|

POSSIBILITIES OF SHELTERBELT PLANTING IN THE PLAINS REGION

|

|

Section 7.—A SURVEY OF PAST PLANTINGS6

6This section is based on field data collected by parties under the direction of J. F. Kaylor, C. C. Starring, and C. P. Ditman, of the Lake States Forest Experiment Station, Forest Service.

CONTENTS

General description of plantings

Planted area in States and counties; average heights and percentage of survival

Northern Great Plains Field Station

Analysis of present situation

Drought

Late frosts

Ownership of land

Selection of planting site

Selection of species and seed source

Method of planting

Spacing of trees

Cultivation

Protection from livestock

Fire

Conclusion

In order to get a definite perspective of the possibilities of tree planting in the prairie-plains region, a study was made of the earlier plantations, particularly as regards the causes which contributed to their success or failure. Such a study should reinforce the scientific appraisal of the shelterbelt problem and give a practical view of the pitfalls which organized forestry proposes to avoid in solving it.

The study, requiring a rapid reconnaissance of existing plantations in a wide territory within which the shelterbelt zone was to be marked out, was conducted in the fall of 1934. Plantings in the region have been numerous in years past, and the survey was intended primarily as a check, under increased severity of the drought, of conditions already well known and studied. The results of a similar but more intensive investigation in North Dakota, recently published,7 furnish much additional information that is applicable to the northern part of the shelterbelt zone in general.

7SCHOLZ, H. F. CAUSES OF DECADENCE IN THE OLD GROVES OF NORTH DAKOTA. U. S. Dept. Agr. Circ. 344, 37 pp., illus. 1935.

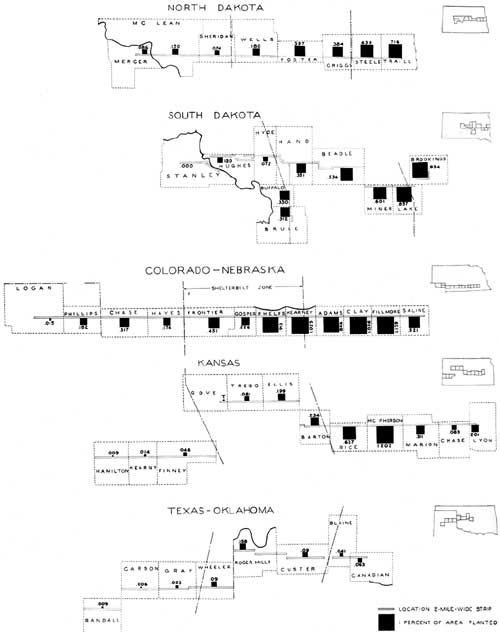

In the short time available for this survey, it was of course impossible to examine all the plantations within the general region. In order to secure a representative sample, an east-west line through a part of each State was located on the basis of topography, soils, types of agriculture, and the amount of planting done in the past. This line was considered to be the center of a 2-mile-wide strip, within which observations were made of plantings (about 1,000 in all) of trees more than 10 years old. Certain deviations were made where the line paralleled the course of streams and where it traversed land devoted more to grazing than to crop production. The line also avoided all improved highways, because farm improvements, including windbreaks, are often better than the average along such thoroughfares. Figure 11 shows the location of the 2-mile-wide strip in each county of the six States in which the shelterbelt zone is located.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF PLANTINGS

In most cases the appearance of the shelterbelts reflected the hard conditions through which they had come, not only as a result of poor adaptation to climate, but also as a result of economic hardships affecting their ownership, management, and care. On the other hand, examples of healthy survival under difficulties were noted, and in the few cases where careful adaptation and management were controlling factors, the condition of the shelterbelts was on the whole satisfactory (fig. 10). The very promising situation existing at Mandan, N. Dak., a field station of the Bureau of Plant Industry, is noted under a separate heading below.

