| The War in the Pacific |

|

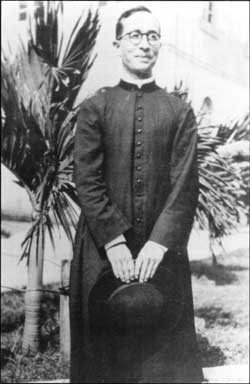

LIBERATION — Guam Remembers A Golden Salute for the 50th anniversary of the Liberation of Guam A man of courage and conviction If ever a man stood proudly for his people, the Chamorros, for his church, the Catholic Church, and for his adopted country, America, during the trying days of World War II, he was Jesus Baza Duenas. A young Catholic priest who challenged the might of the Japanese imperial forces throughout the occupation period, Father Duenas was unceremoniously executed during the darkness of night 50 years ago on July 12. Great men die young is an ancient proverb. It applies perfectly to Father Duenas, who was only 30 when Japanese forces seized Guam on that fateful day, Dec. 10, 1941. The good padre, scion of a deeply religious family, was still adjusting to his calling when the bombs fell, creating havoc and pandemonium throughout this tiny island. Almost instinctively, Father Duenas gathered some of his young followers - no doubt, acolytes at St. Joseph's Church in Inarajan - grabbed whatever weapons they could find - rifles and sidearms primarily - commandeered a small truck, and waited for the enemy. Fortunately, sober minds prevailed and Father Duenas and his small ragtag militia accepted the inevitability of a Japanese conquest.

Father Duenas was the ranking Catholic prelate in Guam at the time; the only other being Father Oscar L. Calvo, who had been ordained a priest just a few months before the war. Father Duenas could have chosen to stay in Agana, the seat of the vicariate, but instead chose to remain in the southern village of Inarajan as far away from the Japanese as possible. Early during the pacification period, the Japanese government dispatched two Catholic priests - Monsignor Fukahori and Father Peter Komatzu - to Guam to proclaim from the pulpit the greatness of the Japanese government and people. Though the monsignor presented Father Duenas with a letter from Bishop Olano - he had been sent to a prisoner-of-war camp in Kobe, Japan - naming the Chamorro priest the head of the Catholic church in Guam, Father Duenas angrily told them that they were not true men of the cloth but spies. He told them that he would have nothing to do with them, or with any other Japanese official except on matters where the welfare of his people was concerned. In a biting letter to the two Japanese priests, Father Duenas asserted: "According to a letter of Pope Benedict XV to the bishops and priests all over the world, he said 'never preach the honor and glory of your country but only the word of God.'" Duenas told them, if he should survive the war, he would have them removed from the Catholic church as clergy. Father Duenas was adamant in his refusal to cooperate with Japanese officials. During one confrontation, the fighting padre was heard to say. "I answer only to God, and the Japanese are not God." When questioned about the whereabouts of six American sailors who fled into the jungles of Guam rather than surrender, Father Duenas was quoted as saying, "It is for me to know, and for you to find out." Father Duenas was part of network of men and women who knew the movements of the American fugitives, the identities of the daring men and women who assisted and harbored them, and even the plans of Japanese search teams. He also made it a point to visit certain friends who clandestinely operated radio receivers and were well informed of the progress of war up until mid-1943, when the eventual outcome of the brutal conflict was no longer in doubt. Although Father Duenas was responsible for ministering to the needs of the people residing in the southern half of the island - Father Calvo taking care of the flock in the rest of the island - Father Duenas traveled as far north as Tamuning from time to time, thanks to "Flashy," a stallion that served him well during the occupation period. Perhaps a more important reason for the good padre to visit the north was the fact that during a six-month period in 1942, two of the six American fugitives - Al Tyson and C.B. Johnston - were hiding out in Oka, Tamuning, and Father Duenas was giving them religious instructions in anticipation of converting them to Catholicism. Father Duenas' consistent refusal to make peace with the Japanese forced the authorities to consider exiling the recalcitrant padre to the island of Rota, but Japanese authorities had to cancel such a move. They lacked evidence against Father Duenas to justify such a drastic action, and his transfer may have created more problems with the populace since the priest enjoyed high esteem throughout the island. At village meetings called by the Japanese, propagandists often emphasized that the new rulers were in Guam to save the Chamorros from the white race, and that they meant to stay for at least a hundred years. Father Duenas belittled their interpretations of events, and even at one point began humming "God Bless America."

