|

TIME OF THE ACES: Marine Pilots in the Solomons

by Commander Peter B. Mersky, U.S. Naval Reserve

The One and Only 'Pappy'

Every one of the Corps' aces had special qualities

that set him apart from his squadron mates. Flying and shooting skills,

tenacity, aggressiveness, and a generous share of luck — the aces

had these in abundance. One man probably had more than his share of

these qualities, and that was the legendary "Pappy" Boyington.

|

|

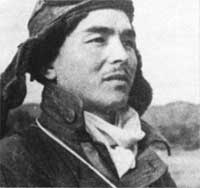

Major Gregory "Pappy" Boyington. Author's Collection

|

A native of Idaho, Gregory Boyington went through

flight training as a Marine Aviation Cadet, earning a reputation for

irreverence and high jinks that did not go down well with his superiors.

His thirst for adventure, as well as his accumulated financial debts,

led him to resign his commission as a first lieutenant and join the

American Volunteer Group (AVG), better known as the Flying Tigers. Like

other service pilots who joined the AVG, he first resigned his

commission and this letter was then put in a safe to be redeemed and

torn up when he rejoined the Marine Corps.

Boyington claimed to have shot down six Japanese

aircraft while with the Flying Tigers. However, AVG records were poorly

kept, and were lost in air raids. To compound the problem, the U.S. Air

Force does not officially recognize the kills made by the AVG, even

though the Tigers were eventually absorbed into the Fourteenth Air

Force, led by Major General Claire Chennault. Thus, the best

confirmation that can be obtained on Boyington's record with the AVG is

that he scored 3.5 kills.

Whatever today's accounts show, Boyington returned to

the U.S. claiming to be one of America's first aces. He was perhaps the

first Marine aviator to have flown in combat against the Japanese,

though, and he felt he would easily regain his commission in the Marine

Corps. To his frustration, no one in any service seemed to want him. His

reputation was well known and this made his reception not exactly open

armed.

Boyington finally telegrammed his qualifications to

Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, and as a result, found himself back in

the Marine Corps on active duty as a Reserve major. He deployed as

executive officer of VMF-122 from the West Coast to the Solomons. He was

based at Espiritu Santo, initially flying squadron training, non-combat

missions. He deployed for a short but inactive tour at Guadalcanal in

March 1943, and after the squadron was withdrawn, he relieved Major

Elmer Brackett as commanding officer in April 1943. His first command

tour was disappointing. He eventually landed in VMF-112. which he

commanded for three weeks in the rear area. Prior to forward deployment,

he broke his leg while wrestling and was hospitalized.

|

|

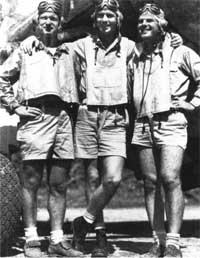

Black Sheep pilots scramble toward their F4U-1

"birdcage" Corsairs. The early model fighters had framed cockpit

canopies. The next F4U-1As and subsequent models used bubble canopies

which enhanced the limited visibility from the fighter's cockpit.

Author's

Collection

|

Boyington got another chance and took command of a

reconstituted VMF-214. The original unit had returned from a combat

tour, during which it had lost its commanding officer, Major William

Pace. When the squadron returned from a short rest and recreation tour

in Australia, the decision was made to reorganize the unit because the

squadron did not have a full complement of combat-ready pilots. Thus,

the squadron number went to a newly organized squadron under Major

Boyington. In his illuminating wartime memoir, Once They Were Eagles:

The Men of the Black Sheep Squadron, the squadron intelligence

officer, First Lieutenant Frank Walton, described how Boyington got the

new squadron command:

Major Boyington was the right rank for a squadron

commander; he was an experienced combat pilot; he was available; and the

need was great. These assets overcame such reservations as the general

[Major General Ralph J. Mitchell, Wing Commander of the 1st Marine

Aircraft Wing] may have had about his personal problems. General

[Mitchell] made the decision. "We need an aggressive combat leader.

We'll go with Boyington." The squadron had its commander.

