| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

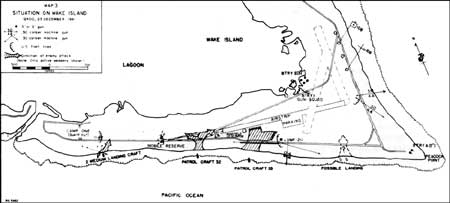

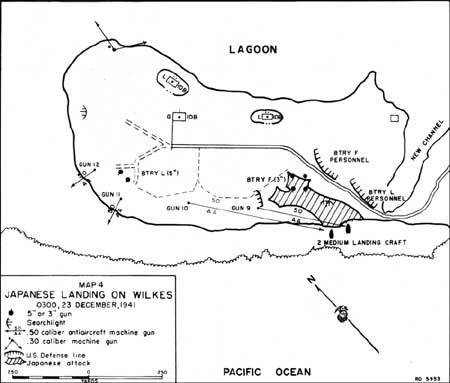

A MAGNIFICENT FIGHT: Marines in the Battle for Wake Island by Robert J. Cressman 'This Is As Far As We Go' Shortly after midnight, First Lieutenant Barninger noted flashing lights "way off the windy side of the island." Alerted to the odd display on the horizon in the darkness, Barninger telephoned Major Devereux, who replied that he also had seen it. Devereux directed Barninger to keep a watch out and cautioned the Peacock Point strongpoint commander to be mindful that the lee shore posed the most possibilities for danger. lookouts continued to note irregular flashes of light in the black, gust, rainy predawn of 23 December 1941. It may have been the Tenryu, the Tatsuta, and the Yubari firing blindly at what their spotters thought was Wake Island but which was, instead, only empty ocean. At 0415, however, a report came into the detachment commander's command post, telling of an enemy landing in progress at Toki Point, at the tip of Peale. Devereux alerted the battalion. Kessler, in the meantime, dispatched a patrol up the lagoon beach toward the PanAm facility, which met a patrol from Battery D. Neither had anything to report. On Wilkes, Captain Platt directed Battery L to move the men of two 5-inch gun sections (equivalent to two rifle squads) to the shore of the lagoon, west of the area of the new channel being dredged across the island. The rest of the men of the battery—fire controlmen and headquarters men under McAlister, who had established his command post near the searchlight section of the battery—moved into positions they had readied along the south shore of Wilkes, between McKinstry's Battery F and the new channel.

Kessler, whom Devereux had requested to confirm or deny the accuracy of the information regarding the landing, reported that there was no landing in progress, but that he had seen the lights offshore. Cunningham, at 0145, radioed the Commandant, 14th Naval District, reporting "gunfire between ships to northeast of island." Wake thus alerted, Second Lieutenant Arthur A. Poindexter, at Camp 1 with the mobile reserve (predominantly supply and administration Marines and 15 sailors under Boatswain's Mate First Class James E. Barnes), believed Peale to be threatened. He exercised initiative and entrucked eight Marines with four .30-caliber machine guns. Reporting his intention to the detachment commander, Poindexter and that portion of his mobile reserve sped past the airfield toward Peale. It was nearing Devereux's command post when he ordered it intercepted. The major retained Poindexter's little force where it was, pending clarification of the situation. The bad weather that prevented the Marines from seeing their foes likewise hindered the Japanese. Shortly before 0200, Special Naval Landing Force troops clambered down into the medium landing craft designated to land on Wilkes and Wake. Four landing craft were launched some 3,000 to 4,000 meters offshore, but in the squalls and long swells they experienced difficulty keeping up with Patrol Boat No. 32 and Patrol Boat No. 33 as they churned on a northeasterly course, headed for the beach. The landing craft designated to follow No. 32 lost sight of her in the murky, gusty darkness. At about 0230, Marines on Peacock Point detected the two patrol boats, which appeared to them only as dark shapes as they made for the reef by the airstrip. Then, the two ships ground gently ashore on the coral. The Japanese naval infantrymen slipped over the side into the surf, struggled ashore, and sprinted across the coral for cover. On Wilkes, Gunner McKinstry called to Captain Platt and informed him that he thought he heard the sound of engines over the boom of the surf, and at 0235 one of his .50-caliber guns (gun no. 10) opened fire in the darkness. Ten minutes later, McKinstry, having sought permission to use illumination, caused a searchlight to be turned on. Although the light was shut off as suddenly as it had been turned on, its momentary beam revealed a landing boat aground on Wilkes' rocky shore and, beyond that, two destroyers, beached on Wake.

