| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

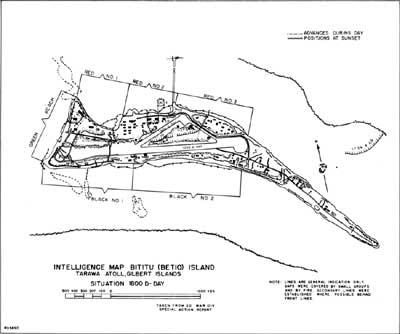

ACROSS THE REEF: The Marine Assault of Tarawa by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) D+1 at Betio, 21 November 1943 The tactical situation on Betio remained precarious for much of the 2d day. Throughout the morning, the Marines paid dearly for every attempt to land reserves or advance their ragged beachheads. The reef and beaches of Tarawa already looked like a charnel house. Lieutenant Lillibridge surveyed what he could see of the beach at first light and was appalled: ". . . a dreadful sight, bodies drifting slowly in the water just off the beach, junked amtracks." The stench of dead bodies covered the embattled island like a cloud. The smell drifted out to the line of departure, a bad omen for the troops of 1st Battalion, 8th Marines, getting ready to start their run to the beach.

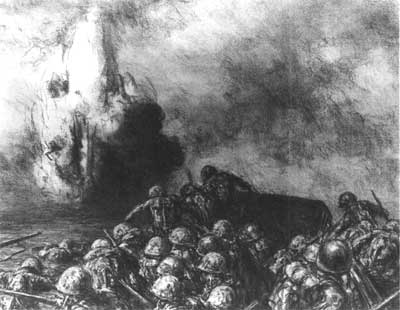

Colonel Shoup, making the most of faulty communications and imperfect knowledge of his scattered forces, ordered each landing team commander to attack: Kyle and Jordan to seize the south coast, Crowe and Ruud to reduce Japanese strongholds to their left and front, Ryan to seize all of Green Beach. Shoup's predawn request to General Smith, relayed through Major Tompkins and General Hermle, specified the landing of Hays' LT 1/8 on Red Beach Two "close to the pier." That key component of Shoup's request did not survive the tenuous communications route to Smith. The commanding general simply ordered Colonel Hall and Major Hays to land on Red Two at 0615. Hall and Hays, oblivious of the situation ashore, assumed 1/8 would be making a covered landing. The Marines of LT 1/8 had spent the past 18 hours embarked in LCVPs. During one of the endless circles that night, Chaplain W. Wyeth Willard passed Colonel Hall's boat and yelled, "What are they saving us for, the Junior Prom?" The troops cheered when the boats finally turned for the beach. Things quickly went awry. The dodging tides again failed to provide sufficient water for the boats to cross the reef. Hays' men, surprised at the obstacle, began the 500-yard trek to shore, many of them dangerously far to the right flank, fully within the beaten zone of the multiple guns firing from the re-entrant strongpoint. "It was the worst possible place they could have picked," said "Red Mike" Edson. Japanese gunners opened an unrelenting fire. Enfilade fire came from snipers who had infiltrated to the disabled LVTs offshore during the night. At least one machine gun opened up on the wading troops from the beached inter-island schooner Niminoa at the reef's edge. Hays' men began to fall at every hand.

The Marines on the beach did everything they could to stop the slaughter. Shoup called for naval gunfire support. Two of Lieutenant Colonel Rixey's 75mm pack howitzers (protected by a sand berm erected during the night by a Seabee bulldozer) began firing at the block houses at the Red 1/Red 2 border, 125 yards away, with delayed fuses and high explosive shells. A flight of F4F Wildcats attacked the hulk of the Niminoa with bombs and machine guns. These measures helped, but for the large part the Japanese caught Hays' lead waves in a withering crossfire. Correspondent Robert Sherrod watched the bloodbath in horror. "One boat blows up, then another. The survivors start swimming for shore, but machine-gun bullets dot the water all around them . . . . This is worse, far worse than it was yesterday." Within an hour, Sherrod could count "at least two hundred bodies which do not move at all on the dry flats."