Much has been written about Boyington and his

squadron. At 31, Boyington was older than his 22-year-old lieutenants.

His men called him "Gramps" or "Pappy." In prewar days, he was called

"Rats," after the Russian-born actor, Gregory Ratoff. The squadron

wanted to call themselves the alliterative "Boyington's Bastards," but

1940s sensitivities would not allow such language. They decided on the

more evocative "Black Sheep."

The popular image of VMF-214 as a collection of

malcontents and ne'er-do-wells is not at all accurate. The television

program of the late 1970s did nothing to dispel this inaccurate

impression. In truth, Pappy's squadron was much like any other fighter

squadron, with a cross-section of people of varying capabilities and

experience. The two things that welded the new squadron into such a

fearsome fighting unit was its new mount, the F4U-1 Corsair, and its

indomitable leader.

|

|

Pappy briefs his pilots before a mission from Espiritu

Santo. Front row, from left: Boyington, holding paper, Stanley R.

Bailey, Virgil G. Ray, Robert A. Alexander; standing, from left: William

N. Case, Rolland N. Rinabarger, Don H. Fisher, Henry M. Bourgeois, John

F. Begert, Robert T. Ewing, Denmark Groover, Jr., Burney L.

Tucker. Author's Collection

|

Boyington took his squadron to Munda on New Georgia

in September. On the 16th, the Black Sheep flew their first mission, a

bomber escort to Ballale, a Japanese airfield on a small island about

five miles southeast of Bougainville. The mission turned into a

free-for-all as about 40 Zeros descended on the bombers. Boyington

downed a Zero for his squadron's first kill. He quickly added four more.

Six other Black Sheep scored kills. It was an auspicious debut, marred

only by the loss of one -214 pilot, Captain Robert T. Ewing.

The following weeks were filled with continuous

action. Boyington and his squadron rampaged through the enemy

formations, whether the Marine Corsairs were escorting bombers, or

making pure fighter sweeps. The frustrated Japanese tried to lure Pappy

into several traps, but the pugnacious ace taunted them over the radio,

challenging them to come and get him.

|

|

Maintenance crews service this F4U-1 at a Pacific base.

The Corsair's size is shown to advantage in this view, as is the bubble

canopy of the late-production -1s and subsequent models. Author's

Collection

|

By mid-December 1943, VMF-214, along with the other

Allied fighter squadrons, began mounting large fighter sweeps staged

through the new fighter strip at Torokina Point on Bougainville. Author

Barrett Tillman described the state of affairs in the area at the end of

December 1943:

. . . Boyington and other senior airmen saw the

disadvantage of [these] large fighter sweeps. They intimidated the

opposition into remaining grounded, which was the opposite reaction

desired. A set of guidelines was drawn up for future operations. It

specified that the maximum number of fighters should be limited to no

more than 48. As few aircraft types and squadrons should be employed as

possible, for better coordination and mutual support.

This strategy was fine, except that Boyington was

beginning to feel the pressure that being a top ace seemed to bring.

People kept wondering when Pappy would achieve, then break, the magic

number of 26, Captain Eddie Rickenbacker's score in World War I. Joe

Foss had already equalled the early ace's total, but was now out of

action. Boyington scored four kills on 23 December 1943, bringing his

tally to 24. Boyington was certainly feeling the pressure to break

Rickenbacker's 25-year-old record. Boyington's intelligence officer,

First Lieutenant Frank Walton, wrote of his tenseness and quick flareups

when pressed about when and by how much he would surpass the magic

26.

A few days before his final mission, Boyington

reacted to a persistent public affairs officer. "Sure, I'd like to break

the record," said Boyington. "Who wouldn't? I'd like to get 40 if I

could. The more we can shoot down here, the fewer there'll be up the

line to stop us."

Later that night, Boyington told Walton, "Christ, I

don't care if I break the record or not, if they'd just leave me alone."

Walton told his skipper the squadron was behind him and that he was

probably in the best position he'd ever be in to break the record.

|

|

The

fighter strip at Torokina was hacked out of the Bougainville jungle.

