| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

OPENING MOVES: Marines Gear Up For War by Henry I. Shaw, Jr. The Eve of War On 1 September 1939, German armored columns and attack aircraft crossed the Polish border on a broad front and World War II began. Within days, most of Europe was deeply involved in the conflict as nations took sides for and against Germany and its leader, Adolph Hitler, according to their history, alliances, and self-interest. Soviet Russia, a natural enemy of Germany's eastward expansion, became a wary partner in Poland's quick defeat and subsequent partition in order to maintain a buffer zone against the German advance. Inevitably, however, after German successes in the west and the fall of France, Holland, and Belgium, in 1940, Hitler attacked Russia, in 1941. In the United States, a week after the fighting in Poland started, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared a limited national emergency, a move which, among other measures, authorized the recall to active duty of retired Armed Forces regulars. Even before this declaration, in keeping with the temper of the times, the President also stated that the country would remain neutral in the new European war. During the next two years, however, the United States increasingly shifted from a stance of public neutrality to one of preparation for possible war and quite open support of the beleaguered nations allied against Germany. America could not concentrate its attention on Europe alone in those eventful years, for another potential enemy dominated the Far East. In September 1940, Japan became the third member, with Germany and Italy, of the Axis powers. Japan had pursued its own program of expansion in China and elsewhere in the 1930s which directly challenged America's interests. Here too, in the Pacific arena, the neutral United States was moving toward actions, political and economic, that could lead to a clash with Japan.

In this hectic world atmosphere, America began to build its military strength. Shortly before Germany attacked Poland, at mid-year 1939, the number of active duty servicemen stood at 333,473: 188,839 in the Army, 125,202 in the Navy, and 19,432 in the Marine Corps. A year later, the overall strength was 458,365 and the number of Marines was 28,345. By early summer of 1941, the Army had 1,801,101 soldiers on active duty, many of them National Guardsmen and Reservists, but most of them men enlisted after Congress authorized a peacetime draft. The Navy, also augmented by the recall of Reservists, had 269,023 men on its active rolls. There were 54,359 Marines serving on 1 July 1941, all the Reservists available and a steadily increasing number of volunteers. Neither the Navy nor the Marine Corps had need for the draft to fill their ranks. The Marine Corps that grew in strength during 1939-41 was a Service oriented toward amphibious operations and expeditionary duty. It also had a strong commitment to the Navy beyond its amphibious/expeditionary role as it provided Marine detachments to guard naval bases and on board capital ships throughout the world. Marine aviation squadrons — all Marine pilots were naval aviators and many were carrier qualified — reinforced the Navy's air arm. Two decades of air and ground campaigns in the Caribbean and Central America, the era of the "banana wars," had ended in 1934 when the last Marines withdrew from Nicaragua, having policed the election of a new government. With their departure, enough men became available to have meaningful fleet landing exercises (FLEXs) which tested doctrine, troops, and equipment in partnership with the Navy. And the doctrine tested was both new and important. Throughout the 1920s, when Major General Commandant John A. Lejeune led the Corps, the doughty World War I commander of, briefly, the renowned 4th Marine Brigade, and then its parent 2d Infantry Division, had steadfastly emphasized the expeditionary role of Marines. Speaking to the students and faculty of the Naval War College in 1923, Lejeune said: "The maintenance, equipping, and training of its expeditionary force so it will be in instant readiness to support the Fleet in the event of War, I deem to be the most important Marine Corps duty in time of peace." But the demands of that same expeditionary duty, with Marines deployed in the Caribbean, in Central America, in the Philippines, and in China stretched the Corps thin.

