|

Walnut Canyon National Monument Arizona |

|

NPS photo | |

The People Without Water

Dwellings sheltered by overhanging cliffs were home to Walnut Canyon's only permanent inhabitants more than 800 years ago. Inside the canyon and throughout the pine forests on its rims, these people made their living by farming, hunting deer and small game, gathering an assortment of useful plants, and trading. The people are today known as Sinagua—Spanish for "without water"—a tribute to their ability to turn a relatively dry region into a homeland.

These people were not the first to encounter Walnut Canyon and its abundance of plants and animals. Artifacts show that Archaic peoples, who traveled throughout the Southwest thousands of years ago, probably occupied the canyon seasonally. These nomads were long gone by the time their Sinagua successors appeared in the rugged volcanic terrain northeast of present-day Flagstaff more than 1,400 years ago. Perhaps these newcomers migrated from elsewhere, or perhaps they broke away from a local group and developed a distinct way of life. Like earlier inhabitants, they were probably attracted by the region's abundant plants and animals. But they were also farmers.

They built one-room pithouses near their fields, where they employed dry-farming techniques to grow corn and other crops. Archeologists once thought that debris from the eruption of nearby Sunset Crater sometime between 1040 and 1100 made the land more fertile, attracting many more people to the San Francisco volcanic field and bringing change to Sinagua life. Recent findings discredit this theory. Among the more likely influences were increased rainfall, new water-conserving farming practices, trade, and a general population increase in the Southwest. This period after the eruption, when Sinagua culture flourished, is marked by a change in architecture from the pithouse style. The large, above-ground villages at Wupatki and Elden Pueblo and Walnut Canyon's cliff dwellings, built between 1125 and 1250, date from this period. The canyon builders took advantage of natural recesses in the limestone walls. Over millions of years, flowing water eroded the softer rock layers, creating shallow caves.

These were also the years of the Sinagua culture's greatest geographical extent. Settlements ranged from the eastern slopes of the San Francisco Peaks northeast to the Little Colorado River and south to the Verde River valley. Trade items found in Sinagua dwellings include turquoise from the Santa Fe area, seashell ornaments from the Gulf of Mexico and the Gulf of California, and macaw feathers from Mexico. These goods may have been acquired by intermediaries who arranged trade between other groups of people.

The cliff dwellings were occupied for little more than 100 years. Why these people left is not clear. By 1250 they moved to new villages a few miles southeast along Anderson Mesa. It is generally believed that they were eventually assimilated into Hopi culture. The Hopi today call their ancestors the Hisatsinom ("people of long ago"). Their tradition suggests that these early migrations were part of a religious quest to have all clans come together.

Sinagua homes remained largely undisturbed until the 19th century. In the 1880s the railroad brought souvenir hunters to the ancient dwellings. Theft and destruction prompted local efforts to preserve the canyon and soon drew national support. In 1915 Walnut Canyon was declared a national monument. Hundreds of years have passed since Sinagua voices and laughter could be heard. Today, as you explore the trails, imagine the canyon alive with people carrying food and water, greeting one another, and building their cliffside homes.

600

Sinagua people arrive in San Francisco volcanic region northeast of

Flagstaff.

1040

Sunset Crater is created in several volcanic eruptions; Sinagua life

begins to change.

1100

Start of cliff dwelling construction in Walnut Canyon.

1250

Sinagua depart Flagstaff area for new villages to the south.

1400

Sinagua probably assimilated into Hopi culture.

1583

Antonio De Espejo opens Spanish exploration of northern Arizona.

1880s

Walnut Canyon becomes a popular destination for souvenir hunters.

1915

Walnut Canyon is proclaimed a national monument.

Reconstructing the Sinagua Past

It is difficult for us to know exactly how the Sinagua people lived. They left no written history when they departed the Flagstaff region sometime before 1250. In the 1880s pothunters removed many Sinagua possessions, dynamiting some of the cliff-dwelling walls to allow in more light for their search. To reconstruct what life must have been like, archeologists and anthropologists rely on what survived the centuries: building remains, ceramic fragments, tools, ornaments, and agricultural areas. Study of the rimtop and canyon dwelling sites reveals much about settlement patterns.

The Sinagua story has been pieced together by examining objects, comparing them with the ways of prehistoric groups elsewhere in the Southwest, and learning the oral traditions of the Hopi, the probable descendants of the Sinagua. Though incomplete, this information tells

Rimtop Croplands

The canyon rims, relatively flat with pockets of deep soil, were the main farmlands. Even in the semi-arid climate, water was usually available even though Walnut Creek probably did not flow all year. To conserve rainwater and collect soil, the people built terraces and small, rock check dams. Their major crops were a drought-resistant variety of corn and several kinds of beans and squash. Recent evidence shows that edible wild plants were just as important to the Sinagua diet as cultivated crops. More than 20 species of plants that could have been used for food and medicine still grow in the canyon. Among these are wild grape, serviceberry, elderberry, yucca, and Arizona black walnut. On the rims, edible wild plants were fewer but no less sought-after. Sinagua people also hunted deer, bighorn sheep, and numerous smaller animals.

