|

POSSIBILITIES OF SHELTERBELT PLANTING IN THE PLAINS REGION

|

|

Section 8.—A REVIEW OF EARLY TREE-PLANTING ACTIVITIES IN THE PLAINS REGION

By JOHN H. HATTON, inspector, Plains Shelterbelt Project, Forest Service

CONTENTS

Federal efforts to encourage tree planting

Arbor Day

State efforts

North Dakota

South Dakota

Nebraska

Kansas

Oklahoma

Texas

Records of western exploration, beginning with the expedition of Lewis and Clark, contain detailed mention of tree species growing along the watercourses of the Plains which tallies in essential respects with the taxonomy of the region as it exists today. But the uplands of the Plains country have from prehistoric times been an essentially grassland rather than forest country. Currently accepted estimates place the total originally forested area of the Dakotas, Nebraska, and Kansas at about 3-2/3 million acres, out of a total land area in those States of nearly 200 million acres.

Even before settlement by the whites, such wooded areas as were present had been subject to man-caused injury. The native timber had influenced the habitat of various early Indian tribes, who frequently set fires in order to deter the ingress of other tribes to favored hunting grounds.

When the white settlers came into this region, they first took up such lands as had accessible timber. With their advent came also extensive cattle grazing and more frequent prairie fires, both of which made further encroachments upon the native tree growth. The use of wood for fuel by river boats made another drain upon the natural wood supply, particularly cottonwood. Along the Missouri River extensive woodyards were established in the early days. Beginning in 1850, when the first river boat was put into operation on the Red River (of the North), a similar course of exploitation of native timber followed.

"All the native timber" in Nebraska was cut, according to a report in 1878, at the time of the building of the Union Pacific Railway. which was completed in 1869. The reference, no doubt, is to trees of usable size growing within a reasonable distance of the Platte River Valley.

Where destructive factors were eliminated, native timber reclaimed sections where it had been destroyed and, according to some opinion, even extended into other districts where it had not grown for centuries. But prairie fires continued to be a menace in some places both to native timber and planted groves. Before lands were generally plowed, prairie fires having wide scope frequently got beyond control and swept into or through planted groves, destroying or seriously impairing the growth of several years. Shelterbelt surveys made in 1934 and 1935 have brought to light the history of many plantings formerly existent but now completely effaced.

|

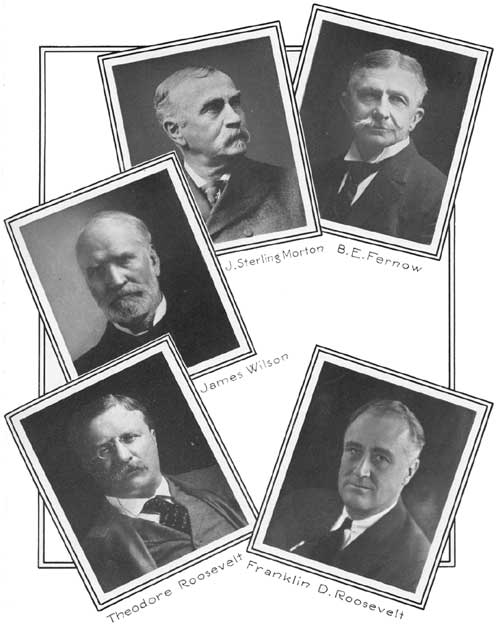

| FIGURE 16.—Prominent figures in the development of forestry in the Great Plains region. |

FEDERAL EFFORTS TO ENCOURAGE TREE PLANTING

As early as 1866, Joseph S. Wilson, Commissioner of the General Land Office, petitioned Congress to afforest the Plains in part. His message to Congress read:

If one-third the surface of the Great Plains were covered with forest, there is every reason to believe the climate would be greatly improved, the value of the whole area as a grazing country wonderfully enhanced, the greater portion of the soil would be susceptible of a high degree of cultivation.

On March 3, 1873, Congress passed the Timber Culture Act. This has been the most conspicuous act in tree-planting history, either Federal or State. It provided for planting 40 acres on a timber-culture entry of one-quarter section, with trees not more than 12 feet apart each way. The act was amended in 1874 to permit entry of smaller tracts and requiring only a proportionate amount (one-fourth) of tree planting according to the acreage filed on. It was amended again in 1876, still retaining the 12-foot spacing, but permitting planting in four separate tracts and requiring replanting within a year of any trees, cuttings, or seeds which did not germinate or grow, or which were destroyed by grasshoppers.

