| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

UP THE SLOT: Marines in the Central Solomons by Major Charles D. Melson, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) Milk Runs and Black Sheep The first Marines to fight at New Georgia were the aircrews who were sent to blunt Japanese efforts to establish an airfield at Munda Point in December 1942. Thus began a routine air and sea pounding of the Munda Airfield until ground forces could capture it for Allied use. For Marine flyers, these missions evoked "a parade of impressions — long over-water flights; jungle hills slipping by below; the sight of the target — airfield, ship, or town, some times all three; the attack and the violent defense; and then the seemingly longer, weary return . . . ." The role of land-based aviation in the Central Solomons Campaign was critical, because the Japanese air effort had to be neutralized before Allied air and ground forces could climb up the Solomons ladder towards Rabaul. Unless the Allies could capture suitable airfields closer to the Japanese base areas at Rabaul and Bougainville, the air war would be limited in range and effect. The Guadalcanal airfields were 650 miles from Rabaul, Munda Point was a somewhat-closer 440 miles. For Marines aviators, Munda was a rung on the ladder that ended at Rabaul. The air war for the Central Solomons was a series of sorties — fighter sweeps and bombing runs. For aviation units, the operating area was divided into the combat area, the forward area, and the rear area. These zones shifted as the campaigns moved north towards the Rabaul area. While the 1st and 2d Marine Aircraft Wings were present in the Southern Pacific, Marines flew under a joint air command, Commander Aircraft Solomons (ComAirSols). Rear Admiral Marc A. Mitscher's ComAir Sols was comprised of three subordinate segments: Bomber, Fighter, and Strike Commands. Strike Command was led by Colonel Christian F. Schilt, who had been awarded a Medal of Honor for heroism in Nicaragua in 1928, and Fighter Command was under Colonel Edward L. Pugh; both veteran Marine aviators in a structure where experience, "not rank, seniority, or service," was paramount. The Marine squadrons flew Grumman F4F Wildcats, Grumman F6F Hellcats, and Chance-Vought F4U Corsairs in Fighter Command; and Grumman or General Motors TBF Avenger torpedo bombers and Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers in Strike Command. Also operating in the theater was Marine Aircraft Group 25, the South Pacific Combat Air Transport Command (SCAT), which flew unarmed transport planes, Douglas R4D Skytrains, bringing in supplies and replacements and evacuating wounded without fighter escorts such as the bombing missions had. Some 40 other squadrons were in rearward bases, making a total of 669 aircraft available for the Central Solomons campaign. They were opposed in the air by the Japanese Eleventh Air Fleet and Japanese Army air units defending New Guinea.

The Corsair, known as the "Whistling Death" to the Japanese and the "Bent Wing Widow Maker" to the Marines, was delivered in March 1943 in time to have eight Marine squadrons available for the New Georgia campaign. The Corsair, along with the new F6F Hellcat fighter, dominated the air-to-air battle to sweep the skies of the Japanese. This superiority was enhanced by Army Air Corps aircraft, the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, for example. Once introduced, each new aircraft version could do a little more than the basic models; it could fly higher, fly longer, and carry more armament than its predecessor. Advances in radio detection and ranging (radar) and communications continued as well to ensure the control systems kept pace with the aircraft. One Marine with Fighter Command, Major John P. Condon, recalled that ComAirSols routinely struck the airfields of southern Bougainville "with escorted bombers, night attacks by Navy and Marine Corps TBFs, and some mining at night of the harbors." He went on to observe that the shorter-range SBDs were "invariably escorted in their routine reduction efforts against the fields in New Georgia." Routine did not mean safe, as the Japanese just as routinely made their fighter presence known. Naval officer and novelist James A. Michener heard a pilot observe that he was "damned glad to be the guy that draws the milk runs." But, "if you get bumped off on one of them, why you're just as dead as if you were over Tokyo in a kite." One incident occurred that symbolized the joint nature of the air effort, the destruction of the aircraft transporting Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, who had planned the attack on Pearl Harbor. Allied intelligence agencies learned that the admiral and his staff would fly to Kahili on 18 April 1943. Admiral Mitscher ordered Fighter Command to intercept Yamamoto's aircraft. Planning for this mission fell to the Fighter Command's deputy, Lieutenant Colonel Luther S. Moore, who scheduled Army long-range P-38 Lightnings fitted with Navy navigational equipment for the task. The flight plan was prepared by the command operations officer, Major Condon. Yamamoto's plane was intercepted and shot down, ending the life of one of Japan's major combat leaders. At the end of April 1943, the Japanese Eleventh Air Fleet launched a series of determined, but unsuccessful, attacks to disrupt the Allied buildup on Guadalcanal and in the Russell Islands. These continued through the month, and on 16 June, ComAirSols planes intercepted and virtually destroyed 100 Japanese aircraft before they reached their target, the New Georgia invasion fleet. By the end of the month, the Allied forces were landing on New Georgia and the Japanese lost the battle to disrupt the offensive. The Japanese responded with repeated raids against shipping and landing areas, but the balance of air power was decidedly with Commander Aircraft Solomons. A Marine air man wrote that the Japanese were creating an ever-growing number of Marine, Army, and Navy fighter aces in the process. By June, Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 21 was pounding away at Munda, but not without losses. Flying from Guadalcanal and Russell Islands, ComAirSols fighter and strike aircraft covered the Toenails landings and subsequent operations ashore. From 30 June 1943 through July, there were only two days that did not have "Condition Red" and dogfights with Japanese aircraft over the objective area by Allied combat air patrols. At the same time, Japanese naval forces were located and attacked, thus forcing the Japanese to move at night by circuitous routes with landing barges alone. Bomber and Strike Command aircraft ranged as far north as Ballale, Buin, Kahili, and the Shortlands in concert with Fifth Air Force strikes at the same locations.

