpose of this advance preparation is to reduce the drain on soil moisture by weeds, and to create conditions favorable to the absorption of precipitation and to the conserving of a reserve supply of moisture for the trees to draw upon for the first few seasons. After the trees are once established, and their crowns are sufficiently developed to shade the ground, they will compete successfully with other vegetation, and will conserve moisture themselves—through absorption and retention of water in the porous leaf litter and humus developed, through the accumulation of drifting snow, and through the reduction of surface evaporation.

Summer fallowing will be standard practice, but will be varied in application and will be combined with other measures of moisture and soil conservation.

SPECIES TO BE PLANTED

The survival, growth, effectiveness, and longevity of the shelterbelts will depend to a large extent on the proper selection of species and their use in certain combinations on the different planting sites.

Fortunately, records and observations relating to thousands of groves have been accumulated during a period of many years by various Federal and State agencies engaged in tree planting and are now available for study. An untold number of groves of various ages, planted by individual farmers, remain yet to be studied. Some farm plantings were eminently successful; others were complete failures. Much of the success or failure of past effort can be traced to one of two factors—namely, selection of species and subsequent care.

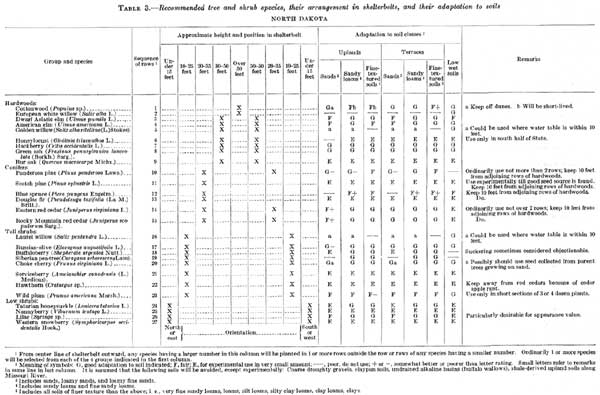

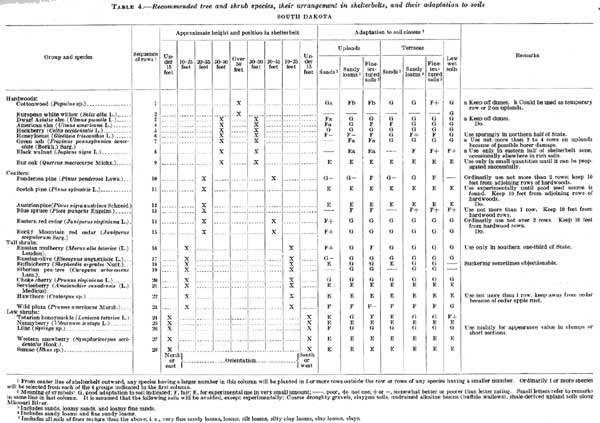

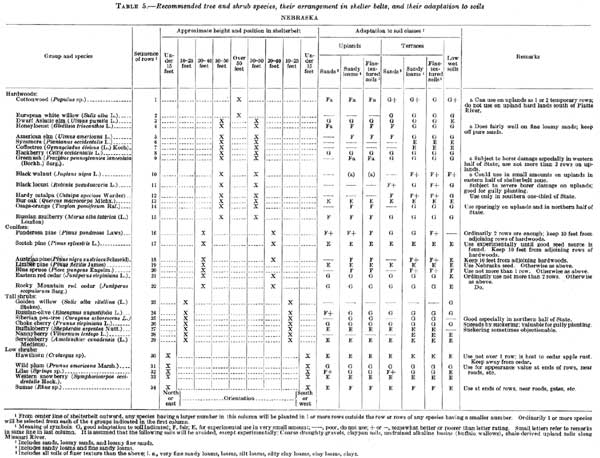

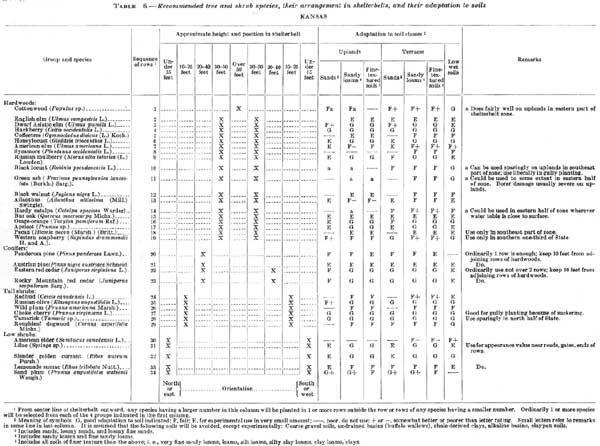

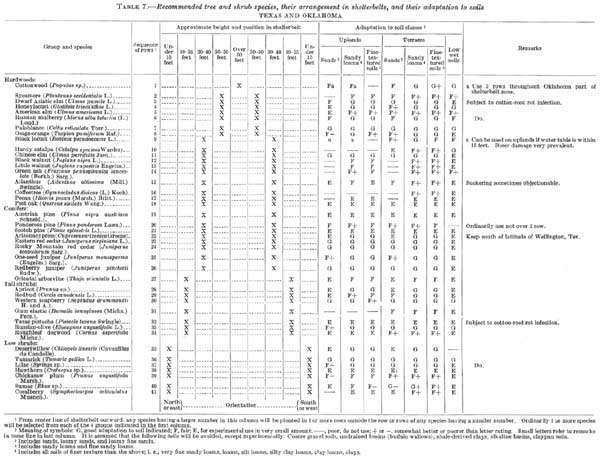

The results of wide observation and experience in the several States of the shelterbelt zone as to the adaptation of species to different soils and planting sites and their proper arrangement in the shelterbelt cross section are shown in tables 3 to 7, intended to be used as a practical field-planting guide.

(click on image for a PDF version)

(click on image for a PDF version)

(click on image for a PDF version)

(click on image for a PDF version)

(click on image for a PDF version)

The tables do not include all species that may have use in shelterbelt planting. Other species, both native and introduced, will be tried experimentally and used more extensively as soon as they prove their value in field planting.