This December 1943 view shows a lineup of Corsairs and an SBD, which is

completing its landing rollout past a grading machine still working to

finish the new landing field. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

74672

|

"You'll never have another chance," Walton said.

"It's now or never."

"Yes," Boyington agreed, "I guess you're right."

Like a melodrama, however, Boyington's life now

seemed to revolve around raising his score. Even those devoted members

of his squadron could not help wondering — if only to cheer their

squadron commander on — when he would do it.

Pappy's agony was about to come to a crashing halt.

He got a single kill on 27 December during a huge fight against 60

Zeros. But, after taking off on a mission against Rabaul on 2 January

1944, at the head of 56 Navy and Marine fighters, Boyington had problems

with his Corsair's engine. He returned without adding to his score.

The following day, he launched at the head of another

sweep staging through Bougainville. By late morning, other VMF-214

pilots returned with the news that Boyington had, indeed, been in

action. When they last saw him, Pappy had already disposed of one Zero,

and together with his wingman, Captain George M. Ashmun, was hot on the

tails of other victims.

The initial happy anticipation turned to apprehension

as the day wore on and neither Pappy nor Ashmun returned. By the

afternoon, without word from other bases, the squadron had to face the

unthinkable: Boyington was missing. The Black Sheep mounted patrols to

look for their leader, but within a few days, they had to admit that

Pappy was not coming back.

1stLt Robert M. Hanson of VMF-215 enjoyed a brief career

in which he shot down 20 of his final total of 25 Japanese planes in 13

days. He was shot down during a strafing run on 3 February, 1944, a day

before his 24th birthday. Department of Defense (USMC) 73114

|

Capt

Donald N. Aldrich was a 20-kill ace with VMF-2 15, and had learned to

fly with the Royal Canadian Air Force before the U.S. entered the war.

Although he survived the war, he was killed in a flying mishap in

1947. Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 72421

|

In fact, Boyington and his wingman had been shot down

after Pappy had bagged three more Zeros, thus bringing his claimed total

to 28, breaking the Rickenbacker tally, and establishing Boyington as

the top-scoring Marine ace of the war, and, for that matter, of all

time. However, these final victories were unknown until Boyington's

return from a Japanese prison camp in 1945. Boyington's last two kills

were thus unconfirmed. The only one who could have seen Pappy's

victories was his wingman, Captain Ashmun, shot down along with his

skipper. While there is no reason to doubt his claims, the strict rules

of verifying kills were apparently relaxed for the returning hero when

he was recovered from a prisoner of war camp after the war.

One

of Boyington's Black Sheep, 1stLt John F. Bolt, already an ace, shot

down his sixth plane over Rabaul in early January 1944. During the

Korean war, when he was flying as an exchange pilot with the Air Force,

he shot down six North Korean planes to become the Marine Corps first

jet ace. Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 72421

|

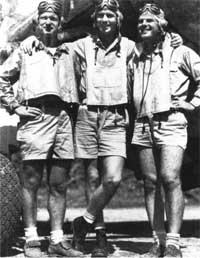

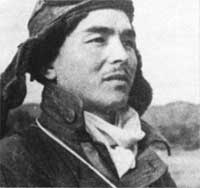

Three of the Corps' top aces pose at Torokina in early

1944. From left: 1stLt Robert Hanson, Capt Donald N. Aldrich, and Capt

Harold Spears were members of VMF-215 during the busy period following

the loss of Poppy Boyington. The three aviators accounted for a combined

total of 60 Japanese aircraft. Department of Defense (USMC) 73119

|

Pappy and his wingman had been overwhelmed by a swarm

of Zeros and had to bail out of their faltering Corsairs near Cape St.

George on New Ireland. Captain Ashmun was never recovered, but Boyington

was retrieved by a Japanese submarine after being strafed by the

vengeful Zeros that had just shot him down. Boyington spent the next 20

months as a prisoner of war, although no one in the U.S. knew it until

after V-J Day.