A further amendment of the act in 1878 required that not less than 2,700 trees per acre be planted, which is equivalent to the requirement of 4- by 4-foot spacings. Provision was also made in this amendment that final certificates would be issued on a showing of 675 living and thrifty trees to each acre. Because the larger settlement booms occurred in the late seventies and the early eighties, most of the timber-entry planting was done under the 1878 provisions.

The Homestead Act went into effect May 20, 1862. Between that time and the passage of the Timber Culture Act a considerable number of settlers who came to the Plains States to establish permanent farm homes sought to improve their surroundings by planting groves and shelterbelts, and there are records of remarkably successful attempts at tree culture in some of the early-settled States. Tree planting on what might be termed a general scale, however, did not begin until shortly before the passage of the Timber Culture Act. While this act, repealed in 1891, cannot be said to have been generally successful, it did have the effect of further directing popular thought to tree culture as an important complement to Plains settlement. Commercial nurseries gradually adjusted themselves to provide additional and proper planting stock, and tree-planting thought pervaded the atmosphere more generally.

The Nebraska National Forest established by proclamation on April 16, 1902. by President Theodore Roosevelt, constitutes the largest demonstration of sand-hill planting of conifers in the western country. The project was conceived through the success of a plantation of conifers established by the former Division of Forestry of the Department of Agriculture, in Holt County, Nebr., which is in the present shelterbelt zone. In 1891 some 20,000 seedlings were shipped in and planted on typical sand hills according to plans proposed by the then chief of the Division, B. E. Fernow. The species were ponderosa pine, jack pine, Scotch pine, and Austrian pine. Black locust, box elder, hackberry, and black cherry were used as nurse trees.

The results of this planting led to a field examination of all the western Nebraska sand-hill area in 1901 and of the sand hills of southwestern Kansas in 1902. An area of 302,387 acres in Kansas was also proclaimed a national forest, the initial part of it in 1903, but for a number of reasons was discontinued as a national-forest project in 1915.

About 12,000 acres of coniferous forests have since been successfully established on the Nebraska area. A nursery8 in the forest with an annual capacity of 2,500,000 trees has furnished the stock for a planting program now going forward on a scale of 1,000 to 1,200 acres annually. The capacity of the nursery is being greatly enlarged and its distribution and services extended to other projects.

8At Halsey, Nebr., named the Bessey Nursery, in honor of the late Charmes E. Bessey, of the University of Nebraska, through whose urging the initial steps were taken toward establishing the Nebraska National Forest.

The annual appropriation act for the Department of Agriculture passed on March 4, 1911, provided for furnishing trees from the nursery free of charge to settlers in the Sixth Congressional District of Nebraska, for which special homesteading privileges had been authorized by the Kincaid Act of April 28, 1904. Recently, the sixth congressional district was absorbed by the fifth, but the area covered by the original act remains the same. The provisions and purposes of the Kincaid Act have been largely absorbed by the Clarke-McNary Act.

In the 1913 appropriations for the Department of Agriculture, Congress included permission for the establishment by the Bureau of Plant Industry of the Northern Great Plains Field Station at Mandan, N. Dak., across the Missouri River from Bismarck, part of its activity to be the "growing, distributing, and experimenting with trees suitable to that region." Since the beginning of distribution in 1916, nearly 6,000,000 trees have been supplied to farms in parts of Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota and South Dakota. The information resulting from these plantings will probably make the largest single contribution to the shelterbelt project because of the authentic records that have been kept on the behavior and successes of different species and methods of culture under different conditions, both at the station and in widely scattered field planting. This service is being supplemented by the Southern Great Plains Field Station at Woodward, Okla., and the Horticultural (or central Great Plains) Field Station at Cheyenne, Wyo.

On June 7, 1924, a milestone was erected in American forestry legislation. This was the passage of the Clarke-McNary Act, which provides for Federal and State cooperation with landowners in (1) the protection of forest land from fire, (2) the study of tax laws and the devising of tax laws designed to promote forest conservation, (3) the procurement and distribution of forest-tree seed and planting stock, (4) the establishing and renewing of woodlots, shelterbelts, and other forms of forest growth, and (5) the development and improvement of timbered and denuded forest land through acquisition and control by the Federal Government. Section 4 covers the distribution of seed and planting stock and has had a marked effect on the planting of shelterbelts and woodlots. For the distribution to be operative in any State it is required that the State make provisions to cooperate with the Government either through legislation or by designating an appropriate State department, such as the extension service, State forester's office, or conservation department, to perform the work under Federal inspection.