In using the tables, the field man must first determine the soil group with which he is concerned, after which he will usually select one or more species from each of the four groups (column 1)—hardwoods, conifers, tall shrubs, and low shrubs. Selections will be limited mostly to species given ratings of G or F+. If possible, a wide variety of species should be used. Ordinarily no one species should make up more than 50 percent—preferably not more than 30 percent—of the total number of trees planted.

The table can be used for shelterbelts with a range in width from 3 to 30 rows, although the usual number of rows will vary between 10 and 20, depending on the total width of the strip of land available, the spacing of the trees, and the function of the shelterbelt.

Arrangement of species in the cross section of the shelterbelt is shown by a system of crosses (X), supplemented by a column of numbers. The positions of each species as indicated were determined largely from a knowledge of what the ultimate height of each will be under a given set of soil and moisture conditions.

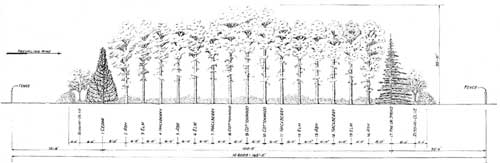

A pictorial cross section of a typical 8-rod shelterbelt, showing the relative positions and heights of hardwoods, conifers, and shrubs, is given in figure 5.

|

| FIGURE 5.—Cross section of 17-row shelterbelt on 8-rod strip, with sand trap and roadway on either side. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Among the factors to be considered in selecting species which appear in the table, besides climatic and soil adaptability, are the following:

1. Silvical value.

Ultimate height, density (value as windbreak), amount of leaf litter produced, growth rate through entire life of tree, longevity, wind firmness, resistance to wind breakage, tolerance, moisture requirement, ease of establishment in difficult years, susceptibility to sleet and hail damage, snow breakage (in northern half of zone), and sand cutting and degree of protection needed for survival and growth.

2. Economic value.

Value of wood as fence posts, lumber, or fuel; edible fruit, berries, or mints produced; value as a snow fence.

3. Susceptibility to damage.

By insects, including borers, defoliators, bark beetles, blister beetles, tip moths, and others.

By diseases; a species may itself be susceptible to a certain disease, and it may also be an alternate host for some disease of cereals, fruit trees, etc.

By rodents, such as rabbits and gophers.

