| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

ACROSS THE REEF: The Marine Assault of Tarawa by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) D-Day at Betio, 20 November 1943 The crowded transports of Task Force 53 arrived off Tarawa Atoll shortly after midnight on D-Day. Debarkation began at 0320. The captain of the Zeilin (APA 3) played the Marines Hymn over the public address system, and the sailors cheered as the 2d Battalion, 2d Marines, crawled over the side and down the cargo nets. At this point, things started to go wrong. Admiral Hill discovered that the transports were in the wrong anchorage, masking some of the fire support ships, and directed them to shift immediately to the correct site. The landing craft bobbed along in the wake of the ships; some Marines had been halfway down the cargo nets when the ships abruptly weighed anchor. Matching the exact LVTs with their assigned assault teams in the darkness became haphazard. Choppy seas made cross-deck transfers between the small craft dangerous. Few tactical plans survive the opening rounds of execution, particularly in amphibious operations. "The Plan" for D-Day at Betio established H-Hour for the assault waves at 0830. Strike aircraft from the fast carriers would initiate the action with a half-hour bombing raid at 0545. Then the fire support ships would bombard the island from close range for the ensuing 130 minutes. The planes would return for a final strafing run at H-minus-five, then shift to inland targets as the Marines stormed ashore. None of this went according to plan. The Japanese initiated the battle. Alerted by the pre-dawn activities offshore, the garrison opened fire on the task force with their big naval guns at 0507. The main batteries of the battleships Colorado (BB 45) and Maryland commenced counterbattery fire almost immediately. Several 16-inch shells found their mark; a huge fireball signalled destruction of an ammunition bunker for one of the Japanese gun positions. Other fire support ships joined in. At 0542 Hill ordered "cease fire," expecting the air attack to commence momentarily. There was a long silence. The carrier air group had changed its plans, postponing the strike by 30 minutes. Inexplicably, that unilateral modification was never transmitted to Admiral Hill, the amphibious task force commander. Hill's problems were further compounded by the sudden loss of communications on his flagship Maryland with the first crashing salvo of the ship's main battery. The Japanese coastal defense guns were damaged but still dangerous. The American mix-up provided the defenders a grace period of 25 minutes to recover and adjust. Frustrated at every turn, Hill ordered his ships to resume firing at 0605. Suddenly, at 0610, the aircraft appeared, bombing and strafing the island for the next few minutes. Amid all this, the sun rose, red and ominous through the thick smoke.

The battleships, cruisers, and destroyers of Task Force 53 began a saturation bombardment of Betio for the next several hours. The awesome shock and sounds of the shelling were experienced avidly by the Marines. Staff Sergeant Norman Hatch, a combat photographer, thought to himself, "we just really didn't see how we could do [anything] but go in there and bury the people . . . this wasn't going to be a fight." Time correspondent Robert Sherrod thought, "surely, no mortal men could live through such destroying power . . . any Japs on the island would all be dead by now." Sherrod's thoughts were rudely interrupted by a geyser of water 50 yards astern of the ship. The Japanese had resumed fire and their targets were the vulnerable transports. The troop ships hastily got underway for the second time that morning. For Admiral Hill and General Julian Smith on board Maryland, the best source of information through out the long day would prove to be the Vought-Sikorsky Type OS2U Kingfisher observation aircraft launched by the battleships. At 0648, Hill inquired of the pilot of one float plane, "Is reef covered with water?" The answer was a cryptic "negative." At that same time, the LVTs of Wave One, with 700 infantrymen embarked, left the assembly area and headed for the line of departure.

The crews and embarked troops in the LVTs had already had a long morning, complete with hair-raising cross-deck transfers in the choppy sea and the unwelcome thrill of eight-inch shells landing in their proximity. Now they were commencing an extremely long run to the beach, a distance of nearly 10 miles. The craft started on time but quickly fell behind schedule. The LVT-1s of the first wave failed to maintain the planned 4.5-knot speed of advance due to a strong westerly current, decreased buoyancy from the weight of the improvised armor plating, and their overaged power plants. There was a psychological factor at work as well. "Red Mike" Edson had criticized the LVT crews for landing five minutes early during the rehearsal at Efate, saying, "early arrival inexcusable, late arrival preferable." Admiral Hill and General Smith soon realized that the three struggling columns of LVTs would never make the beach by 0830. H-Hour was postponed twice, to 0845, then to 0900. Here again, not all hands received this word. The destroyers Ringgold (DD 500) and Dashiell (DD 659) entered the lagoon in the wake of two minesweepers to provide close-in fire support. Once in the lagoon, the minesweeper Pursuit (AM 108) became the Primary Control Ship, taking position directly on the line of departure. Pursuit turned her searchlight seaward to provide the LVTs with a beacon through the thick dust and smoke. Finally, at 0824, the first wave of LVTs crossed the line, still 6,000 yards away from the target beaches. A minute later the second group of carrier aircraft roared over Betio, right on time for the original H-Hour, but totally unaware of the new times. This was another blunder. Admiral Kelly Turner had specifically provided all players in Operation Galvanic with this admonition: "Times of strafing beaches with reference to H-Hour are approximate; the distance of the boats from the beach is the governing factor." Admiral Hill had to call them off. The planes remained on station, but with depleted fuel and ammunition levels available.

