|

TIME OF THE ACES: Marine Pilots in the Solomons

by Commander Peter B. Mersky, U.S. Naval Reserve

Guadalcanal: The Beginning of the Long Road Back

Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 23, the initial air unit

participating in the Guadalcanal operation, was assigned the mission of

supporting the ground operations of the 1st Marine Division as well the

air defense of the island once the landing had been made. MAG-23

included VMF-223 and -224, and VMSB-231 and -232. The fighter squadrons

flew the F4F-4, the Grumann Wildcat with folding wings and six

wing-mounted .50-caliber machine guns. The two VMSBs flew the Douglas

SBD-3 Dauntless dive-bomber. Another fighter squadron, VMF-212, under

Major Harold W. Bauer, was on the island of Efate in the New Hebrides,

while MAG-23 headquarters had yet to sail from Hawaii by the time

Marines hit the beaches on 7 August 1942. The first contingent of MAG-23

— VMF-223 and VMSB-232 — left Hawaii on board the escort

carrier USS Long Island (CVE 1). On 20 August, 200 miles from

Guadalcanal, the two squadrons launched toward their new home. VMF-224

(Captain Robert E. Galer) and VMSB-231 (Major Leo R. Smith) followed in

the aircraft transports USS Kitty Hawk (APV 1) and USS

Hammondsport (APV 2), and flew on to the island on 30 August.

While en route toward the launch point for Guadalcanal, Captain Smith

wisely decided to trade eight of his less experienced junior pilots for

eight pilots of VMF-212 who had more flight time and training in the F4F

than had Smith's fledglings.

|

|

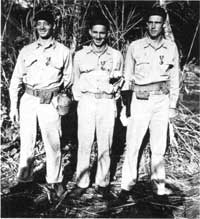

The

Douglas SBD Dauntless divebomber fought in nearly every theater, flying

with the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, as well as the U.S. Army (as the

A-24 Banshee). The SBD made its reputation in the Pacific, especially at

Midway and Guadalcanal. Author's Collection

|

The newly arrived squadrons barely had time to get

settled before they were in heavy action. Early on the 21st, the

Japanese sent a 900-man force to attack Henderson Field, named after

Major Lofton R. Henderson, a dive-bomber pilot killed at Midway. Around

mid-day, Captain Smith was leading a four-plane patrol north of Savo

Island heading to ward the Russell Islands with Second Lieutenants Noyes

McLennan and Charles H. Kendrick, and Technical Sergeant John Lindley.

The two lieutenants had 16 days of operational flight training in F4Fs,

and Lindley had been through ACTG, the Aircraft Carrier Training Group,

which, as part of its training syllabus, gave tyro pilots indoctrination

into fighter tactics.

Beyond Savo, six Zeros came straight at them from the

north, with an altitude advantage of 500 feet. Smith recognized the

Zeros immediately, although neither he nor any of the other three pilots

had ever seen one before. He turned his flight toward them and the Zeros

headed toward the F4Fs.

It was hard to say just what happened next except

that the Zero Smith was shooting at pulled up and he shot fairly well

into the belly of the enemy plane as it went by, only to find that now

he had two Zeros on his tail. Captain Smith dove toward Henderson Field

and the Japs broke away.

|

|

Members of VMF-224 pose by one of their fighters on

Guadalcanal in mid-September 1942. Rear row, left to right: 2dLt George

L. Hollowell, SSgt Clifford D. Garrabrant, 2dLt Robert A Jefferies, Jr.,

2dLt Allan M. Johnson, 2dLt Matthew H. Kennedy, 2dLt harles H. Kunz,

2dLt Dean S. Hartley, Jr., MG William R. Fuller. Front row: 2dLt Robert

M. D'Arcy, Capt Stanley S. Nicolay, Maj John F Dobbin, Maj Robert E.

Galer, Maj Kirk Armistead, Capt Dale D. Irwin, 2dLt Howard L. Walter,

2dLt Gordon E. Thompson. All in this picture are pilots except MG

Fuller, who was the Engineering Officer. Lt Thompson was reported

missing in action on 31 August 1942. Photo courtesy of BGen Robert E.