Results under the Federal acts have varied. Notwithstanding the strict provisions of the Timber Culture Act, it is well known that there were many cases of insincere or even fraudulent attempts at growing trees with the intent of getting title to free land; and it may be said, in general, that the existing stand of planted groves in the entire shelterbelt zone, estimated at 230,000 acres on the basis of recent observations, amounts to but a minute fraction of the 52,000,000 acres of the zone lying in the region subject to entry under the Timber Culture Act—a much smaller fraction than the extensive planting requirements of the law might have led one to expect.

But, in thousands of cases, the attempt to establish groves and shelterbelts was earnest, and repeated efforts were made until proper species and methods of culture were worked out. A large proportion of the settlers wanted trees, but the difficulties of growing them were many. Often nursery stock was bought comprising species that were neither hardy nor at all adaptable. The farmers in many cases had to profit by their own experience as tree growers, and valuable time was lost in the process. Since those earlier years, much attention has been given the subject of hardiness of species, and the pitfalls awaiting the early planters in this respect can now be avoided.

In many areas, where the planting spirit prevailed, groves spraining up and dotted the landscape, and many of them, living and thriving after 50 or 60 years, are in evidence today. These woodland monuments erected by the early settlers show the great possibilities that lie ahead of large-scale tree culture under a definite and sustained program of soil preparation, proper selection of species, provisions to hold the snows, protection of the stand, and sustained cultivation and care until forest conditions shall have become established.

ARBOR DAY

Arbor Day originated in Nebraska and was first observed April 10, 1872. Since then it has come to have national and international significance. The plan was conceived and the name Arbor Day proposed by J. Sterling Morton, of Nebraska City, who was then a member of the State Board of Agriculture and later the third United States Secretary of Agriculture. According to Morton's History of Nebraska, a million trees were planted in Nebraska on that first Arbor Day. One man planted 10,000 cottonwood, soft maple, Lombardy poplar, boxelder, and yellow willow trees on his farm south of Lincoln.

On March 31, 1874, Governor Furnas, who himself had been an ardent supporter of afforestation, issued a proclamation designating Wednesday, April 8, as Arbor Day. This was the first official recognition of the event.

Each State now observes Arbor Day by Governor's proclamation or by law. It has become a school festival, which is observed not only in the United States but also far beyond its borders. Canada, Spain, Hawaii, Great Britain, Australia, the British West Indies, South Africa, New Zealand, France, Norway, Russia, Japan, and China, as well as the United States possessions now observe the occasion.

STATE EFFORTS

Each of the States through which the shelterbelt zone passes has encouraged tree planting by various means, both before and since the passage of the Timber Culture Act. Intelligent popular interest has also been wide-spread. Outstanding features of the movement will be outlined below under headings of the respective States.

NORTH DAKOTA

The area in native timber in North Dakota is said to be smaller than that in any other State in the Union.

There was little tree-planting activity in the State prior to the Timber Culture Act of 1873. In that year the Northern Pacific Railway was built to the Missouri River at Bismarck, and it was not until afterward that the influx of settlers reached the part of the State west of the Red River Valley.

North Dakota has a State forester designated by law. It also has a forest nursery established in 1913 at the School of Forestry at Bottineau. Both hardwood and coniferous trees are grown for distribution throughout the State, and work has been carried on in every county. The State has qualified for cooperation under the Clarke-McNary law. In addition, the State at one time offered a small bonus for planting and cultivating trees. Largely as a result of these activities, a distant horizon view now shows almost continuous plantations in some of the earlier-settled parts. Previous mention has been made of the important work of the Bureau of Plant Industry at the Mandan station.