The LVTs struggled shoreward in three long waves, each separated by a 300-yard interval: the 42 LVT-1s of Wave One, followed by 24 LVT-2s of Wave Two, and 21 LVT-2s of Wave Three. Behind the tracked vehicles came Waves Four and Five of LCVPs. Each of the assault battalion commanders were in Wave Four. Further astern, the Ashland ballasted down and launched 14 LCMs, each carrying a Sherman medium tank. Four other LCMs appeared carrying light tanks (37mm guns). Shortly before 0800, Colonel Shoup and elements of his tactical command post debarked into LCVPs from Biddle (APA 8) and headed for the line of departure. Close by Shoup stood an enterprising sergeant, energetically shielding his bulky radio from the salt spray. Of the myriad of communications blackouts and failures on D-Day, Shoup's radio would remain functional longer and serve him better than the radios of any other commander, American or Japanese, on the island. Admiral Hill ordered a cease fire at 0854, even though the waves were still 4,000 yards off shore. General Smith and "Red Mike" Edson objected strenuously, but Hill considered the huge pillars of smoke unsafe for overhead fire support of the assault waves. The great noise abruptly ceased. The LVTs making their final approach soon began to receive long range machine gun fire and artillery air-bursts. The latter could have been fatal to the troops crowded into open-topped LVTs, but the Japanese had overloaded the projectiles with high explosives. Instead of steel shell fragments, the Marines were "doused with hot sand." It was the last tactical mistake the Japanese would make that day. The previously aborted air strike returned at 0855 for five minutes of noisy but ineffective strafing along the beaches, the pilots again heeding their wristwatches instead of the progress of the lead LVTs. Two other events occurred at this time. A pair of naval landing boats darted towards the end of the long pier at the reef's edge. Out charged First Lieutenant Hawkins with his scout-sniper platoon and a squad of combat engineers. These shock troops made quick work of Japanese machine gun emplacements along the pier with explosives and flame throwers. Meanwhile, the LVTs of Wave One struck the reef and crawled effortlessly over it, commencing their final run to the beach. These parts of Shoup's landing plan worked to perfection. But the preliminary bombardment, as awesome and unprecedented as it had been, had failed significantly to soften the defenses. Very little ships' fire had been direct ed against the landing beaches themselves, where Admiral Shibasaki vowed to defeat the assault units at the water's edge. The well-protected defenders simply shook off the sand and manned their guns. Worse, the near-total curtailment of naval gun fire for the final 25 minutes of the assault run was a fateful lapse. In effect, the Americans gave their opponents time to shift forces from the southern and western beaches to reinforce northern positions. The defenders were groggy from the pounding and stunned at the sight of LVTs crossing the barrier reef, but Shibasaki's killing zone was still largely intact. The assault waves were greeted by a steadily increasing volume of combined arms fire. For Wave One, the final 200 yards to the beach were the roughest, especially for those LVTs approaching Red Beaches One and Two. The vehicles were hammered by well-aimed fire from heavy and light machine guns and 40mm antiboat guns. The Marines fired back, expending 10,000 rounds from the .50-caliber machine guns mounted forward on each LVT-1. But the exposed gunners were easy targets, and dozens were cut down. Major Drewes, the LVT battalion commander who had worked so hard with Shoup to make this assault possible, took over one machine gun from a fallen crewman and was immediately killed by a bullet through the brain. Captain Fenlon A. Durand, one of Drewes' company commanders, saw a Japanese officer standing defiantly on the sea wall waving a pistol, "just daring us to come ashore." On they came. Initial touchdown times were staggered: 0910 on Red Beach One; 0917 on Red Beach Three; 0922 on Red Beach Two. The first LVT ashore was vehicle number 4-9, nicknamed "My Deloris," driven by PFC Edward J. Moore. "My Deloris" was the right guide vehicle in Wave One on Red Beach One, hitting the beach squarely on "the bird's beak." Moore tried his best to drive his LVT over the five-foot seawall, but the vehicle stalled in a near-vertical position while nearby machine guns riddled the cab. Moore reached for his rifle only to find it shot in half. One of the embarked troops was 19-year-old Private First Class Gilbert Ferguson, who recalled what happened next on board the LVT: "The sergeant stood up and yelled 'everybody out.' At that very instant, machine gun bullets appeared to rip his head off . . ." Ferguson, Moore, and others escaped from the vehicle and dispatched two machine gun positions only yards away. All became casualties in short order. Very few of the LVTs could negotiate the seawall. Stalled on the beach, the vehicles were vulnerable to preregistered mortar and howitzer fire, as well as hand grenades tossed into the open troop compartments by Japanese troops on the other side of the barrier. The crew chief of one vehicle, Corporal John Spillane, had been a baseball prospect with the St. Louis Cardinals organization before the war. Spillane caught two Japanese grenades barehanded in mid-air, tossing them back over the wall. A third grenade exploded in his hand, grievously wounding him. The second and third waves of LVT-2s, protected only by 3/8-inch boiler plate hurriedly installed in Samoa, suffered even more intense fire. Several were destroyed spectacularly by large-caliber antiboat guns. Private First Class Newman M. Baird, a machine gunner aboard one embattled vehicle, recounted his or deal: "We were 100 yards in now and the enemy fire was awful damn intense and getting worse. They were knocking [LVTs] out left and right. A tractor'd get hit, stop, and burst into flames, with men jumping out like torches." Baird's own vehicle was then hit by a shell, killing the crew and many of the troops. "I grabbed my carbine and an ammunition box and stepped over a couple of fellas lying there and put my hand on the side so's to roll over into the water. I didn't want to put my head up. The bullets were pouring at us like a sheet of rain."

