| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

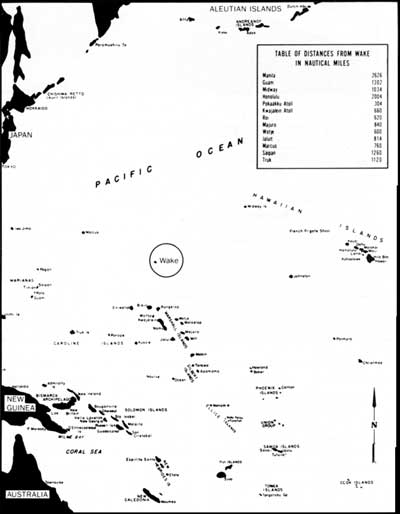

A MAGNIFICENT FIGHT: Marines in the Battle for Wake Island by Robert J. Cressman It is Monday, 8 December 1941. On wake Island, a tiny sprung paper-clip in the Pacific between Hawaii and Guam, Marines of the 1st Defense Battalion are starting another day of the backbreaking war preparations that have gone on for weeks. Out in the triangular lagoon formed by the islets of Peale, Wake, and Wilkes, the huge silver Pan American Airways Philippine Clipper flying boat roars off the water bound for Guam. The trans-Pacific flight will not be completed. Word of war comes around 0700. Captain Henry S. Wilson, Army Signal Corps, on the island to support the flight ferry of B-17 Flying Fortresses from Hawaii to the Philippines, half runs, half walks toward the tent of Major James P.S. Devereux, commander of the battalion's Wake Detachment. Captain Wilson reports that Hickam Field in Hawaii has been raided.

Devereux immediately orders a "Call to Arms." He quickly assembles his officers, tells them that war has come, that the Japanese have attacked Oahu, and that Wake "could expect the same thing in a very short time."

Meanwhile, the senior officer on the atoll, Commander Winfred S. Cunningham, Officer in Charge, Naval Activities, Wake, learned of the Japanese surprise attack as he was leaving the mess hall at the contractors' cantonment (Camp 2) on the northern leg of Wake. He ordered the defense battalion to battle stations, but allowed the civilians to go on with their work, figuring that their duties at sites around the atoll provided good dispersion. He then contacted John B. Cooke, PanAm's airport manager and requested that he recall the Philippine Clipper. Cooke sent the prearranged code telling John H. Hamilton, the captain of the Martin 130 flying boat, of the outbreak of war.

Marines from Camp 1, on the southern leg of Wake, were soon embarked in trucks and moving to their stations on Wake, Wilkes, and Peale islets. Marine Gunner Harold C. Borth and Sergeant James W. Hall climbed to the top of the camp's water tower and manned the observation post there. In those early days radar was new and not even set up on Wake, so early warning was dependent on keen eyesight. Hearing might have contributed elsewhere, but on the atoll the thunder of nearby surf masked the sound of aircraft engines until they were nearly overhead. Marine Gunner John Hamas, the Wake Detachment's munitions officer, unpacked Browning automatic rifles, Springfield '03 rifles, and ammunition for issue to the civilians who had volunteered for combat duty. That task completed, Hamas and a working party picked up 75 cases of hand grenades for delivery around the islets. Soon thereafter, other civilians attached themselves to marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 211, which had been on Wake since 4 December.

Offshore, neither Triton (SS-201) nor Tambor (SS-198), submarines that had been patrolling offshore since 25 November, knew of developments on Wake or Oahu. They both had been submerged when word was passed and thus out of radio communication with Pearl Harbor. The transport William Ward Burrows (AP-6), which had left Oahu bound for Wake on 27 November, learned of the Japanese attack on Pearl while she was still 425 miles from her destination. She was rerouted to Johnston Island. Major Paul A. Putnam, VMF-211's commanding officer, and Second Lieutenant Henry G. Webb had conducted the dawn aerial patrol and landed by the time the squadron's radiomen, over at Wake's airfield, had picked up word of an attack on Pearl Harbor. Putnam immediately sent a runner to tell his executive officer, Captain Henry T. Elrod, to disperse planes and men and keep all aircraft ready for flight.