He endured torture and beatings during

interrogations, and was finally rescued when someone painted "Boyington

Here!" on the roof of his prison barracks. Aircraft dropping supplies to

the prisoners shortly after the ceasefire in August 1945 spotted the

message and soon everyone knew that Pappy was coming back.

Although he had never received a single decoration

while he was in combat, Boyington returned to the U.S. to find that he

not only had been awarded the Navy Cross, but the Medal of Honor as

well, albeit "posthumously."

With Pappy Boyington gone, several other young Marine

aviators began to make themselves known. The most productive, and

unfortunately, the one with the shortest career, was First Lieutenant

Robert M. Hanson of VMF-215. Although born in India of missionary

parents, Hanson called Massachusetts home. A husky, competitive man, he

quickly took to the life of a Marine combat aviator.

During his first and second tours, flying from Vella

Lavella with other squadrons, including Boyington's Black Sheep, Hanson

shot down five Japanese planes, although during one of these fights, he,

himself, was forced to ditch his Corsair in Empress Augusta Bay.

Capt

Harold L. Spears was Robert Hanson's flight leader on the day Hanson was

shot down and killed after Spears gave Hanson permission to make a

strafing run against a Japanese position in December 1944. Department of Defense

Photo (USMC) 72424

|

On

30 June 1943, 1stLt Wilbur J. Thomas of VMF-213 shot down four enemy

planes while providing air cover for American operations on New Georgia.

Two weeks later. on 15 July, he shot down three more Japanese bombers.

Before he left the Pacific, his total of kills was 18-1/2. Department of Defense

Photo (USMC) 58384

|

For his third tour, he joined VMF 215 at Torokina. By

mid-January, Hanson had begun such a hot streak of kills, that the young

pilot had earned the name "Butcher Bob." Hanson shot Japanese planes

down in bunches. On 18 January 1944, he disposed of five enemy aircraft.

On 24 January, he added four more Zeros. Another four Japanese planes

went down before Hanson's Corsair on 30 January. His score now stood at

25, 20 of which had been gained in 13 days in only six missions.

Hanson's successes were happening so quickly that he was relatively un

known outside his combat area. Very few combat correspondents knew of

his record until later.

Lieutenant Hanson took off for a mission on 3

February 1944. The next day would be his 24th birthday, and the

squadron's third tour would end in a few days. He was going back home.

He called his flight commander, Captain Harold L. Spears, and asked if

he could strafe Japanese antiaircraft artillery positions at Cape St.

George on New Ireland, the same general area over which Pappy Boyington

had been shot down a month before.

Hanson made his run, firing his plane's six

.50-caliber machine guns. The Japanese returned fire as the big,

blue-gray Marine fighter rocketed past, seemingly under control.

However, Hanson's plane dove into the water from a low altitude, leaving

only an oil slick.

Hanson's meteoric career saw him become the

highest-scoring Marine Corsair ace, and the second Marine high-scorer,

one behind Joe Foss. Lieutenant Hanson received a posthumous Medal of

Honor for his third tour of combat. As Barrett Tillman points out in his

book on the F4U, Hanson "became the third and last Corsair pilot to

receive the Medal of Honor in World War II. And the youngest."

|

Japanese Pilots in the Solomons Air War

The stereotypical picture of a small, emaciated

Japanese pilot , wearing glasses whose lenses were the thickness of the

bottoms of Coke bottles, grasping the stick of his bamboo-and-rice-paper

airplane (the design was probably stolen from the U.S., too) did not

persist for long after the war began. The first American aircrews to

return from combat knew that they had faced some of the world's most

experienced combat pilots equipped with some pretty impressive

airplanes.

|

|

A

rebuilt late-model Zero shows off the clean lines of the A6M series,

which changed little during the production run of more than 10,000

fighters. Author's Collection

|

Certainly, Japanese society was completely alien to

most Americans. Adherence to ancestral codes of honor and a national

history — one of constant internal, localized strife where personal

weakness was not tolerated, especially in the Samurai class of

professional warriors — did not permit the individual Japanese

soldier to surrender even in the face of overwhelming odds.

|

|

Newly commissioned Ens Junichi Sasai in May 1941.