On balance, the LVTs performed their assault mission fully within Julian Smith's expectations. Only eight of the 87 vehicles in the first three waves were lost in the assault (although 15 more were so riddled with holes that they sank upon reaching deep water while seeking to shuttle more troops ashore). Within a span of 10 minutes, the LVTs landed more than 1,500 Marines on Betio's north shore, a great start to the operation. The critical problem lay in sustaining the momentum of the assault. Major Holland's dire predictions about the neap tide had proven accurate. No landing craft would cross the reef throughout D-Day. Shoup hoped enough LVTs would survive to permit wholesale transfer-line operations with the boats along the edge of the reef. It rarely worked. The LVTs suffered increasing casualties. Many vehicles, afloat for five hours already, simply ran of gas. Others had to be used immediately for emergency evacuation of wounded Marines. Communications, never good, deteriorated as more and more radio sets suffered water damage or enemy fire. The surviving LVTs continued to serve, but after about 1000 on D-Day, most troops had no other option but to wade ashore from the reef, covering distances from 500 to 1,000 yards under well-aimed fire.

Marines of Major Schoettel's LT 3/2 were particularly hard hit on Red Beach One. Company K suffered heavy casualties from the re-entrant strongpoint on the left. Company I made progress over the seawall along the "bird's beak," but paid a high price, including the loss of the company commander, Captain William E. Tatom, killed before he could even debark from his LVT. Both units lost half their men in the first two hours. Major Michael P. "Mike" Ryan's Company L, forced to wade ashore when their boats grounded on the reef, sustained 35 percent casualties. Ryan recalled the murderous enfilading fire and the confusion. Suddenly, "one lone trooper was spotted through the fire and smoke scrambling over a parapet on the beach to the right," marking a new landing point. As Ryan finally reached the beach, he looked back over his shoulder. "All [I] could see was heads with rifles held over them," as his wading men tried to make as small a target as possible. Ryan began assembling the stragglers of various waves in a relatively sheltered area along Green Beach. Major Schoettel remained in his boat with the remnants of his fourth wave, convinced that his landing team had been shattered beyond relief. No one had contact with Ryan. The fragmented reports Schoettel received from the survivors of the two other assault companies were disheartening. Seventeen of his 37 officers were casualties.

In the center, Landing Team 2/2 was also hard hit coming ashore over Red Beach Two. The Japanese strongpoint in the re-entrant between the two beaches played havoc among troops trying to scramble over the sides of their beached or stalled LVTs. Five of Company E's six officers were killed. Company F suffered 50 per cent casualties getting ashore and swarming over the seawall to seize a precarious foothold. Company G could barely cling to a crowded stretch of beach along the seawall in the middle. Two infantry platoons and two machine gun platoons were driven away from the objective beach and forced to land on Red Beach One, most joining "Ryan's Orphans." When Lieutenant Colonel Amey's boat rammed to a sudden halt against the reef, he hailed two passing LVTs for a transfer. Amey's LVT then became hung up on a barbed wire obstacle several hundred yards off Red Beach Two. The battalion commander drew his pistol and exhorted his men to follow him into the water. Closer to the beach, Amey turned to encourage his staff, "Come on! Those bastards can't beat us!" A burst of machine gun fire hit him in the throat, killing him instantly. His executive office, Major Howard Rice, was in another LVT which was forced to land far to the west, behind Major Ryan. The senior officer present with 2/2 was Lieutenant Colonel Walter Jordan, one of several observers from the 4th Marine Division and one of only a handful of survivors from Amey's LVT. Jordan did what any Marine would do under the circumstances: he assumed command and tried to rebuild the disjointed pieces of the landing team into a cohesive fighting force. The task was enormous. The only assault unit to get ashore without significant casualties was Major "Jim" Crowe's LT 2/8 on Red Beach Three to the left of the pier. Many historians have attributed this good fortune to the continued direct fire support 2/8 received throughout its run to the beach from the destroyers Ringgold and Dashiell in the lagoon. The two ships indeed provided outstanding fire support to the landing force, but their logbooks indicate both ships honored Admiral Hill's 0855 cease fire; thereafter, neither ship fired in support of LT 2/8 until at least 0925. Doubtlessly, the preliminary fire from such short range served to keep the Japanese defenders on the eastern end of the island buttoned up long after the cease fire. As a result, Crowe's team suffered only 25 casualties in the first three LVT waves. Company E made a significant penetration, crossing the barricade and the near taxiway, but five of its six officers were shot down in the first 10 minutes ashore. Crowe's LT 2/8 was up against some of the most sophisticated defensive positions on the island; three fortifications to their left (eastern) flank would effectively keep these Marines boxed in for the next 48 hours.

