|

War in the Pacific

Asan and Agat Invasion Beaches Cultural Landscapes Inventory |

|

| PART 2a |

HISTORY

First American Period 1898-1941

As a result of the Spanish American War, Spain relinquished possession of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam to the United States at the December 10, 1898 Treaty of Paris. Thus began the first period of American presence that would last until the Japanese captured Guam after they bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 (December 8, 1941 in Guam, across the International Date Line) (DOT 1967:9).

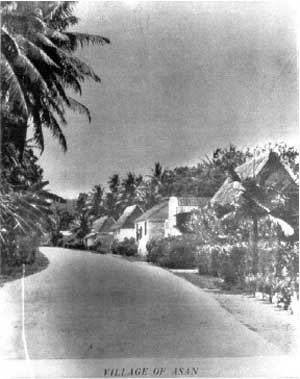

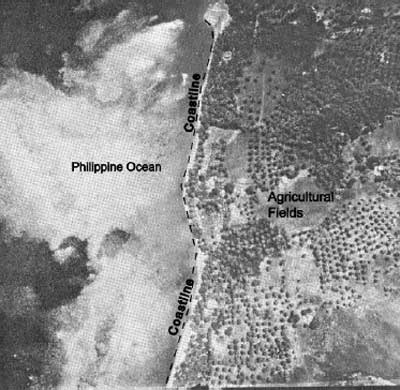

Pre-war Asan and Agat were small, lively villages with a scattering of homes with gardens and a road curving through each. The coast was lined with coconut trees which produced copra (coconut meat). During World War I, Guam's copra production rose to 1 million pounds per year (Rogers 1995:137). These villages also supported farming, ranching and fishing. Rice paddies were grown on the coastal flats as well as the flat inland portions of Asan and Agat.

Pre-war U.S. Military fortification of Guam was minimal, comprising of a naval base on the Orote Peninsula, military commissary, naval hospital in Agana, detention camp at Asan Beach, naval communication facilities, and a quartermaster depot at Asan Point.

The Sinking of the German Navy Ship Cormoran

During World War T, Japan declared war on Germany in early August of 1914, and the Japanese Navy then quickly seized all of Germany's holdings in Micronesia, Western Samoa, and Melanesia. A German ship, the Cormoran, fleeing the Japanese, was anchored and interned at Apra Harbor (located south of Asan Beach Unit) on December 14, 1914. The crewmembers were non-restricted and moved about freely on Guam until April 7, 1917, when President Wilson declared war on Germany. In a last attempt at patriotism, the German captain ordered his men to abandon the ship and threw the switch to blow it up. The enlisted crew was held at the Asan Beach detention facility from April 7 until April 29, 1917, when they were sent to the United States. After World War T, the crew were repatriated. The Cormoran remains sunken, 120-feet below the surface, in Apra Harbor (Rogers 1995:134-40).

Early Tensions with Japan in Micronesia

In 1917, Japan initiated a secret treaty with Britain, France and Russia to support Japan's claims in Micronesia in return for Britain, Australia, and New Zealand's retention of German colonies in the Pacific, south of the equator. The U.S. Navy learned of this treaty only at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. In response to the U.S. Navy's objections, the British proposed that former German colonies be administered by the new international organization established by the peace treaty, called the League of Nations. President Wilson reluctantly agreed and this became known as the Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 22, 1919. Although the Micronesian Islands were wards of the League of Nations, in reality, they were still possessions of Japan. Japan's presence and holdings in Micronesia solidified when the United States Senate refused to ratify the Versailles Treaty and consequently kept the United States out of the League of Nations (Rogers 1995:146).

To prevent a naval arms race that may have seen Japan become dominant in Asia, the new Harding Administration called a landmark Washington conference. On February 2, 1922, the Five Power Naval Treaty limited the numbers and tonnage of battleships and aircraft carriers that could be built by the five super-powers. In addition, the United States agreed to not fortify any Pacific island holdings west of Hawaii, for the next ten years. Therefore, no military fortifications and military airfields would be constructed on Guam (Rogers 1995:147). In 1932 a disarmament program, spurred by the Depression initiated the dismantling of fortifications and guns, the withdrawal of U.S. Marines, and the abandonment of military bases on Guam.

In 1936, Japan reneged on all previous arms treaties and began to fortify all of its holdings throughout Micronesia. Appeals from the U.S. Navy on Guam, recommending that Guam be developed as a major air and submarine base were rejected, and Congress would not authorize funding. The only action taken was to close Apra Harbor to all foreign vessels.