First Lieutenant Dean Ladd was shot in the stomach shortly after jumping into the water from his boat. Recalling the strict orders to the troops not to stop for the wounded, Ladd expected to die on the spot. One of his riflemen, Private First Class T. F. Sullivan, ignored the orders and saved his lieutenant's life. Ladd's rifle platoon suffered 12 killed and 12 wounded during the ship-to-shore assault. First Lieutenant Frank Plant, the battalion air liaison officer, accompanied Major Hays in the command LCVP. As the craft slammed into the reef, Plant recalled Hays shouting "Men, debark!" as he jumped into the water. The troops that followed were greeted by a murderous fire. Plant helped pull the wounded back into the boat, noting that "the water all around was colored purple with blood." As Plant hurried to catch up with Major Hays, he was terrified at the sudden appearance of what he took to be Japanese fighters roaring right towards him. These were the Navy Wildcats aiming for the near by Niminoa. The pilots were exuberant but inconsistent: one bomb hit the hulk squarely; others missed by 200 yards. An angry David Shoup came up on the radio: "Stop strafing! Bombing ship hitting own troops!" At the end, it was the sheer courage of the survivors that got them ashore under such a hellish crossfire. Hays reported to Shoup at 0800 with about half his landing team. He had suffered more than 300 casualties; others were scattered all along the beach and the pier. Worse, the unit had lost all its flamethrowers, demolitions, and heavy weapons. Shoup directed Hays to attack westward, but both men knew that small arms and courage alone would not prevail against fortified positions. Shoup tried not to let his discouragement show, but admitted in a message to General Smith "the situation does not look good ashore." The combined forces of Majors Crowe and Ruud on Red Beach Three were full of fight and had plenty of weapons. But their left flank was flush against three large Japanese bunkers, each mutually supporting, and seemingly unassailable. The stubby Burns-Philp commercial pier, slightly to the east of the main pier, became a bloody "no man's land" as the forces fought for its possession. Learning from the mistakes of D-Day, Crowe insured that his one surviving Sherman tank was always accompanied by infantry. Crowe and Ruud benefitted from intensive air support and naval gunfire along their left flank. Crowe was unimpressed with the accuracy and effectiveness of the aviators ("our aircraft never did us much good"), but he was enthusiastic about the naval guns. "I had the Ringgold, the Dashiell, and the Anderson in support of me . . . . Anything I asked for I got from them. They were great!" On one occasion on D+1. Crowe authorized direct fire from a destroyer in the lagoon at a large command bunker only 50 yards ahead of the Marines. "They slammed them in there and you could see arms and legs and every thing just go up like that!" Inland from Red Beach Two, Kyle and Jordan managed to get some of their troops across the fire-swept air strip and all the way to the south coast, a significant penetration. The toehold was precarious, however, and the Marines sustained heavy casualties. "You could not see the Japanese," recalled Lieutenant Lillibridge, "but fire seemed to come from every direction." When Jordan lost contact with his lead elements, Shoup ordered him across the island to reestablish command. Jordan did so at great hazard. By the time Kyle arrived, Jordan realized his own presence was superfluous. Only 50 men could be accounted for of LT 2/2's rifle companies. Jordan organized and supplied these survivors to the best of his abilities, then—at Shoup's direction—merged them with Kyle's force and stepped back into his original role as an observer.

The 2d Marines' Scout Sniper Platoon had been spectacularly heroic from the very start when they led the assault on the pier just before H-Hour. Lieutenant Hawkins continuously set an example of cool disdain for danger in every tactical situation. His bravery was superhuman, but it could not last in the maelstrom. He was wounded by a Japanese mortar shell on D-Day, but shook off attempts to treat his injuries. At dawn on D+1 he led his men in attacking a series of strongpoints firing on LT 1/8 in the water. Hawkins crawled directly up to a major pillbox, fired his weapon point blank through the gun ports, then threw grenades inside to complete the job. He was shot in the chest, but continued the attack, personally taking out three more pill boxes. Then a Japanese shell nearly tore him apart. It was a mortal wound. The division mourned his death. Hawkins was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously. Said Colonel Shoup, "It's not often that you can credit a first lieutenant with winning a battle, but Hawkins came as near to it as any man could."