4. Aesthetic value.

Certain species used in combination are valued for their beautiful appearance. This point should be given special consideration along roads, at park or forest entrances, and around buildings.

5. Value as cover and food for wildlife.

6. Cost of producing planting stock.

7. Years of maintenance necessary before cultivation can be dispensed with.

8. Special values.

In gully-control work, species such as black locust and chokecherry are valuable because they grow fast, root deeply, are excellent soil binders, and spread by suckering.

COLLECTION OF SEED

Throughout the shelterbelt zone, there are many people who supplement their farm income by collecting seed for nurseries and seed dealers. A new source of income will be opened to such persons by the shelterbelt project. Personnel will be employed for seed collection as required. By establishing a few central depots, a large quantity of seed can be collected at minimum cost.

Since nearly all of the species to be used produce seed in the fall, most of the collection work will be done in the fall and winter. Exceptions are American elm, dwarf Asiatic elm, apricot, and caragana. Seed of these species must be collected when ripe in the spring or early summer, since the seed does not remain on the trees.

Germination tests for the purpose of determining the amount of viable seed on hand and the quantity to be sown in the nursery will be made. Such tests will be made in sufficient detail to determine also for the several species the differences in viability between seed lots collected in separate localities or from representative trees. Through this information it will be possible to determine where to collect the best seed. Extraction or cleaning of the seed will be done at the centrally located seed stations. This may best be handled in connection with winter storage of the seed prior to sowing. In order to obtain satisfactory germination in the seed bed, it is necessary to stratify (layer in moist sand over winter) the following: Hackberry, bur oak, walnut, apricot, soapberry, mulberry, Russian-olive, choke cherry, hawthorn, buffaloberrys and juniper. Storage at a constant temperature for a definite length of time is desirable for some species, particularly juniper. In the absence of prior treatment of such seed, germination in the seed bed is irregular, and an additional year is required in growing the stock.

The seed used will be mostly from native trees of good form and of known climatic adaptation. Species introduced for experimental purposes will not be used on a large scale until they have been proved suitable for shelterbelt planting. Latitudinal limitations will be observed in the movement of seed from one locality to another, in order to retain the adaptation a species has acquired for a particular environment. In many cases localized collection of seed and planting of trees grown from it will be advisable.

It has nevertheless been found necessary to go outside the zone to secure a part of the seed, particularly of Chinese elms. Careful study has been given climatic conditions under which parent stock is growing, and those sources where conditions are not comparable to the ultimate location of the trees have been eliminated.

GROWING NURSERY STOCK

As a measure of efficiency and economy, full use will be made of available facilities in existing commercial nurseries. Fully developed land will be leased and will be placed under the care of nurserymen employed by the Forest Service for that purpose. Under this arrangement all operations—sowing, cultivation, irrigation, digging, and storing—will be under direct Government supervision. The importance of producing the best possible quality of planting stock justifies as complete control as can be maintained.

Nurseries outside the shelterbelt States except for rare exceptions will not be used, since the different growing conditions bring up additional problems of acclimatization, transportation of seed and stock, and supervision and overhead. The distribution of existing nurseries may not be entirely satisfactory, however, and the establishment of Government-owned nurseries may be necessary in some localities in order to eliminate excessive transportation costs. Also, it is probable that Government nurseries will be needed for the propagation of difficult species, particularly conifers, and at least one Government-owned nursery in each State is desirable in which to check costs and production of deciduous species in the commercial nurseries.

SIZE OF TREES TO BE PLANTED

The best size of deciduous-tree seedlings for the shelterbelt planting is 12 to 24 inches in height above the ground. Modifications will, of course, have to be made to suit local conditions. In the Southern States, Chinese elm 1-year stock, for example, will in some cases be more than double this size, owing to the long growing season. In that part of the region the problem will be to avoid excessive size. In the Dakotas, on the other hand, in order to obtain the desired size, it will be necessary to use 2-year seedlings of some species—for instance, green ash, American elm, hackberry, choke cherry, plum, and sumac.

Most evergreens will be produced for planting as either 2-year or 3-year stock throughout the entire shelterbelt zone. Even then they will average much smaller than the hardwood stock, rarely over 12 inches in height.