Of special interest in North Dakota has been the tree-planting activity of the Great Northern Railway to prevent drifting of snow on the right-of-way. The work began in 1905. At the close of the season of 1909, 96,230 trees had been planted along 26.35 miles of main track between Grand Forks and Williston, at which time the percentage of trees living was reported as 81.5, as shown in the following figures, listed according to species and numbers planted:

| Percentage living | |

| Ash (25,436) | 79.6 |

| Elm (18,371) | 87.5 |

| Southern cottonwood (16,684) | 74.3 |

| White willow (12,815) | 76.3 |

| Laurel willow (2,983) | 86.7 |

| Niobe willow (8,000) | 85.0 |

| Silver maple (3,697) | 89.0 |

| Silver poplar (2,000) | 85.0 |

| Boxelder (5,729) | 89.3 |

| Cottonwood (365) | 86.6 |

| Gray willow (150) | 85.4 |

| All species (96,230) | 81.5 |

Detailed data on these plantings for years since 1909 are not at hand. Recent observations indicate however, that the plantings for the most part are serving their purpose well.

According to estimates of F. E. Cobb, State shelterbelt director, there were planted in the North Dakota portion of the shelterbelt zone in the 10 or 12 years just prior to 1935 approximately 8 million trees, of which at least 60 percent have survived the drought and are growing.

SOUTH DAKOTA

In South Dakota a large part of land settlement occurred from 1870 to 1890, and records of tree planting prior to the Timber Culture Act are meager or of relatively small importance. Many plantings, mostly east of the Missouri River and within the central lowlands, were made under the terms of the Timber Culture Act, and many are still in evidence.

The State College of Agriculture at Brookings made extensive plantings in typical prairie sections on the east border of the State in 1885 and 1886. The trees were spaced 4 feet each way, too closely to grow to maturity without thinning. They suffered somewhat during the drought of 1893-94. In its more than 40 years of activity, the horticulture department of the State college at Brookings has made large contributions to successful tree culture by disseminating information on hardy species and methods of culture. The published reports of the South Dakota Horticultural Society record much of this information.

Forestry activities are, on the whole, of minor development in the State. No State nurseries exist. However, a State forest was created in the Black Hills by exchange of school lands for Federal lands and recently the State has qualified for cooperation under the Clarke-McNary law.

On March 6, 1890, South Dakota passed a tree-planting bounty law, which provided that every person planting an acre or more of prairie land within 10 years after the passage of the act with not less than 900 per acre of any kind of forest trees and 100 or more of evergreens, and successfully growing and cultivating them for 3 years, would be entitled to receive for 10 years after the third season of such planting an annual bounty of $2 per acre for each acre of forest trees not to exceed 6 acres, and $1 for every 100 evergreens not to exceed 1,200.

Superseding the foregoing, a State law of 1920 provides for a bounty of $5 per acre, up to 10 acres, for a period of 10 years to any person "who, after the year 1920, shall have planted and successfully cultivated" not less than 150 trees per acre, with a showing of not less than 100 living trees per acre in any year for which the bounty is paid. A copy of the statute follows, as an example of such laws, which are more or less similar:

TREE BOUNTY

(From compiled Laws of South Dakota, 1929)

SECTION 8045. To Whom Paid.—Any person who, after the year 1920, shall have planted and successfully cultivated the number of forest or fruit trees or shrubs prescribed by this article and who shall have complied with the provisions of this article, shall be entitled to a bounty of five dollars ($5.00) per acre, on not to exceed ten acres, each year for the period of ten years, to be paid by the board of county commissioners of the county in which such trees are located, out of the general fund of such county; provided that such person shall continue to comply with the provisions (if this article.

SECTION 8046. Application for Bounty.—Any person desiring to secure such bounty shall file with the county auditor, on or before the first Monday in August, a correct plat designating the land upon which the trees are planted according to the United States government survey, together with an affidavit showing the number and varieties of trees planted, the date of planting and the cultivation of the same, corroborated by the affidavits of two freeholders residing in the vicinity.

SECTION 8047. Number of Trees to the Acre.—To secure such bounty there shall have been planted not less than one hundred and fifty trees to the acre, and there shall be not less than one hundred living trees per acre in any year for which such bounty is paid. Provided, that any trees or shrubbery planted after July 1st, 1927, may by resolution of the Board of County Commissioners passed at the first regular meeting of such board in January, of each year he required to be arranged and planted substantially as follows:

(a) Elms, ash, black walnut, boxelder, native cedars, Black Hills spruce, oak, cottonwood, willows, or other trees of like character not herein specifically mentioned, in rows forty feet apart and such trees twelve feet apart in each row.

(b) Russian olive and Caragana in rows thirty feet apart and such trees five feet apart in each row.