It was up to Major Mike Ryan and his makeshift battalion on the western end of Betio to make the biggest contribution to winning the battle on D+1. Ryan's fortunes had been greatly enhanced by three developments during the night: the absence of a Japanese spoiling attack against his thin lines, the repair of the medium tank "Cecilia," and the arrival of Lieutenant Thomas Greene, USN, a naval gunfire spotter with a fully functional radio. Ryan took his time organizing a coordinated attack against the nest of gun emplacements, pillboxes, and rifle pits concentrated on the southwest corner of the island. He was slowed by another failure in communications. Ryan could talk to the fire support ships but not to Shoup. It seemed to Ryan that it took hours for his runners to negotiate the gauntlet of fire back to the beach, radio Shoup's CP, and return with answers. Ryan's first message to Shoup announcing his attack plans received the eventual response, "Hold up—we are calling an air strike." It took two more runners to get the air strike cancelled. Ryan then ordered Lieutenant Greene to call in naval gunfire on the southwest targets. Two destroyers in the lagoon responded quickly and accurately. At 1120, Ryan launched a coordinated tank-infantry assault. Within the hour his patchwork force had seized all of Green Beach and was ready to attack eastward toward the airfield. Communications were still terrible. For example, Ryan twice reported the southern end of Green Beach to be heavily mined, a message that never reached any higher headquarters. But General Smith on board Maryland did receive direct word of Ryan's success and was overjoyed. For the first time Smith had the opportunity to land reinforcements on a covered beach with their unit integrity intact. General Smith and "Red Mike" Edson had been conferring that morning with Colonel Maurice G. Holmes, commanding the 6th Marines, as to the best means of getting the fresh combat team ashore. In view of the heavy casualties sustained by Hays' battalion on Red Beach Two, Smith was reconsidering a landing on the unknown eastern end of the island. The good news from Ryan quickly solved the problem. Smith ordered Holmes to land one battalion by rubber rafts on Green Beach, with a second landing team boated in LCVPs prepared to wade ashore in support. At this time Smith received reports that Japanese troops were escaping from the eastern end of Betio by wading across to Bairiki, the next is land. The Marines did not want to fight the same tenacious enemy twice. Smith then ordered Holmes to land one battalion on Bairiki to "seal the back door." Holmes assigned Lieutenant Colonel Raymond L. Murray to land 2/6 on Bairiki, Major "Willie K." Jones to land 1/6 by rubber boat on Green Beach, and Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth F. McLeod to be prepared to land 3/6 at any as signed spot, probably Green Beach. Smith also ordered the light tanks of Company B, 2d Tank Battalion, to land on Green Beach in support of the 6th Marines.

These tactical plans took much longer to execute than envisioned. Jones was ready to debark from Feland (APA 11) when the ship was suddenly ordered underway to avoid a perceived submarine threat. Hours passed before the ship could return close enough to Betio to launch the rubber boats and their LCVP tow craft. The light tanks were among the few critical items not truly combat loaded in their transports, being carried in the very bottom of the cargo holds. Indiscriminate unloading during the first 30 hours of the landing had further scrambled supplies and equipment in intervening decks. It took hours to get the tanks clear and loaded on board lighters.