The 12- to 24-inch hardwood seedlings are desirable for shelterbelt planting because in this size the proper balance is usually obtained between roots and tops without pruning of either. When seedlings of this size are dug, the root system remains practically intact, without undue injury of any kind. Furthermore, the seedlings can be planted in the field much more rapidly and cheaply than those of other sizes. As seedlings grow older and larger, the roots spread out and when dug are mutilated or cut off, so that pruning of both roots and tops becomes necessary.

In general, it is safe to say that 1- to 2-year stock of this size will give 30 percent better survival than the larger 3- to 4-year seedlings. Root rots and other fungi often attack trees that are cut and mutilated, and eventually cause their death. It has also been observed that 12- to 24-inch seedlings will equal or exceed the larger seedlings in size at the end of several seasons' growth, a result which follows because the larger seedlings must necessarily recover from the shock of pruning and must also develop a new system of feeder roots before substantial top growth can take place.

Direct seeding of some species such as the walnuts and oaks has proved a successful means of establishing trees in parts of the region. These species develop strong tap roots in the nursery and are generally difficult to transplant as seedlings.

The use of cuttings will be limited to the propagation of low shrubs in cases where seeding is impracticable.

TIME REQUIRED TO ESTABLISH SHELTERBELTS

About 85 percent of the trees to be planted are of hardwood species, which are inherently capable of faster growth than those of the coniferous species making up the remaining small percentage. Even 3 years after planting in the shelterbelt, the faster growing species will often reach a height of 4 to 6 feet, sufficient to impede alike the movement of drifting snow and of soil. After 5 years, species such as dwarf Asiatic elm, cottonwood, green ash, and caragana, even in the rigorous climate of the extreme North, may be expected to attain a height of 8 to 14 feet and a crown spread of 4 to 6 feet, sufficient to break the force of the wind appreciably and to harbor bird life. Thus it may be safely predicted, on the basis of experience and observation, that at 5 years shelterbelts of the type planned will have become definitely established and will have achieved some degree of effectiveness, the trees being firmly rooted and their crowns sufficiently developed to form a nearly continuous canopy, sloping to the ground on each side of the shelterbelt, Cedars and shrubs of lower growth will be planted in the outside rows.

SPACING OF TREES

Spacing of trees within the belt will not necessarily be identical throughout the zone. Experiments conducted by the Northern Great Plains Field Station of the Bureau of Plant Industry at Mandan, N. Dak., show conclusively that, under the conditions of that section, a relatively close spacing is much superior to wide spacing. This conclusion is substantiated by field observations of groves planted by farmers in both North Dakota and South Dakota. In Nebraska and southward a slightly wider spacing is recommended.

In the Dakotas, interior rows of deciduous trees will be planted 4 to 6 feet apart in rows 8 to 10 feet apart; conifers and tall shrubs, 4 feet apart, in rows 8 to 10 feet apart; low shrubs (in outside rows) will be 2 to 4 feet apart in rows 8 feet apart.

From Nebraska southward through Kansas and Oklahoma and into Texas, interior rows of deciduous trees will be planted 4 to 6 feet apart in rows 8 to 12 feet apart; conifers, 4 to 6 feet apart in rows 10 to 12 feet apart; tall shrubs, 4 feet apart in rows 8 to 10 feet apart; low shrubs, 2 to 4 feet apart in rows 8 to 10 feet apart.

It has been observed that relatively close spacing usually assures, in a much shorter time than is required with wide spacing, a "forest cover" condition, in which the competition of grass and weeds inside the grove is reduced to a minimum by the closed crown canopy and the mulch of leaves and litter formed on the ground. The sooner the crowns of the trees begin to interlace, the sooner cultivation of interior rows, which is an item of appreciable cost, can be dispensed with. The outside of the strips will, in many instances, have to be cultivated for the entire life of the grove.

One of the most important factors in attaining a mulch of leaves and forest litter is the establishment of several outside rows of dense, low shrubby growth of species like caragana or choke cherry. This is absolutely necessary if any considerable portion of the fallen material is to be retained in the grove; otherwise, leaves will be blown out by the wind, exposing the ground to evaporation and the invasion of weeds and grass whose presence will materially shorten the life of the trees.

CARE OF SHELTERBELTS

Trees in the Plains region must necessarily be treated as a crop. Experience has proved that under ordinary upland plains conditions they will not survive trampling by livestock or competition by grass or weeds. Fencing and cultivation are therefore a positive necessity.