Major "Jim" Crowe—former enlisted man, Marine Gunner, distinguished rifleman, star football player—was a tower of strength throughout the battle. His trademark red mustache bristling, a combat shotgun cradled in his arm, he exuded confidence and professionalism, qualities sorely needed on Betio that long day. Crowe ordered the coxswain of his LCVP "put this god damned boat in!" The boat hit the reef at high speed, sending the Marines sprawling. Quickly recovering, Crowe ordered his men over the sides, then led them through several hundred yards of shallow water, reaching the shore intact only four minutes behind his last wave of LVTs. Accompanying Crowe during this hazardous effort was Staff Sergeant Hatch, the combat photographer. Hatch remembers being inspired by Crowe, clenching a cigar in his teeth and standing upright, growling at his men, "Look, the sons of bitches can't hit me. Why do you think they can hit you? Get moving. Go!" Red Beach Three was in capable hands.

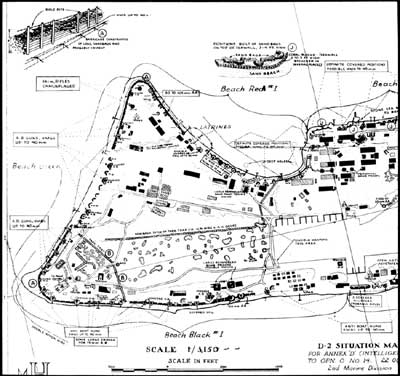

The situation on Betio by 0945 on D-Day was thus: Crowe, well established on the left with modest penetration to the airfield; a distinct gap between LT 2/8 and the survivors of LT 2/2 in small clusters along Red Beach Two under the tentative command of Jordan; a dangerous gap due to the Japanese fortifications at the re-entrant between beaches Two and One, with a few members of 3/2 on the left flank and the growing collection of odds and ends under Ryan past the "bird's beak" on Green Beach; Major Schoettel still afloat, hovering beyond the reef; Colonel Shoup likewise in an LCVP, but beginning his move towards the beach; residual members of the boated waves of the assault teams still wading ashore under increasing enemy fire; the tanks being forced to unload from their LCMs at the reef's edge, trying to organize recon teams to lead them ashore.

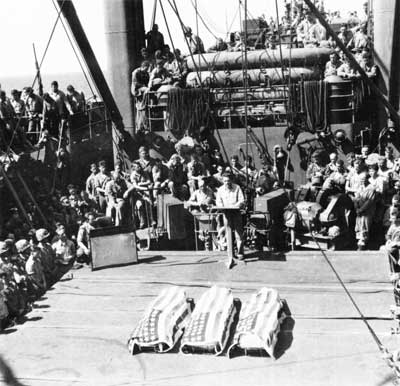

Communications were ragged. The balky TBX radios of Shoup, Crowe, and Schoettel were still operational. Otherwise, there was either dead silence or complete havoc on the command nets. No one on the flagship knew of Ryan's relative success on the western end, or of Amey's death and Jordan's assumption of command. Several echelons heard this ominous early report from an unknown source: "Have landed. Unusually heavy opposition. Casualties 70 per cent. Can't hold." Shoup ordered Kyle's LT 1/2, the regimental reserve, to land on Red Beach Two and work west. This would take time. Kyle's men were awaiting orders at the line of departure, but all were embarked in boats. Shoup and others managed to assemble enough LVTs to transport Kyle's companies A and B, but the third infantry company and the weapons company would have to wade ashore. The ensuing assault was chaotic. Many of the LVTs were destroyed enroute by antiboat guns which increasingly had the range down pat. At least five vehicles were driven away by the intense fire and landed west at Ryan's position, adding another 113 troops to Green Beach. What was left of Companies A and B stormed ashore and penetrated several hundred feet, expanding the "perimeter." Other troops sought refuge along the pier or tried to commandeer a passing LVT. Kyle got ashore in this fashion, but many of his troops did not complete the landing until the following morning. The experience of Lieutenant George D. Lillibridge of Company A, 1st Battalion, 2d Marines, was typical. His LVT driver and gunners were shot down by machine gun fire. The surviving crewman got the stranded vehicle started again, but only in reverse. The stricken vehicle then backed wildly though the entire impact zone before breaking down again. Lillibridge and his men did not get ashore until sunset. The transport Zeilin, which had launched its Marines with such fanfare only a few hours earlier, received its first clear signal that things were going wrong on the beach when a derelict LVT chugged close astern with no one at the controls. The ship dispatched a boat to retrieve the vehicle. The sailors discovered three dead men aboard the LVT: two Marines and a Navy doctor. The bodies were brought on board, then buried with full honors at sea, the first of hundreds who would be consigned to the deep as a result of the maelstrom on Betio. Communications on board Maryland were gradually restored to working order in the hours following the battleship's early morning duel with Betio's coast defense batteries. On board the flagship, General Julian Smith tried to make sense out of the intermittent and frequently conflicting messages coming in over the command net. At 1018 he ordered Colonel Hall to "chop" Major Robert H. Ruud's LT 3/8 to Shoup's CT Two. Smith further directed Hall to begin boating his regimental command group and LT 1/8 (Major Lawrence C. Hays, Jr.), the division reserve. At 1036, Smith reported to V Amphibious Corps: "Successful landing on Beaches Red Two and Three. Toe hold on Red One. Am committing one LT from Division reserve. Still encountering strong resistance throughout."