(c) Apple trees in rows forty feet apart and such trees forty feet apart in each row.

(d) Plum, pear, cherry, or other similar varieties not herein specifically mentioned, in rows thirty feet apart and such trees thirty feet apart in each row.

(a) Caragana, artisima, buckthorn, spiraea, common lilac, and other similar varieties of shrubs not herein specifically mentioned, in rows thirty feet apart and such plants one foot apart in each row.

(f) Lilac, snowball, and all other shrubs of a similar variety not herein specifically mentioned, in rows twenty feet apart and such plants five feet apart in each row.

NEBRASKA

Although Nebraska, the home of Arbor Day, has only about 3 percent of its area in native forests, it is credited with being the greatest tree-planting State in the Union.

The conservation and survey division of the University of Nebraska, which was established in 1921, includes a State forester. This organization has made a study of soils and climatic conditions in relation to tree growth and has promoted tree planting through its publications and in many other ways. There is also a State extension forester, who is on the staff of the State college of agriculture.

Veterans' organizations in Nebraska are active in their support of forestry. In 1933, the American Legion, within the assistance of the conservation division of the State university, conducted a tree-planting campaign, and in 1934 the Veterans of Foreign Wars began sponsoring a movement for a national arboretum near Nebraska City.

Congressman Luckey and Senator Burke have (in 1935) introduced identical bills into the Congress providing for the establishment of a forest experiment station for the Great Plains and Prairie States.

The State qualified early for cooperation in tree distribution under the Clarke-McNary Act, which is conducted by the agricultural extension service in cooperation with the Federal Government.

There is no State nursery, but tree-planting stock is obtained commercially and from the Forest Service nursery at Halsey (the Bessey Nursery) and distributed for planting windbreaks and woodlots at a cost to farmers of approximately $1 per hundred trees, or less in lots of more than 400 trees. In 1926, 34,000 trees were distributed to 105 farmers in 48 counties, and 53 percent of the trees lived. In 1927, 186,000 were supplied to 1,161 farmers in 92 counties; 700,000 were furnished in 1928 and a similar number in 1929. The activity has kept on increasing until, in 1934, the distribution was 1,125,000 trees.

Between Plattsmouth and Kearney the Burlington & Missouri Railroad in 1873 planted trees along 27 miles of cuts to prevent the snow from drifting into them.

Results of early plantings in most parts of the State were not altogether favorable because of improper selection of species and poor care. There was some planting in the prairies as early as 1854, but the greater part has been done since the early seventies, receiving its principal impetus from the establishment of Arbor Day in 1872 and the passage of the Timber Culture Act in 1873. By 1883 it was estimated that 250,000 acres had been planted. The early planters used such trees as cottonwood, ash, boxelder, locust, and catalpa, but relatively few pines and cedars. Fires and cattle damaged many of the groves, and few trees were irrigated.

The State gave aid to tree planters in 1869 by tax exemption up to $100 annually for 5 years if 1 or more acres were planted with trees spaced not more than 12 feet apart each way.

In 1894 the following list of trees was reported as having proved successful in the southwestern part of the State west of the one hundredth meridian:9 Cottonwood, black locust, honeylocust, black walnut, catalpa, white ash, green ash, pine, red cedar, hackberry, silver maple, Russian mulberry.

9EGLESTON, N. H. REPORT ON FORESTRY (1884), v. 4, 421 pp., illus. U. S. Dept. Agr., Div. Forestry, 1884.

The Nebraska College of Agriculture now issues a tree list in which the State is divided into five districts, each of which has particular requirements for tree growth. That part of the State lying west of the one hundredth meridian and wholly within the Great Plains area is designated district 5, for which the list of trees shows the following species as suitable: Honeylocust, American elm, green ash, black walnut, box elder, cottonwood, Norway poplar, Black Hills spruce, Koster's blue spruce, blue spruce, jack pine, ponderosa pine, and Austrian pine.

KANSAS

Kansas at one time maintained the lead as a tree-planting State but later lost it to Nebraska. About 2-1/2 percent of the State area was originally in native forest, confined mostly to stream valleys and bluffs in the eastern part, and to ravines and watercourses farther west.

Prairie fires started by the Indians in tribal controversies were an early source of destruction to native timber, but as these were checked, timber grew again along the courses of the streams and protected ravines.

