| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

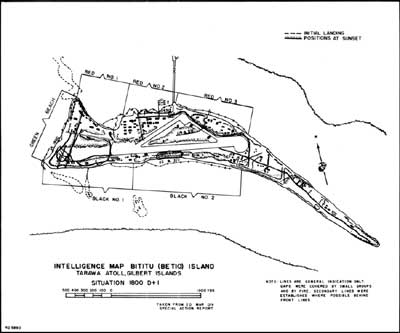

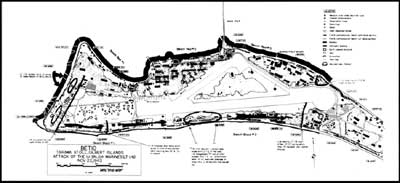

ACROSS THE REEF: The Marine Assault of Tarawa by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) The Third Day: D+2 at Betio, 22 November 1943 On D+2, Chicago Daily News war correspondent Keith Wheeler released this dispatch from Tarawa: "It looks as though the Marines are winning on this blood-soaked, bomb-hammered, stinking little abattoir of an island." Colonel Edson issued his attack orders at 0400. As recorded in the division's D-3 journal, Edson's plan for D+2 was this: "1/6 attacks at 0800 to the east along south beach to establish contact with 1/2 and 2/2. 1/8 attached to 2dMar attacks at daylight to the west along north beach to eliminate Jap pockets of resistance between Beaches Red 1 and 2. 8thMar (-LT 1/8) continues attack to east." Edson also arranged for naval gunfire and air support to strike the eastern end of the island at 20-minute interludes throughout the morning, beginning at 0700. McLeod's LT 3/6, still embarked at the line of departure, would land at Shoup's call on Green Beach.

The key to the entire plan was the eastward attack by the fresh troops of Major Jones' landing team, but Edson was unable for hours to raise the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, on any radio net. The enterprising Major Tompkins, assistant division operations officer, volunteered to deliver the attack order personally to Major Jones. Tompkins' hair-raising odyssey from Edson's CP to Green Beach took nearly three hours, during which time he was nearly shot on several occasions by nervous Japanese and American sentries. By quirk, the radio nets started working again just before Tompkins reached LT 1/6. Jones had the good grace not to admit to Tompkins that he already had the attack order when the exhausted messenger arrived. On Red Beach Two, Major Hays launched his attack promptly at 0700, attacking westward on a three-company front. Engineers with satchel charges and Bangalore torpedoes helped neutralize several inland Japanese positions, but the strong points along the re-entrant were still as dangerous as hornets' nests. Marine light tanks made brave frontal attacks against the fortifications, even firing their 37mm guns point blank into the embrasures, but they were inadequate for the task. One was lost to enemy fire, and the other two were withdrawn. Hays called for a section of 75mm halftracks. One was lost almost immediately, but the other used its heavier gun to considerable advantage. The center and left flank companies managed to curve around behind the main complexes, effectively cutting the Japanese off from the rest of the island. Along the beach, however, progress was measured in yards. The bright spot of the day for 1/8 came late in the afternoon when a small party of Japanese tried a sortie from the strongpoints against the Marine lines. Hays' men, finally given real targets in the open, cut down the attackers in short order. On Green Beach, Major Jones made final preparations for the assault of 1/6 to the east. Although there were several light tanks available from the platoon which came ashore the previous evening, Jones preferred the insurance of medium tanks. Majors "Willie K." Jones and "Mike" Ryan were good friends; Jones prevailed on their friendship to "borrow" Ryan's two battle-scarred Shermans for the assault. Jones ordered the tanks to range no further than 50 yards ahead of his lead company, and he personally maintained radio contact with the tank commander. Jones also assigned a platoon of water-cooled .30-caliber machine guns to each rifle company and attached his combat engineers with their flame throwers and demolition squads to the lead company. The nature of the terrain and the necessity for giving Hays' battalion wide berth made Jones constrain his attack to a platoon front in a zone of action only 100 yards wide. "It was the most unusual tactics that I ever heard of," recalled Jones. "As I moved to the east on one side of the airfield, Larry Hays moved to the west, exactly opposite . . . . I was attacking towards Wood Kyle who had 1st Battalion, 2d Marines." Jones' plan was sound and well executed. The advantage of having in place a fresh tactical unit with integrated supporting arms was immediately obvious. Landing Team 1/6 made rapid progress along the south coast, killing about 250 Japanese defenders and reaching the thin lines held by 2/2 and 1/2 within three hours. American casualties to this point were light. At 1100, Shoup called Jones to his CP to receive the afternoon plan of action. Jones' executive officer, Major Francis X. Beamer, took the occasion to replace the lead rifle company. Resistance was stiffening, the company commander had just been shot by a sniper, and the oppressive heat was beginning to take a toll. Beamer made superhuman efforts to get more water and salt tablets for his men, but several troops had already become victims of heat prostration. According to First Sergeant Lewis J. Michelony, Tarawa's sands were "as white as snow and as hot as red-white ashes from a heated furnace."