McAlister ordered Platoon Sergeant Henry A. Bedell to detail two men to hurl grenades into the enemy craft. The veteran non-commissioned officer, accompanied only by Private First Class William F. Buehler, gamely tackled the task, but Japanese gunfire killed Bedell and wounded Buehler before either had been able to work their way close enough to lob grenades into the boats. McKinstry's men, meanwhile, manned the 3-inchers of Battery F, but the guns could not be depressed enough to fire onto the beach. The Marines held their position until the men from the Takano Unit of the Special Naval Landing Force approached closely enough to begin lobbing grenades. Marines and Japanese grappled in the darkness, hand-to-hand, before McKinstry's men, after removing the firing locks from the guns, pulled back to take up infantry positions. Their concentrated fires kept most of the Japanese at bay near the 3-inch gun position. Other Special Naval Landing Force troops, however, probed westward, toward the 5-inch guns that had so humbled Kajioka's force on the 11th. They ran into heavy fire from gun no. 9, a well-camouflaged .50-caliber Browning, handled skillfully by 20-year old Private First Class Sanford K. Ray and situated some 75 yards west of where the Takano Unit had first swarmed ashore. Ray's fire prevented the enemy from advancing closer than 40 or 50 yards from his sand-bagged position, and his proximity to the beach allowed him not only to harass the enemy but also to report enemy movements. Although Japanese troops had severed most wire communication lines, Platt remained in touch with developments at the shoreline by reports from Ray. Reports from observers along the beach soon began to deluge Devereux's command post, where he and his executive officer, Major Potter, attempted to keep abreast of events. Gunner Hamas relayed the information to Cunningham, at his command post. On the basis of those reports, the island commander, at 0250, radioed the Commandant of the 14th Naval District: "Island under gunfire. Enemy apparently landing." At that point, Devereux directed Poindexter to move the mobile reserve into me area between Camp 1 and the west end of the airfield. Since the eight Marines had remained in the truck with the four machine guns, only 15 minutes elapsed before they set up both gun sections in a position commanding the road that ran along the south shore and also covering a critical section of beach. Within moments, Poindexter's Brownings chattered and spat into the dim shape of the grounded Patrol Boat No. 32, most of the bullets striking the after part of the ship. Special Naval Landing Force troops who disclosed their position by igniting flares soon came under fire. At Camp 1, just up the coast, men from Battery I and the sailors who had been serving as lookouts manned the four .30-caliber machine guns set up there. From Poindexter's vantage point, the enemy troops appeared confused and disoriented, shouting and discharging a number of flares, perhaps for "control and coordination." Having received a report of Japanese destroyers standing toward Wake's south shore (and well inside the range of the 5-inch batteries that had so vexed the enemy on 11 December), Second Lieutenant Robert M. Hanna, who commanded the machine guns emplaced at the airstrip, clearly perceived the threat. Accompanied by Corporal Ralph J. Holewinski and three civilians, Paul Gay, Eric Lehtola, and Bob Bryan, Hanna set off at a dead run for the 3-inch gun that had been emplaced on the landward side of the beach road, on a slight rise between the beach road and the oiled tie-down area at the airstrip. Up to that point, Major Putnam's grounded airmen, their ground support unit, and the volunteer civilians, had been awaiting further orders. As Hanna and his scratch 3-inch crew sprinted to the then-unmanned gun, Devereux ordered Putnam to support the lieutenant.