The care of shelterbelts falls into three general classifications—fence maintenance, soil cultivation, and tree culture.

Fence maintenance will consist of replacement of posts, tightening of wire, and removal of tumble weeds. The latter may so increase wind pressure on fences as to cause pulling of wire and loosening of staples; they also present a dangerous fire hazard. Current inspection will be needed to prevent livestock from trespassing. It is hoped that replacement of posts will not be necessary for many years, since creosote-treated posts or those of durable species will be used.

Cultivation is extremely important in establishing shelterbelts and serves its best purpose when done as soon after heavy summer rains as it is possible to work the soil. Cultivation aerates the soil, puts it in better condition for holding soil moisture, and removes weed competition.

The close spacing specified for the shelterbelt as a means of quickly establishing a dense overhead of foliage precludes cultivation of the interior for longer than 3 or 4 years. Under ordinary conditions, the number of cultivations should be about 4, 3, 2, and 1 for years from the first to the fourth, successively. After the third or fourth year only conifers and the outside fallow strip will have to be cultivated. The latter should be given 1 or 2 thorough cultivations each year indefinitely, to prevent the encroachment of sod and weeds.

The spring-tooth harrow and the duck-foot cultivator have long been recognized as the most desirable implements for tree culture on the plains. The spring-tooth harrow is the better of the two, since, not running on wheels, it will pass under the low-growing limbs. The common single-disk harrow is objectionable because it leaves the soil in ridges piled against the rows of trees. Tandem disk harrows remove this objectionable feature.

From Nebraska south, the common cultivating implements cannot be used in less than 10-foot spacing. Consequently, narrower implements will have to be acquired especially for the shelterbelt work instead of depending on equipment available locally on farms.

If good nursery stock is used, and if planting is followed by a season of abundant moisture, the plantation thus established will require very little, if any, subsequent pruning. Under such conditions the tree will develop one main trunk and maintain it throughout its life. If, however, inferior planting stock is used, and if as a result of dry weather or rodent injury the trees sprout from below, a considerable amount of pruning will be required to maintain the shape and appearance of the tree. In general, the rule of pruning, applying only to the interior rows of tall-growing trees, should be to maintain one main trunk with a minimum of pruning. Natural pruning will dispose of the lower limbs as the trees grow in height. The low-growing trees and shrubs should not be pruned of side branches under any circumstances. It is often desirable, however, to trim the tops of such shrubs as caragana in order to stimulate development of additional sprouts and limbs, and thus assure a tighter hedge formation.

Tree culture will include removal of diseased and dead trees, and such measures as are necessary to prevent or control insect infestations or other pests. In some cases, thinning to release suppressed growth will be needed. This phase of the work will require special attention and supervision by technically trained men.

SPECIAL PROTECTIVE MEASURES

PROTECTION AGAINST LIVESTOCK

Farm animals will have valuable shelter and protection in the lee of shelterbelts, but not within them. Livestock damage has been a principal cause of premature deterioration in many of the earlier wind breaks and shelterbelts. Protection against livestock will be provided by fencing. Adequate preservative treatment of wood posts will be provided.

PROTECTION AGAINST RODENTS2

2By F. E. Garlough, Bureau of Biological Survey.

Protection of recently established shelterbelts against rodents, particularly jack rabbits, will be a problem of the first magnitude. These rabbits often cause severe damage to young trees of certain species, such as dwarf Asiatic elm, bur oak, cottonwood, and willows, by cutting them off at the ground or snow surface. They may completely girdle trees 10 or more years of age. Such damage generally is caused in winter and early spring, when the animals' usual food supply is scarcest.

Other rodent pests to be controlled in the shelterbelt zone are cottontail rabbits, pocket gophers, various species of mice, ground squirrels, and prairie dogs.

Control measures against rodent pests, where needed, will be along the following lines:

Organizing and carrying on rabbit drives.

Trapping.

Use of repellent sprays.

Use of poison sprays and baits. (In using these, extreme care will be exercised in order that domestic animals and desirable birds shall suffer an absolute minimum of loss.)