|

| FIGURE 10.—A, Farmstead near Madison, S. Dak., vastly improved by planting of hardwoods and conifers. Shelterbelts around the farmhouse protect buildings and livestock from winter's icy blasts (F298777). B, Cottonwoods make excellent growth in low areas; scene 14 miles east of Hoxie, Kans. Such protective forest strips add beauty to the landscape as well as value to the farm property (F296046). (See text p. 39). |

Two types of relatively recently planted shelterbelts were observed. In the Dakotas they often consist of belts five or six rows in width and usually located on the north and west sides of buildings. The other type is planted in two rows so as to create a snow trap. The two parallel rows of trees are separated by a space at least 100 feet wide which is sometimes occupied by an orchard or a garden plot.

In Oklahoma, few plantations are more than three rows wide, and in Texas the plantings often consist of only a single row. In general, the width of the shelterbelts has been too small to insure a favorable forest-cover condition.

One of the best features of the older tree claims (plantings under the terms of land settlement laid down in the Timber Culture Act of 1873) is that they usually have enough width to be in some degree effective in shading the ground and getting a forest-cover condition. In the planting of tree claims to obtain title to land, some farmers made a real effort to follow the letter of the law, and as a result there can be seen in the Great Plains region a considerable number of groves over 40 years of age which are still in good condition. These are usually about 10 acres in size, and their dimensions are 10 by 160 or 20 by 80 rods. They are invariably along section or quarter-section lines.

Such tree claims are still quite common in the Dakotas, Nebraska, and Kansas. They are conspicuous by their absence in Texas and Oklahoma. The latter State was admitted to the Union after all Federal legislation had been abolished which made possible the settlement and filing on land through the medium of tree planting. In Texas no tree-planting entries were possible because there was formerly no public domain (Federally owned land) in that State.

PLANTED AREA IN STATES AND COUNTIES; AVERAGE HEIGHTS AND PERCENTAGE OF SURVIVAL

General physical and climatic conditions were found to be largely accountable for the distribution of shelterbelts over the area. In the northern part, where winters are severe, a great many groves have been planted for the protection of homes as well as of livestock against snow and cold winds. In North Dakota the area occupied by planted groves was found to vary from 4.58 acres per square mile in eastern locations favorable for tree growth to 0.48 acre in the western part of the State where conditions are the most difficult. In all areas in which tree planting can be done with reasonable expectation of success, plantings average 2.56 acres per square mile. In South Dakota and Nebraska, where winters are also severe, the proportion of planted area is considerably larger.

In Kansas the proportion falls to 2.3 acres per square mile in the part best suited to tree growth, and to 0.31 acre per square mile in difficult parts. In Oklahoma and Texas, where winters are milder, settlers have not experienced the absolute necessity for protection that exists in the North, and the proportion of area planted for protection decreases toward the vanishing point. Table 8 shows the estimated proportion of the area of each State devoted to shelterbelts and similar plantings and the proportion of area so planted (by private effort) within the shelterbelt zone, as well as the approximate acreage planted in the zone. Figure 11 shows the estimated proportion of planted area in each county surveyed.

TABLE 8.—Areas devoted to protective planting1

| State | Proportion of area in groves |

Area of groves in shelterbelt zone | |

| Entire State1 | Shelterbelt zone | ||

| Percent | Percent | Acres | |

| North Dakota | 0.250 | 0.303 | 38,800 |

| South Dakota | .325 | .560 | 71,680 |

| Nebraska | .533 | .609 | 77,952 |

| Kansas | .300 | .148 | 18,944 |

| Oklahoma-Texas | (2 | .114 | 21,900 |

| Total | .347 | 229,276 | |

1 Estimated from survey figures. 2 Sample too small to give reasonable estimate. | |||

|

| FIGURE 11.—Location of survey strips in States of the shelterbelt zone, together with percentages of area in forest plantings in counties sampled. (click on image for a PDF version) |

The percentage survival of trees in plantings is shown according to States in table 9. This survival figure is the proportion of living trees to the total number of trees found in the groves when examined, and not on the number originally planted. The groves were divided into two groups, those under and those over 30 years of age. In most cases survival was better in the younger groves, a fact due to the longer time for the accumulation of dead trees in the older plantations and the greater experience behind the planting of the younger groves.