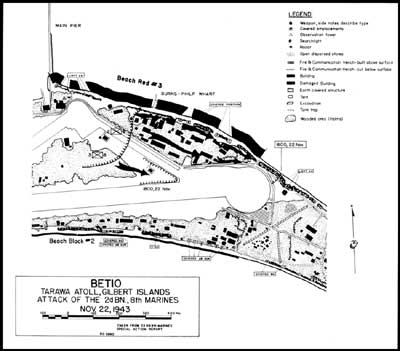

Back on Green Beach, now 800 yards behind LT 1/6, McLeod's LT 3/6 began streaming ashore. The landing was uncontested but nevertheless took several hours to execute. It was not until 1100, the same time that Jones' leading elements linked up with the 2d Marines, before 3/6 was fully established ashore. The attack order for the 8th Marines was the same as the previous day: assault the strongpoints to the east. The obstacles were just as daunting on D+2. Three fortifications were especially formidable: a steel pill-box near the contested Burns-Philp pier; a coconut log emplacement with multiple machine guns; and a large bombproof shelter further inland. All three had been designed by Admiral Saichero, the master engineer, to be mutually supported by fire and observation. And notwithstanding Major Crowe's fighting spirit, these strongpoints had effectively contained the combined forces of 2/8 and 3/8 since the morning of D-Day.

On the third day, Crowe reorganized his tired forces for yet another assault. First, the former marksmanship instructor obtained cans of lubricating oil and made his troops field strip and clean their Garands before the attack. Crowe placed his battalion executive officer, Major William C. Chamberlin, in the center of the three attacking companies. Chamberlin, a former college economics professor, was no less dynamic than his red-mustached commander. Though nursing a painful wound in his shoulder from D-Day, Chamberlin was a driving force in the repetitive assaults against the three strongpoints. Staff Sergeant Hatch recalled that the executive officer was a wild man, a guy anybody would be willing to follow." At 0930, a mortar crew under Chamberlin's direction got a direct hit on the top of the coconut log emplacement which penetrated the bunker and detonated the ammunition stocks. lt was a stroke of immense good fortune for the Marines. At the same time, the medium tank "Colorado" maneuvered close enough to the steel pillbox to penetrate it with direct 75mm fire. Suddenly, two of the three emplacements were overrun. The massive bombproof shelter, however, was still lethal. Improvised flanking attacks were shot to pieces before they could gather momentum. The only solution was to somehow gain the top of the sand-covered mound and drop explosives or thermite grenades down the air vents to force the defenders outside. This tough assignment went to Major Chamberlin and a squad of combat engineers under First Lieutenant Alexander Bonnyman. While riflemen and machine gunners opened a rain of fire against the strongpoint's firing ports, this small band raced across the sands and up the steep slope. The Japanese knew they were in grave danger. Scores of them poured out of a rear entrance to attack the Marines on top. Bonnyman stepped forward, emptied his flamethrower into the onrushing Japanese, then charged them with a carbine. He was shot dead, his body rolling down the slope, but his men were inspired to overcome the Japanese counterattack. The surviving engineers rushed to place explosives against the rear entrances. Suddenly, several hundred demoralized Japanese broke out of the shelter in panic, trying to flee eastward. The Marines shot them down by the dozens, and the tank crew fired a single "dream shot" canister round which dispatched at least 20 more. Lieutenant Bonnyman's gallantry resulted in a posthumous Medal of Honor, the third to be awarded to Marines on Betio. His sacrifice almost single-handedly ended the stalemate on Red Beach Three. Nor is it coincidence that two of these highest awards were received by combat engineers. The performances of Staff Sergeant Bordelon on D-Day and Lieutenant Bonnyman on D+2 were representative of hundreds of other engineers on only a slightly less spectacular basis. As an example, nearly a third of the engineers who landed in support of LT 2/8 became casualties. According to Second Lieutenant Beryl W. Rentel, the survivors used "eight cases of TNT, eight cases of gelatin dynamite, and two 54-pound blocks of TNT" to demolish Japanese fortifications. Rentel reported that his engineers used both large blocks of TNT and an entire case of dynamite on the large bombproof shelter alone. At some point during the confused, violent fighting in the 8th Marines' zone—and unknown to the Marines—Admiral Shibasaki died in his blockhouse. The tenacious Japanese commander's failure to provide backup communications to the above-ground wires destroyed during D-Day's preliminary bombardment had effectively kept him from influencing the battle. Japanese archives indicate Shibasaki was able to transmit one final message to General Headquarters in Tokyo early on D+2: "Our weapons have been destroyed and from now on everyone is attempting a final charge . . . . May Japan exist for 10,000 years!"