Before and during the Civil War, Kansas settlers realized that the natural wooded areas within the State were being depleted for fuel, houses, and railroad building, and many artificial plantings were made. Officials of the Kansas Pacific Railroad, apparently sensing a prospective shortage, made experimental plantings at three towns along their line in the fall of 1870 and in the spring of 1871, at elevations, respectively, of 1,186, 2,019, and 3,175 feet, all between the 98th and the 102d meridians.

An important historical publication on Kansas tree culture is the Second Report on Forestry of the Kansas State Horticultural Society (1880), which is based on answers to a questionnaire received from persons in a large number of counties. It gives information on species adaptable to low and high lands, desirable spacings, methods of culture effect of trees on adjacent field crops, and the species, sizes, and locations of the oldest successful groves. Unfortunately, similar complete records for other States are not available.

Almost all the eastern counties of Kansas reported plantations successfully established in the years following the drought of 1860, and a few established in the late fifties. In counties farther west—McPherson, Mitchell, Reno, Saline, and Sedgewick—beginnings were made about 1870.

The above are some instances of tree planting antedating the Timber Culture Act. The planting sites were mostly on uplands, and no dissenting opinion was expressed as to the feasibility and desirability of spreading the gospel of tree planting on the Plains. All the correspondents stressed proper preparation of the soil and giving the trees the same culture as a crop of corn until the trees could shade the ground. Late seasonal cultivation was not advised. Those early experiences set forth principles that are considered as fundamentals in the inauguration of the present shelterbelt planting program. Had they been followed out consistently in early plantings, successes would have been much more numerous than have been recorded. With the rapid development of agriculture, however, there was an increasing tendency to neglect tree culture and concentrate on crops.

A few quotations from this historical report will illustrate how certain varieties are continually rediscovered. An Independence correspondent, after discussing the most important of the 60 native hardwoods of Kansas, wrote as follows:

If those counties which are nearly or quite destitute of natural forests are to be settled by an agricultural people, in such numbers as to form a farming community, with farms sufficiently small to admit of having neighbors and schools, and all the advantages and pleasures that flow from social intercourse and country life in pleasant country homes, surrounded with shade trees, fruit trees and flowers, or even if those farms are to produce the common necessaries of life, then in connection with the preservation and increase of the timber already growing, the planting of artificial forests, in a systematic and extensive way, becomes a necessity. But the cultivation of forests will not be successful in a general way, until the Government and the people are fully awake to its importance, and until the business is conducted by intelligent and skillful men, whose foresight reaches beyond the mere present, and who are working to build up for themselves and their children pleasant and permanent homes. The mere adventurer seldom if ever does anything to benefit the locality where he chances to stop; he only destroys what there may be around him, and leaves more desolation behind him than he found.

For wind-breaks, especially on division lines of farms, there can hardly be a better plan devised than to plant a double row of osage-orange, at the joint expense of the owners of the farms. Let a strip of land one rod wide be taken half from each farm, properly prepared, and two rows of osage-orange be set, with the plants a foot apart in the rows, which may be four feet apart. The land should be properly cultivated for a few years, and the young trees cut back, until the bottom of the hedge is sufficiently thick and strong, and then be allowed to grow at their will. They will soon form an impenetrable fence, and a very efficient wind-break. The rows will effectually support and protect each other, stop the snow, lessen the ill-effects of high winds, and form a safe and pleasant retreat for the birds.

The excellent advice of this contributor was well heeded in Kansas following 1880, but in the agricultural boom during and briefly following the World War the Osage-orange hedges, particularly, were heavily slaughtered. It may be questioned seriously whether this method of increasing the tillable area has paid, even up to the present.

Under the caption "Trees Successfully Grown in Kansas", the following interesting observations from Dickinson County, in the east-central part of the State, are found:

Honey locust.—On account of rapidity of growth and value of timber for fuel, posts, furniture, etc., we regard this native tree as very valuable. The idea seems to be common that this tree, like the common black locust, is liable to sprout from the roots, and is also subject to attacks of the "borer." For the benefit of this quite numerous class, it will be well to state that both ideas have no foundation in fact. The seed ripens in September. Sow in spring, near corn-planting time. Before sowing, scald the seed severely, by pouring boiling water over them.

