| The War in the Pacific |

|

LIBERATION — Guam Remembers A Golden Salute for the 50th anniversary of the Liberation of Guam

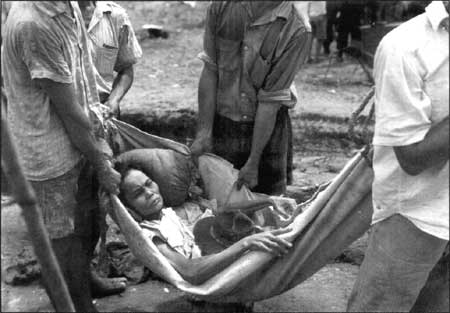

The journey to Manengon The American bombardment began on July 8, 1944, and continued until July 20. The Americans threw everything they had at the island. The continuous pounding nearly drove us insane. There was no escaping the noise. During a barrage, we couldn't speak, couldn't think. We could do nothing but wait for a lull and blessed silence. The lulls were painfully brief. As soon as our ears stopped ringing, the bombardment would begin anew. We would dive back into the shelter, muffle our ears as best we could, and cower in fear again. At the height of the bombardments, Japanese authorities ordered all civilians into designated campsites around the island. The order was issued on July 10. We learned of the order a day or two later. Once again, we packed our belongings into the bullcart ... we packed only a few items of clothing and some tools. Our main concern was our food supply. Mama had foreseen such an emergency and had stockpiled ample stores. We didn't know why we were being concentrated or how long we were to be held. We didn't know if we would survive. As usual, Mama took roll before we set out. There was Daddy, Irene, Lorraine, Bobbie, Paul, Norma, Fred, Rodney, Donald, Junie, Josephine, Michael, baby Rosamunde, me, our little Indian bull and Paul's fully loaded bullcart. We left Pado and joined other refugees on the trail. A huge throng of people was already at Tai when we arrived. The larger group had been removed from Yigo to make way for the Japanese stronghold and had been herded to Tai a day before us. Throughout the night and well into the next day, groups of people from other parts of the island arrived steadily. The Tai encampment soon turned into a sea of humanity wallowing in mud. Later that morning, the Japanese routed the encampment and the march to Manengon began. Thousands of people arose slowly from their makeshift camps and prepared to move out. Precious belongings — pathetic bundles of every size and description — were carefully lashed onto bullcarts or shouldered by their owners. Fear filled the faces of every man, woman and child. At a barked command, a column of soldiers with fixed bayonets began the march. ... The seething chaos of humans and animals compressed and uncoiled slowly, like a huge snake. Flanked by armed soldiers, the great human snake inched forward. More people joined the march when we reached the Chalan Pago crossroads. From there, we descended the steep road down to the Pago River. Just before we entered Yona, a bullcart, about two or three carts ahead of ours, broke down and halted progress. Hannah Chance Torres and her children were passengers. Like everyone else in the column, I could only watch as a soldier made his way towards Hannah's cart. He then jabbed his bayoneted rifle toward her in a threatening manner. Hannah began to scream. The soldier stormed off in disgust, but Hannah continued to shriek hysterically. ... She never recovered from the terror. Exhaustion eventually reduced her to semi consciousness. She whimpered all the way to Manengon and gave up the will to live.