The Japanese authorities, when it appeared that U.S. forces were soon to invade Guam, would exact their revenge on Duenas. The following is a story of the last hours of Father Duenas as told by Joaquin Limtiaco, among the few men who last saw him alive: Three days before Father Duenas and his nephew, Eddie Duenas, were beheaded, I was ordered by a Japanese official to report to Mrs. (Engracia) Butler's ranch house in Agana Heights. I had no idea why I was summoned. The Butler residence had been taken over by the Japanese who had built fortifications around the premises by this time. When I arrived - I and my family were then staying near Sinajana - I found Father Duenas, Eddie, Juan (Apu) Flores (of Inarajan), and Juan (Eto) Leon Guerrero. Father Duenas, Eddie and Eto had their hands tied behind their backs. Father Duenas and Eto were tied to the posts of a chicken shack near the residence and Eddie to a camachili tree nearby. Father Duenas was wearing a yellowish polo shirt and black trousers. Eddie also had a white polo shirt and khaki trousers. There was a nasty cut on his head and I could see blood clots around the wound. Eto, who was then 19, had been apprehended and brought to Agana Heights for building a fire while it was still dark that same morning. The boy told me later that he was cooking bread-fruit to take along with him to a Japanese work camp. I was asked by a Japanese official, through an interpreter, whether I knew Father Duenas. I said I did. He asked me whether I knew anything about a rumor that the priest was aiding American holdouts. I replied that I did not. Father Duenas was suspected of harboring Americans, either at Inarajan where he was parish priest, or some place else. He and Eddie had been taken to Agana Heights from Inarajan a few hours before my arrival. Flores was brought to the same place from Inarajan on a subsequent trip. While it was still daylight, Flores and I were ordered to gather rocks and pile them against a cave in which the Japanese planned to hide in the event of an American invasion which was just a matter of days then. At the Butler residence at the same time were two Saipanese, one was an interpreter, the other a cook. Late that night - at about midnight or 1 a.m. - the cook made some coffee, poured it into a large can, then went to sleep in the house. The few Japanese who were there had gone to sleep inside the cave. The interpreter was still in the building and I asked him whether I could offer some coffee to Father Duenas and the other two men. I told him they must be thirsty and must have smelled the boiling coffee. He said it was all right and he (the interpreter) then left for the cave to retire. I took the can of coffee, and Flores and I went to Father Duenas, who like the others, was sitting on the ground tied to the chicken shack post. We offered him the coffee and he said: "Thank you, I appreciate it." I then suggested in a whisper that we all flee from the place. I felt it was a great opportunity since none of the Japanese was awake and neither was the Saipanese interpreter and the cook. I said: "Father, Flores and I are willing, if you are, to escape from here. We can easily untie you, Eddie and Eto, and we can all flee. You know that the American bombardment has begun and it won't be long now before the invasion starts." Father replied: "No, I would rather not. The Japanese know they can't prove their charges against me. I appreciate your offer but we must also think of our families. You must know what would happen to them if we escape. I'm positive the Japanese will retaliate against them. Go and look after your own families. God will look after me. I have done no wrong. Flores and I then went to Eddie and also suggested that we escape. He replied: "I'm here with Father and I'll do whatever he wants to do. If he says we'll escape, I'm for it. If he says no, then we won't. I'm with him all the way. It's up to him." We then went back to Father Duenas and begged him again to consider our plan. He still refused. Eddie, I learned later, had been beaten up - probably in Inarajan - and his head was splattered with blood. He appeared to be in very serious condition. I believe he was clubbed before he and Father were taken to Agana Heights in a truck. Early the next morning, the three captives were still tied when Flores and I were ordered to go to Toqua (now NCS) and to bring back Antonio Artero, who was suspected of harboring (George) Tweed. If we couldn't find Antonio, we were to bring back any member of the Artero family. That was the order. Before we left, we were made to take an oath that our allegiance was to the Japanese government. We went through the formalities, of course. Father Duenas and Eddie were still tied to their respective places when Flores and I left the place. We reached Togua - we walked all the way - and found Don Pascual Artero, his son, Jose, and other members of the family, but Antonio was not around. We told them we wanted to talk to Antonio. They said he would return soon. The family had been preparing to leave their ranch and were loading a truck with things they needed for the journey. They said they expected to be summoned to Tai. When Antonio showed up, Flores and I told him we would like to talk to him alone. We moved some distance away and then we revealed our mission. I said: "Ton, you probably know why we are here. It's about Tweed. The Japanese have been informed that you are harboring him and they sent us here to take you to Agana Heights. I don't know what you plan to do. Whether they'd kill you, I don't know. But I know that the moment the Japanese see you, they'd start beating you up unmercifully. I suggest that you and your family find a good hiding place here in the jungle and wait for the Americans. The bombardment is being intensified. It won't be long now.