TABLE 9.—Average survival of planted trees in States of the shelterbelt zone

| State | Average survival of trees | ||

| In groves under 30 years old | In groves over 30 years old |

In all groves | |

| Percent | Percent | Percent | |

| North Dakota | 41.8 | 44.2 | 43.1 |

| South Dakota | 43.6 | 25.7 | 31.8 |

| Nebraska | 32.7 | 30.4 | 17.8 |

| Oklahoma-Texas | 25.9 | 34.2 | 28.4 |

| Average | 36.8 | 23.8 | 28.7 |

Among broad-leaved species the range of survival was, roughly, from 21 to 50 percent in young groves and from 17-1/2 to 30 percent in groves of all ages, with green ash taking the lead in the one case and American elm leading by a slight margin in the other. Among the conifers eastern red cedar far exceeds the broad-leaved group in its survival showing, which averaged 93.2 percent in all plantings examined. While the number of groves in which it appeared was relatively small, its rugged resistance recommends it for much wider use. Survivals of the more prevalent species, not subdivided as to State, are shown in table 10.

TABLE 10—Average survival of principal species examined in plantings

| Species | Groves in which occurring |

Average survival | ||

| In groves under 30 years old |

In groves over 30 years old |

In all groves | ||

| Number | Percent | Percent | Percent | |

| Green ash | 635 | 48.5 | 20.4 | 20.5 |

| Cottonwood | 459 | 34.0 | 24.1 | 27.1 |

| Boxelder | 456 | it.1 | 20.2 | 25.2 |

| Mulberry | 403 | 25.6 | 12.9 | 17.4 |

| American elm | 223 | 38.0 | 20.1 | 30.2 |

| Black locust | 208 | 20.8 | 23.3 | 21.1 |

| Catalpa | 127 | 26.6 | 9.7 | 20.1 |

| Eastern red cedar | 93 | 94.9 | 92.4 | 93.2 |

The average heights of trees over 30 years in age of certain key species—those which usually give character to the groves—are as follows: Cottonwood, 50 feet; American elm, 27 feet; green ash, 26 feet; black locust, 26 feet; and eastern red cedar, 17 feet. These values represent a general average for the region, and will be markedly exceeded in some groves and not attained in others at the same age.

NORTHERN GREAT PLAINS FIELD STATION

The Northern Great Plains Field Station of the Bureau of Plant Industry, at Mandan, N. Dak., affords an excellent example of what can be done in the planting of shelterbelts. From 1916 to 1933 it has been instrumental in establishing on a cooperative basis with farmers in the western part of the Dakotas and in eastern Montana and Wyoming more than 2,700 demonstration shelterbelts. Despite the fact that this area lies west of the shelterbelt zone and has less favorable growing conditions, average survival for these plantings is over 70 percent.

In addition, the station laid out on its grounds at Mandan, from 1914 to 1920, approximately 100 test blocks of different types involving variations in species, spacing, cultivation, pruning, and mulching. These experimental plantings have been maintained under dry-land agricultural conditions and have demonstrated the value of reasonably close spacing. Figures 12 and 13 whow two very fine test blocks.

|

| FIGURE 12.—Test block of ponderosa pine, Northern Great Plains Field Station, Mandan, N. Dak. (F295452) |

|

| FIGURE 13.—Test block of blue spruce, Northern Great Plains Field Station, Mandan, N. Dak. (F295450) |

ANALYSIS OF PRESENT SITUATION

If a serious picture of the condition of privately owned and planted shelterbelts has been drawn, it is mainly to focus attention on the factors that have brought the condition about, so that they may be allowed for or avoided in planned and organized action. They lie in the spheres of climate, occupancy, and technical management, and will be considered in order.