Once World War II broke out in Europe on September 1, 1939, all U.S. Military attention was directed there. Guam was placed in a Category F status, the lowest defense category of a United States territory that could not be defended. In 1940, President Roosevelt imposed a trade embargo against Japan in response to their aggressions in China. In 1941, Roosevelt finally froze all Japanese assets in the U.S. in response to their aggressions in French Indo-China. From that point on, war between the U.S. and Japan was inevitable.

In 1940 and again in 1944, the U.S. Navy engineers used the outer edge of Asan Point to quarry limestone. Pre and post-war Asan Beach was the site of a detention camp for foreign nationals and others who refused to swear allegiance to the United States flag.

In 1941, the U.S. Military just began to develop and construct roads on the island. Only one road that circled the entire island had been graded. Other roads had been extended and improved, particularly the western section near U.S. Navy facilities on the Orote Peninsula. Prewar Asan was a scattering of houses along a single coconut lined road that curved through the village. The road was a primary circulation route linking Agana (the capital city) to the east, and Piti, to the southwest, and was therefore known as the Agana-Piti Road. Just south of Adelup Point, the road curved closely to the beach before turning inland and entering the village of Asan. This was the foundation for Marine Drive. Historically, a short road branched from this road accessing a reef limestone quarry located at the outer end of Asan Point (ONI 1944:99). This quarry road is no longer there. Only two primary roads are shown near the Asan Beach area on 1940s military maps. One road runs along the beachfront extending north from Agana, south to the village of Agat. This is now Marine Drive. The other leads up over the ridges to Mt. Tenjo. This road was constructed in 1911 from Agana to Libugon (near Nimitz Hill) where a new Naval Radio Antenna was located and was later extended (1915) to Mount Tenjo. It overlooks Asan Beach (Olmo 1995:21). The Mt. Tenjo road now leads to the Mt. Tenjo and Mt. Chachao units of the park. Although these roads are outside the study area, they would have been major supply routes used by American and Japanese forces. A 1939 map shows three primary roads extending from the Agat Battlefield at the time of the American invasion: Old Agat Road, Agat-Sumay Road, and Harmon Road. Old Agat Road ran northeast out of Agat village towards Cabras Island and Asan Point. The Agat-Sumay Road branched north off of Old Agat Road and ran along the shore towards Orote Peninsula and Sumay. Harmon Road ran east from Agat inland towards Mt. Alifan. These three roads are still in use today.

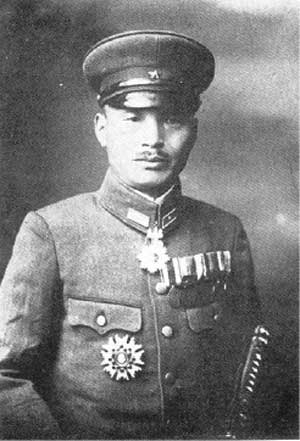

Early in 1941, Japanese military aircraft and ships stationed in Saipan began military reconnaissance of Guam. They took aerial photographs and began dispatching naval forces to the island. On December 4, Naval Governor Captain George J. McMillin received orders to destroy all secret and classified material held on Guam as well as military facilities, stores, and installations. The outbreak of war and invasion of Guam was expected, but still the United States and Chamorros believed the Japanese would be easily defeated. Major General Tomitara Hori was the commander of the South Seas Detached Force which was the main army assault unit during the capture of Guam.

At 0927, only hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, aerial bombings on Guam became part of the overall attack on American forces in the Pacific. A force of 5,000 Japanese troops invaded Guam on December 10, 1941. Primary targets were the Marine headquarters at Sumay and the Piti Navy Yard. Japanese naval planes, under the command of Vice Admiral Shigeyoshi Inouye, were stationed on Saipan, 110 miles from Guam (Olmo 1995:22). Apra Harbor fell into Japanese hands without a fight. Less than six hours after Japanese troops landed, Guam was theirs. Within a few hours, Governor McMillin surrendered the island to the Japanese naval commander. The entire island was captured virtually intact due to the failure of McMillin to give orders as planned, to destroy all secured and classified material as well as military facilities, stores, and installations to prevent their use by the Japanese. Overall, sixty-eight Americans and Chamorros were killed in the take-over (Rogers 1995:1658).