Galer

|

Minutes later, the Zero Captain Smith shot became

VMF-223's first kill when it crashed into the water just off Savo

Island. Smith's plane had some bullet holes but was flying alright. Two

F4Fs joined on him. They looked back and it appeared that the Zeros were

in a dogfight near Savo. The Marines thought they were ganging up on

Sergeant Lindley so they went back to help him, but found that there was

no F4F, just five Zeros acting like they were fighting.

The three Marines then got into another dogfight and

the Zeros shot them up some more. Lindley and Kendrick got back to

Henderson and made dead-stick landings. Lindley was burned and blinded

by hot oil when his oil tank was shattered and landed wheels up.

Kendrick's oil line was shot away and he crash-landed. His airplane

never flew again. It took eight days before Smith's plane was patched up

enough to fly once again. Repairs on the fourth plane required 10 days.

Only 15 of the 19 F4Fs were flyable after their first day of action from

Henderson Field.

Marion Carl, now assigned to VMF-223, shot down three

Japanese aircraft on 24 August to become the Marine Corps' first ace.

Carl added two more kills on the 26th. The young fighter pilot found

himself in competition with his squadron commander, as John Smith also

began accumulating kills with regularity.

Capt

Henry T. Elrod, a Wildcat pilot with VMF-211, earned what is

chronologically the first Marine Corps — but not the first actually

awarded — Medal of Honor for World War II. His exploits during the

defense of Wake Island were not known until after the war. After his

squadron's aircraft were all destroyed, Capt Elrod fought on the ground

and was finally killed by a Japanese rifleman. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

26044

|

Three personalities of the Cactus Air Force pose after

receiving the Navy Cross from Adm Nimitz on 30 September 1942. From

left: Maj John L. Smith, Maj Robert E. Galer, and Capt Marion E.

Carl. Photo courtesy or Capt Stanley S. Nicolay

|

|

'CUB One' at Guadalcanal

On 8 August 1942, U.S. Marines captured a nearly

completed enemy airstrip on Guadalcanal, which would prove critical to

the success of the island campaign. It was essential that the airstrip

become operational as quickly as possible, not only to contest enemy

aircraft in the skies over Guadalcanal, but also to ensure that badly

needed supplies could be flown in and wounded Marines flown out. As it

turned out, Henderson Field also proved to be a safe haven for Navy

planes whose carriers had been sunk or badly damaged.

A Marine fighter squadron (VMF-223) and a Marine dive

bomber squadron (VMSB-232) were expected to arrive on Guadalcanal around

16 August. Unfortunately, Marine aviation ground crews scheduled to

accompany the two squadrons to Guadalcanal were still in Hawaii, and

would not arrive on the island for nearly two weeks. Aircraft ground

crews were urgently needed to service the two Marine squadrons upon

their arrival.

The nearest aircraft ground crews to Guadalcanal were

not Marines, but 450 Navy personnel of a unit known as CUB One, an

advanced base unit consisting of the personnel and material necessary

for the establishment of a medium-sized advanced fuel and supply base.

CUB One had only recently arrived at Espiritu Santo in the New

Hebrides.

On 13 August, Admiral John S. McCain ordered Marine

Major Charles H. "Fog" Hayes, executive officer of Marine Observation

Squadron 251, to proceed to Guadalcanal with 120 men of CUB One to

assist Marine engineers in completing the airfield (recently named

Henderson Field in honor of a Marine pilot killed in the Battle of

Midway), and to serve as ground crews for the Marine fighters and dive

bombers scheduled to arrive within a few days. Navy Ensign George W.

Polk was in command of the 120-man unit, and was briefed by Major Hayes

concerning the unit's critical mission. (After the war, Polk became a

noted newsman for the Columbia Broadcasting System, and was murdered by

terrorists during the Greek Civil War. A prestigious journalism award

was established and named in his honor).

Utilizing four destroyer transports of World War I

vintage, the 120-man contingent from CUB One departed Espiritu Santo on

the evening of 13 August. The total supply carried northward by the four

transports included 400 drums of aviation gasoline, 32 drums of

lubricant, 282 bombs (100 to 500 pounders), belted ammunition, a variety

of tools, and critically needed spare parts.