Elm (red and white).—These two trees are beyond all question hardy, even in the most exposed positions. In rich soil they grow with great rapidity. They are, as far as our observation goes, entirely free from disease and insects. Grown thickly in artificial groves, they run up straight and tall. For isolated trees for shade, for avenues, or for group-planting for landscape effect, they are not excelled by any native tree. Michaux was right when he said that the "white elm was the most magnificent vegetable of the Temperate Zone." This special commendation of these two trees may be received with some doubt by those who have given the matter but little attention. We do not wish to convey the idea that exclusive plantations be made of any one tree. But example and fashion have too much influence in guiding tree planting. The soft maple, for instance, became, years ago, the popular tree for general planting all over the eastern portion of our State. Let us suppose that the elms had been the popular trees; how different would have been the face of the landscape there to day! The seed of the elms ripen in May. Sow at once, in a moist, shady spot. Plant out the trees next spring, preserving the tap-root.

Evergreen trees.—The number of these adapted to the climate of our State are not very numerous. The Scotch pine is easily transplanted, grows rapidly, and makes a strong, spreading tree. The Austrian pine is in every way a denser-growing and finer tree than the Scotch, and as a screen, is impenetrable to the wind. The red cedar is a tree of more moderate growth, but it is valuable in a shelterbelt. Avoid large trees of all of these three for transplanting. Choose sturdy growths one foot high, thrice transplanted. Plant early in the spring, mulch when planted; continue mulching for years, and success is certain.

Trees discarded.—Ailanthus, Catalpa bignonioides, black and yellow locust, Lombardy poplar, larch, and white willow; evergreen trees—balsam fir, Norway spruce, white pine, and arborvitae.

Observations.—We observe in our journeyings throughout the state, that those settlers who planted shelterbelts and groves are fixtures on their farms, while those who never planted a tree have pulled up stakes and gone elsewhere, and others of the same class are still going. Home attractions are lacking.

We notice always that trees are an ample protection from the most violent storm. While a northwest blizzard is howling in frigid fury across the open prairie, piercing the many wrappings of humanity, it is pleasant to have the homestead safely anchored on the southeast side of a dense grove.

We observe that our domestic animals appreciate the shelter afforded by trees . . .

We notice everywhere throughout this broad commonwealth, that plantations of trees effectually protect the garden, the orchard and field crops. This question was settled most conclusively during the spring of 1880. Sleet-laden branches were snapped by the billows of the wind. The tender inflorescence was chilled to death. The garden planted by the careful housewife was swept bare by the drifting winds, and the cereals sown in the fields were whipped and ruined irretrievably; and all this and more, because good sturdy trunks and stout pliant branches were not put in the ground years before to wrestle with the mighty winds and wrest from them their destroying power. Give us timber belts every half mile, good solid hedges every eighty rods, and then the Kansas farmer can laugh at the impetuous cold of the northwestern storm.

The following observations concerning experimental plantings at Manhattan are pertinent, in the main, today:

Considering the poverty of the soil in which they stand, the black walnuts, catalpa, osage-orange and cottonwood have made exceptionally fine growth. The wisdom of close planting is here apparent. Trees in these plats, standing about one foot by four apart, have served as a protection to each other—shading the trunks, rendering them less liable to the attacks of boring insects, and retaining the moisture of the soil. The tendency to a low, spreading growth, which is found on less dense plantations, is here corrected; and the trees take instead an upright form, with smooth, straight trunks branching high. This is, of course, a consideration of great importance where trees are grown for timber.

It may be added that the excellent showing of close plantings at an early age was often not maintained. because of common mistaken sentiment against thinning. Such an operation is now recognized as absolutely necessary to maintain the health of stands, and its necessity is no argument for wide spacing at the outset, which subjects the young trees to all the rigors of complete exposure.

A report by the writer in August 1902 on the sand hill and adjacent section in southwestern Kansas, near the one hundred and first meridian, stated that tree planting was entirely practicable on the heavier soils, and that it was believed locally that conditions in the sand hills were even more favorable. The fact that all the trees then growing in southwestern Kansas had been planted within 25 years gave

large hopes for the future of forestry in that section of the state. Kinsley, Dodge City, and Garden City are veritable forests of trees, and water is 100 to 140 feet below the surface In parts of Dodge City. Unfortunately, little has been demonstrated in the sandhill formation.