Author's

Collection

|

This capability did not come by accident. Japanese

training was tough. In some respects, it went far beyond the legendary

limits of even U.S. Marine Corps boot training. However, as the war

turned against them, the Japanese relaxed their stringent prewar

requirements and mass-produced pilots to replace the veterans who were

lost at Midway and in the Solomons. For instance, before the war, pilots

learned navigation and how to pack a parachute. After 1942, these

subjects were eliminated from training to save time.

Young men who were accepted for flight training were

subjected to an excruciating preflight indoctrination into military

life. Their instructors — mostly enlisted — were literally

their rulers, with nearly life-or-death control of the recruits'

existence. After surviving the physical training, the recruits began

flight training where the rigors of their preflight classes were

maintained. By the time Japanese troops evacuated Guadalcanal in

February 1943, however, their edge had begun wearing thin as they had

lost many of their most experienced pilots and flight commanders, along

with their aircraft.

The failed Japanese adventure at Midway in June 1942,

as well as the heavy losses in the almost daily combat over Guadalcanal

and the Solomons deprived them of irreplaceable talent. Even the most

experienced pilots eventually came up against a losing roll of the

dice.

As noted in the main text, Japanese aces such as

Sakai, Sasai, and Ota were invalided out of combat, or eventually

killed. Rotation of pilots out of the war zone was a system employed

neither by the Japanese nor the Germans, as a matter of fact. As several

surviving Axis aces have noted in their memoirs, they flew until they

couldn't. Indeed many Japanese and German aces flew until 1945 — if

they were lucky enough to survive — accumulating incredible numbers

of sorties and combat hours, as well as high scores which doubled and

tripled the final tallies of their American counterparts.

Unfortunately, Japanese records are not as complete

as Allied histories, perhaps because of the tremendous damage and

confusion wrought by the U.S. strategic bombing during the last year of

the war. Thus, certainly Japanese scores are not as firm as they are for

Allied aviators.

In the popularly accepted sense, the Japanese did not

have "aces." Those pilots who achieved high scores were referred to as

Gekitsui-O (Shoot-Down Kings). A pilot's report of his successes was

taken at face value, without a confirmation system such as required by

the Allies. Without medals or formal recognition, it was believed that

there was little need for self-promotion. Fighters did not have gun

cameras, either. Japanese air strategy was to inflict as much damage as

possible without worrying about confirming a kill. (This outwardly

cavalier attitude about claiming victories is somewhat suspect since

many Zeros carried large "scoreboards" on their tails and fuselages.

These markings might have been attributed to the aircraft rather than to

a specific pilot.)

|

|

A

lineup of A6M2 Zeros at Buin in 1943. By this time, the heavy combat

over Guadalcanal had been replaced by engagements with Marine Corsairs

over the approaches to Bougainville. Japanese Navy aircraft occasionally

flew from land bases, as these Zeros, although they are actually

assigned to the carrier Zuikaku. Author's Collection

|

The Aces

Although the men in the Zeros were probably much like

— at least in temperament — Marine Wildcat and Corsair pilots

they opposed, the Imperial Japanese Navy pilots had an advantage: many

of them had been flying combat for perhaps a year — maybe longer

— before meeting the untried American aviators over Guadalcanal in

August 1942. Saburo Sakai was severely wounded during an engagement with

U.S. Navy SBDs on the opening day of the invasion. He returned to Japan

with about 60 kills to his credit. Actually, because he was so badly

wounded early in the Guadalcanal fighting, Sakai never got a chance to

engage Marine Corps pilots. They were still in transit to the Solomons

two weeks after Sakai had been invalided home. (His commonly accepted

final score of 64 is only a best guess, even by his own logbook.)

|

|

Enlisted pilots of the Tainan Kokutai pose at Rabaul in

1942. Several of these aviators would be among the top Japanese aces,

including Saburo Sakai (middle row, second from left), and Hiroyoshi

Nishizawa (standing, first on left). Author's Collection

|

After graduating from flight training, Sakai joined a

squadron in China flying Mitsubishi Type 96 fighters, small,

open-cockpit, fixed-landing-gear fighters. As a third-class petty

officer, Sakai shot down a Russian built SB-3 bomber in October 1939. He

later joined the Tainan Kokutai (Tainan air wing), which would be come

one of the Navy's premier fighter units, and participated in the Pacific

war's opening actions in the Philippines.