The echelon arrived at Guadalcanal on the evening of

15 August, unloaded its passengers and supplies, and began assisting

Marine engineers the following morning on increasing the length of

Henderson Field. In spite of daily raids by Japanese aircraft, the

arduous work continued, and on 19 August, the airstrip was completed.

CUB One personnel also installed and manned an air-raid warning system

in the famous "Pagoda," the Japanese-built control tower.

|

|

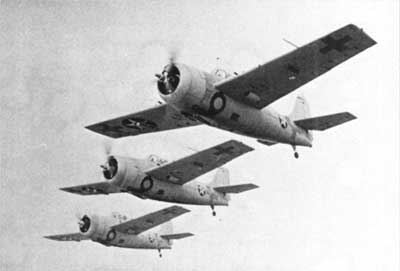

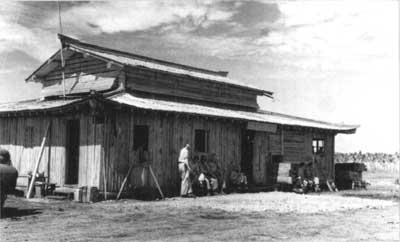

Allied air operations in the Solomons were controlled

from the "Pagoda," built by the Japanese and rehabilitated by the men of

CUB One. Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 51812

|

On 20 August, 19 planes of VMF-223 and 12 dive

bombers of VMSB-232 were launched from the escort carrier Long

Island and arrived safely at Henderson Field. The Marine pilots were

quickly put into action over the skies of Guadalcanal in combat

operations against enemy aircraft.

The men of CUB One performed heroics in servicing the

newly arrived Marine fighters and bombers. Few tools existed or had yet

arrived to perform many of the aircraft servicing jobs to which CUB One

was assigned. It was necessary to fuel the Marine aircraft from

55-gallon drums of gasoline. As there were no fuel pumps on the island,

the drums had to be man-handled and tipped into the wing tanks of the

SBDs and the fuselage tanks of the F4F fighters. To do this, CUB One

personnel stood precariously on the slippery wings of the aircraft and

sloshed the gasoline from the heavy drums into the aircraft's gas tanks.

The men used a make-shift funnel made from palm-log lumber.

Bomb carts or hoists were also at a premium during

the early days of the Guadalcanal campaign, so aircraft bombs had to be

raised by hand to the SBD drop brackets, as the exhausted, straining men

wallowed in the mud beneath the airplanes.

No automatic belting machines were available at this

time as well, so that the .50-caliber ammunition for the four guns on

each fighter had to be hand-belted one round at a time by the men of CUB

One. The gunners on the dive bombers loaded their ammunition by the same

laborious method.

The dedicated personnel of CUB One performed these

feats for 12 days before Marine squadron ground crews arrived with the

proper equipment to service the aircraft. The crucial support provided

by CUB One was instrumental to the success of the "Cactus Air Force" on

Guadalcanal.

Like their Marine counterparts, the personnel of CUB

One suffered from malaria, dengue fever, sleepless nights, and the

ever-present shortage of food, clothing, and supplies. They would remain

on Guadalcanal, performing their duties in an exemplary manner, until

relieved on 5 February 1943. CUB One richly earned the Presidential Unit

Citation awarded to the unit for its gallant participation in the

Guadalcanal campaign.

—Arvil L. Jones with Robert V. Aquilina

|

The 30th was a busy day for the Marine fighters on

Guadalcanal. The previous day's action saw eight Japanese aircraft shot

down. However, by now, six of VMF-223's original complement of 19

Wildcats had also been destroyed or put out of action. The combat had

been fast and furious since Smith and his squadron had arrived only nine

days before. His young pilots were learning, but at a price.

One of the squadrons that shared Henderson Field with

the Marines was the 67th Fighter Squadron, a somewhat orphaned group of

Army Air Corps pilots, who had arrived on 22 August, led by Captain Dale

Brannon, and their P-400 Airacobras, an export version of the Bell P-39.

Despite its racy looks, the Airacobra found it difficult to get above

15,000 feet, where much of the aerial combat was taking place.

