| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

OPENING MOVES: Marines Gear Up For War by Henry I. Shaw, Jr. Atlantic Theater Because the British had fought the Germans since 1939, their combat know-how and experience in air, land, and sea battles were invaluable to the American military. A steady stream of American observers, largely unheralded to the public, visited Britain and British and Allied forces in the field during 1940-41 to learn what they could of such new warfare innovations as radar, pioneered by the British; to see how antiaircraft defenses were operating; to learn what constant air raids and battles could teach; and to see how Britain's land forces were preparing for their eventual return to Europe. The Marine Corps Commandant, Major General Thomas Holcomb, made sure that his officers played a strong part in this learning process from the British. Holcomb, who had ably commanded a battalion of the 6th Marines in the fighting in France in 1918, had initially been appointed Commandant by President Roosevelt on 1 December 1936. After serving with distinction through the European outbreak of World War II and the Corps' initial war-related buildup, he was reappointed Major General Commandant by the President for a second four-year term on 1 December 1940. The Commandant, besides being a dedicated Marine who championed the Corps during trying times, was also an astute player of the Washington game. A respected colleague and friend of the admirals who commanded the Navy, Holcomb was equally at ease and a friend to the politicians who controlled the military budget. He understood the President's determination to see Great Britain survive, as well as his admiration of the British peoples' struggle. Always well aware of the value of the public image of the Marine Corps as a force "first to fight." Holcomb at times yielded to pressures to experiment with new concepts and authorize new types of organizations which would enhance that image. The Marines whom he sent to Great Britain were imbued with the desire to gain knowledge and experience that would help the Corps get ready for the war they felt sure was coming. The British, who shared the view that the Americans would eventually enter the war on their side, were open and forthcoming in their cooperation.

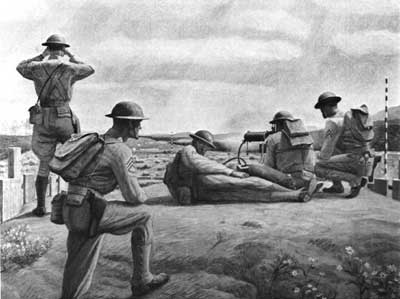

In 1941 particularly, the Marine observers, ranging in rank from captains to colonels, visited British air stations and air control centers, antiaircraft command complexes and firing battery sites, and all kinds of troop formations. The weapons and equipment being used and the tactics and techniques being practiced were all of interest. Much of what was seen and reported on was of immediate value to the Americans and saw enhanced development in the States. On the air side, briefings on radar developments were invaluable, as were demonstrations of ground control intercept practices for night fighters and the use of night fighters themselves. Anything the British had learned on air defense control and antiaircraft usage was eagerly absorbed. The Marine air observers would note on their return that they had dealt with numbers of aircraft and concepts of command and control that were not remotely like Marine Corps reality, but all knew that these numbers of aircraft and their control equipment were authorized, funded, and building. The fascination of the time, although focused on the Battle of Britain's aerial defenses, was not only with the air war but also with the "elite" troops, the sea-raiding commandos, as well as the glider and parachute forces so ably exploited by the Germans in combat and now a prominent part of Britain's army. The role of the commandos, who were then Army troops but who eventually would be drawn exclusively from Royal Marines ranks, raised a natural favorable response in the American Marines. Most of the observers were enthusiastic about the commando potential, but at least one U.S. Marine senior colonel, Julian C. Smith, who watched commando exercises at Inverary, Scotland, was not overly impressed. Smith, who later commanded the 2d Marine Division at the epic battle for Tarawa, told General Holcomb that the commandos "weren't any better than we; that any battalion of Marines could do the job they do." For the moment at least, Smith's view was a minority evaluation, one not shared, for instance, by commando enthusiast President Roosevelt, and the Marine Corps would see the raising of raider battalions to perform commando-like missions. In similar fashion, and for much the same reasons, Service enthusiasm for being at the cutting edge and popular acclaim of elite formations, the Marine Corps raised parachute battalions, glider squadrons, and barrage balloon squadrons, all of which were disbanded eventually in the face of the realities of the island-dominated Pacific theater. They might have served their purpose well in Europe or North Africa but the Marine Corps' destiny was in the Pacific. Marines of the pre-Pearl Harbor Corps, filled with memories of their later battles with the Japanese, are sometimes prone to forget that Germany was as much their potential enemy in 1940-41 as Japan. At the time, many must have felt as did one artillery lieutenant and later raider officer who took part in fleet exercises of early 1941 that "we all cut our teeth on amphibious operations, actually not knowing whether we were going to leave Guantanamo for Europe or the Pacific." What the Marines at Guantanamo Bay did know was that their Cuban base was bustling with men as mobilized Reservists and new recruits joined. And as the necessary men came in, the brigade grew in size and abounded with changes of organizations and activations.