Meanwhile, work began on dugout plane shelters. Putnam placed VMF-211 on a war footing immediately; two two-plane sections then took off on patrol. Captain Elrod and Second Lieutenant Carl R. Davidson flew north, Second Lieutenant John F. Kinney and Technical Sergeant William J. Hamilton flew to the south-southwest at 13,000 feet. Both sections were to remain in the immediate vicinity of the island.

The Philippine Clipper, meanwhile, had wheeled about upon receipt of word of war and returned to the lagoon it had departed 20 minutes earlier. Cunningham immediately requested Captain Hamilton to carry out a scouting flight. The Clipper was unloaded and refueled with sufficient gasoline in addition to the standard reserve for both the patrol flight and a flight to Midway. Cunningham, an experienced aviator, laid out a plan, giving the flying boat a two-plane escort. Hamilton then telephoned Putnam and concluded the arrangements for the search. Take-off time was 1300.

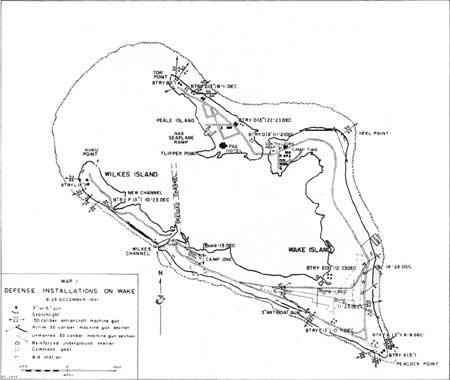

Shortly after receiving word of hostilities, Battery B's First Lieutenant Woodrow M. Kessler and his men had loaded a truck with equipment and small arms ammunition and moved out to their 5-inch guns. At 0710, Kessler began distributing gear, and soon thereafter established a sentry post on Toki Point at the northermost tip of Peale. Thirty 5-inch rounds went into the ready-use boxes near the guns. At 0800, re reported his battery ready for action. General quarters called Captain Bryghte D. "Dan" Godbold's men of Battery D to their stations down the coast from Battery B at 0700, and they moved out to their position by truck, reporting "manned and ready" within a half hour. The lack of men, however, prevented Godbold from having more than three of his 3-inch guns in operation. Within another hour and a half, each gun had 50 rounds ready for firing. At 1000, Goldbold received orders to keep one gun, the director, the heightfinder (the only one at Wake Island for the three batteries), and the power plant manned at all times. After making those arrangements, Godbold put the remainder of his men to work improving the battery position. While the atoll's defenders prepared for war, Japanese bombers droned toward them. At 0710 on 8 December, 34 Mitsubishi G3M2 Type 96 land attack planes (Nells) of the Chitose Air Group had lifted off from the airstrip at Roi in the Marshalls. Shortly before noon, those 34 Nells came in on Wake at 13,000 feet. Clouds cloaked their approach and the pounding surf drowned out the noise of their engines as they dropped down to 1,500 feet and roared in from the sea. Lookouts sounded the alarms as they spotted the twin-engined, twin-tailed bombers a few hundred yards off the atoll's south shore, emerging from a dense bank of clouds. At Battery E, First Lieutenant Lewis telephoned Major Devereux's command post to inform him of the approaching planes. Although Putnam was rushing work on the six bunkers being built along the seaward side of the runway, he knew none of them would be ready before 1400. He also knew that moving the eight F4F Wildcats from their parking area would risk damage to the planes and obstruction of the runway if the planes were in fact damaged. Since any damage might have meant the loss of a plane—Wake possessed virtually no spare parts—Putnam decided to delay moving the Wildcats and the material until suitable places existed to protect them. No foxholes had been dug near the field, but the rough ground nearby offered natural cover to those who reached it. Putnam hoped that his men would obtain good cover if an attack came. The movement of gasoline, bombs, and ammunitions; then installation of electrical lines and generators; and the relocation of radio facilities kept all hands busily engaged. The attack found Second Lieutenant Robert "J" Conderman and First Lieutenant George A. Graves in the ready tent, going over last minute instructions concerning their escort of the Philippine Clipper. When the alarm sounded, both pilots, already in flight gear, sprinted for their Wildcats. Graves managed to reach one F4F, but a direct hit demolished it in a ball of flame as he was climbing into the cockpit, killing him instantly. Strafers' bullets cut down Conderman, as he tried to reach his plane, and as he lay on the ground a bomb hit the waiting Wildcat and blew it up, pinning him beneath the wreckage. He called to Corporal Robert E.L. Page to help him, but stopped when he heard another man crying for help. He directed Page to help the other man first. Strafing attacks killed Second Lieutenant Frank J. Holden as he raced for cover. Bullets and fragments wounded Second Lieutenant Webb. Marine Gunner Hamas, who still had 50 cases of hand grenades in his truck, having just delivered 25 to Kuku Point, saw the red sun insignia on the planes as they roared low overhead. Immediately, he ordered the vehicle stopped and instructed his men to head for cover. Confident that his airborne planes would be able to provide sufficient warning of an incoming raid, Commander Cunningham was working in his office at Camp 2, when he heard the "crump" of bombs around 1155. The explosions rattled windows elsewhere in the camp, prompting many men to conclude that work crews were blasting coral heads in the lagoon.