The 67th had had a miserable time of it so far

because of their plane's poor performance, and morale was low. The

pilots were beginning to question their value to the overall effort, and

their commander, desperate for any measure of success to share with his

men, asked Captain Smith if he and his squadron could accompany the

Marines on their next scramble. Smith agreed and on 30 August, the

Marine and Army fighters — eight F4Fs and seven P-400s —

launched for a lengthy combat air patrol.

The fighters rendezvoused north of Henderson,

maintaining 15,000 feet because of the P-400s' lack of oxygen.

Coastwatchers had identified a large formation of Japanese bombers

heading toward Henderson but had lost sight of their quarry in the

rapidly building wall of thunderclouds approaching the island. The

defenders orbited for 40 minutes, watching for the enemy bombers and

their escorts.

Suddenly, Captain Smith saw the seven Army fighters

dive toward the water, in hot pursuit of Zeros that had emerged from the

clouds. The highly maneuverable Zeros quickly turned the tables on the

P-400s, however. As the Japanese fighters concentrated on the hapless

Bells, the Marine Wildcats lined up behind the Zeros and quickly shot

down four of the dark green Mitsubishis. The effect of the F4Fs' heavy

machine guns was devastating.

Making a second run, Captain Smith found himself

going head-to-head with a Zero, its pilot just as determined as his

Marine opponent. Smith's guns finally blew the Zero up just before a

collision or before one of the two fighter pilots would have had to turn

away. By the end of the engagement, John Smith had shot down two more

Zeros for a total of four kills. With nine kills, Smith was the leading

Marine Corps ace at the time. Fourteen Japanese fighters — the

bombers they were escorting had turned back — had been shot down by

the Marine and Army pilots, although four of the P-400s were also

destroyed. Two of the pilots returned to Guadalcanal; two did not.

|

|

A

profile of Bell P-39 Airacobra by Larry Lapadura. "Short Stroke"

operated from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal from late 1942 to early

1943. The aircraft's deceptively streamlined shape belied a mediocre

performance, especially above 15,000 feet. However, the aircraft was

well armed and used with success as a ground strafer. Author's

Collection

|

The Marine fighter contingent at Guadalcanal was now

down to five operational aircraft; it needed rein forcement immediately.

Help was on the way, however, for VMF-224 arrived in the afternoon of

the 30th, after John Smith and his tired, but elated squadron returned

from their frantic encounter with the Japanese fighter force. For their

first few missions, VMF-224's pilots accompanied the now-veteran Rainbow

Squadron pilots of VMF223.*

* When it was first established

on 1 May 1942, VMF-223 was called the "Rainbow" Squadron. In May 1943,

it changed its nickname to the more Marine-like

"Bulldogs."

|

|

Maj

John L. Smith poses in a Wildcat after returning to the States. A tough,

capable combat leader, Smith received the Medal of Honor for his service

at Guadalcanal. Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 11984

|

Captain Galer's VMF-224 had no time to acclimate to

its new base. (The day after its arrival, it was in action.) The

squadron landed on the 30th in the midst of an alert, and was quickly

directed to its parking areas on the field.

The next two weeks saw several of the Marine aviators

bail out of their Wildcats after tangling with the enemy Zeros. On 31

August, First Lieutenant Stanley S. Nicolay of VMF-224 was on a flight

with Second Lieutenant Richard R. Amerine, Second Lieutenant Charles E.

Bryans, and Captain John F. Dobbin, the squadron executive officer. It

was VMF-224's first combat mission since its arrival the day before. As

the Marines struggled past 18,000 feet on their way up to 20,000,

Lieutenant Nicolay noticed two of the wingmen lagging farther and

farther back.

He called Amerine and Bryans but got no response. He

then called Dobbin and said he wanted to drop back to check on the

wayward Wildcats. "It's too late to break up the formation," Dobbin

wisely said. "There's nothing we can do." Nicolay closed up on Dobbin

and they continued on.

The two young aviators had problems with their

primitive oxygen systems and lacking sufficient oxygen, they possibly

had even passed out in the thin air. Nicolay recalled,

We never saw Bryans again. It was so senseless. I

remember thinking that after all their training and effort, neither one

of them ever fired a shot in anger. They had no chance. The oxygen

system was just a tiny, white triangular mask that fitted over the nose

and mouth. You turned on the bottle, and that was it. No pressure

system, nothing.