Putnam assigned Second Lieutenant Kliewer to a post on the west end of the airfield, along with Staff Sergeant John F. Blandy, Sergeant Robert EW. Bourquin, Jr., and Corporal Carroll E. Trego. They were to set off the mines on the field if the enemy attempted to use it. Two .50-caliber guns situated just north of the airstrip covered Kliewer's position. At the eastern end of the strip lay the guns manned by Corporal Winford J. McAnally, along with six Marines and three civilians and supported by a small group of riflemen. The gunners enjoyed a perfect, unobstructed field of fire—the airstrip itself. About 0300, just at a time when events began to develop with startling rapidity as the Japanese pushed ashore on Wilkes and Wake, Major Devereux lost touch with Camp 1, Putnam's platoon, Hanna's command post near the airstrip, and Barninger's Battery A. Advancing Japanese troops probably had found the communication lines—the exigencies of war had prevented them from being buried—and cut them. Devereux's last situation reports from those units painted a bleak picture. If Cunningham received less-than-encouraging reports from the defense battalion commander, he received equally grim news from CinCPac when, at 0319 Wake time, Pearl Harbor radioed to Wake that the Triton and Tambor were returning to Hawaiian waters. "No friendly vessels should be in your vicinity today," the message stated, "Keep me informed." Hanna and his men, meanwhile, reached the 3-inch gun and set to work. Anxious hands fumbled in the darkness for ammunition while Hanna—since the gun lacked sights—peered down the bore to draw a bead on the beached and stationary Patrol Boat No. 33 that lay less than 500 yards away. The first round tore into the ship's bridge, seriously wounding both the captain and navigator, killing two seamen, and wounding five. Hanna's gun hurled 14 more rounds on target. Some of his projectiles evidently touched off a magazine, and the beached warship began to burn. The illumination provided by the burning ship revealed her sistership, which Hanna and his hard-working gunners bombarded, as well. A short time later three Special naval Landing Force sailors attacked Hanna's exposed position. In the ensuing fight, Hanna coolly shot and killed all three enemy sailors with his pistol and resumed the operation of his 3-incher.

Reinforcing Hanna's connoneers became the next order of business. Devereux felt compelled to keep Peale's Battery B intact to deal with surface threats, and Battery E (which, by that point, had a full complement of guns and crews along with the only heightfinder and director) to deal with enemy planes. That left Godbold's Batter D, which by that point possessed only two operational guns and no fire-control gear. Devereux directed Godbold to send one section (nine men) to the battalion command post to reinforce Hanna's crew. Under Corporal Leon A. Graves, the squad clambered on board a contractor's truck and reached the command post about 0315. They were to proceed along the road that paralleled the shoreline to a junction some 600 yards south of the airfield, where they were to leave the truck and proceed through the brush to Hanna's position. Quickly, they set out into the night. The flames from the wrecked Patrol Boat No. 33 disclosed Japanese troops advancing past the west end of the airstrip into the thick undergrowth in front of the mobile reserve's positions. Poindexter, after ordering one machine gun section to keep up a fire into the brush to interdict that movement and protect his own flank, heard machine gun fire from Camp 1, behind him. Wanting to see for himself if more Japanese landing craft were coming ashore to his rear, the lieutenant, accompanied by his runner, left the front in charge of Sergeant "QT" Wade, and hurried back to the camp.