Existing doctrine for amphibious operations, both in assault and defense, the focal point of wartime service by Marines, was recognized as inadequate. All sorts of deficiencies existed, in amphibious purpose, in shipping, in landing craft, in the areas of air and naval gunfire support, and particularly in the methodology and logistics of the highly complicated ship-to-shore movement of troops and their supplies once ashore. The men who succeeded Lejeune as Major General Commandant upon his retirement after two terms in office (eight years) at the Corps' helm, Wendell C. "Buck" Neville, also a wartime commander of the 4th Marine Brigade, Ben M. Fuller, who commanded a brigade in Santo Domingo during the war, and John H. Russell, Jr., a brigade commander in Haiti who then became America's High Commissioner in that country for eight years, all shared Lejeune's determination that the Marine Corps would have a meaningful role as an amphibious force trained for expeditionary use by the Navy. Each man left his own mark upon the Corps in an era of reduced appropriations and manpower as a result of the Depression that plagued the United States during their tenure. Neville, who had been awarded the Medal of Honor for his part in the fighting at Vera Cruz in 1914, unfortunately died after serving little more than a year (1929-1930) as Commandant, but his successors, Fuller (1930-1934) and Russell (1934-1936), both served to age 64, then the mandatory retirement age for senior officers. All of these Commandants, as Lejeune, were graduates of the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis and had served two years as naval cadets on board warships after graduation and before accepting commissions as Marine second lieutenants. As a consequence, their understanding of the Navy was pervasive as was their conviction that the Marine Corps and the Navy were inseparable partners in amphibious operations. In this instance, the Annapolis tie of the Navy and Marine Corps senior leaders, for virtually all admirals of the time were Naval Academy classmates, was beneficial to the Corps.

As his term as Commandant came to a close Ben Fuller was able to effect a far-reaching change that John Russell was to carry further into execution. In December 1933, with the approval of the Secretary of the Navy, Fuller redesignated the existing Marine expeditionary forces on both coasts as the Fleet Marine Force (FMF) to be a type command of the U.S. Fleet. Building on the infantrymen of the 5th Marines at Quantico and those of the 6th Marines at San Diego, two brigades came into being which were the precursors of the 1st and 2d Marine Divisions of World War II. In keeping with the times, Commandant Russell could point out the next year that he had only 3,000 Marines available to man the FMF, but the situation would improve as Marines returned from overseas stations.

The slowly building brigades and their attendant squadrons of Marine aircraft, the only American troops with combat and expeditionary experience beyond the trenches and battlefields of France, came into being in a climate of change from the "old ways" of performing their mission. At the Marine base at Quantico, Virginia, also the home of advanced officer training for the Corps, a profound event had taken place in November 1933 that would alter the course of the war to come. That month, all classes of the Marine Corps Schools were suspended and the students and faculty, including a sprinkling of Navy officers, were directed to concentrate their efforts on developing a detailed manual which would provide the guidance for the conduct of amphibious operations. The decision was not purely a Marine Corps one, since Quantico and the staff of the Naval War College at Newport, Rhode Island, had been exchanging ideas on the subject for more than a decade. All naval planners knew that the execution of the contingency operations they envisioned worldwide would be flawed if the United States did not have adequate transport and cargo shipping, appropriate and sufficient landing craft, or trained amphibious assault troops. But the Quantico working group, headed by Colonel Ellis B. Miller, proceeded on the assumption that all these would be forthcoming. They developed operating theories based on their experience and their hopes which could be refined by practice. They formulated answers to thorny questions of command relationships, they looked at naval gun fire and air support problems and provided solutions, they addressed the ship-to-shore movement of troops and developed unloading, boat control, and landing procedures, and they decided on beach party and shore party methods to control the unloading of supplies on the beaches. In January 1934, a truly seminal document in the history of amphibious warfare was completed and the "Tentative Manual for Landing Operations" was published by the Marine Corps. In the years that followed, as fleet landing exercises re fined procedures, as the hoped-for improved shipping and landing craft gradually appeared, and as increasing numbers of seamen and assault troops were trained in amphibious landing techniques, the Quantico manual was reworked and expanded, but its core of innovative thinking remained. In 1938 the Navy promulgated the evolved manual as Fleet Training Publication (FTP) 167; it became the bible for the conduct of American amphibious operations in World War II. In 1941 the Army published FTP-167 as Field Manual 31-5 to guide its growing force of soldiers, most of whom would train for and take part in amphibious operations completely unaware of the Marine Corps influence on their activities. Truly, the handful of Marine and Navy officers at Quantico in 1933-34 had revolutionized the conduct of amphibious warfare.