Historic photo of pre-war Asan Village (photo courtesy of War in

the Pacific National Historical Park Archives, n.d.).

Historic photo of pre-war Asan Beach (courtesy of the War in the

Pacific National Historical Park archies n.d.)

Historic photo of Asan Beach Stockade circa 1917 (courtesy of the War

in the Pacific National Historical Park archives, circa 1917).

Period of Japanese Occupation 1941-1944

Throughout the four years of Japanese occupation, Americans and Chamorro people associated with the U.S. Military were held as military prisoners of war. English and Chamorro languages were banned and the island was ruled by martial law. Repeated massacres and atrocities were commited against the Chamorro people. Rice on Guam was cultivated from pre-contact times. New rice paddies were developed along the coastal flats of Asan and Agat to support the Japanese troops. Historical photographs show that Asan Beach had a limited amount and Agat Beach had extensive rice paddies. As food became scarce, crops and food were seized from the Chamorro people. Local people were forced into labor with little or no subsistence rations. Limited food and medical supplies, along with harsh treatment of the young, elderly, sick resulted in the deaths of thousands of Guamanians. Japanese discipline varied from village to village depending on the personalities of those in charge. The Chamorros held fast to their American patriotism and the constant faith that American troops would return to liberate them (Rogers 1995:173).

Once the Japanese took the island, they did little to improve facilities or infrastructure. They did however recognize the suitability of the Orote Peninsula for an airstrip and constructed a 4500-foot coral-surfaced runway. In addition, the Japanese nearly completed a similar airstrip northeast of Agana and began clearing a third further north. The airstrip on the Orote Peninsula played a critical role in the American invasion strategy. Once troops secured Asan and Agat beaches, they were to advance and merge to isolate the peninsula and the airstrip. The Japanese expected this and reinforced the peninsula with defense positions and (haphazardly) placed landmines along existing roads.

As food became scarce, Chamorros reverted to subsistence farming and fishing. Carabao carts again became the primary means of transportation and eggs established a barter system between the Chamorro and Japanese. The Japanese imposed food quotas, demanding beef from ranchers and fruits and vegetables from farmers (Rogers 1995:170).

Thirty days prior to the landing on Guam in June 11, 1944, American air forces began bombing Asan and Agat beaches to clear Japanese positions. These bombings continued throughout June and July, indicating the target landing beaches to the Japanese. Thirteen days prior to the invasion, American ships and aircraft attacked in a constant 24-hour stream. This pre-invasion attack verified the American strategy to land on Asan and Agat beaches. Therefore, the Japanese concentrated their defense structures on the Orote Peninsula, between Asan and Agat beaches. This pre-war effort destroyed Japanese fortifications, most of Agana city, villages along Asan and Agat beaches as well as vegetation.

The Japanese began building defense structures in March of 1944, and so had less than three months to complete their defense strategies. General Takashina realized the natural topography and five coral rock outcroppings along Asan and Agat beaches were his best advantage. Both Asan and Agat beaches are coastal enclaves surrounded by slopes, ridges, and mountains that overlook these beaches and lagoons. These rock outcrops and high terrain became the driving force in the defensive strategy and placement of structures, obstacles, and troops. The elevated positions offered strategic viewplanes over the beaches below, and also served as superior locations for defensive military communications.

The Japanese had not planned any large-scale development on the island and therefore, had brought no construction supplies or equipment. They relied on the forced labor of the Chamorro people and hundreds of Koreans and Okinawans brought in as labor troops. American bulldozers and trucks, captured in 1941, were also put to use (Rogers 1995:175). Building materials were scarce. There were critical shortages of cement, reinforcing steel, lumber, and a wide range of needed hardware, which limited the kinds of fortification that could be built (Gailey 1988:40).

The defense structures included pillboxes, bunkers, and gun emplacements armed with machine guns, mortars, and light artillery, providing excellent fields of fire over the lagoons and beaches. These structures varied from well-built concrete-faced enclosures with multiple gun openings to crude and hurried concrete caps on holes dug in the dirt. Most structures were built into the coral rock outcroppings, using the natural features of caves and crevices. Some existing caves were extended and connected by the Japanese in order to have two or more openings, which let Japanese soldiers move undetected from the shoreline to ridge top. Many structures included inventive features (see buildings and structures section). Some pillboxes were so obviously sighted from the lagoon, they are thought to have been intentional decoys to distract attention away from well-camouflaged strongholds. Dummy cannons, made with coconut logs, were positioned in less defended areas. Offshore reefs and lagoons were laid with mines, logs, concrete, and/or barbed wire obstacles.