DROUGHT

Drought is undoubtedly of primary importance as a factor of damage and also as a test of the ability of individual species planted in shelterbelts to survive. During and after 1931, moisture conditions for plant life in the prairie-plains region became increasingly acute, and the summer of 1934 provided a devastating climax to the dry period.

Although considerable losses had been reported before 1931, the majority of the shelterbelts seemed to have held their own fairly well despite moisture shortage, sleet, rodents, grazing, and insects. But the parching winds and searing temperatures of the last 3 years proved to be more than many of the trees could withstand. In the Dakotas a feature of the general damage was that caused by the death of crown tips. A comparison of the survival figures obtained in the 1931 survey of North Dakota with the 1934 figures affords an estimate of the losses by drought during the interval. While the two surveys did not cover exactly the same area, the figures should be to some extent comparable. In the 1931 survey 293 plantings showed an average survival of 73.7 per cent, whereas the survival for the groves examined in 1934 in North Dakota was only 43.1 percent. South of the Dakotas an even heavier toll of trees was taken by heat and drought. It should be remarked, however, that throughout the region the worst damage occurred where the soil was bare and packed hard by grazing stock. This compacting of the soil prevented the proper penetration of what little precipitation fell.

LATE FROSTS

Low temperatures as well as high must be taken into account when planning shelterbelt plantings. Late spring frosts are apt to injure undeveloped parts in lateral and terminal growing regions. Damage of this sort was caused in at least one instance encountered on the survey by a hard frost occurring in early April, which killed growing tips of mulberry, black locust, and honeylocust; the mulberry and black locust showed better recovery than the honeylocust.

Sleet, hail, and winds of cyclonic force are other climatic factors which have caused and will cause damage in the shelterbelt area and elsewhere. The best of planning can only allow for their occurrence, not try to forestall their effects.

OWNERSHIP OF LAND

Frequent change of ownership has militated generally against the proper care and upkeep of shelterbelts. Among the farms covered in the survey it is only the rare exception that has been in the continuous ownership of one man or his family. Often, where trees were planted and given good care originally, the sale of the farm meant a change in sentiment as well as in the person of the owner. The trees might be utilized for firewood or the grove turned into a stock pasture. Trees on farms operated by tenants are even more subject to bad treatment or neglect, through the indifference of the more or less transient occupants.

In some cases the national origin of settlers has been noted as a factor in the planting and care of shelterbelts. In sections originally settled by Germans and Scandinavians the greatest and most successful efforts in this direction were apparent.

A fortunate feature of tree planting under public auspices is that the undertaking carries at least the promise of permanent tenure and of uniform, continuing policy.

SELECTION OF PLANTING SITE

The first act of the homesteader was to locate a site for his house. Often the principal aim was to select a spot which afforded a view of the entire farm or ranch. After the house had been built, the need for protecting it from snow and wind became apparent, and if trees were planted they had to be planted where they would serve the need. Consequently, many groves and windbreaks were planted on soils which were either prohibitive or extremely difficult, for tree growth. Other factors were also unfavorable on many sites. Often groves were situated on steep slopes where run-off of precipitation was rapid and where the trees were unduly exposed to the wind. In the relatively few cases in which the buildings were located in sheltered sites, the trees planted for protection survived well and proved to be a sound investment of the money and time required to establish them.

SELECTION OF SPECIES AND SEED SOURCE

Selection of species used for planting has decided the success or failure of the planting effort in cases without number. The earlier plantations show very little evidence of forethought in the selection of species. Apparently the species for planting were usually selected more as a matter of personal fancy than of adaptation to conditions. Newly introduced, fast-growing species were evidently in greater favor than the more drought-resistant, slower-growing native trees.

In many instances stock was purchased from nurseries at a considerable distance where conditions were very unlike those of the locality in which planting was to be done. Often the seed from which the stock was grown was not of the same climatic region.