Shoup was bewildered by the long delays. At 1345 he sent Jones a message: "Bring in flamethrowers if possible . . . . Doing our best." At 1525 he queried division about the estimated landing time of LT 1/6. He wanted Jones ashore and on the attack before dark. Meanwhile, Shoup and his small staff were beset by logistic support problems. Already there were teams organized to strip the dead of their ammunition, canteens, and first aid pouches. Lieutenant Colonel Carlson helped organize a "false beachhead" at the end of the pier. Most progress came from the combined efforts of Lieutenant Colonel Chester J. Salazar, commanding the shore party; Captain John B. McGovern, USN, acting as primary control officer on board the minesweeper Pursuit (AM 108); Major Ben K. Weatherwax, assistant division D-4; and Major George L. H. Cooper, operations officer of 2d Battalion, 18th Marines. Among them, these officers gradually brought some order out of chaos. They assumed strict control of supplies unloaded and used the surviving LVTs judiciously to keep the shuttle of casualties moving seaward and critical items from the pierhead to the beach. All of this was performed by sleepless men under constant fire. Casualty handling was the most pressing logistic problem on D+1. The 2d Marine Division was heroically served at Tarawa by its organic Navy doctors and hospital corpsmen. Nearly 90 of these medical specialists were themselves casualties in the fighting ashore. Lieutenant Herman R. Brukhardt, Medical Corps, USN, established an emergency room in a freshly captured Japanese bunker (some of whose former occupants "came to life" with blazing rifles more than once). In 36 hours, under brutal conditions, Brukhardt treated 126 casualties; only four died. At first, casualties were evacuated to troopships far out in the transport area. The long journey was dangerous to the wounded troops and wasteful of the few available LVTs or LCVPs. The Marines then began delivering casualties to the destroyer Ringgold in the lagoon, even though her sickbay had been wrecked by a Japanese five-inch shell on D-Day. The ship, still actively firing support missions, accepted dozens of casualties and did her best. Admiral Hill then took the risk of dispatching the troopship Doyen (APA 1) into the lagoon early on D+1 for service as primary receiving ship for critical cases. Lieutenant Commander James Oliver, MC, USN, led a five-man surgical team with recent combat experience in the Aleutians. In the next three days Oliver's team treated more than 550 severely wounded Marines. "We ran out of sodium pentathol and had to use ether," said Oliver, "although a bomb hit would have blown Doyen off the face of the planet." Navy chaplains were also hard at work wherever Marines were fighting ashore. Theirs was particularly heartbreaking work, consoling the wounded, administering last rites to the dying, praying for the souls of the dead before the bulldozer came to cover the bodies from the unforgiving tropical sun.

The tide of battle began to shift perceptibly towards the Americans by mid-afternoon on D+1. The fighting was still intense, the Japanese fire still murderous, but the surviving Marines were on the move, no longer gridlocked in precarious toeholds on the beach. Rixey's pack howitzers were adding a new definition for close fire support. The supply of ammunition and fresh water was greatly improved. Morale was up, too. The troops knew the 6th Marines was coming in soon. "I thought up until 1300 today it was touch and go," said Rixey, "then I knew we would win." By contrast, a sense of despair seemed to spread among the defenders. They had shot down the Marines at every turn, but with every fallen Marine, another would appear, rifle blazing, well supported by artillery and naval guns. The great Yogaki plan seemed a bust. Only a few aircraft attacked the island each night; the transports were never seriously threatened. The Japanese fleet never materialized. Increasingly, Japanese troops began committing suicide rather than risk capture. Colonel David M. Shoup, USMC

An excerpt from the field note book David Shoup carried during the battle of Tarawa reveals a few aspects of the personality of its enigmatic author: "If you are qualified, fate has a way of getting you to the right place at the right time—tho' sometimes it appears to be a long, long wait." For Shoup, the former farm boy from Battle Ground. Indiana, the combination of time and place worked to his benefit on two momentous occasions, at Tarawa in 1943, and as President Dwight D. Eisenhower's deep selection to become 22d Commandant of the Marine Corps in 1959. Colonel Shoup was 38 at the time of Tarawa, and he had been a Marine officer since 1926. Unlike such colorful contemporaries as Merritt Edson and Evans Carlson, Shoup had limited prior experience as a commander and only brief exposure to combat. Then came Tarawa, where Shoup, the junior colonel in the 2d Marine Division, commanded eight battalion landing teams in some of the most savage fighting of the war. Time correspondent Robert Sherrod recorded his first impression of Shoup enroute to Betio: "He was an interesting character, this Colonel Shoup. A squat, red-faced man with a bull neck, a hard-boiled, profane shouter of orders, he would carry the biggest burden on Tarawa." Another contemporary described Shoup as "a Marine's Marine," a leader the troops "could go to the well with." First Sergeant Edward G. Doughman, who served with Shoup in China and in the Division Operations section, described him as "the brainiest, nerviest, best soldiering Marine I ever met." It is no coincidence that Shoup also was considered the most formidable poker player in the division, a man with eyes "like two burn holes in a blanket." Part of Colonel Shoup's Medal of Honor citation reflects his strength of character:

Shoup was modest about his achievements. Another entry in his 1943 note book contains this introspection, "I realize that I am but a bit of chaff from the threshings of life blown into the pages of history by the unknown winds of chance." David Shoup died on 13 January 1983 at age 78 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. "In his private life;" noted the Washington Post obituary, "General Shoup was a poet." Shoup sensed this shift in momentum. Despite his frustration over the day's delays and miscommunications, he was buoyed enough to send a 1600 situation report to Julian Smith, which closed with these terse words that became a classic: "Casualties: many. Percentage dead: unknown. Combat efficiency: We are winning." At 1655, Murray's 2/6 landed against light opposition on Bairiki. During the night and early morning hours, Lieutenant Colonel George Shell's 2d Battalion, 10th Marines, landed on the same island and began registering its howitzers. Rixey's fire direction center on Betio helped this process, while the artillery forward observer attached to Crowe's LT 2/8 on Red Beach One had the unusual experience of adjusting the fire of the Bairiki guns "while looking into their muzzles." The Marines had practiced this earlier on New Zealand. Smith finally had artillery in place on Bairiki. Meanwhile, Major Jones and LT 1/6 were finally on the move. It had been a day of many false starts. At one point, Jones and his men had been debarking over the sides in preparation for an assault on the eastern end of the Betio when "The Word" changed their mission to Green Beach. When Feland finally returned to within reasonable range from the island, the Marines of LT 1/6 disembarked for real. Using tactics developed with the Navy during the Efate rehearsal, the Marines loaded on board LCVPs which towed their rubber rafts to the reef. There the Marines embarked on board their rafts, six to 10 troops per craft, and began the 1,000-yard paddle towards Green Beach. Major Jones remarked that he did not feel like "The Admiral of the Condom Fleet" as he helped paddle his raft shoreward. "Control was nebulous at best . . . the battalion was spread out over the ocean from horizon to horizon. We must have had 150 boats." Jones was alarmed at the frequent appearance of antiboat mines moored to coralheads beneath the surface. The rubber rafts passed over the mines without incident, but Jones also had two LVTs accompanying his ship-to-shore movement, each preloaded with ammo, rations, water, medical supplies, and spare radio equipment. Guided by the rafts, one of the LVTs made it ashore, but the second drifted into a mine which blew the heavy vehicle 10 feet into the air, killing most of the crew and destroying the supplies. It was a serious loss, but not critical. Well covered by Ryan's men, the landing force suffered no other casualties coming ashore. Jones' battalion became the first to land on Betio essentially intact. It was after dark by the time Jones troops assumed defensive positions behind Ryan's lines. The light tanks of Company B continued their attempt to come ashore on Green Beach, but the high surf and great distance between the reef and the beach greatly hindered landing efforts. Eventually, a platoon of six tanks managed to reach the beach; the remainder of the company moved its boats toward the pier and worked all night to get ashore on Red Beach Two. McLeod's LT 3/6 remained afloat in LCVPs beyond the reef, facing an uncomfortable night. That evening Shoup turned to Robert Sherrod and stated, "Well, I think we're winning, but the bastards have got a lot of bullets left. I think we'll clean up tomorrow."

After dark, General Smith sent his chief of staff, "Red Mike" Edson, ashore to take command of all forces on Betio and Bairiki. Shoup had done a magnificent job, but it was time for the senior colonel to take charge. There were now eight reinforced infantry battalions and two artillery battalions deployed on the two islands. With LT 3/6 scheduled to land early on D+2, virtually all the combat and combat support elements of the 2d Marine Division would be deployed. Edson reached Shoup's CP by 2030 and found the barrel-chested warrior still on his feet, grimy and haggard, but full of fight. Edson assumed command, allowing Shoup to concentrate on his own reinforced combat team, and began making plans for the morning. Years later, General Julian Smith looked back on the pivotal day of 21 November 1943 at Betio and admitted, "we were losing until we won!" Many things had gone wrong, and the Japanese had inflicted severe casualties on the attackers, but, from this point on, the issue was no longer in doubt at Tarawa.

|