During the pre-invasion bombings, virtually all of the structures within Asan and Agat villages were demolished. The Japanese evacuated the Chamorros from their villages, apparently for security purposes and to prevent interference with the defense actions. It was a massive forced- march from the coastal areas inland, to concentration camps with no buildings, latrines, food or medicines. The largest camps were located at Talofofo and Manengon. Despite the continuous United States bombings, men and boys from the camps were often used as forced labor to build defense structures around the island.

Map of the planned Japanese Invasion of Guam (Rogers 1995).

Historic aerial photo of the Japanese Naval Task Force invasion of

Guam in 1941 (Lodge, 1998).

Historic photo of Major General Tomitara Hori, commander of the

Japanese South Seas Detach Force (Lodge, 1998).

Historic photo of Japanese constructed shore barriers (U.S. Marine

Corps 1944).

Historic photo of Japanese constructed shore barriers made of coconut

logs (U.S. Marine Corps 1944).

Historic photo of half finished Japanese gun emplacements with rebar

construction (U.S. Marines Corps 1944).

Historic photo of Japanese defense structure with a gun emplacement

recessed into the hillside. (U.S. Marine Corps 1944)

Historic photo of a Japanese pillbox recessed into the earth (U.S.

Marine Corps 1944).

American Strategy to Liberate Guam 1944

The United States military realized that the three major islands of the Mañana Islands, Guam, Saipan, and Tinian, were necessary for B-29 airbases. From these islands, the aircraft could complete round trip air raids to Japan. Possession of these islands would also sever the Japanese aircraft ferry route to Chuuk, Palau and Woleai. In addition, Guam's Apra Harbor would serve United States interests as a submarine refueling base, a good anchorage for an advance naval base, and a major supply center for the U.S. military forces. The justification to recapture the former United States territory was also driven by the need to liberate the Chamorros.

Original plans called for the assault on Guam to begin on June 18, 1944. However, U.S. forces landed on Saipan on June 15th, known as D-Day. They secured the airfields on June 18th, but did not secure the whole island until July 9th, 1944. The unexpected strength of the Japanese defense and the approach of the Japanese Combined Fleet from the Philippines towards the Mariana Islands lead to the postponement of the attack on Guam.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander In Chief of U.S. Pacific Fleet, decided upon July 21 as the invasion day instead of the scheduled date of June 18th. The Island of Guam was one of the U.S. military's strategic target islands in the Pacific Theater of War during World War II. The code name FORAGER was assigned to the recapture and liberation of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam. The code name for the recapture of Guam was STEVEDORE.

In April of 1944, U.S. submarines and long-range seaplanes began photographing and conducting reconnaissance on Guam. During the United States forty-three year presence on Guam, little to no mapping or physical information was recorded. Only poor quality aerial photographs, previous island stationed personnel, and a few Chamorros who served in the U.S. Navy were the source of information to chart road systems and topography. These sources were used to produce new maps for strategic planning of the invasion. The roads were built by the Seabees (U.S. Naval Construction Battalions).

The natural features and built infrastructure of the island were never recorded. Once the Japanese overtook and occupied the island, Navy intelligence had to rely on personnel who had previously been stationed on Guam and Chamorros who were serving in the U.S. Military for mapping field conditions. "Minor roads constructed by the enemy were not shown and in some cases there were errors in roads constructed by the U.S. Military prior to the occupation of the island by the Japanese" (Gailey 1988:60). Despite the limited knowledge of roads prior to July 21, 1944 and Japanese landmines placed along them, American troops still made use of existing roads. Landmines were often obvious and easy to deactivate. As soon as the landing beaches were secure by American troops, numerous bulldozers and tanks were brought ashore to expand the network of existing roads. Historic photographs show new roads being cut from the landing beach up the hills to expedite the transport of ammunition and supplies to advancing troops.

In May, American B-29 bombers began to bomb Saipan and Guam. On June 11-12, the Fast Carrier Task Force 58 destroyed 150 Japanese planes in an air assault. From this point on, the United States dominated the skies and seas of the Mariana Islands (Rogers 1995:176). On June 18-20, the American fleet turned to approach the oncoming Japanese fleet head-on. The United States lost 130 aircraft and the Japanese lost 3 aircraft carriers and 476 planes in the Battle of the Philippine Sea known as the "Great Marianas Turkey Shoot". This left Lieutenant General Takeshi Takashina commanding the General 29th Division and Japanese forces on Guam without backup to face the oncoming invasion (Rogers 1995:176).