Naturally, such a hit-or-miss method resulted in the planting of a class of stock and of many species entirely unsuited to the region of prairie climate. The only existing evidence of many thousands of dollars spent in trying out these unadapted species and types is a disposition on the part of many farmers to consider tree planting a useless waste of money and effort.

Later, in communities where an active county agricultural agent had secured the cooperation of Federal and State forestry agencies, the composition of the groves was better. Demonstration plantings of suitable composition served to stimulate interest in local species. Shrubs and low-growing trees, however, were very seldom used, as their value for flanking taller growing shelterbelt trees has been realized only lately.

Choice of species in the future should be guided by the experience and advice of testing stations which have made a special study of species adaptation to shelterbelt conditions.

METHOD OF PLANTING

In some cases the experience of the farmers in regard to living plants guided them in properly planting and caring for the young trees. Usually, however, the small seedlings, when not supplied by a nursery, were pulled up and carried without any covering to the planting site. Often the plants were subjected to excessive drying, as when furrows had been opened long in advance of planting. Sometimes the seedlings were laid at an angle in a shallow furrow and covered by plowing a ridge of soil against them.

Naturally, such methods were not conducive to survival, and many of the trees succumbed early. When more painstaking methods were used the success was markedly greater. In the matter of planting, as in species selection, the cooperation of Federal and State agencies with the farmer through the county agent has been invaluable.

SPACING OF TREES

In the first plantations the density of planting was dictated by section 2 of the Timber Culture Act as amended in 1878, which required the planting of 2,700 trees per acre, equivalent to a spacing of about 4 by 4 feet. Frequent cultivations with a breaking plow destroyed large numbers of trees by exposing their roots. Many trees died from other causes, and the resultant spacing in the older plantings is now approximately 8 by 8 feet.

Where thinning was not practiced, some of the trees originally planted succumbed from crowding, as might be expected. This natural process has caused many planters of the present generation to believe that the original spacing was too close, and in recent plantings they have adopted a spacing of 8 by 8 feet. The change, which appears to be mainly an attempt to eliminate the need for artificial thinnings, is to be regretted. In widely spaced plantations the freer sweep of wind greatly reduces the opportunity for the accumulation of leaf litter and also increases the evaporation rate. Moreover, too wide spacing of trees permits too much sunlight to reach the soil and favors the increase of insect pests. The protective effect of the shelterbelt is decreased and its primary purpose thus in a measure defeated.

In the closely planted groves natural thinnning alone is often sufficient to maintain a fairly normal growth rate, The earlier dense plantings that were observed showed a markedly good survival, fair forest-floor conditions where grazing had not been allowed, and a general tendency to retain a spacing closer than 12 by 12 feet at 50 or more years of age. The recent more widely spaced plantings show considerable loss through sun scald.

CULTIVATION

Cultivation is one of the most important factors in establishing shelterbelts. Many of the older plantings in the Plains region were given only 1 or 2 years of cultivation and then left to shift for themselves. Consequently competing weeds and grasses obtained an early foothold and aided very materially in causing poor growth or early death of the groves.

PROTECTION FROM LIVESTOCK

Unrestricted grazing was found to be one of the commonest causes of excessive mortality in both old and young shelterbelts. In some cases the groves were fenced at the time of establishment and the fences kept in good repair. In most of them, however, there has been grazing at some time or other during the life of the trees. Many of the groves have been open to the depredations and trampling of stock from the time they were planted, although others have been kept free of livestock until the past few years when scarcity of regular feed and the necessity for shelter from the terrible heat forced the farmer to open his groves to the stock. Many of the fences have been allowed to go to pieces because of the farmer's preoccupation with crop production. But whatever explanation lies behind the fact of stock grazing, the effect remains the same, differing from farm to farm in degree only.