Canyon Homes

Walnut Canyon homes were generally situated on cliffsides facing south and east to take advantage of warmth and sunlight. A few sites faced north and west; these may have been occupied during the warmer months. Although the cliff dwellings are the most visible ruins in the park, other archeological sites such as pithouses and free-standing pueblos dot the canyon rims.

Archeologists believe that it was the women who built the homes. The dwellings were made from shallow caves eroded out of the limestone cliffs by water and wind. To form walls, builders gathered limestone rocks, shaped them roughly, then cemented them together with a gold-colored clay found in deposits elsewhere in the canyon. Wooden beams reinforced the doorways. Finally, the walls were plastered with clay inside and out.

Plantlife Zones of Walnut Canyon

Walnut Canyon has an unusual array of biological communities, each characterized by different temperatures and plantlife, and determined largely by the amount of sunlight received. These plantlife zones are miniature versions of the zones spanning the West from Mexico to Canada—all within the canyon's 20-mile length and 400-foot depth. As you walk the Island Trail you travel from the Upper Sonoran desert, with yucca and prickly pear cactus, to the cooler, moister Pacific Northwestern forests of shade-tolerant shrubs and mixed conifers, including Douglas fir. Elsewhere in the canyon and on the rims are pinyon/juniper woodland and ponderosa pine/Gambel oak forest, found throughout the southwestern United States. At the bottom is the riparian (riverbank) community, which includes boxelder and the Arizona black walnut for which the canyon was named.

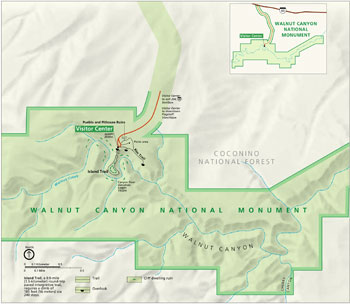

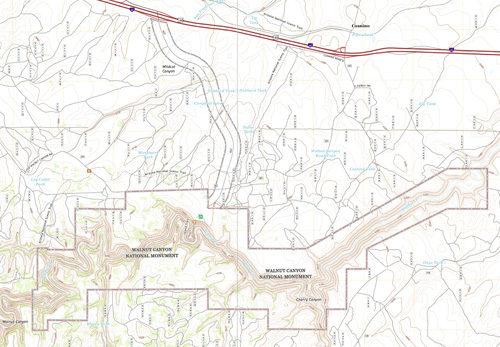

(click for larger maps) |

Prickly pear cactus, claret cup cactus, and yucca thrive in the Upper Sonoran desert plantlife zone, generally found on the south-facing slopes that receive full sunlight. Prickly pears have edible pads—spines removed—and sweet, juicy fruit. The yucca was especially useful to the Sinagua for food, soap, fiber, and construction material. The pinyon pine provided firewood, timber, black sap for dye and adhesives, and nutritious nuts. Ponderosa pine trees once covered the region surrounding the canyon; their long, straight trunks were prized for use in ladders and as support beams for structures.

Planning Your Visit

Hours and Facilities There is an entrance fee. The park is open daily except December 25. Hours are 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.; hours may be extended in summer. Note: The Island Trail closes one hour earlier. This part of Arizona is on Mountain Standard Time year-round.

The visitor center has an information desk, exhibits, a bookstore, and a panoramic view of the canyon. Two paved foot trails begin at the visitor center. The Island Trail, a 0.9-mile loop, passes 25 of the cliff dwelling rooms and takes you through different plantlife zones. There are sheer drops and a 185-foot climb (240 steps) back to the canyon rim. The 0.7-mile Rim Trail overlooks the canyon and passes the ruins of rimtop structures. The park has a picnic area. Campgrounds, lodging, and restaurants can be found nearby.

For a Safe Visit Elevation at the canyon rim is nearly 7,000 feet; be careful when attempting strenuous activity such as climbing stairs. • Drink plenty of water to prevent dehydration. • Picnics are permitted only in designated areas. Open fires are not allowed. • Stay on the trails when hiking; off-trail hiking is not allowed. • Pets are not permitted in the visitor center or on trails. • All plants, animals, and archeological objects within the park are protected by federal laws. There are substantial fines for damage or removal of these resources.

Location Walnut Canyon National Monument is 10 miles east of downtown Flagstaff. From I-40, take exit 204 and follow the entrance road.