The Japanese would not allow a slow, careful descent into the Manengon valley; instead, they drove everyone downward at gun point. Just before we began our descent, heavy rain began to fall again. Soon, rivulets of rainwater and mud began to wash down the slopes. Blinded by the darkness and the rain, people slipped and fell, tumbling helplessly until they slammed into rocks, trees, or other people. Men, women and children dug their feet into the mud and tried desperately to keep heavy bullcarts from careening downward out of control. In the wee hours of morning, I heard a man's voice calling out softly in the eerie silence, "Felix, Felix, mungi hao? Maila sa chachaflik si Hannah." Someone was calling Felix Torres, Hannah's husband. "Felix, Felix, where are you" the voice had said, "Come, because Hannah is dying." When we awoke at daybreak, Hannah Chance Torres was dead. Felix and his family wrapped Hannah's body in a blanket and buried her near the camp. In the days that followed, many other burials took place in and around the camp. When we first came to Manengon, the air was clean and sweet. Smoke from thousands of cooking fires would blend with the morning mist but dissipate as the day wore on. Within a few days, however, the smoke and mist began to accumulate into a thick, steamy layer above the hovels. It never dissipated. The blanket of smoke and steam sealed in all the odors in camp. As human and animal wastes piled up each day, the odors grew more and more foul. Soon, the whole camp reeked with a most horrible stench. The small stream that coursed through the valley was our only source of water. With several thousand people using it daily, it quickly turned into a cesspool. Except to conscript laborers every morning, the Japanese left us alone. Two machine gun squads were posted at the edge of the camp, but otherwise, we were free to forage in the surrounding jungle. On one particular morning, Lorraine was among several women pulled from the ranks. They were loaded onto a truck and taken from the camp. Later, we learned that they were just being used as cooks and domestics at Tai.

Among Lorraine's group was Maria Perez Howard, a pretty woman who once worked as Dad's secretary. Her husband, Edward, was a crewman on the USS Penguin and was among the American prisoners taken to Japan. Maria's good looks and her marriage to an American Navy man made her a favorite target for Japanese harassment. Just days before the American landing, Maria was led into the jungle at gunpoint. She was never seen again. Once in a while, an American plane would fly over the camp and stir up everyone's excitement. On one such occasion, my brothers and sisters and I were splashing around with some other children in a popular swimming hole not far from the camp. As we splashed in the water, the American plane appeared overhead. It circled directly above us and came in closer. It flew so low that it barely cleared the treetops. Some of the children even claimed that they saw the pilot's face. Before I could yell, "Wave and smile at him, or he'll shoot us," my companions were jumping up and down and cheering enthusiastically. When the pilot dipped his wings in acknowledgment, we got even more excited. But seconds later, our excitement turned to fear. The pilot suddenly opened fire with his machine gun. For an instant we thought the American was going to mow us down. Then suddenly, a man tore out of the machine-gunned thicket. His hands were tied behind him and he was barefoot. As he disappeared into the jungle, a Japanese patrol emerged from the thicket. I learned from my cousin, Joaquin Pangelinan, that the man was Ignacio "Kalandu" San Nicolas who had been scheduled for execution that day. The grave in the banana grove was to be his. The American pilot's machine gun fire scattered Kalandu's executioners long enough to allow his escape. I was sitting in a thicket when I began to hear a strange sound rising from the camp. I could hear people laughing and shouting and whistling. Moments later, I heard my name. It was Paul. He galloped toward me, hollering"Hurry! The Americans are here!" We ran down the hillside and into the frenzy in camp. People were laughing and crying, hugging and kissing, shouting and jumping, dancing and singing. I worked my way into the densest part of the crowd and found Dad. Together, we elbowed our way toward nine dumbfounded American soldiers. The Americans had not expected such a reception or so large a crowd. One of the soldiers was shouting and holding his rifle above the surging mob. "Follow" was all anyone heard. The word spread quickly: follow the Americans. Within a few minutes, hundreds of people fell into line and followed obediently behind the dazed Americans. The camp guards panicked and fled. From the Manengon valley, the great throng climbed into the hills and headed west. We followed paths beaten down by soldiers who had fought their way up from the Agat beachhead. When we reached the slopes above the coast, we were greeted by the incredible panorama of American military might. Agat Bay was speckled by hundreds of ships of different shapes and sizes. There were so many, they darkened the ocean all the way to the horizon. The sight was awesome. (Editor's note: This article was extracted from the late Governor Bordallo's autobiographical manuscript entitled "Uncle Sam's Mistress." Copyright 1987: R.J. Bordallo)

|