Colonel Shoup at this time was in the middle of a long odyssey trying to get ashore. He paused briefly for this memorable exchange of radio messages with Major Schoettel.

When Shoup's LCVP was stopped by the reef, he transferred to a passing LVT. His party included Lieutenant Colonel Evans F. Carlson, already a media legend for his earlier exploits at Makin and Guadalcanal, now serving as an observer, and Lieutenant Colonel Presley M. Rixey, commanding 1st Battalion, 10th Marines, Shoup's artillery detachment. The LVT made three attempts to land; each time the enemy fire was too intense. On the third try, the vehicle was hit and disabled by plunging fire. Shoup sustained a painful shell fragment wound in his leg, but led his small party out of the stricken vehicle and into the dubious shelter of the pier. From this position, standing waist-deep in water, surrounded by thousands of dead fish and dozens of floating bodies, Shoup manned his radio, trying desperately to get organized combat units ashore to sway the balance. For awhile, Shoup had hopes that the new Sherman tanks would serve to break the gridlock. The combat debut of the Marine medium tanks, however, was inauspicious on D-Day. The tankers were valorous, but the 2d Marine Division had no concept of how to employ tanks against fortified positions. When four Shermans reached Red Beach Three late in the morning of D-Day, Major Crowe simply waved them forward with orders to "knock out all enemy positions encountered." The tank crews, buttoned up under fire, were virtually blind. Without accompanying infantry they were lost piecemeal, some knocked out by Japanese 75mm guns, others damaged by American dive bombers. Six Shermans tried to land on Red Beach One, each preceded by a dismounted guide to warn of underwater shell craters. The guides were shot down every few minutes by Japanese marksmen; each time another volunteer would step forward to continue the movement. Combat engineers had blown a hole in the seawall for the tanks to pass inland, but the way was now blocked with dead and wounded Marines. Rather than run over his fellow Marines, the commander reversed his column and proceeded around the "bird's beak" towards a second opening blasted in the seawall. Operating in the turbid waters now without guides, four tanks foundered in shell holes in the detour. Inland from the beach, one of the surviving Shermans engaged a plucky Japanese light tank. The Marine tank demolished its smaller opponent, but not before the doomed Japanese crew released one final 37mm round, a phenomenal shot, right down the barrel of the Sherman.

By day's end, only two of the 14 Shermans were still operational, "Colorado" on Red Three and "China Gal" on Red One/Green Beach. Maintenance crews worked through the night to retrieve a third tank, "Cecilia," on Green Beach for Major Ryan. Attempts to get light tanks into the battle fared no better. Japanese gunners sank all four LCMs laden with light tanks before the boats even reached the reef. Shoup also had reports that the tank battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander B. Swenceski, had been killed while wading ashore (Swenceski, badly wounded, survived by crawling atop a pile of dead bodies to keep from drowning until he was finally discovered on D+1). Shoup's message to the flagship at 1045 reflected his frustration: "Stiff resistance. Need half tracks. Our tanks no good." But the Regimental Weapons Companys halftracks, mounting 75mm guns, fared no better getting ashore than did any other combat unit that bloody morning. One was sunk in its LCM by long-range artillery fire before it reached the reef. A second ran the entire gauntlet but became stuck in the loose sand at the water's edge. The situation was becoming critical. Amid the chaos along the exposed beachhead, individual examples of courage and initiative inspired the scattered remnants. Staff Sergeant William Bordelon, a combat engineer attached to LT 2/2, provided the first and most dramatic example on D-Day morning. When a Japanese shell disabled his LVT and killed most of the occupants enroute to the beach, Bordelon rallied the survivors and led them ashore on Red Beach Two. Pausing only to prepare explosive charges, Bordelon personally knocked out two Japanese positions which had been firing on the assault waves. Attacking a third emplacement, he was hit by machine gun fire, but declined medical assistance and continued the attack. Bordelon then dashed back into the water to rescue a wounded Marine calling for help. As intense fire opened up from yet another nearby enemy stronghold, the staff sergeant prepared one last demolition package and charged the position frontally. Bordelon's luck ran out. He was shot and killed, later to become the first of four men of the 2d Marine Division to be awarded the Medal of Honor. In another incident, Sergeant Roy W. Johnson attacked a Japanese tank single-handedly, scrambling to the turret, dropping a grenade inside, then sitting on the hatch until the detonation. Johnson survived this incident, but he was killed in subsequent fighting on Betio, one of 217 Marine Corps sergeants to be killed or wounded in the 76-hour battle. On Red Beach Three, a captain, shot through both arms and legs, sent a message to Major Crowe, apologizing for "letting you down." Major Ryan recalled "a wounded sergeant I had never seen before limping up to ask me where he was needed most." PFC Moore, wounded and disarmed from his experiences trying to drive "My Deloris" over the seawall, carried fresh ammunition up to machine gun crews the rest of the day until having to be evacuated to one of the transports. Other brave individuals retrieved a pair of 37mm antitank guns from a sunken landing craft, manhandled them several hundred yards ashore under nightmarish enemy fire, and hustled them across the beach to the seawall. The timing was critical. Two Japanese tanks were approaching the beach head. The Marine guns were too low to fire over the wall. "Lift them over," came the cry from a hundred throats, "LIFT THEM OVER!" Willing hands hoisted the 900-pound guns atop the wall. The gunners coolly loaded, aimed, and fired, knocking out one tank at close range, chasing off the other. There were hoarse cheers. Time correspondent Robert Sherrod was no stranger to combat, but the landing on D-Day at Betio was one of the most unnerving experiences in his life. Sherrod accompanied Marines from the fourth wave of LT 2/2 attempting to wade ashore on Red Beach Two. In his words:

Colonel Shoup, moving slowly towards the beach along the pier, ordered Major Ruud's LT 3/8 to land on Red Beach Three, east of the pier. By this time in the morning there were no organized LVT units left to help transport the reserve battalion ashore. Shoup ordered Ruud to approach as closely as he could by landing boats, then wade the remaining distance. Ruud received his assault orders from Shoup at 1103. For the next six hours the two officers were never more than a mile apart, yet neither could communicate with the other. Ruud divided his landing team into seven waves, but once the boats approached the reef the distinctions blurred. Japanese antiboat guns zeroed in on the landing craft with frightful accuracy, often hitting just as the bow ramp dropped. Survivors reported the distinctive "clang" as a shell impacted, a split second before the explosion. "It happened a dozen times," recalled Staff Sergeant Hatch, watching from the beach, "the boat blown completely out of the water and smashed and bodies all over the place." Robert Sherrod reported from a different vantage point, "I watched a Jap shell hit directly on a [landing craft] that was bringing many Marines ashore. The explosion was terrific and parts of the boat flew in all directions." Some Navy coxswains, seeing the slaughter just ahead, stopped their boats seaward of the reef and ordered the troops off. The Marines, many loaded with radios or wire or extra ammunition, sank immediately in deep water; most drowned. The reward for those troops whose boats made it intact to the reef was hardly less sanguinary: a 600-yard wade through withering crossfire, heavier by far than that endured by the first assault waves at H-Hour. The slaughter among the first wave of Companies K and L was terrible. Seventy percent fell attempting to reach the beach. Seeing this, Shoup and his party waved frantically to groups of Marines in the following waves to seek protection of the pier. A great number did this, but so many officers and noncommissioned officers had been hit that the stragglers were shattered and disorganized. The pier itself was a dubious shelter, receiving intermit tent machine-gun and sniper fire from both sides. Shoup himself was struck in nine places, including a spent bullet which came close to penetrating his bull neck. His runner crouching beside him was drilled between the eyes by a Japanese sniper. Captain Carl W. Hoffman, commanding 3/8's Weapons Company, had no better luck getting ashore than the infantry companies ahead. "My landing craft had a direct hit from a Japanese mortar. We lost six or eight people right there." Hoffman's Marines veered toward the pier, then worked their way ashore. Major Ruud, frustrated at being unable to contact Shoup, radioed his regimental commander, Colonel Hall: "Third wave landed on Beach Red 3 were practically wiped out. Fourth wave landed . . . but only a few men got ashore." Hall, himself in a small boat near the line of departure, was unable to respond. Brigadier General Leo D. ("Dutch") Hermle, assistant division commander, interceded with the message, "Stay where you are or retreat out of gun range." This added to the confusion. As a result, Ruud himself did not reach the pier until mid-afternoon. It was 1730 before he could lead the remnants of his men ashore; some did not straggle in until the following day. Shoup dispatched what was left of LT 3/8 in support of Crowe's embattled 2/8; others were used to help plug the gap between 2/8 and the combined troops of 2/2 and 1/2. Shoup finally reached Betio at noon and established a command post 50 yards in from the pier along the blind side of a large Japanese bunker, still occupied. The colonel posted guards to keep the enemy from launching any unwelcome sorties, but the approaches to the site it self were as exposed as any other place on the flat island. At least two dozen messengers were shot while bearing dispatches to and from Shoup. Sherrod crawled up to the grim-faced colonel, who admitted, "We're in a tight spot. We've got to have more men." Sherrod looked out at the exposed waters on both sides of the pier. Already he could count 50 disabled LVTs, tanks, and boats. The prospects did not look good. The first order of business upon Shoup's reaching dry ground was to seek updated reports from the landing team commanders. If anything, tactical communications were worse at noon than they had been during the morning. Shoup still had no contact with any troops ashore on Red Beach One, and now he could no longer raise General Smith on Maryland. A dire message came from LT 2/2: "We need help. Situation bad." Later a messenger arrived from that unit with this report: "All communications out except runners. CO killed. No word from E Company." Shoup found Lieutenant Colonel Jordan, ordered him to keep command of 2/2, and sought to reinforce him with elements from 1/2 and 3/8. Shoup gave Jordan an hour to organize and rearm his assorted detachments, then ordered him to attack inland to the airstrip and expand the beachhead.