When cattle, sheep, hogs, horses, or even fowls are permitted to forage and bed in the groves, the soil is compacted in greater or less degree. The roots of the trees are exposed by the cutting and trampling action of the animals' hoofs. This leads eventually to the death of the trees, when hot winds or direct sunlight reach the exposed roots. In addition to the direct effect on the roots, compaction of the soil creates unfavorable conditions for moisture absorption. Sprouts, seedlings, and young trees, the lower branches of older trees, and all the smaller plants are ordinarily consumed by the grazing stock. Thus the accumulation of a normal leaf litter and moisture conserving mulch becomes impossible.

Groves were observed where trees of small diameter and up to 15 or 20 feet tall had been "ridden down" by cattle in their efforts to reach young, tender branches and leaves. Places were found where sheep had stood on their hind legs and ripped off branches and bark. Severe damage by the scratching and roosting of large flocks of poultry was also plainly in evidence.

The destructive effects of grazing in farm woodlots have been studied and presented in a number of publications. Practically all of them point out that grazing causes lowered soil porosity, greater evaporation from the soil surface, continued loss of the normal leaf litter. complete lack of reproduction, and mechanical injury to the trees and their roots.

In Griggs County, N. Dak., an ungrazed plantation of green ash showed a survival of 70 percent, whereas in a comparable plantation which was moderately grazed the survival was reduced to 30 percent. Excellent forest-floor conditions existed in the ungrazed grove; there was a heavy layer of litter and leaf mold forming a water-holding blanket near the surface of the soil. Ground cover of young growth and shrubs aided in the collection and retention of snow. In contrast to this favorable condition, the grazed area showed many bare spots and openings without leaf litter or reproduction and was covered with a mat of sod competing with the trees.

Figure 14 shows the remnants of a grove which has been heavily pastured for many years. Only the trees near the road have been able to survive. Figure 15 shows a grove in which grazing has been permitted for only a short time. The differences are obvious. The inevitable conclusion from first-hand observations over then entire area is that grazing in areas planted to trees, especially on heavy soils, must be reduced to a minimum or entirely prohibited if the trees are to continue to grow and maintain themselves.

|

| FIGURE 14.—Remnant of a fairly extensive planting of green ash near Oakley, Kans. Only the trees growing next to the road ditch have survived the soil packing and other results of years of pasturing. (F296055) |

|

| FIGURE 15.—Excellent grove of green ash near Redfield, S. Dak., at about the center of the shelterbelt zone. The floor conditions here, unaffected by grazing until recently, illustrate conditions which are absolutely vital to the survival of plantations through drought periods. Original spacing, 3 by 3 feet; present spacing averages 6 by 6 feet at about 40 years of age. (F289982) |

FIRE

Fire is still another factor which has a detrimental effect on tree growth in the shelterbelt zone. Residents of many communities recalled destructive fires which swept over the Plains in earlier times, and these are generally conceded to be accountable in part for the sparsity of natural tree growth in the region. In more recent times, fires have been started intentionally and often for the express purpose of removing tree growth which might be interfering with the owner's urge to put ever acre into crop production. Careless burning of rush and weeds in garden plots has often injured or killed trees growing in the immediate vicinity.

Fire must be kept away from planted groves if they are to succeed.

CONCLUSION

In recent years plantings have improved considerably in species, composition, and the care they have received, owing mainly to the guidance and cooperation received by farmers from State and Federal agencies.

Summing up the results of shelter-belt plantings on the basis of the recent survey, some 230,000 acres appear to have been more or less successfully planted in the shelterbelt zone in the past 50 years. This figure does not include former plantings of which there is no present visible evidence. The average survival in the existing plantings is slightly less than 30 percent. Considering the poor care which characterized the establishment of some of these windbreaks, particularly the older ones, they have fared reasonably well. There are numerous tree claims from 40 to 50 years old over the entire shelterbelt zone from which much valuable information has been obtained as to the ultimate height and average age that individual species can be expected to attain under different conditions.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

shelterbelt/sec7.htm Last Updated: 08-Jul-2011 |