Despite this pressure, the Japanese continued to attack Allied forces from the air, ComAirSols planes were not able to operate effectively at night within range of Allied antiaircraft artillery that could not tell friendly from enemy aircraft. An other obstacle to total Allied success was the dense jungle-covered terrain that hindered identification targets and accurate assessment of the results of air strikes. For efficient air control for the New Georgia operation, Admiral Mitscher set up a new command, Commander Aircraft New Georgia (ComAir New Georgia), as part of the landing force and under Marine Brigadier General Francis P. Mulcahy, who commanded the 2d Marine Aircraft Wing. ComAir New Georgia had no aircraft of his own, but controlled everything in the air above or launched from a New Georgia airfield. Mulcahy and his staff ensured command, control, and coordination of direct support air for the New Georgia Occupation Force after it had landed. ComAir New Georgia established its command on Rendova after the assault waves landed on D-Day, 30 June 1943. From Rendova, he began to integrate the air defense and support system to provide XIV Corps with direct air support. On 11 July, Commander Aircraft Segi under Lieutenant Colonel Perry O. Parmelee was established under Mulcahy's direct command. The ground forces were ashore on New Georgia and pushed ahead at Zanana and Laiana and were poised at the edge of Munda Airfield at the end of July. Mulcahy provided air support to the infantry advance at Munda Point and against other Japanese-held areas on New Georgia. By the end of the campaign, Mulcahy had ordered over 1,800 preplanned sorties mainly flown by SBDs and TBFs against targets at Viru, Wickham, Munda, Enogai, and Bairoko.

In addition, there were some 44 close air support strikes using ad hoc forward air control and tactical air control parties from Mulcahy's command. This was a significant step in the evolution of the air control system that eventually formed the air-ground team for the Marines. Close air support missions were planned in detail the day prior to execution. The requested missions went to Mulcahy and, if he approved, they then were forwarded to Guadalcanal, the Russells, or Segi Point for scheduling. The next day these aircraft reported to a rendezvous point and contacted an air support party on the ground which used radio, lights, smoke, or air panels to direct the strike. General Mulcahy commented that the use of aircraft close to the frontlines "proved to be impractical" with accuracy. The R4D Skytrains of MAG-25 de livered 100,000 pounds of food, water, ammunition, and medicine that was the Northern Landing Group's only source of supply at times. This support prompted one Marine raider to ask that the air drop containers be combat, or spread, loaded as on one occasion they re covered 19 of a 20-container load drop and "only later discovered the missing drop contained medicinal brandy." Air drops of supplies went to the other ground forces as well, throughout a campaign fought in difficult, trackless, terrain.

On 25 July, a massive strike consisting of 66 B-17 and B-24 bombers in concert with naval gunfire ships struck at Lambetti Plantation, followed by an 84-plane strike on antiaircraft artillery positions at Biblio Hill. This was coordinated with the final drive to take the campaign's main objective, Munda airstrip. The Japanese continued to delay the 43d Infantry Division and another strike followed on l August by a 36-plane attack of SBDs and TBFs, protected by some 30 fighters. After the capture of Munda Point, General Mulcahy moved his command from Rendova to Munda airfield to set up strike and fighter control at Kokengolo Hill, In a Japanese-built tunnel that Navy Seabees had cleared of debris and dead, Mulcahy was able to conduct round-the-clock operations. The first fighters assigned to Munda landed at 1500 on 14 August. While safe, the Seabee-cleared shelter was also hot and smelled of its former dead occupants. On 15 August, Mulcahy sent VMF-123 and -124 fighters from Munda and Segi fields to cover the Vella Lavella landings, during which they claimed 26 Japanese aircraft downed. On this day, VMF-124's First Lieutenant Kenneth A. Walsh began a streak that would eventually earn him the Medal of Honor for shooting down 21 Japanese aircraft. After accounting for three aircraft over Vella Lavella, he brought his Corsair back to Munda Field with 20mm holes in the wings, several hydraulic lines cut, a holed vertical stabilizer, and a flat tire.