There, unable to see at what his neophyte sailor-gunners were expending their ammunition, Poindexter asked each to point out his target. Two could not—they'd opened fire only because the other two had done so—but a third pointed to the dim outline of what appeared to be a "large landing barge on the order of a self-propelled artillery lighter." When another craft of the same type seemed to materialize out of the murk, Poindexter ordered firing resumed at what proved to be two large landing craft that were attempting to ground themselves 1,200 yards east of the entrance to Wilkes Channel. The enemy coxswains, however, appeared to be having difficulty coaxing the unwieldy landing craft onto the beach, backing off and trying again and again to land the Special Naval Landing Force men crouched behind the gunwales, which seemed to be deflecting the .30-caliber bullets peppering them. Seizing the moment, Poindexter called for volunteers to pick their way down the rocky beach to the water's edge, there to lob grenades into the boats. Poindexter organized two teams—Mess Sergeant Gerald Carr and a civilian, Raymond R. "Cap" Rutledge (who had served in the Army in France in World War I), in one, Poindexter and Boatswains' mate First Class Barnes in the other. The grenadiers dashed to the water's edge while the machine guns momentarily held their fire. Barnes, taking cover behind coral heads, remained hidden until the barges ground ashore again. Then, exposing himself to enemy fire, he hurled several grenades toward the Japanese craft, and managed to land at least one inside, killing or wounding many of the troops on board. The valiant efforts of Poindexter and his men, however, stopped the Japanese just momentarily, for soon they began swarming ashore and moving inland. Shortly before the wire communications to Devereux's command post failed, Poindexter reported the result of his foray. Having seen flares streaking skyward in the murk, Captain Godbold on Peale, meanwhile, sent out two patrols, one to move westward toward the naval air base, and the other to go eastward along the lagoon's shore. Neither patrol encountered any enemy troops. A half-hour later, Godbold established an outpost at the bridge connecting Peale and Wake.

Meanwhile, after word of the enemy landing reached Pearl Harbor, Vice Admiral Pye convened a meeting of his staff. By 0700 (22 December, Hawaiian time), having received further word of developments at Wake, Pye estimated that a relief of the island looked impossible, given the prevailing situation, and directed that the Tangier should be diverted toward the east. With the relief mission abandoned, should his forces attack the enemy forces in the vicinity of Wake? Or should American forces be withdrawn to the east? He feared that the timing of the Japanese carrier strikes and the landing then in progress indicated that the enemy had "estimated closely the time at which our relief expedition might arrive and may, if the general location of our carrier groups is estimated, be waiting in force." American forces could inflict extensive damage upon Japanese, Pye believed, if the enemy did not know of the presence of the U.S. carrier forces. They had not yet seen action, though, and no one could overestimate the danger of having ships damaged 2,000 miles from the nearest repair facilities—"a damaged ship is a lost ship," Brown had commented in Task Force 11's war diary. Damage to the carriers could leave the Hawaiian Islands open to a major enemy thrust. "We cannot," Pye declared, "afford such losses at present." Two course of actions existed—to direct Task Force 14 to attack Japanese forces in the vicinity of Wake, with Task Forces 8 and 11 covering Task Force 14's retirement, or to retire all forces without any attempt to attack the enemy. These choices weighed heavily on Pye's mind. If American forces hit the Japanese ships at Wake and suffered the loss of a carrier air group in the process, Pye deemed the "offensive spirit" shown by the Navy as perhaps worth the sacrifice. However, in the midst of his deliberations, shortly after 0736, Pye received a message from the CNO which noted that recent developments had emphasized that Wake was a "liability" and authorized Pye to "evacuate Wake with appropriate demolition." With Japanese forces on the island, though, Pye felt that capitulation was only a matter of time. "The real question at issue," Pye thought, "is, shall we take the chance of the loss of a carrier group to attempt to attack the enemy forces in the vicinity of Wake?" Radio intelligence from the previous day linked "CruDiv 8 ... CarDiv 2" and erroneously, "BatDiv 3" (consisting of two battleships) with the forces off of Wake. A pair of Kongo-class fast battleships, supported by carriers and heavy cruisers