Three weeks prior to landing, extensive air raids were carried out in an attempt to secure Asan and Agat beaches, where American Armed forces were to begin their initial assault. The offensive strategy, now apparent to the Japanese, was to land on Asan and Agat beaches and unite these forces by capturing the Orote Peninsula. The Orote Peninsula was edged with 200-foot cliffs overlooking the two beaches. It also contained the only functional airfield, crucial in order to secure and cut off Japanese supplies, and to bring in additional American supplies.

A critical error occurred when both the initial U.S. Military reconnaissance team and bombers neglected to identify five coral rock outcrops along Asan and Agat beaches. They were mistaken for sand dunes covered in vegetation and were therefore not targeted by the bombings. Japanese pillboxes and bunkers were clustered in these five coral outcrops: Apaca Point, Ga'an Point, Bangi Point (on Agat Beach) and Adelup Point and Asan Point (on Asan Beach). The structures survived the intensive pre-invasion bombing, and became Japanese strongholds. These strongholds had a significant influence on the outcome of the battles fought on the Asan and Agat beaches and they remain today as reminders of these events.

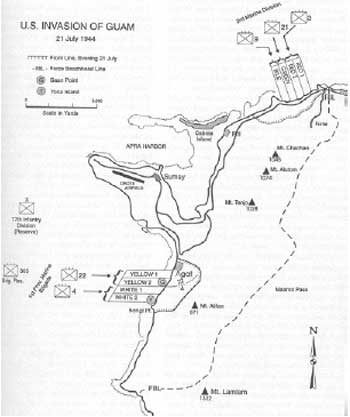

The U.S. Marines, responsible for combat, were to land on Asan and Agat beaches. Both beaches were divided up into four sections. Asan Beach, between Asan and Adelup points included (west-east) Blue, Green, Red 2, and Red 1 sections. The 3rd Marine division (Major General Allen H. Turnage, and Colonel W. Carvel Hall) would land on Asan Beach closest to Adelup point (red beach 1 and 2) and move to secure Chorito Cliff and Adelup Point. On Asan Beach closest to Asan Point, the 9th (Colonel Edward A. Craig) would land on blue beach and seize and hold the low ridges while the 21st Marines, commanded by Colonel Arthur H. Butler, would land on central green beach and drive inland and clear a way for expanding the beachhead (Roger 1995:182, Lodge 1998:38) (see invasion strategy map).

Agat Beach, often referred to as the Southern Assault Beach, was also divided into four units: (north-south) Yellow 1, Yellow 2, White 1, and White 2. Lieutenant Colonel Alan Shapley' s 4th Marines were to land far right, establish the beachhead and protect the brigade. The 305th RCT (from the 77th Army Infantry Division) were the brigade floating reserve commanded by Colonel Vincent J. Tanzola. Colonel Merlin F. Schneider's 22nd Marines would land far left, secure Agat Village and drive north towards the Orote peninsula. Beaches Yellow and White were targets of the First Provisional Marine Brigade led by Brigadier General Lemuel C. Shepherd with a back up of the 77th Army Infantry under Major General Andrew D. Bruce. Together these two forces made up the III Amphibious Corps. Once ashore, they would be under the command of Major General Roy S. Geiger of the U.S. Marine Corps (Rogers 1995:182, Lodge 1998:47-8).

Both units were to advance inland and establish the Force Beachhead Line (FBL) along the ridges from Fonte Plateau, Mounts Alutom, Tenjo and Alifan (see invasion strategy map). The securing of the FBL would secure the American position along the entire division front. After securing the FBL, forces were to converge and isolate the Orote Peninsula and the airfield upon the peninsula, and then continue to liberate the remainder of the island.

The Japanese had the advantage of the natural topography, which lent itself to defending the beaches and Orote Peninsula. The Americans had the advantage of three-to-one superiority in numbers of soldiers. The pre-invasion bombing from April through July eliminated many of the Japanese troops.

Beginning July 17, three U.S. Navy Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT's) spent four nights clearing underwater obstacles from the reefs in front of assault beaches. Obstacles consisted of palm log cribs filled with coral and concrete and linked with wire cable. By midnight prior to W-Day, demolition teams had eliminated 640 obstacles off-shore of Asan Beach and 300 off-shore of Agat Beach (Lodge 1998:35).