Shoup then directed Evans Carlson to hitch a ride out to the Maryland and give General Smith and Admiral Hill a personal report of the situation ashore. Shoup's strength of character was beginning to show. "You tell the general and the admiral," he ordered Carlson, "that we are going to stick and fight it out." Carlson departed immediately, but such were the hazards and confusion between the beach and the line of departure that he did not reach the flagship until 1800. Matters of critical resupply then captured Shoups attention. Beyond the pier he could see nearly a hundred small craft, circling aimlessly. These, he knew, carried assorted supplies from the transports and cargo ships, unloading as rapidly as they could in compliance with Admiral Nimitz's stricture to "get the hell in, then get the hell out." The indiscriminate unloading was hindering prosecution of the fight ashore. Shoup had no idea which boat held which supplies. He sent word to the Primary Control Officer to send only the most critical supplies to the pier-head: ammunition, water, blood plasma, stretchers, LVT fuel, more radios. Shoup then conferred with Lieutenant Colonel Rixey. While naval gunfire support since the landing had been magnificent, it was time for the Marines to bring their own artillery ashore. The original plan to land the 1st Battalion/10th Marines, on Red One was no longer practical. Shoup and Rixey agreed to try a landing on the left flank of Red Two, close to pier. Rixey's guns were 75mm pack howitzers, boated in LCVPs. The expeditionary guns could be broken down for manhandling. Rixey, having seen from close at hand what happened when LT 3/8 had tried to wade ashore from the reef, went after the last remaining LVTs. There were enough operational vehicles for just two sections of Batteries A and B. In the confusion of transfer-line operations, three sections of Battery C followed the LVTs shoreward in their open boats. Luck was with the artillerymen. The LVTs landed their guns intact by late afternoon. When the the trailing boats hung up on the reef, the intrepid Marines humped the heavy components through the bullet-swept waters to the pier and eventually ashore at twilight. There would be close-in fire support available at daybreak. Julian Smith knew little of these events, and he continued striving to piece together the tactical situation ashore. From observation reports from staff officers aloft in the float planes, he concluded that the situation in the early afternoon was desperate. Although elements of five infantry battalions were ashore, their toehold was at best precarious. As Smith later recalled, "the gap between Red 1 and Red 2 had not been closed and the left flank on Red 3 was by no means secure." Smith assumed that Shoup was still alive and functioning, but he could ill afford to gamble. For the next several hours the commanding general did his best to influence the action ashore from the flagship. Smith's first step was the most critical. At 1331 he sent a radio message to General Holland Smith, reporting "situation in doubt" and requesting release of the 6th Marines to division control. In the meantime, having ordered his last remaining landing team (Hays' 1/8) to the line of departure, Smith began reconstituting an emergency division reserve comprised of bits and pieces of the artillery, engineer, and service troop units.

General Smith at 1343 ordered General Hermle to proceed to the end of the pier, assess the situation and report back. Hermle and his small staff promptly debarked from Monrovia (APA 31) and headed towards the smoking island, but the trip took four hours.

In the meantime, General Smith intercepted a 1458 message from Major Schoettel, still afloat seaward of the reef: "CP located on back of Red Beach 1. Situation as before. Have lost contact with assault elements." Smith answered in no uncertain terms: "Direct you land at any cost, regain control your battalion and continue the attack." Schoettel complied, reaching the beach around sunset. It would be well into the next day before he could work his way west and consolidate his scattered remnants.

At 1525, Julian Smith received Holland Smith's authorization to take control of the 6th Marines. This was good news. Smith now had four battalion landing teams (including 1/8) available. The question then became where to feed them into the fight without getting them chewed to pieces like Ruud's experience in trying to land 3/8. At this point, Julian Smith's communications failed him again. At 1740, he received a faint message that Hermle had finally reached the pier and was under fire. Ten minutes later, Smith ordered Hermle to take command of all forces ashore. To his subsequent chagrin, Hermle never received this word. Nor did Smith know his message failed to get through. Hermle stayed at the pier, sending runners to Shoup (who unceremoniously told him to "get the hell out from under that pier!") and trying with partial success to unscrew the two-way movement of casualties out to sea and supplies to shore. Throughout the long day Colonel Hall and his regimental staff had languished in their LCVPs adjacent to Hays' LT 1/8 at the line of departure, "cramped, wet, hungry, tired and a large number . . . seasick." In late afternoon, Smith abruptly ordered Hall to land his remaining units on a new beach on the northeast tip of the island at 1745 and work west towards Shoup's ragged lines. This was a tremendous risk. Smith's overriding concern that evening was a Japanese counterattack from the eastern tail of the island against his left flank (Crowe and Ruud). Once he had been given the 6th Marines, Smith admitted he was "willing to sacrifice a battalion landing team" if it meant saving the landing force from being overrun during darkness.