would easily have overmatched Fletcher's Task Force 14. In the meantime, Japanese cruisers—probably the Yubari, Tenryu, and Tatsuta—had begun shelling Wake, further discomfiting the defenders. Despite Lewis' Battery E firing "pre-arranged 3-inch air burst concentrations" over the Japanese beachhead, the enemy continued to press steadily toward VMF-211's position around Hanna's 3-inch gun. Major Putnam, already wounded in the jaw, with blood from his wound staining the backs of the snapshots of his little daughters, which he carried in his pocket, formed his final line. "This," he said, "is as far as we go." Putnam had placed Captain Elrod in command of one flank of VMF-211's defensive line, which was situated in dense undergrowth. In the impenetrable darkness, the squadron executive officer and his men—most of whom were unarmed civilians who acted as weapons and ammunition carriers (until weapons became available)—conducted a spirited defense which repeated attacks by Special Naval Landing Force troops could not dislodge. Each time he heard Japanese troops mounting a probe of 211's position, Elrod interposed himself between the enemy and his own men and provided covering fire to enable his detachment to keep supplied with guns and ammunition. Shortly before dawn, a Japanese sailor who had hidden himself among the heaps of casualties surrounding Hanna's gun shot and killed the gallant Captain Elrod. Captain Tharin, in charge of a group of Marines on the left flank of VMF-211's line, delivered covering fire for the unarmed ammunition carriers attached to his unit, which repulsed several assaults on his position. At one point, Japanese sailors penetrated the defenses in Tharin's sector, but in the counterattack, which drove the enemy from the position, Tharin captured an enemy automatic weapon and used it "successfully and effectively against its former owners." The indomitable Aviation Machinist's Mate First Class Hesson armed himself with a Thompson sub-machine gun and some grenades and although wounded by rifle fire and grenade fragments, single-handedly drove back two concerted attacks—killing several Japanese and preventing them from overrunning 211's flank. Despite the heroic efforts of Putnam's "platoon," the Japanese managed to move into the roughly triangular area which was bounded by Peacock Point, on one side, the beach and the south side of the airstrip on the others. Corporal Graves' squad from Battery D, meanwhile, detrucked somewhat north of their intended destination (200 yards south of the airstrip rather than 600), began walking toward VMF-211's position, and quickly encountered a Japanese patrol. In the ensuing fire-fight, enemy machine gun and rifle fire killed one Marine and pinned down the remainder for a time, until Graves and his men managed to extricate themselves and retire northward toward the battalion command post. Graves' encounter indicated that the Japanese had penetrated the U.S. defenses. Despite their extraordinary efforts, neither Kliewer and the .50-caliber guns at the airfield, nor the Hanna-VMF-211 group at the 3-inch gun near the shore, had been able to stop them. At the same time, Batteries A and E began to receive mortar, small arms, and machine gun fire, prompting Barninger to deploy his range section, armed with two .30-caliber Brownings, and deployed as infantrymen, facing northwest "across the high ground to the rear of the 5-inchers at Peacock Point. Lewis, whose 3-inch fire had silenced an automatic weapons position in the thick undergrowth southwest of Battery E, dispatched a patrol to try to relieve the pressure on his position. That group, under Sergeant Raymond Gragg, progressed on 50 yards beyond the perimeter before it came under heavy fire. That Japanese, however, moved no further because of the resistance put up by Gragg's squad.

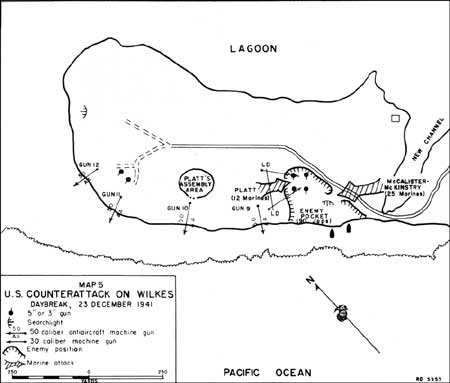

Amidst the chaos, Devereux groped for information about the progress of the battle. At some point, he received word from one of the few positions which had retained wire contact with his command post, Corporal McAnally's machine gun section, which was located at the eastern end of the airstrip. McAnally reported that the Japanese were advancing up the shore road, apparently intent upon launching a thrust up the other prong of Wake. With one unit besetting Putnam's at the airstrip, another Japanese unit skirted Putnam and Hanna and was headed into the triangular end of Peacock Point. McAnally, establishing contact with the .50-caliber machine guns on the east shore of Wake, some 400 yards south, carried on a "resolute, well-coordinated defense" which stymied the enemy in the area. Perhaps more important, McAnally served as Devereux's eyes and ears on that portion of the battlefield. On Wilkes, Private