Admiral Shibasaki's counterpart, General Julian Smith, landed on Green Beach shortly before noon. Smith observed the deployment of McLeod's LT 3/6 inland and conferred with Major Ryan. But Smith soon realized he was far removed from the main action towards the center of the island. He led his group back across the reef to its landing craft and ordered the coxswain to make for the pier. At this point the commanding general received a rude introduction to the facts of life on Betio. Although the Japanese strongpoints at the re-entrant were being hotly besieged by Hays' 1/8, the defenders still held mastery over the approaches to Red Beaches One and Two. Well-aimed machine-gun fire disabled the boat and killed the coxswain; the other occupants had to leap over the far gunwale into the water. Major Tompkins, ever the right man in the right place, then waded through intermittent fire for half a mile to find an LVT for the general. Even this was not an altogether safe exchange. The LVT drew further fire, which wounded the driver and further alarmed the occupants. General Smith did not reach Edson and Shoup's combined CP until nearly 1400. "Red Mike" Edson in the meantime had assembled his major subordinate commanders and issued orders for continuing the attack to the east that afternoon. Major Jones' 1/6 would continue along the narrowing south coast, supported by the pack howitzers of 1/10 and all available tanks. Colonel Hall's two battalions of the 8th Marines would continue their advance along the north coast. Jump-off time was 1330. Naval gunfire and air support would blast the areas for an hour in advance.

Colonel Hall spoke up on behalf of his exhausted, decimated landing teams, ashore and in direct contact since D-Day morning. The two landing teams had enough strength for one more assault, he told Edson, but then they must get relief. Edson promised to exchange the remnants of 2/8 and 3/8 with Murray's fresh 2/6 on Bairiki at the first opportunity after the assault. Jones returned to his troops in his borrowed tank and issued the necessary orders. Landing Team 1/6 continued the attack at 1330, passing through Kyle's lines in the process. Immediately it ran into heavy opposition. The deadliest fire came from heavy weapons mounted in a turret-type emplacement near the south beach. This took 90 minutes to overcome. The light tanks were brave but ineffective. Neutralization took sustained 75mm fire from one of the Sherman medium tanks. Resistance was fierce throughout Jones' zone, and his casualties began to mount. The team had conquered 800 yards of enemy territory fairly easily in the morning, but could attain barely half that distance in the long afternoon.

The 8th Marines, having finally destroyed the three-bunker nemesis, made good progress at first, but then ran out of steam past the eastern end of the airfield. Shoup had been right the night before. The Japanese defenders may have been leaderless, but they still had an abundance of bullets and esprit left. Major Crowe pulled his leading elements back into defensive positions for the night. Jones halted, too, and placed one company north of the airfield for a direct link with Crowe. The end of the airstrip was unmanned but covered by fire. On nearby Bairiki, all of 2/10 was now in position and firing artillery missions in support of Crowe and Jones. Company B of the 2d Medical Battalion established a field hospital to handle the overflow of casualties from Doyen. Murray's 2/6, eager to enter the fray, waited in vain for boats to arrive to move them to Green Beach. Very few landing craft were available; many were crammed with miscellaneous supplies as the transports and cargo ships continued general unloading, regardless of the needs of the troops ashore. On Betio, Navy Seabees were already at work repairing the airstrip with bulldozers and graders despite enemy fire. From time to time, the Marines would call for help in sealing a bothersome bunker, and a bulldozer would arrive to do the job nicely. Navy beachmasters and shore party Marines on the pier continued to keep the supplies coming in, the wounded going out. At 1550, Edson requested a working party "to clear bodies around pier . . . hindering shore party operations." Late in the day the first jeep got ashore, a wild ride along the pier with every remaining Japanese sniper trying to take out the driver. Sherrod commented, "If a sign of certain victory were needed, this is it. The jeeps have arrived." The strain of the prolonged battle began to take effect. Colonel Hall reported that one of his Navajo Indian code-talkers had been mistaken for a Japanese and shot. A derelict, blackened LVT drifted ashore, filled with dead Marines. At the bottom of the pile was one who was still breathing, somehow, after two and a half days of unrelenting hell. "Water," he gasped, "Pour some water on my face, will you?"