Fortunately, as it turned out, Hall never received this message from Smith. Later in the afternoon, a float plane reported to Smith that a unit was crossing the line of departure and heading for the left flank of Red Beach Two. Smith and Edson assumed it was Hall and Hays going in on the wrong beach. The fog of war: the movement reported was the beginning of Rixey's artillerymen moving ashore. The 8th Marines spent the night in its boats, waiting for orders. Smith did not discover this fact until early the next morning. On Betio, Shoup was pleased to receive at 1415 an unexpected report from Major Ryan that several hundred Marines and a pair of tanks had penetrated 500 yards beyond Red Beach One on the western end of the island. This was by far the most successful progress of the day, and the news was doubly welcome because Shoup, fearing the worst, had assumed Schoettel's companies and the other strays who had veered in that direction had been wiped out. Shoup, however, was unable to convey the news to Smith. Ryan's composite troops had indeed been successful on the western end. Learning quickly how best to operate with the medium tanks, the Marines carved out a substantial beachhead, overrunning many Japanese turrets and pillboxes. But aside from the tanks, Ryan's men had nothing but infantry weapons. Critically, they had no flamethrowers or demolitions. Ryan had learned from earlier experience in the Solomons that "positions reduced only with grenades could come alive again." By late afternoon, he decided to pull back his thin lines and consolidate. "I was convinced that without flamethrowers or explosives to clean them out we had to pull back . . . to a perimeter that could be defended against counterattack by Japanese troops still hidden in the bunkers." The fundamental choice faced by most other Marines on Betio that day was whether to stay put along the beach or crawl over the seawall and carry the fight inland. For much of the day the fire coming across the top of those coconut logs was so intense it seemed "a man could lift his hand and get it shot off." Late on D-Day, there were many too demoralized to advance. When Major Rathvon McC. Tompkins, bearing messages from General Hermle to Colonel Shoup, first arrived on Red Beach Two at the foot of the pier at dusk on D-Day, he was appalled at the sight of so many stragglers. Tompkins wondered why the Japanese "didn't use mortars on the first night. People were lying on the beach so thick you couldn't walk." Conditions were congested on Red Beach One, as well, but there was a difference. Major Crowe was every where, "as cool as ice box lettuce." There were no stragglers. Crowe constantly fed small groups of Marines into the lines to reinforce his precarious hold on the left flank. Captain Hoffman of 3/8 was not displeased to find his unit suddenly integrated within Crowe's 2/8. And Crowe certainly needed help as darkness began to fall. "There we were," Hoffman recalled, "toes in the water, casualties everywhere, dead and wounded all around us. But finally a few Marines started inching forward, a yard here, a yard there." It was enough. Hoffman was soon able to see well enough to call in naval gunfire support 50 yards ahead. His Marines dug in for the night.

West of Crowe's lines, and just inland from Shoup's command post, Captain William T. Bray's Company B, 1/2, settled in for the expected counterattacks. The company had been scattered in Kyle's bloody landing at mid-day. Bray reported to Kyle that he had men from 12 to 14 different units in his company, including several sailors who swam ashore from sinking boats. The men were well armed and no longer strangers to each other, and Kyle was reassured. Altogether, some 5,000 Marines had stormed the beaches of Betio on D-Day. Fifteen hundred of these were dead, wounded, or missing by nightfall. The survivors held less than a quarter of a square mile of sand and coral. Shoup later described the location of his beachhead lines the night of D-Day as "a stock market graph." His Marines went to ground in the best fighting positions they could secure, whether in shellholes inland or along the splintered sea wall. Despite the crazy-quilt defensive positions and scrambled units, the Marines' fire discipline was superb. The troops seemed to share a certain grim confidence; they had faced the worst in getting ashore. They were quietly ready for any sudden banzai charges in the dark. Offshore, the level of confidence diminished. General Julian Smith on Maryland was gravely concerned. "This was the crisis of the battle," he recalled. "Three-fourths of the Island was in the enemy's hands, and even allowing for his losses he should have had as many troops left as we had ashore." A concerted Japanese counterattack, Smith believed, would have driven most of his forces into the sea. Smith and Hill reported up the chain of command to Turner, Spruance, and Nimitz: "Issue remains in doubt." Spruance's staff began drafting plans for emergency evacuation of the landing force. The expected Japanese counterattack did not materialize. The principal dividend of all the bombardment turned out to be the destruction of Admiral Shibasaki's wire communications. The Japanese commander could not muster his men to take the offensive. A few individuals infiltrated through the Marine lines to swim out to disabled tanks and LVTs in the lagoon, where they waited for the morning. Otherwise, all was quiet.

The main struggle throughout the night of D-Day was the attempt by Shoup and Hermle to advise Julian Smith of the best place to land the reserves on D+1. Smith was amazed to learn at 0200 that Hall and Hays were in fact not ashore but still afloat at the line of departure, awaiting orders. Again, he ordered Combat Team Eight (-) to land on the eastern tip of the island, this time at 0900 on D+1. Hermle finally caught a boat to one of the destroyers in the lagoon to relay Shoup's request to the commanding general to land reinforcements on Red Beach Two. Smith altered Hall's orders accordingly, but he ordered Hermle back to the flagship, miffed at his assistant for not getting ashore and taking command. But Hermle had done Smith a good service in relaying the advice from Shoup. As much as the 8th Marines were going to bleed in the morning's assault, a landing on the eastern end of the island would have been an unmitigated catastrophe. Reconnaissance after the battle discovered those beaches to be the most intensely mined on the island.

|