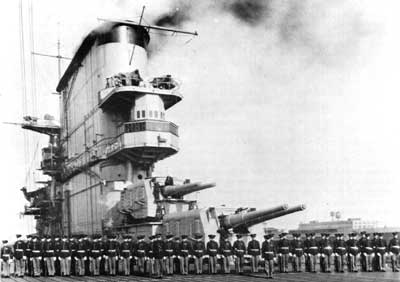

The 1st Marine Brigade, at first essentially one infantry regiment, the 5th Marines, one artillery battalion, the 1st Battalion, 11th Marines, and supporting troops, had moved to Guantanamo from Quantico in the late fall of 1940 as its FMF units had outgrown the Virginia base. At "Gitmo," as it was known to all, the brigade's units became the source of all new organizations. Essentially, existing outfits, from battalions through platoons, were split in half. To insure a equal distribution of talent as well as numbers, the brigade commander, Brigadier General Holland M. "Howling Mad" Smith, shrewdly had each unit commander turn in two equallists, leaving off the commanding officer (CO) and his executive officer. As a later combat battalion commander of the 5th recalled the process, when redesignation took place, "the CO would command one unit, one former exec would become CO of the other.... But until the split was made and the redesignation announced, no CO could know which half he would command. In this manner, the 5th Marines gave birth to the 7th Marines and the 1st Battalion, 11th Marines to the 2d Battalion. Not too long after, all the units of the 5th, 7th, and 11th Marines and their supporting elements were again split, this time into three equal lists, leaving out the three senior men. A new regiment, the 1st Marines with its necessary support, was formed equitably from the 5th and 7th, because the COs of the older units did not know whether they would stay behind (two lists) or take over the new outfits. On 1 February 1941, the 1st Marine Brigade was redesignated the 1st Marine Division while its troops were on board ship heading for the Puerto Rican island of Culebra for maneuvers. At the same time on the west coast, the 2d Brigade, at San Diego, which had grown in a similar fashion from its original infantry regiment, the 6th Marines, was redesignated the 2d Marine Division. Most of its troops, however, were located at a new FMF base, Camp Elliott, in the low, hilly country 12 miles northeast of San Diego. At Marine Corps headquarters, it was readily apparent that the planned expansion of the Corps to an FMF strength of at least two infantry divisions and two supporting air craft wings would require a vastly increased supporting establishment. Not least among the new requirements for manpower and equipment were those for a new species of units, defense battalions, which were projected to garrison forward bases, including Guantanamo and key American holdings in the Pacific. Also a drawdown on Marine resources was the need to provide guard detachments for many new naval bases and Navy capital ships which were being rushed to completion. The surging demand for men was matched by equal demand for training facilities. What occurred then in late 1940 and early 1941 was a thorough search by Marines of the east and west coasts of the United States for base sites suitable for training one or more divisions whose main mission was amphibious warfare. Extensive combat exercise areas with direct access to the ocean were required. At the same time, there was a parallel need for suitable airfield locations near the proposed amphibious training sites which would house the planned for but not yet existing squadrons and groups of one or more air wings, each with hundreds of fighter, scout-bomber, torpedo-bomber, and utility aircraft. When the first divisions and wings moved out to combat, the new bases were projected to be training bases for reinforcing and replacement organizations.