First Class Ray's defense of his position equaled that of McAnally's. Captain Platt, having lost communication with his own posts and also with the defense battalion command post, set out on a personal reconnaissance mission at about 0430. He crawled through the thick underbrush and picked his way across the rocky beach, until, at about 0400, he came to a place east of gun no. 10 where he could see Special Naval Landing Force men massed in and about Battery F's guns. Soon thereafter, while clambering back to he gun, Platt met Sergeant Raymond L. Coulson and ordered him to gather two .30-caliber machine gun crews and their guns at Kuku Point (where they had been sent during the false alarm earlier that morning), along with the searchlight crew and everyone else he could find, and to return to gun no. 10. Devereux, still isolated from his units and literally in the dark about the actions on Wilkes and those in the vicinity of Camp 1, attempted as best he could to keep the island commander informed. Cunningham, consequently, also had scant comprehension of the way the fighting was progressing in those areas. At 0500, about the time Captain Platt was reconnoitering the Japanese position on Wilkes, Cunningham radioed Commandant 14th Naval District, "Enemy on island. Issue in doubt." Poindexter, meanwhile, satisfied that Camp 1 was being defended as well as possible, proceeded to the mobile reserve gun positions on the west side of the airfield. Japanese machine gun and mortar fire, accompanied by "much shouting" and "numerous pyrotechnic flares," began to fall around those positions, partially disabling one U.S. gun section. As the sky over Wake began to lighten with the dawn, Poindexter became concerned about the enemy fire that had begun to land near his men, and also that the enemy troops infiltrating the woods might outflank the mobile reserve. He ordered a retirement toward Camp 1. The sections alternated in covering each other throughout the movement, maintaining a steady volume of fire. Reaching Camp 1 after daylight, Poindexter established a north-south line astride the shore road, east of a prominent water tank. While Poindexter deliberated the situation facing his force, Japanese movement along the east shore road increasingly pressed Corporal McAnally's group. McAnally communicated his difficult situation to Devereux's command post. Japanese hand grenades and small arms fire made life difficult for McAnally's band, which nevertheless held its ground and broke up several assaults. Around 0530, Devereux told Major Potter to form a final defensive line astride the north-south road, which was being threatened from the south by the advancing Japanese. Calling Godbold's Battery D into the action soon thereafter, Devereux committed his last reserve troops into the action on the east side of Wake. Aware of Corporal McAnally's predicament, Devereux ordered the corporal's combat group to withdraw northward, toward the command post, to join Major Potter's detachment. On Wilkes at about that time, Sergeant Coulson rejoined Captain Platt with the two machine-gun crews and guns, and eight riflemen. The surf that had masked the sound made by the invaders now worked to the advantage of the hard-pressed defenders. Along with the sputter and crackle of gunfire along the south shore of Wake and on Wilkes, it prevented the Japanese from discovering Platt's briefing of his Marines for the assault on the abandoned Battery F position. In the waning darkness, Platt and his men crept toward the enemy, reaching a point less than 50 yards away from the abandoned 3-inchers. On Platt's signal the two machine guns chattered and spat toward the enemy position. His skirmishers charged forward and soon began engaging the Japanese—who, with no security on the west, were taken completely by surprise, and whose only light machine guns had been emplaced facing eastward, toward the old channel. Almost simultaneously with Platt's assault, but not at all coordinated with it, McAlister (who lost contact with the Wilkes strongpoint commander soon after the enemy landing) and his men encountered and engaged a small enemy patrol on the beach ahead of them, killing one man before the rest took cover behind some coral boulders. While flanking fire pinned down the enemy, Gunner McKinstry started forward to clean out that pocket of resistance. McAlister stopped him but as he was telling the Gunner to detail one of the men to do it instead, Corporal William C. Halstead climbed atop the rocks and slew the remainder of the enemy. Platt's and McAlister's assaults cleaned out the Japanese in the 3-inch gun position. Platt and McAlister reorganized their units and searched for any enemy troops who might have escaped. They encountered no further resistance and took two