Guns 1 and 2 of Battery D opened up on the attackers, collectively firing 40 rounds during the raid. The low visibility and the altitude at which the Mitsubishis flew, however, prevented the 3-inch guns from firing effectively. No bombs fell near the battery, but the guns' own concussions caved in the sandbag emplacements. Marine antiaircraft fire damaged eight Nells and filled a petty officer in one of them. Returning Japanese aircrews claimed to have set fire to all of the aircraft on the ground, and reported sighting only three airborne American planes. On Peacock Point, First Lieutenant Lewis' Battery E had been standing-to, ready to fire. Like Godbold, Lewis did not have enough men for all four of his guns. Lewis manned two of the 3-inchers, along with the M-4 director, while the rest of his men busily completed sandbag emplacement. After telephoning Devereux's command post when he saw the falling bombs. Lewis quickly estimated the altitude and ordered his gunners to open fire. Again, however, the height at which the attackers came rendered the fire ineffective. In about seven minutes, Japanese bombs and bullets totally wrecked PanAm's facilities. Bombing and strafing set fire to a hotel—in which five Chamorro employees died—and also to a stock room, fuel tanks, and many other buildings, and demolished a radio transmitter. Nine of PanAm's 66-man staff lay dead. Two of the Philippine Clipper's crew were wounded.

Almost miraculously, though, the 26-ton Clipper, empty of both passengers and cargo but full of fuel, rode easily at her moorings at the end of the dock. A bomb had splashed 100 feet ahead of her without damaging her, and she received 23 bullet holes from the strafing attack—none had hit her large fuel tanks. Captain Hamilton courageously proposed evacuating the passengers and PanAm staff and Commander Cunningham assented. Stripped of all superfluous equipment and having embarked all of the passengers and the Caucasian PanAm employees, save one (who had been driving the atoll's only ambulance and thus had not heard the call to report for the plane's departure), the flying boat took off for Midway at 1330. Although he had received a bullet wound in his left shoulder, Major Putnam immediately took over the terrible task of seeing to the many injured people at the field. His dedication to duty seemed to establish the precedent for many other instances of selflessness which occurred amidst the wreckage of the VMF-211 camp. Sadly, the attack left five pilots and 10 enlisted men of VMF-211 wounded and 18 more dead, including most of the mechanics assigned to the squadron. On the materiel side, the squadron's tents were shot up and virtually no supplies—tools, spark plugs, tires, and sparse spare parts—escaped destruction. Both of the 25,000-gallon gasoline storage tanks had been demolished. Additionally 25 civilian workmen had been killed. As the bombers departed, Gunner Hamas called his men back from the bush, and set out to resume delivery of hand grenades. As he neared the airfield, though, he stopped to help wounded men board a truck that had escaped destruction. Then, he continued his journey and finally returned to Camp 1, where he found more civilian employees arriving to join the military effort. Earlier, as they had returned to the vicinity of Wake at about noon, Kinney and Hamilton had been descending through the broken clouds about three miles from the atoll when the former spotted two formations of planes at an elevation of about 1,500 feet. He and Hamilton attempted unsuccessfully to catch the formations as they retired to the west through the overcast. Kinney and Hamilton remained aloft until after 1230, when they landed to find the destruction that defied description. Neither Elrod nor Davidson had seen the enemy.