A colorful personality, Sakai was also a dedicated

flight leader. He never lost a wingman in combat, and also tried to pass

on his hard-won expertise to more junior pilots. After a particularly

unsuccessful mission in April 1942, where his flight failed to bring

down a single American bomber from a flight of seven Martin B-26

Marauders, he sternly lectured his pilots about maintaining flight

discipline instead of hurling them selves against their foes. His words

had great effect — Sakai was respected by subordinates and

superiors alike — and his men soon formed a well-working unit,

responsible for many kills in the early months of the Pacific war.

Typically, Junichi Sasai, a lieutenant, junior grade,

and one of Sakai's young aces with 27 confirmed kills, was posthumously

promoted two grades to lieutenant commander. This practice was common

for those Japanese aviators with proven records, or high scores, who

were killed during the war. Japan was unique among all the combatants

during the war in that it had no regular or defined system of awards,

except for occasional inclusion in war news — what the British

might call being "mentioned in dispatches."

This somewhat frustrating lack of recognition was

described by Masatake Okumiya, a Navy fighter commander, in his classic

book Zero! (with Jiro Horikoshi). Describing a meeting with

senior officers, he asked them, "Why in the name of heaven does

Headquarters delay so long in according our combat men the honors they

deserve?. . .Our Navy does absolutely nothing to recognize its

heroes..."

LCdr

Tadashi Nakajima, who led the Tainan Air Group, was typical of the more

senior aviators. His responsibilities were largely administrative but he

tried to fly missions whenever his schedule permitted, usually with

unproductive results. He led several of the early missions over

Guadalcanal and survived to lead a Shiden unit in 1944. It is doubtful

that Nakajima scored more than 2 or 3 kills. Author's Collection

|

Lt

(j.g.) Junichi Sasai of the Tainan Air Group. This 1942 photo shows the

young combat leader, of such men as Sakai and Nishizawa. shortly before

his death over Guadalcanal. Author's Collection

|

Occasionally, senior officers would give gifts, such

as ceremonial swords, to those pilots who had performed great services.

And sometimes, superiors would try to buck the unbending system without

much success. Saburo Sakai described one instance in June 1942 where the

captain in charge of his wing summoned him and Lieutenant Sasai to his

quarters.

Dejectedly, the captain told his two pilots how he

had asked Tokyo to recognize them for their great accomplishments.

"...Tokyo is adamant about making any changes at this time," he said.

"They have refused even to award a medal or to promote in rank." The

captain's deputy commander then said how the captain had asked that

Sasai be promoted to commander — an incredible jump of three grades

— and that Sakai be commissioned as an ensign.

Perhaps one of the most enigmatic, yet enduring,

personalities of the Zero pilots was the man who is generally

acknowledged to be the top-scoring Japanese ace, Hiroyoshi Nishizawa.

Saburo Sakai described him as "tall and lanky for a Japanese, nearly

five feet, eight inches in height," and possessing "almost supernatural

vision."

|

|

These A6M3s are from the Tainan Air Group, and several

sources have identified aircraft 106 as being flown by top ace

Nishizawa. Typically, these fighters carry a single centerline fuel

tank. The Zero's range was phenomenal, sometimes extending to nearly

1,600 miles, making for a very long flight for its exhausted

pilots. Photo courtesy of Robert Mikesh

|

Nishizawa kept himself usually aloof, enjoying a

detached but respected status as he rolled up an impressive victory

tally through the Solomons campaign. He was eventually promoted to

warrant officer in November 1943. Like a few other high-scoring aces,

Nishizawa met death in an unexpected manner in the Philippines. He was

shot down while riding as a passenger in a bomber used to transport him

to another base to ferry a Zero in late October 1944. In keeping with

the established tradition, Nishizawa was posthumously promoted two ranks

to lieutenant junior grade. His score has been variously given as 102,

103, and as high as 150.