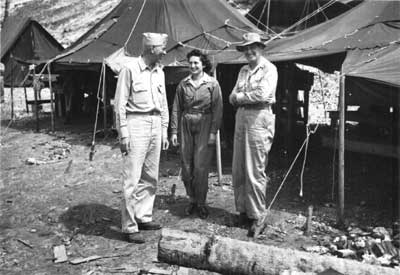

From 16 through 19 August 1943, the Japanese shelled the airfield in the day and bombed it at night. The artillery threat was eliminated with the capture of Baanga Island, but the air raids continued with intermittent bombing and strafing through the fall. From then, until the establishment of airfields on Bougainville three months later, Munda Field was the scene of intense activity as planes landed and took off to strike at Rabaul and Japanese shipping which were first trying to supply, and then evacuate, ground forces. Many barges were destroyed in the withdrawal that took some 9,400 Japanese off Kolombangara. Admiral Halsey believed that 3,000 to 4,000 other Japanese were killed during these evacuations. Captain John M. Foster, an F4U pilot, wrote about flying during this time and his first mission from Munda, "Never had I attempted to land a plane on a field as narrow and short as the Munda strip," he recalled. Rolling onto the taxiway, he was thankful for the 2,000 horsepower of engine to "plow through the mud." The crews lived in tents and messed in a screened framed building chow-hall which the Seabees built. The air units provided dawn to dusk coverage, with the night spent in rest and recovery. The night's sleep was often disrupted by the appearance of a single Japanese bomber variously called "Washing Machine Charlie," "Louie the Louse," "Maytag Charlie," or "other names less printable."

On 24 August, ComAir New Georgia at Munda was relieved by Commander Aircraft Solomon's Fighter Command, at which time, General Mulcahy turned over his responsibilities to Colonel William O. Brice. Mulcahy's staff continued to coordinate liaison and spotter aircraft and strike missions launching from Munda Field until relieved of these responsibilities by ComAirSols on 24 September. "Success in the air is a lot of little things," observed VMF-214's commander and Medal of Honor recipient, Major Gregory (Pappy) Boyington, and most of them "can be taken care of before takeoff." With the Japanese air bases now within closer range of Allied aircraft, Boyington and others conducted fighter sweeps of 36 to 48 planes that were classics of their kind. Throughout this, escorted bomber and strafing attacks continued. The capture and use of Munda Field was now felt by the Japanese "in spades" observed Fighter Command's Condon, as dive bombing and strafing attacks against the enemy were daily routine. On 28 August, First Lieutenant Alvin J. Jensen of VMF-214 was lost in a rainstorm over Kahili and when he broke through the clouds he found himself inverted over the Japanese field. Turning wings level, he proceeded to shoot up the flight-line and accounted for 24 enemy aircraft on the ground. Photographs confirmed the damage and Jensen earned the Navy Cross for this work, described as "one of the greatest single-handed feats" of the Pacific War. During this time, Lieutenant Colonel Frank H. Schwable's VMF(N)-531 arrived in the Russells to begin night-fighter operations along with a similar Navy unit. Using ground-controlled radar intercept vectors, the squadron's Lockheed PV-1 Venturas then closed for the kill using the aircraft's on-board radar. This began the Marines' ability to deny the Japanese the cover of darkness over Vella Lavella and elsewhere. Air support during the Central Solomons campaign was considered of high quality by all commanders. Aviation historian and veteran Pacific War correspondent Robert Sherrod estimated that of the 358 aircraft the Japanese lost during this campaign, 187 were destroyed by Marine air. More significant were the resultant deaths of highly trained and experienced pilots and crews whom the Japanese could not replace. Marine aviation unit casualties for operations in the Central Solomons were 34 of the 97 Allied aircraft lost. As a postscript to New Georgia operations, on 20 October 1943, Commander Aircraft Solomons moved to Munda to use the airfield as his headquarters from which he would fight the New Britain and Bougainville campaigns.

|