In the wake of the terrible devastation wreaked upon his squadron, Putnam deemed it critical to the squadron's reorganization to keep the remaining planes operations. Since his engineering officer, Graves, Had been killed, Putnam appointed Kinney to take his place. "We have four planes left," Putnam told him, "If you can keep them flying I'll see that you get a medal as big as a pie." "Okay, sir," Kinney responded, "if it is delivered in San Francisco." Putnam established VMF-211's command post near the operations area. His men dug foxholes amidst brush and all of the physically capable officers and men stayed at the field. Putnam ordered that pistols, Thompson submachine guns, gas masks, and steel helmets be issued, and also directed that machine gun posts be established near each end of the runway and the command post. Meanwhile, the ground crews dispersed the serviceable planes into revetments, a task not without its risks. That afternoon, Captain Frank C. Tharin accidentally taxied 211-F-9 into an oil drum and ruined the propeller, reducing the serviceable planes to three. Captains Elrod and Tharin (the latter wounded superficially in the attack) later supervised efforts to construct "protective works" and also the mining of the landing strip with dynamite connected up to electric generators. Contractors bulldozed portions of the land bordering the field, in hopes that the rough ground would wreck and enemy planes that attempted to land there. That afternoon, over at Battery D, Godbold's men repaired damaged emplacements, improved the director position, and accepted delivery of gas masks, hand grenades, and ammunition. Later that afternoon, 18 civilians reported for military duty. Godbold assigned 16 of them to serve under Sergeant Walter A. Bowsher, Jr., to man the previously idle Gun 3, and assigned the remaining pair to the director crew as lookouts. Under Bowsher's leadership, the men in Gun 3 were soon working their piece "in a manner comparable to the Marine-manned guns." Gunner Hamas and his men, meanwhile, carted ammunition from the quartermaster shed and dispersed it into caches, each of about 20 to 25 boxes, west of Camp 1, near Wilkes Channel, and camouflaged them with coral sand. Next, they dispersed hundreds of boxes of .5— and .30-caliber ammunition in the bushes that lined the road that led to the airfield. Before nightfall, Hamas delivered .50-caliber ammunition and metal links to Captain Herbert C . Freuler and furnished him the keys to the bomb and ammunition magazines. About 25 civilians with trucks responded to First Lieutenant Lewis' request for assistance in improving his battery's defensive position. Then, Lewis ordered his men to lay a telephone line from the battery command post (CP) to the battery's heightfinder so that he could obtain altitude readings for the incoming enemy bombers, and relay that information to the guns. Commander Campbell Keene, Commander, Wake Base Detachment, meanwhile, reassigned his men to more critical combat duties. He sent Ensigns George E. Henshaw and Bernard J. Lauff to Cunningham's staff. Boatswain's Mate First Class James E. Barnes and 12 enlisted men joined the ranks of the defense battalion to drive trucks, serve in galley details, and stand security watches. One of the three enlisted men whom Commander Keene sent to VMF-211 was Aviation Machinist's Mate First Class James F. Lesson. Kinney and Technical Sergeant Hamilton soon found the Pennsylvanian with light brown hair, who had served in the Air Corps before he had joined the Navy and who had just turned 35 years of age, to be invaluable. VMF-211 also benefited from the services of civilians Harry Yeager and "Doc" Stevenson, who reported to work as mechanics, and Pete Sorenson, who volunteered to drive a truck. For the remainder of the day and on into the night, in the contractor's hospital in Camp 2, Naval Reserve Lieutenant Gustave M. Kahn, Medical Corps, and the contractors' physician, Dr. Lawton E. Shank, worked diligently to save as many men as possible. Some, though, were beyond help, and despite their best efforts, four of VMF-211's men—including Second Lieutenant Conderman—died that night. At Peacock Point, that afternoon, just down the coast from the airfield, "Barney" Barninger's men had completed their foxholes—overhead cover, sandbags, and chunks of coral would come later. Later, at dusk, Barninger evidently sensed that the atoll might be in for a long siege. Thinking that they might not be in camp again for some time, he sent some of his men back to Camp 1 to obtain extra toilet gear and clothing. In the gathering darkness, he set his security watches and rotated beach patrols and observers. Those men not on watch slept fitfully in their foxholes. That night, Wake's offshore guardians, Tambor to the north and Triton to the south, surfaced to recharge batteries, breathe fresh air, and listen to radio reports. From those reports the crews of the Tambor and Triton finally learned of the outbreak of war. The 9th of December dawned with a clear sky overhead. Over at the airfield, three planes took off on the early morning patrol, while Kinney had a fourth (though without its reserve gas tank) ready by 0900. A test flight proved the fourth F4F to be "o.k.," since she withstood a 350 mph dive "without a quiver." It was just in the nick of time, for at 1145 on the 9th, the Chitose Air Group struck again, as 27 Nells came in at 13,000 feet. Second Lieutenant David D. Kliewer and Technical Sergeant Hamilton attacked straggling bombers, and claimed one shot down. Battery D's number 2 and 4 guns, meanwhile, collectively fired 100 3-inch rounds. The Marines damaged 12 planes, but the enemy suffered only very light casualties: one man dead and another slightly wounded.