Mrs. Artero was so grateful that she cooked us one of the best meals we had in a long time. She cried when I told her what we had discussed with her husband. After the meal, Flores and I started on our way back to Agana Heights. We decided to tell the Japanese that we looked everywhere at the Artero ranch, from Togua to Upi, but failed to find a trace of the Arteros. The only thing we found, we decided to tell them, was a dog in one of the Artero chicken ranches. On the way down, we were given a ride by a Japanese navy truck. We had special passes which permitted us to move freely. The passes informed Japanese officials we may encounter on the way to cooperate with us. When we reached the Butler residence, we told the Japanese we could not find Artero. We made believe we were very hungry and they gave us supper - some rice and corned beef - some of the foodstuff seized from the Butlers. We looked about and noticed that Father Duenas and Eddie were not around. Eto was released and worked about the premises.

A Japanese kempetai officer later told us to leave that night for Tai and that we - Flores, Eto and I - must be there by midnight. He said Father Duenas and Eddie were taken to Tai earlier and we were to work with them in the field the following morning. Tai then was an agricultural area where local residents were made to toil in the fields. It also was the place where several local people were executed, including Juan (Mali) Pangelinan, who had hidden and fed Tweed before the Navy man went to the Arteros. On the way to Tai, we came across many Japanese civilians rushing and shouting enroute to Agana. It appeared that they were ordered to the city to battle the invading American troops. The only weapons they carried were spears and sticks. Each time we saw a group coming, we jumped into the roadside bushes. We spent the night at a ranch owned by Juan (Lala) Cruz in Chalan Pago. At about seven o'clock the next morning, we left the Cruz ranch, arriving at Tai about a half-hour later. We went to Jose Lazaro's ranch, which had been commandeered by the Japanese. There was no one around except one Japanese, a civilian who spoke Chamorro well. He was sort of a supervisor in the fields. Father Duenas and Eddie were nowhere. I asked the Japanese where the other workers were and he told me he had been in the area since 2 o'clock and that he had not seen any. The only other people there were Mr. Pedro Martinez and his late brother, Vicente, and their families. They told us they had seen no one since they arrived. It suddenly occurred to Flores and me that Father Duenas and Eddie may have already been killed, probably sometime between midnight - the time we were supposed to report there - and 2 a.m. Flores and I then proceeded to check the area, from place to place. We searched as far south as Sinajana where we entered a ranchhouse owned by Ismael Calvo. The place had been ransacked, no doubt by the Japanese. Everything was smashed. We learned later that on the night we were to report to Tai, two Guamanian men were ordered by the Japanese to dig a grave in the area where Father's and Eddie's remains were later recovered. The two diggers did not know then what the Japanese were up to. It was not until much later that the two pointed out the spot where they were told to dig. Our suspicion was confirmed when we came to Manengon later in the day. Through Juan (Ba) Duenas, we learned that Father Duenas and Eddie had been executed. Ila got the shocking news from a Saipanese relative, Joaquin Duenas, who was at Tai with the Japanese and had witnessed the killing." In early 1945, the body of the beloved priest was exhumed from a crude grave. In a later ceremony attended by hundreds of people and the island's highest officials, the body of Father Duenas was laid to rest under the altar of San Jose Church in Inarajan, the church where he had served his island flock during the occupation.

|