U.S. Military map planning invasion strategies on Asan and Agat

beaches (Rogers 1995:183).

American soldiers searching rice paddies and damaged coconut groves

for enemy troops in Asan (U.S. Marine Corps 1944).

Asan Invasion Beach, with damaged rice paddies and coconut groves in

the foreground and the U.S. War Ships in the background (U.S. Marine

Corps 1944).

Asan Invasion Beach, with damaged rice paddies and coconut groves in

the foreground and the U.S. War Ships in the background (U.S. Marine

Corps 1944).

Pre-invasion aerials of Bangi Point (Agat Beach Unit) with extensive

coconut groves and rice paddies in the background (U.S. Marine Corps

1944).

Post invasion photo of Agat Beach Unit with damaged vegetation (U.S.

Marine Corps 1944).

U.S. Marine Corps aerial photo of Agat Beach Head during the U.S.

Military invasion of Guam (U.S. Marine Corps 1944).

1944 pre-war military aerial photo of the Agat coastline with

scattered coconut groves along the coast and cultivated coastal

agricultural fields (Hunter-Anderson 1989).

Phase I W-Day 1944

Before dawn of July 21, 1944, three hours of incessant and deafening bombing trapped many Japanese inside their bunkers. Meanwhile the United States fleet of eleven battleships, twenty-four aircraft carriers, and 390 other ships gathered just off the western shore of Guam.

At 0829, the attack was directed at the 2000 yards of beach between Asan and Adelup points. The 3rd Marines landed on Red Beach 1, on the left flank. Being closest to Adelup Point, they soon realized that the Japanese were secured in effective defensive positions within the Adelup Point and upon Chonito Cliff, the high ground overlooking the beach. The 21st Marines assaulted Green Beach in the center with little resistence. The 9th Marine Division struck on Blue Beach, on the right flank, near Asan Point. Comprised of a little over six thousand men, they encountered the Japanese 320th Independent Infantry Battalion that was well entrenched in the caves along the limestone outcroppings. These outcroppings known as two 'devil's horns', Asan Point and Adelup Point, lie on either end of the 2,500 yard stretch of Asan Beach. Mortar and machine gun fire covered the beach from these caves and ridges. Especially debilitating was the fire coming from Adelup Point. One tunnel system, 400 yards long, connected Chorito Cliff with Adelup Point. Japanese troops could retire to positions on the back-slope of the ridge during intense shelling, and return out to the peninsula behind the U.S. Marines landing on the beach.

Road construction began as soon as equipment hit the shore. All the while, the invasion battle was at full tempo and the crew was often under sniper attacks. They worked 24-hours a day around a steady stream of two-way traffic. Rain, humidity and mosquitoes were a constant irritant. Engineering specifications for the highway were rigid as any built in major United States cities. Main arteries were to be four 11foot lanes, Curves were restricted to 6 degrees and grades could not exceed 6 percent. Rugged rock outcrops required extensive cuts. It was the rainy season meaning torrential downfalls reduced every road cut to muck and created as shortage of fill material. Fills exceeding 18-feet were required to cross gullies and swamps. Incredibly, in 60 days, a 12-mile, four-lane, super-highway with nine bridges was complete between Sumay and Agana.

The Americans realized that their worst obstacle would be the 'almost impossible' terrain facing them (Lodge 1998:40). Troops advancing toward Chorito Cliff and Bundschu Ridge took heavy losses. Four times they attempted to advance up rugged cliffs covered with sword grass. Four times they were pushed back. Climbing up the 60 degree slope required two handed climbing that made it impossible to return fire. Marines lay piled at the bottom of the ridges and the others were forced back to the beaches over and over until reaching success (Gailey 1988:95-97).

Heat of over 90 degrees, intense humidity, lack of drinking water, and motion sickness from the long confinement aboard the ships brought the efficiency rate of troops down to 75%. By mid-afternoon, many men were dropping from exhaustion. By day's end, the regiment invading Asan beach counted 231 killed or wounded. Of the 100 amphibious trucks (DUKW's) available, thirty-six were lost during the landing and immediate assault phase on Asan Beach.