prisoners, who had been wounded and had feigned death. The Marines counted at least 94 dead Japanese. American losses included nine Marines and two civilians killed; four Marines and one civilian wounded. Meanwhile (shortly before dawn) on Wake, Japanese troops surrounded Kliewer's position. The four Marines, however, armed with only two Thompsons, three .45-caliber pistols, and two boxes of hand grenades, repelled multiple bayonet charges in the darkness. Dawn revealed a full-scale enemy attempt to carry the post, but Kliewer and his three shipmates, backed up by the two .50-caliber machine guns 150 yards behind them, killed many of the attacking Japanese and continued to hold their ground. On Peale, with the departure of Captain Godbold and the Marines of Battery D for the island's command post on Wake, First Lieutenant Kessler became strongpoint commander. At dawn, he scanned the other islets. On Wilkes, he discerned Japanese flags whipping in the breeze—one particularly large one flying where Battery F had been (flags which Platt's men would remove shortly thereafter). Kessler reported his observations to Devereux, who had not heard a word from Platt since around 0300. The report prompted Devereux to fear that Wilkes had fallen. As he scanned Wake at about 0600, however, Kessler observed the masts of what proved to be Patrol Boat No. 32, which was aground on the south shore of Wake. Kessler requested permission to fire at the ship. His request was approved, but he was admonished to avoid firing into friendly troops. Kessler ordered his 5-inchers to open fire. The first salvo clipped off the mainmast. Then Battery B's gunners lowered their sights to hit the ship itself. They could see only the funnel tops over the intervening island. Twenty-five minutes later, at 0625, the command post ordered Battery B to cease fire, their target having been "demolished." Twenty minutes later, Kessler observed four "battleships, or super heavy cruisers" (probably the heavy cruisers Aoba, Kinugasa, Furutaka, and Kako) off Heel Point, moving westward but remaining well out of range. Those ships lay 10 kilometers off shore and shelled the atoll, but achieved little success. Additional Japanese forces were headed for Wake. At 0612, off to the northwest, Soryu turned into the wind and launched 12 planes. The day's air operations had begun. In less than an hour, the planes were over the island. Throughout the battle, Major Devereux had, as well as he could, kept the island commander informed of the progress of the assault. While the Marines, assisted by the sailors and civilians, had been attempting to stem the tide, most of the news which trickled into Cunningham's command post boded ill. At 0652, he sent out a message reflecting the situation as he knew it: "Enemy on island. Several ships plus transport moving in . Two DD aground." That was at 1032, 22 December 1941, on Pearl Harbor. It was to be the last message from the Wake Island defenders. At Pearl Harbor, at about the time that Cunningham was sending that last message, Vice Admiral Pye had reached making a decision. He concluded that if Task Force 14 encountered anything but a weaker Japanese force, the battle would be fought on Japanese terms while within range of shore-based planes and with American forces having only enough fuel for two days of high speed steaming. Like Brown, Pye believed that a damaged ship was a lost ship, especially 2,000 miles from Pearl Harbor. The risk, he believed, was too great. He ordered the recall of Task Forces 14 and 11, and directed Task Force 8 to cover the retirement. Frank Jack Fletcher's Task Force 14, meanwhile, was right on schedule, and was in fact further west that Pye knew. His ships fully fueled and ready for battle, Fletcher planned to detach the Tangier and two destroyers for the final run-in to Wake, while the pilots on board the Saratoga prepared themselves for the fight ahead. Fletcher, not one to shirk a fight, received the news of the recall angrily, He ripped his hat from his head and disgustedly hurled it to the deck. Rear Admiral Aubrey W. Fitch, Fletcher's air commander, similarly felt the fist-tightening frustration of the recall. He retired from the Saratoga's flag bridge as the talk there reached "mutinous" proportions. As word of the recall circulated throughout Task Force 14, reactions were pretty much the same. Pye's recall order left no latitude for discussion or disobedience; those who argued later that Fletcher should have used the Nelsonian "blind eye" obviously failed to recognize that, in the sea off Copenhagen, the British admiral could see his opponents. Fletcher and Fitch, then 430 miles east of Wake, could not see theirs. They had no idea what enemy forces they might encounter. The Japanese had beaten them to Wake.

|