To use the various control measures most effectively, surveys will be conducted to determine relative populations of the various species in different parts of each State. Data are also needed on the extent of daily and seasonal movement of each species, in order to determine the distance to which control should extend on each side of the planted strips. Such data can be obtained by trapping or shooting all the rodents of a given species on an area of definitely known acreage.

Research work will also be necessary to develop sprays that will be repellent to rodents and still not be injurious to the young trees.

DISEASE PREVENTION AND CONTROL3

3By Ernest Wright, associate pathologist, Bureau of Plant Industry.

Prevention or control of disease is in some cases a critical factor in the successful development of trees. The most important pathological problems that can be foreseen in the beginning of the shelterbelt project are briefly summarized.

Coniferous seed-bed diseases.—Damping-off or root rot of coniferous seedlings may be disastrous. In general, adjustment of the acidity of the seed-bed soil has proved a satisfactory means of control. Aluminum sulphate or sulphuric acid applied at the time of sowing, or sulphur applied several weeks before sowing, has been effective in increasing the soil acidity to a point unfavorable to the growth of parasitic fungi. Usually the problem of acidification must be solved independently for each nursery site.

Red cedar seedling blight.—While eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) seedlings are not seriously damaged by damping-off and root rot, they are frequently attacked by a blight caused by the fungus Phomopsis juniperovora, which commonly kills young seedlings and is generally more severe during moist seasons. In some years older trees are damaged. In its early stages the blight has been satisfactorily controlled by frequent applications of mercuric sprays. Once the blight becomes established, however, spraying has not been found so effective. Since the density of seedlings in the seed beds is an important factor in control of the blight, red cedar should not be grown at a density greater than 40 seedlings per square foot. The Phomopsis blight will probably be most severe from Nebraska southward.

Chinese elm root rot.—A rot of Ulmus pumila and U. parvifolia caused by Chalaropsis thielavioides has been found to result in considerable damage to the roots of these plants. The disease appears to originate in the seed beds and is generally intensified under storage or shipping conditions. Seedlings are the most severely damaged, although the roots of older trees are also infected and have caused some losses in field plantings. How much this root rot will influence survival in the shelterbelt plantings is at present unknown. Until further information is available as to its prevalence and its specific control, the roots of all dwarf Asiatic and Chinese elm seedlings will be dipped in a mercuric chloride solution (1 part of mercuric chloride to 500 parts of water) for 2 minutes prior to shipping the seedlings. It has been found that this treatment will hold the disease in check for approximately 10 days.

American elm wilt.—A wilt of Ulmus americana caused by a species of Cephalosporium appears to cause some damage, in Nebraska at least. Chinese elms are immune to this disease. No definite control measures are known other than the eradication of infected seedlings or trees.

Poplar canker.—A Cytospora canker holds a considerable threat to poplars throughout the shelterbelt zone. The most effective means of control is by the excision of the infected parts. If stem canker occurs on seedlings, they should be destroyed and burned as soon as possible.

Cedar apple rust.—It is well known that the so-called "cedars" (Juniperus spp.) are alternate host to the cedar apple rust. Since, however, the shelterbelts are not expected to traverse commercial apple growing territory, it does not appear justifiable to restrict the use of the junipers to any large extent, although some restriction may be necessary in a few sections where home-grown apples are of importance. The rust is already present in some parts of the region and many planted cedars will probably become infected. While they will generally not be damaged seriously by the rust, the presence of the galls does reduce the growth rate of infected trees to some extent.

It is quite clear, however, that no other alternate hosts of the cedar apple rust should be used in the shelterbelt plantings with the cedars, such as hawthorn or wild crab apple. The use of such trees in close proximity to each other would be unwise and would probably lead to a considerable reduction in the growth rates of each host and a general intensification of the rust.

Buckthorn rust.—Buckthorn is an alternate host for the crown rust of oats. Studies by plant pathologists in North Dakota and South Dakota have shown that this rust is most abundant in regions of heaviest precipitation; hence the farther east the shelterbelts are planted, the more questionable will become the use of buskthorn. The fact that oats are not grown at present in an area should not in itself remove the question concerning the use of buckthorn, since certain native grasses may also become infected and may in this way carry the rust from year to year.