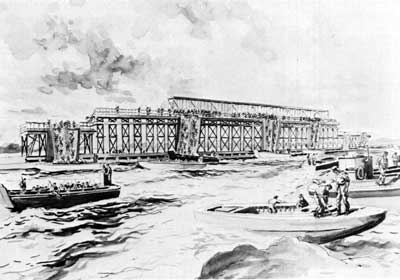

Despite the fiscal constraints of the Depression, the number and variety of naval ships devoted to amphibious purposes gradually increased in the 1930s. As the threat of American involvement in the war also grew stronger, vastly increased funds were made available for the Navy, the country's "first line of defense," and specialized transport and cargo ships appeared. These were tested and modified and became an increasing factor in the FLEXs which took place every year from 1935 on, usually with practice landings at Culebra and Vieques Islands off Puerto Rico in the Atlantic Ocean, at San Clemente Island off the southern California coast, and in the Hawaiian Islands. While the number of "big" amphibious ships, transports and cargo vessels, slowly grew in number, the small boat Navy of amphibious landing craft similarly evolved and increased. They were vital to the success of landing operations, a means to get assault troops ashore swiftly and surely. For most Marines of the era, there are memories of ships' launches, lighters, and experimental boats of all sorts that brought them to the beach, or at least to the first sandbar or reef offshore. Rolling over the side of a boat and wading through the surf was a common experience. One future Commandant, then a lieutenant, recalled making a practice landing on Maui in the Hawaiian Islands as his unit returned from expeditionary duty in China in 1938. He described the landing as "one of those old timers" made in "these damned motor launches, you know, with a prow and everything — never made for a landing." The result, he said in colorful memory, was "you grounded out somewhere 50 yards from the beach and jumped in. Sometimes your hat floated and sometimes you made it." The landing craft that changed this picture was the Higgins boat, named after its inventor, Andrew Higgins, who developed a boat of shallow draft that could reach the beach in three to four feet of water, land an infantry platoon, and then retract to return for another load. First used on an experimental basis in FLEX 5 (1938) at Culebra, it won its way over rivals and was adopted as the standard personnel landing craft by 1940. In its initial hundreds the Higgins boat had a sloping bow that required of its passengers an over-the-side agility after it grounded. In 1941, a version, most familiar to World War II veterans, was introduced which had a bow ramp which allowed men and vehicles to exit onto a beach or at least into knee-high, not neck-high water. This was the 36-foot Landing Craft, Vehicle and Personnel (LCVP) which was fitted to the boat davits on every amphibious transport and cargo vessel. Its companion boat, the 50-foot, ramped Landing Craft, Mechanized (LCM), also a development of Andrew Higgins, provided the means for landing tanks, artillery, and heavy vehicles.

The variety of landing craft that eventually evolved, and the tasks to which they were put, was limited only by the ingenuity of those who planned their uses and the seamanship of the sailors who manned them. But for most prewar Marines, the memories of practice landings featured the rampless Higgins boat, various tank lighters which made each beach approach an adventure, and all sorts of "make do" craft of earlier years which were ill suited for surf or heavy seas.

One amphibious craft development of the prewar years, equal in its impact on amphibious landings to the LCVP and the LCM, was the tracked landing vehicle, the LVT. Developed in the late 1930s by Donald Roebling for use as a rescue vehicle in the Florida everglades, the LVT, or the Alligator as it was soon popularly named, could travel over land or water using its cupped treads for propulsion. The stories of the "discovery" of Roebling's invention and of its subsequent testing and development are legion. It proved to have an invaluable capability, not considered in its initial concept; it could cross coral reefs, and coral reefs fringed the beaches of most Pacific islands. The amphibian tractor, or amtrac to its users, was a natural weapon for Marines and there was hardly a whisper of opposition to its adoption. When the first production LVTs rolled off Roebling's assembly line at his plant at Clearwater, Florida, in July 1941, there was already a detachment of Marines at nearby Dunedin learning to drive and maintain the new tractors and to develop tactics for their effective use. In the new Marine divisions then forming on each coast there would be a place for an amtrac battalion. The LVTs were conceived at first as a logistics vehicle, a means to carry troops and supplies onto and inshore of difficult beaches. But no sooner did the LVTs make their appearance in significant numbers than the thought occurred that the tractors could be armed and that they could have a role as an assault vehicle, leading assault waves. Innovations in amphibious shipping and landing craft in the late 30s and early 40s were not solely based on American concepts. With the exception of the LVT, most amphibious craft developments and certainly amphibious shipping developments were influenced by British concepts, requirements, and experience. Although officially neutral in the fighting at sea in the Atlantic and ashore in Europe, the United States was in fact deeply involved in supporting the embattled British. For a long period in 1940-41, the Marine Corps was concerned in this effort, and to the troops in training, particularly those on the east coast, there was a real question whether they might leave their bases for Europe or the Pacific. Marine pilots had a definite fascination with the exploits of the Royal Air Force in its battles with the German Luftwaffe.

|