Apparently, the two Marine pilots had been jumped by

roving Zeros. Bryans was thought to be killed almost immediately, while

Amerine was able to bail out. He parachuted to the relative safety of

the jungle, and as he attempted to return to Henderson Field, he

encountered several Japanese patrols on the way back, killing four enemy

soldiers before returning to the Marine lines.

|

|

1stLt Stanley S. Nicolay beside a Wildcat, probably just

before deploying to the Pacific in 1942. He eventually shot down three

Betty bombers at Guadalcanal. Note the narrow track of the Wildcat's

main landing gear. Photo courtesy of Capt Stanley S. Nicolay

|

Marion Carl, who had 11 kills, had his own

escape-and-evasion experience after he and his wingman, Lieutenant

Clayton M. Canfield, were shot down on 9 September. Carl bailed out of

his burning Wildcat and landed in the water where a friendly native

scooped him up and hid him from the roving Japanese patrols. (Canfield

had been quickly rescued by an American destroyer.)

The native took the ace to a native doctor who spoke

English. The doctor gave Carl a small boat with an old motor which

needed some work before it functioned properly With the Japanese army

all around, it was important that the American pilot get out as soon as

he could.

Finally, he and the doctor arrived offshore of Marine

positions on Guadalcanal. Dennis Byrd recalled Carl's return on the

afternoon of 14 September:

A small motor launch operated by a very black native

with a huge head of frizzled hair pulled up to the Navy jetty at Kukum.

The tall white man tending the boat's wheezing engine was VMF-223's

Captain Marion Carl. He had been listed as missing in action since

September 9th and was presumed dead... Carl reported that on the day he

disappeared, he'd shot down two more Jap bombers. Captain Carl's score

was now 12 and Major Smith's, 14.

Now-Major Galer scored his squadron's first kills

when he shot down two Zeros during a noontime raid of 26 bombers and

eight Zero escorts over Henderson on 5 September. VMF-224 went up to

intercept them, and the squadron commander knocked down a bomber and a

fighter, after which he was shot down by a Zero that tacked onto him

from behind and riddled his Wildcat. Recalling the action in a wartime

press release, Galer said:

|

|

A

rare photo of an exuberant LtCol Bauer as he demonstrates his technique

to two ground crewmen. Intensely competitive, and known as "the Coach,"

Bauer was one of several Marine Corps aviators who received the Medal of

Honor, albeit posthumously, at Guadalcanal. National Archives photo 208-PU-14X-1

PNT

|

l knew I'd be forced to land, but that Zero getting

me dead to rights made me sore. I headed into a cloud, and instead of

coming out below it as he expected, I came out on top and let him have

it. . . .

Then we both fell, but he was in flames and done for.

I made a forced landing in a field, and before my wheels could stop

rolling, Major Rivers J. Morrell and Lieutenant Pond of VMF-223, both

forced their ships on the same deck — all within three minutes of

each other!

Two days after his forced landing, Major Galer had to

ditch his aircraft once more after another round with the Japanese. His

flight was returning from a mission when it ran into a group of enemy

bombers. He related that:

One of them fell to my guns, and pulling out of the

dive, I took after a Zero. But I didn't pull around fast enough, and his

guns knocked out my engine, setting it on fire. We were at about 5,000

feet, but l feared the swirling mass of Japs more than the fire . . . so

I laid over on my back and dove headlong for some clouds below me.

Coming through the clouds, I didn't see any more Japs, and leveled off

at 2,000 feet. I changed my angle of flight and grade of descent so I'd

land as near as possible to shore. I set down in the drink some 200 or

300 yards from shore and swam in, unhurt.*

*This was not the first time Galer had a watery end

to a flight. As a first lieutenant with VMF-2 in 1940, he had to ride

his Grumman F3F biplane fighter in while approaching the carrier

Saratoga (CV3). The Grumman sank and stayed on the bottom off San

Diego for 40 years. It was discovered by a Navy exploration team and

raised, somewhat the worse for wear. Retired Brigadier General Robert

Galer was at the dock when his old mount found dry land once

more.

|

The Aircraft in the Conflict

The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps were definitely at a

disadvantage when America entered World War II in December 1941. Besides

other areas, their frontline aircraft were well behind world

standards.