Smith, Edson, and Shoup were near exhaustion themselves. Relatively speaking, the third day on Betio had been one of spectacular gains, but progress overall was maddeningly slow, nor was the end yet in sight. At 1600, General Smith sent this pessimistic report to General Hermle, who had taken his place on the flagship:

General Smith assumed command of operations ashore at 1930. By that time he had about 7,000 Marines ashore, struggling against perhaps 1,000 Japanese defenders. Updated aerial photographs revealed many defensive positions still intact throughout much of Betio's eastern tail. Smith and Edson believed they would need the entire 6th Marines to complete the job. When Colonel Holmes landed with the 6th Marines headquarters group, Smith told him to take command of his three landing teams by 2100. Smith then called a meeting of his commanders to as sign orders for D+3. Smith directed Holmes to have McLeod's 3/6 pass through the lines of Jones' 1/6 in order to have a fresh battalion lead the assault eastward. Murray's 2/6 would land on Green Beach and proceed east in support of McLeod. All available tanks would be assigned to McLeod (when Major Jones protested that he had promised to return the two Shermans loaned by Major Ryan, Shoup told him "with crisp expletives" what he could do with his promise). Shoup's 2d Marines, with 1/8 still attached, would continue to reduce the re-entrant strongpoints. The balance of the 8th Marines would be shuttled to Bairiki. And the 4th Battalion, 10th Marines would land its "heavy" 105mm guns on Green Beach to augment the fires of the two pack howitzer battalions already in action. Many of these plans were overcome by events of the evening.

The major catalyst that altered Smith's plans was a series of vicious Japanese counterattacks during the night of D+2/D+3. As Edson put it, the Japanese obligingly "gave us very able assistance by trying to counterattack." The end result was a dramatic change in the combat ratio between attackers and survivors the next day. Major Jones sensed his exposed forces would be the likely target for any Banzai attack and took precautions. Gathering his artillery forward observers and naval fire control spotters, Jones arranged for field artillery support starting 75 yards from his front lines to a point 500 yards out, where naval gunfire would take over. He placed Company A on the left, next to the airstrip, and Company B on the right, next to the south shore. He worried about the 150-yard gap across the runway to Company C, but that could not be helped. Jones used a tank to bring a stockpile of grenades, small arms ammunition, and water to be positioned 50 yards behind the lines. The first counterattack came at 1930. A force of 50 Japanese infiltrated past Jones' outposts in the thick vegetation and penetrated the border between the two companies south of the airstrip. Jones' reserve force, comprised of "my mortar platoon and my headquarters cooks and bakers and admin people," contained the penetration and killed the enemy in two hours of close-in fighting under the leadership of First Lieutenant Lyle "Spook" Specht. An intense fire from the pack howitzers of 1/10 and 2/10 prevented the Japanese from reinforcing the penetration. By 2130 the lines were stabilized. Jones asked Major Kyle for a company to be positioned 100 yards to the rear of his lines. The best Kyle could provide was a composite force of 40 troops from the 2d Marines. The Japanese struck Jones' lines again at 2300. One force made a noisy demonstration across from Company As lines—taunting, clinking canteens against their helmets, yelling Banzai!—while a second force attacked Company B with a silent rush. The Marines repulsed this attack, too, but were forced to use their machine guns, thereby revealing their positions. Jones asked McLeod for a full company from 3/6 to reinforce the 2d Marines to the rear of the fighting.

A third attack came at 0300 in the morning when the Japanese moved several 7.7mm machine guns into nearby wrecked trucks and opened fire on the Marine automatic weapons positions. Marine NCOs volunteered to crawl forward against this oncoming fire and lob grenades into the improvised machine gun nests. This did the job, and the battlefield grew silent again. Jones called for star shell illumination from the destroyers in the lagoon. At 0400, a force of some 300 Japanese launched a frenzied attack against the same two companies. The Marines met them with every available weapon. Artillery fire from 10th Marines howitzers on Red Beach Two and Bairiki Island rained a murderous crossfire. Two destroyers in the lagoon, Schroeder (DD 301) and Sigsbee (DD 502), opened up on the flanks. The wave of screaming attackers took hideous casualties but kept coming. Pockets of men locked together in bloody hand-to-hand fighting. Private Jack Stambaugh of B Company killed three screaming Japanese with his bayonet; an officer impaled him with his samurai sword; another Marine brained the officer with a rifle butt. First Lieutenant Norman K. Thomas, acting commander of Company B, reached Major Jones on the field phone, exclaiming "We're killing them as fast as they come at us, but we can't hold out much longer; we need reinforcements!" Jones' reply was tough, "We haven't got them; you've got to hold!"

Jones' Marines lost 40 dead and 100 wounded in the wild fighting, but hold they did. In an hour it was all over. The supporting arms never stopped shooting down the Japanese, attacking or retreating. Both destroyers emptied their magazines of 5-inch shells. The 1st Battalion, 10th Marines fired 1,300 rounds that long night, many shells being unloaded over the pier while the fire missions were underway. At first light, the Marines counted 200 dead Japanese within 50 yards of their lines, plus an additional 125 bodies beyond that range, badly mangled by artillery or naval gunfire. Other bodies lay scattered throughout the Marine lines. Major Jones had to blink back tears of pride and grief as he walked his lines that dawn. Several of his Marines grabbed his arm and muttered, "They told us we had to hold, and by God, we held."

|