Source: NPS Brochure (2019)

|

Establishment Walnut Canyon National Monument — November 30, 1915 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Survey of Prehistoric Sites in the Region of Flagstaff, Arizona Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 104 (Harold S. Colton, 1932)

Acoustic Monitoring Report, Walnut Canyon National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/NSNSD/NRR-2020/2135 (Jacob R. Job, June 2020

An Archaeological Survey of the South Rim of Walnut Canyon National Monument, Arizona Arizona State College Anthropological Papers No. 1 (Robert C. Euler, 1964)

An Assessment of the National Significance of Cultural Resources for the Walnut Canyon Special Resource Study (Ted Neff, Tim Gibbs, Kimberly Spurr, Kirk C. Anderson, Jason Nez, Bern Carey and David R. Wilcox, October 2011)

An Inventory of Paleontological Resources from Walnut Canyon National Monument, Arizona (Vincent L. Santucci and Luke Santucci, Jr., 1998)

Arizona Explorer Junior Ranger (Date Unknown)

Circular Relating to Historic and Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest and Their Preservation (Edgar L. Hewitt, 1904)

Cultural Affiliations of the Flagstaff Area National Monuments: Sunset Crater Volcano, Walnut Canyon, and Wupatki Final Report (Rebecca S. Toupal and Heather Fauland, September 26, 2007)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Walnut Canyon NM Headquarters Area Historic District (2011)

Draft Environmental Impact Statement/Draft General Management Plan: Walnut Canyon National Monument (September 2001)

Environmental Impact Statement/General Management Plan: Walnut Canyon National Monument Final (January 2007)

Fire History and Stand Structure of a Pinyon-Juniper Woodland at Walnut Canyon National Monument, Arizona Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit, Arizona, Technical Report No. 34 (Dell W. Despain and Jeffrey C. Mosley, August 1990)

Fire History of Walnut Canyon National Monument Draft (Kathy Davis, 1987)

Foundation Document, Walnut Canyon National Monument, Arizona (May 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Walnut Canyon National Monument, Arizona (January 2015)

Geologic Map of Walnut Canyon National Monument (May 2008)

Geologic Resource Evaluation Report, Walnut Canyon National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2008/040 (J. Graham, June 2008)

Historic Ranger Cabin and its Furnishings, Walnut Canyon National Monument, Arizona (David E. Purcell, December 23, 2019)

Historical Flow Regimes and Canyon Bottom Vegetation Dynamics at Walnut Canyon National Monument, Arizona (Peter G. Rowlands, Charles C. Avery, Nancy J. Brian and Heidemarie Johnson, April 1995)

Hydrologic Monitoring in Walnut Canyon National Monument; 2010-2011 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS-2012/359 (Ellen S. Soles and Stephen A. Monroe, September 2012)

Hydrologic Monitoring in Walnut Canyon National Monument; Water Years 2012 through 2014 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS-2015/965 (Stephen A. Monroe and Ellen S. Soles, August 2015)

Inventory of Exotic Species in the Resource Preservation Zone of Walnut Canyon National Monument, Arizona NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR-2010/314 (Ron Hiebert and Hillary Hudson, April 2010)

Inventory of Mammals at Walnut Canyon, Wupatki, and Sunset Crater National Monuments NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR-2009/278 (Charles Drost, December 2009)

Junior Arizona Archeologist (2016)

Land Protection Plan, Walnut Canyon National Monument, Arizona (August 1985)

Land Protection Plan, Walnut Canyon National Monument, Arizona (March 1990)

Logging Adjacent to Walnut Canyon and Sunset Crater Volcano National Monuments (Jeri DeYoung, 1999)

Natural and Cultural Resources Management Plan and Environmental Assessment, Walnut Canyon National Monument, Arizona (February 1976)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Old Headquarters (B-13) (F. Ross Holland, Jr., April 1972)

Walnut Canyon National Monument Archeological District (Anne Trinkle Jones, May 15, 1987)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Walnut Canyon National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SCPN/NRR-2018/1637 (Lisa Baril, Patricia Valentine-Darby, Kimberly Struthers and Paul Whitefield, May 2018)

Park Newspaper (InterPARK Messenger): c1990s • 1992

Park Newspaper (Ancient Times): 1998-1999 • 2000-2001 • 2003 • 2004 • 2006-2007 • 2007-2008 • 2016 • 2017

Rock Images of Walnut Canyon — A Virtual Tour (American Southwest Virtual Museum)

Soil Survey of Walnut Canyon National Monument, Arizona (2015)

The Lithological Section of Walnut Canyon, Arizona, with Relation to the Cliff-Dwellings of this and other Regions of Northwestern Arizona (H.W. and F.H. Shimer, extract from American Anthropologist, Vol. 12, 1910)

The Road Inventory for the Flagstaff Area Parks: Sunset Crater Volcano, Wupatki, and Walnut Canyon National Monuments (Federal Highway Administration, April 1999 )

Traditional Resource Use of the Flagstaff Area Monuments Final Report (Rebecca S. Toupal and Richard W. Stoffle, July 19, 2004)

Walnut Canyon Geological Report (HTML edition) Southwestern Monuments Special Report No. 7 (V.W. Vandiver, June 1936)

Walnut Canyon National Monument: An Archeological Overview Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology No. 4 (Patricia A. Gilman, 1976)

Walnut Canyon National Monument: An Archeological Survey Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology No. 39 (Anne R. Baldwin and J. Michael Bremer, 1986)

Walnut Canyon Settlement and Land Use The Arizona Archaeologist No. 23 (J. Michael Bremer, 1989; ©Arizona Archaeological Society, all rights reserved)

Walnut Canyon Special Study (January 2014)

waca/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025