Camp Elliott and a group of smaller supporting camps which grew up in its shadow in 1941 were barely adequate to house the growing FMF ground establishment on the west coast. The naval air stations in the San Diego area could still handle the limited number of aircraft available. The same situation was not true of the three major Marine bases in the east. While Quantico's air station could accommodate the planes of Marine Aircraft Group 1, the main base itself was keyed to support specialist and officer training and was not suitable for extensive FMF operations. Swamp-bound Parris Island teemed with recruits and had no room for the FMF. The newly developed outlying camp at nearby Hilton Head Island was reserved for essential defense battalion training. The treaty-restricted area of the naval base at Guantanamo had no room for a reinforced division's 20,000 men. Congress authorized the construction of a vast, new Marine base in coastal North Carolina on 15 February 1941. It was, in a sense, a remote area that had been picked, certainly not one near any center of population. The Commandant, writing to a fellow general, commented "those who want to be near big cities will be disappointed because it is certainly out in the sticks," noting however, that it was a great place for maneuvers and amphibious landings. The chosen spot located in the New River area of Onslow County, was described by the 1st Division's World War II historian as "111,170 acres of water, coastal swamp, and plain, theretofore inhabited largely by sand flies, ticks, chiggers, and snakes." And he might have added covered by pine forest and scrub growth. One of the Marine veterans of the Nicaraguan jungle campaigns said: "Actually, Nicaragua was a much pleasanter place to live than the New River area at the time. They had mosquitoes there with snow on the ground." Despite its perceived faults, the die was cast for New River and construction of a huge tent camp was begun there in April with a projected readiness date of early summer. The famed brick barracks that were a feature of what would become Camp Lejeune were on the architect's drawing boards when Marine Barracks, New River, North Carolina, was activated on the 1st of May.

The 1st Division soon became acquainted with the place that one regimental commander noted was "the only place between Biloxi, Mississippi, and the New Jersey capes where you could make a landing with two divisions abreast." Coming from Guantanamo, the division spent the summer of 1941 landing across Onslow Beach and moving inland through the swamps and pine barrens. By that time, Tent Camp or "Tent City" was ready to receive its new tenants. Strange as it might seem, these 1st Division Marines reveled in their austere setting amidst the stifling heat. They were already contrasting themselves to those on the west coast, derisively labelled "Hollywood Marines," because some units had appeared briefly in movies being shot at the time. There was a feeling, obviously not shared by those in the west, that Parris Island and New River somehow were the most rugged places to endure, in contrast to those who were close to "civilization." The new Marine airfield, which was to become an integral part of the North Carolina training complex, was formally established on 18 August 1941 when the administrative office for the new "Air Facilities under Development" was established at New Bern, about 40 miles north of New River. Construction there proceeded at the same frenetic pace that marked the development of the ground training center. In September, the administrators moved to the actual airfield site nearby, Cherry Point, and on 1 December Marine Corps Air Station, Cherry Point, was activated. Most of the planes on the east coast were still at Quantico, but a great start had been made on what became in short order the center of a network of training fields which would house enough squadrons and air groups to feed most of the augmentation and replacement demands of four aircraft wings overseas. The actual establishment of the initial wing commands took place at Quantico (1st Marine Aircraft Wing [MAW]) on 7 July 1941 and San Diego (2d MAW) on 10 July. Initially, each wing could count on only one air group as its main strength, Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 11 in the east and MAG-21 in the west. The vast increase of aircraft and aviation personnel that marked the growth of Marine aviation in World War II was in the works. The pilots, aircrewmen, and mechanics were training at Navy air facilities and the planes were coming off assembly lines in steadily in creasing numbers. It was August 1942, however, before the impact of the air buildup would be fully felt at Guadalcanal. As an all-volunteer force, the Marine Corps was fully deployable during this training and preparedness period. In a sense, the Army was hampered in its readiness by the fact that its draftees, which soon composed the bulk of its strength, could not be sent outside the U.S. without a declaration of war. As a result, when the seizure of the French island of Martinique was contemplated in 1940, the planned assault force was the 1st Marine Brigade. When the perceived threat of a garrison in the Caribbean loyal to Vichy France lessened, other overseas expeditions were also contemplated. In the spring of 1941, the Portuguese Azores became the projected target for an amphibious seizure because it was believed that the Germans might take the strategic islands and thereby seriously threaten the sea lanes of commerce and replenishment for British and Allied bases in the home islands, Africa, and the Mediterranean. Again, Marines were to be in the forefront of the landing force and, again, when the perceived threat lessened, the operation was called off.