The Japanese did not suffer similarly, however, for

they were busy building up their arsenal as they sought sources of raw

materials they needed and were prepared to go to war to acquire. Besides

possessing what was the finest aerial torpedo in the world — the

Long Lance — they had the aircraft to deliver it. And they had

fighters to protect the bombers. Although the world initially refused to

believe how good Japanese aircraft and their pilots were, it wasn't long

after the attack on Pearl Harbor that reality seeped in.

|

|

The

first production model of Grumman's stubby, little Wildcat was the

F4F-3, which carried four .50-caliber machine guns in the wings. Its

wings did not fold, unlike the -4 which added two more machine guns and

folding wings. These F4F-3s of VMF-121 carry prewar exercise

markings. Author's Collection

|

In many respects, the U.S. Army Air Force — it

had been the U.S. Army Air Corps until 20 June 1941 — and the Navy

and Marine Corps had the same problems in the first two years of the

war. The Army's top fighters were the Bell P-39 Airacobra and the

Curtiss P-40B/E Tomahawk/Kittyhawk. The Navy and Marine Corps' two

frontline fighters were the Brewster F2A-3 Buffalo and the Grumman

F4F-3/4 Wildcat during 1942.

Of these single-seaters, only the Army's P-40 and the

Navy's F4F achieved any measure of success against the Japanese in 1942.

The P-40's main attributes were its diving speed, which let it disengage

from a fight, and its ability to absorb punishment and still fly, a

confidence builder for its hard-pressed pilots. The Wildcat was also a

tough little fighter ("built like Grumman iron" was a popular

catch-phrase of the period), and had a devastating battery of four (for

the F4F-3) or six .50-caliber machine guns (for the F4F-4) and a fair

degree of maneuverability.

Both the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy also had

outstanding aircraft. The Army's primary fighter of the early war was

the Nakajima K.43 Hayabusa (Peregrine Falcon), a light, little aircraft,

with a slim, tapered fuselage and a bubble canopy.

The Navy's fighter came to symbolize the Japanese air

effort, even for the Japanese, themselves. The Mitsubishi Type "O"

Carrier Fighter (its official designation) was as much a trend-setting

design as was Britain's Spitfire or the American Corsair.

|

|

The Wildcat was a relatively small aircraft, as

were most of the pre war fighters throughout the world. The aircraft's

narrow gear track is shown to advantage in this ground view of a VMF-121

F4F-3.

|

However, as author Norman Franks wrote, the Allied

crews found that "the Japanese airmen were...far superior to the crude

stereotypes so disparaged by the popular press and cartoonists. And in a

Zero they were highly dangerous."

The hallmark of Japanese fighters had always been

superb maneuverability. Early biplanes — which had been developed

from British and French designs — set the pace. By the mid-1930s,

the Army and Navy had two world-class fighters, the Nakajima Ki.27 and

the Mitsubishi A5M series, respectively, both low-wing, fixed-gear

aircraft. The Ki.27 did have a modern enclosed cockpit, while the A5M's

cockpit was open (except for one variant that experimented with a canopy

which was soon discarded in service.) A major and fatal disadvantage of

most Japanese fighters was their light armament — usually a pair of

.30-caliber machine guns — and lack of armor, as well as their

great flammability.

When the Type "0" first flew in 1939, most Japanese

pilots were enthusiastic about the new fighter. It was fast, had

retractable landing gear and an enclosed cock pit, and carried two 20mm

cannon besides the two machine guns. Initial operational evaluation in

China in 1940 confirmed the aircraft's potential.

By the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor,

the A6M2 was the Imperial Navy's standard carrier fighter, and rapidly

replaced the older A5Ms still in service. As the A6M2 proved successful

in combat, it acquired its wartime nickname, "Zero," although the

Japanese rarely referred to it as such. The evocative name came from the

custom of designating aircraft in reference to the Japanese calendar.