Texas root rot.—That portion of the shelterbelt zone beginning about 50 miles north of the Red River and east of Jackson County, Okla., and extending thence south and west, is an area known to be sporadically infected with the Texas root rot. This rot attacks a great number of tree species and will probably cause serious losses in shelterbelt plantings unless precautions are taken. A few tree species are immune to infection, and some others are very resistant. Pending a thorough survey and mapping of the region affected, it is safer to use only immune or resistant species. Species known to be immune are hackberry, Osage-orange, and sycamore. Among resistant species are eastern red cedar and pecan, though the latter is susceptible in the seedling stage. There are in all probability many others in the immune or resistant class, but until the species situation is more fully tested out, planting in this area should proceed with caution.

The following are especially susceptible to infection and should not be used: Chinese and dwarf Asiatic elms, lilac, Russian mulberry, and Pistacia.

CONTROL OF INSECT PESTS

Among the more important insect pests that have been observed and reported in or near the shelterbelt zone are the following:

Leaf eaters: Cankerworms (Alsophila and Paleacrita), blister beetles (Meloidae), grasshoppers.

Cambium-wood insects: Locust borer (Cyllene robiniae), carpenter moth (Prionoxystus robiniae).

Sap-sucking insects: Aphids (Aphididae), cicada (Tibicina septendecim), scale (Coccidae).

Meristem insects of terminal parts: Pine tip moths (Rhyacionia).

Meristem insects feeding on root: White grubs (Phyllophaga).

Meristem insects of cambium region: Flathead borers (Buprestidae), roundhead borers (Cerambycidae), various bark beetles (Scolytidae).

The most serious problems will, as far as is known, be encountered with borers and with certain species which defoliate the trees. Control of the former will necessarily be accomplished mostly by silvicultural measures. The defoliators can be controlled by sprays and poison bait.

As shelterbelt planting advances there will be definite need of guidance by entomologists in determining other species of insect pests present in given areas, the magnitude and stage of infestation and practical control measures to be used. A thorough preliminary survey should be conducted to determine more exactly the present status of the insect problem.

Among measures that offer promise in the control of various insects are the following, some of which are also of value in controlling or minimizing possible damage from diseases:

Close inspection of all nursery stock.

Proper preparation of the planting site and cultivation of the young stand. This will give the trees a vigorous start and insure a larger measure of resistance to insect pests.

Use of a wide variety of species in each shelterbelt. Strips should ordinarily consist of from 3 to 8 species of trees. As already stated, ordinarily no one species should comprise more than 30 to 50 percent of the total number of trees in the shelterbelt.

Sparing use or entire elimination of certain species in planting areas where an insect pest is in an epidemic stage. Green ash, for example, shows severe damage from the carpenter worm in parts of South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas.

Selection of species that will grow most vigorously on a given planting site or soil type. It has been observed that black locust planted on dry upland sites in western Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and in the Texas Panhandle, is invariably severely damaged and often killed by the locust borer (Cyllene robiniae). When planted in low, moist sites, as along stream courses, gullies, and areas of shallow water table, it is much more vigorous and is less subject to borer attack, and the trees which are infested recover much more quickly.

Close spacing.—Less damage will occur from many insect infestations if a dense crown canopy excludes direct sunlight.

Periodic inspection of windbreaks, to detect sporadic infestations; taking the proper steps in control by use of sprays and poisons, or removing and burning infested material.

Introduction of parasites which are known to keep certain insects in check.

Encouragement of insectivorous birds.—The shelterbelts themselves, by providing nesting places, protection, and food, will unquestionably have a favorable influence on the population of insectivorous birds. Feeding of birds during severe winter weather can be resorted to.

Control of fire and grazing.—Since both fire and grazing weaken the resistance of trees, careful control should be maintained to prevent injury to the shelterbelt from these causes.

COSTS OF ESTABLISHING SHELTERBELTS

The cost of planting will vary widely according to the type of planting and according to local conditions existing at the time and place of planting. Costs will, further, be affected by conditions surrounding the production of nursery stock. Many new elements must be considered, concerning which there is relatively little exact information, such as land leases, fence construction, and various forms of protection. In general, the cost of field shelterbelt planting will be considerably higher than for either farmstead or block planting. Considering all three types, it is estimated that the average cost will be $30 per acre, including the production of nursery stock and the care of plantations, especially the field shelterbelts, for a period of 5 years after planting.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

shelterbelt/sec4.htm Last Updated: 08-Jul-2011 |