Once more, though, the Japanese wreaked considerable havoc on the defenders. Most of their bombs fell near the edge of the lagoon, north of the airfield, and on Camp 2, demolishing the hospital and heavily damaging a warehouse and a metal shop. One wounded VMF-211 enlisted man perished in the bombing of the hospital while the three-man crew of one of the dispersed gasoline trucks died instantly when a bomb exploded in the foxhole in which they had sought shelter. Doctors Kahn and Shank and their assistants evacuated the wounded and saved as much equipment as the could. Shank carried injured men from the burning hospital, courageous actions that so impressed Marine Gunner Hamas (who had been trapped by the raid while carrying a load of projectiles and powder to gun positions on Peale) that he later recommended that Shank be awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroism. The hard-pressed medical people soon moved the wounded and what medical equipment they could into magazines 10 and 13, near the unfinished airstrip, and established two 21-bed wards. Once the bombers had gone, the work of repairs and improving planes and positions resumed. That night, because the initial bombing had destroyed the mechanical loading machines, a crew of civilians helped load .50-caliber ammunition. That same evening, work crews dispersed food, medical supplies, water and lumber to various point around the atoll, while the communications center and Wake's command post were moved. Earlier that day from near the tip of Peacock Point, Marine Gunner Clarence B. McKinstry of Battery E had noted one bomber breaking off from the rest. Supposing that the plane had taken aerial photographs, he suggested that the battery be moved. That afternoon, First Lieutenant Lewis received orders to reposition his guns after dark; he was to leave two 3-inchers in place until the other two were emplaced, and then move the last two. Aided by about a hundred civilians with several trucks, Lewis and McKinstry succeeded in shifting the battery—guns, ammunition, and sandbags—to a new location some 1,500 yards to he northwest. Marines and workmen set up dummy guns in the old position. As the 10th dawned, Marine Gunner McKinstry found himself with new duties, having received orders to proceed to Wilkes and report to Captain Wesley McC. Platt, commander of the Wilkes strongpoint. Battery F comprised four 3-inch guns, but lacked crewmen, a heightfinder, or a director. Consequently, McKinstry could only fire the guns accurately at short or point-blank range, thus limiting them to beach protection. Assisted by one Marine and a crew of civilians, Gunner McKinstry moved his guns into battery just in time for the arrival of 26 Nells which flew over at 1020 and dropped their bombs on the airfield and those seacoast installations at the tip of Wilkes. While casualties were light—Battery L had one Marine killed and one wounded (one civilian suffered shell-shock)—the equipment and guns in the positions themselves received considerable damage. Further, 120 tons of dynamite which had been stored by the contractors near the site of the new channel exploded and stripped the 3-inch battery of its fresh camouflage. The gunners moved them closer to the shoreline and camouflaged them with burnt brush because they lacked sandbags with which to construct defensive shelters for the gun crews. In a new position, which was up the coast from the old one, Battery E's 3-inchers managed to hurl 100 rounds skyward while bombs began hitting near Peacock Point. The old position there was "very heavily bombed," and a direct hit set off a small ammunition dump, vindicating McKinstry's hunch about the photo-reconnaissance plane. Battery D's gunners, meanwhile, claimed hits on two bombers (one of which was seen to explode later). Although Captain Elrod, who single-handedly attacked the formation, claimed two of the raiders, only one Nell failed to return to its base. That night, the itinerant Battery E shifted to a position on the toe of the horseshoe on the lagoon side of Wake. Their daily defensive preparations complete, Wake's defenders awaited what the next dawn would bring. They had endured three days of bombings. Some of Cunningham's men may have wondered when it would be their turn to wreak destruction upon the enemy.

|