At Agat, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade approached the beach, pushing in against Japanese troops from the 38th Infantry Regiment. Japanese troops were anchored in at Mt Alifan, Bangi, Apaca Point, and Ga'an Point. Defense structures and artillery were securely hidden within these rock outcroppings. In addition to Bangi Point and Apaca Point on either end, Ga'an Point was centered on Agat Beach and held effective fire power over north and south sections. These outcroppings supported the Japanese strategy to attack the enemy before they got a foothold on solid ground. The reef at Agat was much wider than Asan. Debilitating mortar and artillery fire poured down on American troops and amphibious vehicles as soon as they reached the reef edge. Japanese troops had a 75mm gun and 37mm gun mounted in concrete bunkers. Seventy-five marines were killed in the first wave, before they even reached the beach (Gailey 1998:97-99).

The first wave landed at 0829 and brutal mortar and artillery fire continued to reign down on the troops. In addition to the poor condition of the combat troops, there was a shortage of supplies, ammunition and water. Evacuation of the wounded was difficult without enough Landing Vehicle Transports (LVT's) and DUKW's. A direct mortar hit eliminated all medical personnel and supplies on Yellow Beach. In addition to these problems, General Shepard had no communication with the regimental CP's (command post) until after noon and was unable to call in the reserves until late in the day (Gailey 1998:101).

At 1400, the 2nd Battalion was ordered into Agat Beach. No LVT's could be spared to transport troops across the reef and into shore. They had to wade the 400 yards across coral heads and through shell craters while under direct enemy fire. Many soldiers, carrying as much as 50 pounds of equipment on their backs, slipped into water over their heads soaking vital communication equipment. The 2/305th unloaded and had to wade in at nightfall, narrowly escaping landing in enemy territory. By the end of the first day, casualties numbered 455, and the wounded over 536. Twenty-four, or more than one in eight LTV's were disabled (Gailey 1997:108).

Although the U.S. Marines had established themselves at each beachhead, their positions on Guam were less than secure since each beach was only a narrow strip of low ground encircled by outcrops, ridges and mountains. The Japanese were still controlling the strategic high ground with the ability to fire on almost any part of the beaches. However, lack of coordination and lack of any concentrated effort to create a breakthrough at a strategic point while they had the advantage was a critical mistake. "A careful look at the Japanese response to the relatively slight Marine gains during W-Day show that the decisions made by General Takashina and his subordinates during the afternoon of W-Day determined the outcome of the battle for Guam" (Gailey 1998:103).

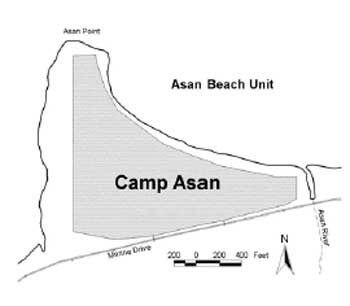

On W-Day, two non-combat units followed the combat troops, the U.S. Navy Seabees and a civil affairs group. The Seabees immediately set to work repairing and building roads, airstrips, and necessary installations. The multilane highway (Marine Drive) was constructed during this time. During the expansion of existing roads as well as building new roads, road cuts and removal of vegetation was necessary to achieve the construction goals. The Civil Affairs unit began running protective compounds for the vast amount of aged and sick Chamorro refugees brought back to the beachheads by combat marines. Camp Asan is believed to have served as the barracks and headquarters for the Seabees Island Command Troop. The camp consisted of approximately 40 quonset huts and outbuildings located between Asan Point and Asan River. The camp was in place by early 1945 and occupied until 1947.

Three days after W-Day, (24 July) the Southern Landing Force had its beachhead firmly established. The steep cliffs and ridges surrounding both Asan and Agat beaches again took their toll on the troops. Weighed down with the intense heat and humidity, and lacking adequate drinking water, the troops advanced on the ridges that sometimes required two handed climbing through razor sharp sword grass. The cliffs were so steep that supplies were sent up on ropes. Advancement over the ridges often required repeated efforts and caused significant losses (Gailey 1998:97).

After four days of continuous battle, the enemy was surrounded on the Orote Peninsula. The Army 77th Division had secured most of the FBL. Defense responsibility for the beach from Agat Village to Ga'an Point rested upon the 9th Defense Battalion. The Army 7th AAA (Automatic Weapons) Battalion guarded the coastline from Ga'an to Bangi Point (Lodge 1998:69-70).

Location of Camp Asan (CLI Team/PISO/2003).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

wapa/cri/part2a.htm

Last Updated: 03-May-2004