The report outlined the differences in physical characters of the sand formation in the Kansas area and the western Nebraska areas, the former being much coarser in texture. Demonstrations later, by the Forest Service, in the Kansas sand hills proved discouraging and were discontinued in 1915. These soils proved less favorable for tree growth than the harder soils. Moisture near the surface was deficient, and young trees were unable to survive until they could get their roots down.

At that time the following tree species were noted in plantings in and about Garden City: Cottonwood and three other species of poplar (Populus nigra, P. alba, P. balsamifera), juniper, boxelder, sycamore, black locust, honeylocust, ailanthus, elm, Scotch pine, mountain-ash, plum, birch, catalpa, two species of ash, spruce, Swiss stone pine, and Russian-olive.

This was 22 years after the 1880 reports previously quoted, which recorded more easterly plantings. Again, in 1932, 30 years later still, Fred R. Johnson, of the Forest Service, Denver, made the following comments on a number of successful plantings near Dodge City and Goodland, Kans.:

Any doubt about the practicability of tree planting in western Kansas is removed after seeing the foregoing groves. It is true that high-grade timber products are not secured, but that is not the main objective. Their protection value can scarcely be measured. It was of great interest to note that if trees are spaced close enough and the grove is large enough, forest conditions can eventually be secured and cultivation may be discontinued.

In this connection one planting 45 years old, near Goodland, was specifically cited.

The above observations for the southwest and northwest portions of the State are significant, because conditions there are considered less favorable, owing to excessive evaporation. than in most of the shelterbelt zone.

The first State forestry law in Kansas dates from 1887. This law allowed county commissioners to make some adjustment in taxes for tree planting, but practically no applications were made under it. A division of forestry was created in the State Agricultural College at Manhattan in 1909. There is also a State nursery at Hays.

Efforts at forestation in central and western Kansas since 1885 have resulted in a large number of good plantations, many poor ones, and, naturally, some failures due to variant ideas about tree planting and marked differences in conditions. There are enough successful plantations remaining to furnish lessons and encouragement for future planting under the shelterbelt program.

OKLAHOMA

Nearly 30 percent of the area of Oklahoma, confined mostly to the central and eastern parts, was originally in forest. Only the western one-third of Oklahoma, roughly between the 98th and 100th meridians, is in the Great Plains region, and much of this is covered by a scrubby growth of shin oak.

Oklahoma was peopled by Indians and was considered Indian Territory until 1889. The last tribes of plains Indians were moved into that territory in 1880. Prior to that time and following the Civil War, white cattlemen occupied a considerable part of the Oklahoma area, but white land settlement proper did not begin until 1889, when a clause attached to the Indian appropriation bill provided for the opening of "Old Oklahoma" or the "unassigned lands" to settlement. Oklahoma attained statehood in 1907.

Settlers, after the opening in 1889, planted considerable numbers of trees, most of which were black locust. Except on the bottom lands, however, they were largely killed out by borers.

In 1925 the legislature created a forestry commission. There are no forest-tax laws or tree-planting bounties. An interest in forestry, including the planting of trees and the reforestation of lands from which forests have been cut, is created and fostered in schools and colleges. Experimental and demonstrational tree planting was begun in the western part of the State in 1928, when five areas were planted under the supervision of the State forester.

TEXAS

It is estimated that about 18 percent of the gross area of Texas, mostly east of the 98th meridian, was originally in forests. This has been reduced to less than 10 percent of the gross area.

There are 4 State forests, totaling 6,293 acres, and 2 State nurseries with a combined capacity of 200,000 trees. There are no forest-taxation laws, but an effort is being made by the State forestry service and the Texas Forestry Association to have laws enacted that will encourage reforestation.

The public lands in Texas were owned by the State, and the Timber Culture Act did not apply to them. Despite lack of public aid, many plantings were made by the pioneers. Although most of them were neglected, there are isolated instances of success, even where groves were completely abandoned. On the High Plains of extreme western Texas, opened as wheat-farming territory more recently, tree planting has not been successful except with some degree of irrigation.

Experimental plantings in the Plains section have been at Dalhart, Amarillo, Lubbock, and Big Springs. At Dalhart, in 1908, the Forest Service directed the planting and furnished the stock. The species were ponderosa pine, black locust, American elm, green ash, Russian mulberry, Osage-orange, and red cedar. Catalpa was added later to replace ash. Russian mulberry, black locust, catalpa and American elm, in the order named, showed the best survivals.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

shelterbelt/sec8.htm Last Updated: 08-Jul-2011 |