However, the currently accepted total for him is

87.

Henry Sakaida, a well-known authority on Japanese

pilots in World War II, wrote:

No Japanese pilot ever scored more than 100

victories! In fact, Nishizawa entered combat in 1942 and his period of

active duty was around 18 months. On the other hand, Lieutenant junior

grade Tetsuo Iwamoto fought from 1938 until the end of the war. If there

is a top Navy ace, it's him.

Iwamoto claimed 202 victories, many of which were

against U.S. Marine Corps aircraft, including 142 at Rabaul. I don't

believe his claims are accurate, but I don't believe Nishizawa's total

of 87, either. (I might believe 30.) Among Iwamoto's claims were 48

Corsairs and 48 SBDs! His actual score might be around 80.

Several of Sho-ichi Sugita's kills — which are

informally reckoned to total 70 — were Marine aircraft. He was

barely 19 when he first saw combat in the Solomons. (He had flown at

Midway but saw little of the fighting.) Flying from Buin on the southern

tip of Bougainville. he first scored on 1 December 1942, against a USAAF

B-17. Sugita was one of the six Zero escort pilots that watched as P-38s

shot down Admiral Yamamoto's Betty on 18 April 1943. There was little

they could do to alert the bombers carrying the admiral and his staff

since their Zeros' primitive radios had been taken out to save

weight.

The problem of keeping accurate records probably came

from the directive issued in June 1943 by Tokyo forbidding the recording

of individual records, the better to foster teamwork in the seemingly

once-invincible Zero squadrons. Prior to the directive, Japanese Zero

pilots were the epitome of the hunter-pilots personified by the World

War I German ace, Baron Manfred von Richthofen. The Japanese Navy pilots

roamed where they wished and attacked when they wanted, assured in the

superiority of their fighters.

Occasionally, discipline would disappear as flight

leaders dove into Allied bomber formations, their wingmen hugging their

tails as they attacked with their maneuverable Zeros, seemingly

simulating their Samurai role models whose expertise with swords is

legendary.

Petty Officer Hiroyoshi Nishizawa at Lae, New Guinea, in

1942. Usually considered the top Japanese ace, Navy or Army. A

definitive total will probably never be determined. Nishizawa died while

flying as a passenger in a transport headed for the Philippines in

October 1944. The transport was caught by American Navy Hellcats, and

Lt(j.g.) Harold Newell shot it down. Author's Collection

|

Petty Officer Sadamu Komachi flew throughout the Pacific

War, from Pearl Harbor to the Solomons, from Bougainville to the defense

of the Home Islands. His final score was 18. Photo courtesy of Henry

Sakaida

|

Most of the Japanese aces, and most of the

rank-and-file pilots, were enlisted petty officers. In fact, no other

combatant nation had so many enlisted fighter pilots. The U.S. Navy and

Marine Corps had a relatively few enlisted pilots who flew in combat in

World War II and for a short time in Korea. Britain and Germany had a

considerable number of enlisted aviators without whose services they

could not have maintained the momentum of their respective

campaigns.

However, the Japanese officer corps was relatively

small, and the number of those commissioned pilots serving as combat

flight commanders was even smaller. Thus, the main task of fighting the

growing Allied air threat in the Pacific fell to dedicated enlisted

pilots, many of them barely out of their teens.

During a recent interview, Saburo Sakai shed light on

the role of Japanese officer-pilots. He said:

They did fight, but generally, they were not very

good because they were inexperienced. In my group, it would be the

enlisted pilots that would first spot the enemy. The first one to see

the enemy would lead and signal the others to follow. And the officer

pilot would be back there, wondering where everyone went! In this sense,

it was the enlisted pilots who led, not the officers.

|

|