The buildup of forces for the potential Azores campaign did have a profound effect on the Marine Corps, however, despite its cancellation. The core regimental combat team of the 2d Division, the 6th Marines and its supporting units, judged the most ready for active employment, loaded out from San Diego in May 1941 to sail through the Panama Canal and augment the Marine troops on the east coast. Enroute, the Azores objective disappeared and another took its place, Iceland. The strategic island in the middle of the North Atlantic had been occupied by British troops to forestall a similar German move. The British wanted their Iceland occupation troops back in the United Kingdom and asked for Americans to take their place. When President Roosevelt made the decision to comply with the British request, seeing the move as vital to protecting sea traffic from German raiders, the 6th Marines was at sea and, all unwitting, became the choice for the first American troops to deploy. When the regiment's troop ships reached Charleston, South Carolina, after the Panama passage, the 6th Marines was joined by the 5th Defense Battalion from Parris Island. A new unit, the 1st Marine Brigade (Provisional), was activated. When the ships began to load massive amounts of supplies, including winter protective gear and clothing, the favorite rumor of the Marines, that they were headed to a warm and sunny clime, was effectively scotched. The convoy left Charleston soon after and on 7 July 1941 made landfall at Iceland. For nine months thereafter, one of the precious few trained Marine infantry regiments was in garrison in Iceland, and the 2d Division was short a vital element of its strength. The sudden and un expected deployment of the 6th Marines to the Atlantic was to have a considerable effect on the employment of Marine ground forces in the days after Pearl Harbor. The drawdown on Marine strength represented by the departure of 5,000 men to Iceland was but a part of the drain of manpower that came about as a result of the fact that Marines could be sent anywhere at any time. In his zeal to support the British in ways short of war, and to enhance American hemispheric defenses, the President in mid-1940 had authorized a swap of 50 average American destroyers of World War I vintage to Britain in return for 99-year leases to bases at British Atlantic possessions. These bases were all naval and naval bases required Marine guards. As a result, a senior Marine colonel, Omar T. Pfeiffer, was made a member and recorder of a board of naval officers, the Greenslade Board, that surveyed the British locations in the late summer of 1940 to recommend appropriate American base strength and facilities. Flown first to Bermuda, the board members moved on by air to Argentina, Newfoundland, and Nassau in the Bahamas, and from there touched down at Guantanamo where they boarded the cruiser St. Louis for the rest of their journey. Sailing to Kingston, Jamaica; Port-of-Spain, Trinidad; and Georgetown, British Guyana, the board then checked the islands of Tobago, St. Lucia, and Antigua. At each of these places, it was determined that a Marine guard detachment was needed and 50-to-100-man companies were activated for that purpose in January 1941 so that the Marines could guard the facilities as they were built. It was not bad duty for the men involved, but their deployment meant a battalion less of Marines for the FMF. Colonel Pfeiffer was a participant in British-American discussions of possible measures to be taken in the event of war with Germany and Japan (the Rainbow Plan) which took place in Washington in 1940 and 1941. In April 1941 he was posted to a new position as Fleet Marine Officer of the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor which drew fully on his expertise and experience. Despite the possible and actual overseas deployments of Marines in the Atlantic Theater throughout 1941, the weight of Marine commitment was in the Pacific. And there was no question of the potential enemy there. It was Japan.

|