Thus, since 1940 corresponded to the year 2600 in Japan, the fighter was

the Type "00" fighter, which was shortened to "0." The western press

picked up the designation and the name "Zero" was born.

|

|

This

A6M3 is taking off from Rabaul in 1943. Author's Collection

|

|

|

The

Zero's incredible maneuverability came at some expense from its top

speed. In an effort to increase the speed, the designers clipped the

folding wingtips from the carrier-based A6M2 and evolved the land-based

A6M3, Model 32. The pilots were not impressed with the speed increase

and the production run was short, the A6M3 reverting back to its span as

the Model 22. The type was originally called "Hap," after Gen Henry

"Hap" Arnold, Chief of the Army Air Force. Arnold was so angry at the

dubious honor that the name was quickly changed to Hamp. This Hamp is

shown in the Solomons during the

Guadalcanal campaign. Author's Collection

|

The fighter received another name in 1943 which was

almost as popular, especially among the American flight crews. A system

of first names referred to various enemy aircraft, in much the same way

that the postwar NATO system referred to Soviet and Chinese aircraft.

The Zero was tagged "Zeke," and the names were used interchangeably by

everyone, from flight crews to intelligence officers. (Other examples of

the system included "Claude" [A5M], "Betty" [Mitsubishi G4M bomber], and

"Oscar" [Ki.43].)

As discussed in the main text, the Navy and Marine

Corps Wildcats were sometimes initially hard-pressed to defend their

ships and fields against the large forces of Betty bombers and their

Zero escorts, which had ranges of 800 miles or more through the use of

drop tanks.

The Brewster Buffalo had little to show for its few

encounters with the Japanese, which is difficult to understand given the

type's early success during the Russo-Finnish War. The F2A-1, a lighter,

earlier model of the -3 which served with the Marines, was the standard

Finnish fighter plane. In its short combat career in American service,

the Brewster failed miserably.

Thus, the only fighter capable of meeting the

Japanese on anything approaching equal terms was the F4F, which was

fortunate because the Wildcat was really all that was available in those

dark days following Pearl Harbor. Retired Brigadier General Robert E.

Galer described the Wildcat as "very rugged and very mistreated (at

Guadalcanal)." He added:

|

|

Brewster's fat little F2A Buffalo is credited with a

dismal performance in American and British service, although the Finns

racked up a fine score against the Russians. This view of a Marine

Brewster shows the aptness of its popular name, which actually came from

the British. Its characteristic greenhouse canopy and main wheels tucked

snugly into its belly are also well shown. Author's Collection

|

|

|

The

A6M2-N float plane version of the Zero did fairly well, suffering only a

small loss in its legendary maneuverability. Top speed was somewhat

affected, however, and the aircraft's relatively light armament was a

detriment. Photo courtesy of Robert Mikesh

|

Full throttle, very few replacement parts, muddy

landing strips, battle damage, roughly repaired. We loved them. We did

not worry about flight characteristics except when senior officers

wanted to make them bombers as well as fighters.

The Japanese also operated a unique form of fighter.

Other combatants had tried to make seaplanes of existing designs. The

U.S. Navy had even hung floats on the Wildcat, which quickly became the

"Wildcatfish." The British had done it with the Spitfire. But the

resulting combination left much to be desired and sapped the original

design of much of its speed and maneuverability.

The Japanese, however, seeing the need for a

water-based fighter in the expanses of the Pacific, modified the A6M2

Zero, and came up with what was arguably the most successful water-based

fighter of the war, the A6M2-N, which was allocated the Allied codename

"Rufe."

|

|

A

good view of an early F4U-1 under construction in 1942. The massive

amount of wiring and piping for the aircraft's huge Pratt & Whitney

engine shows up here, as do the Corsair's gull wings. Author's

Collection

|

Manufactured by Mitsubishi's competitor, Nakajima,

float-Zeros served in such disparate climates as the Aleutians and the

Solomons. Although the floats bled off at least 40 mph from the

land-based version's top speed, they seemed to have had only a minor

effect on its original maneuverability; the Rule acquired the same

respect as its sire.

While the F4F and P-40 (along with the luckless P-39)

held the line in the Pacific, other, newer designs were leaving

production lines, and none too soon. The two best newcomers were the

Army's Lockheed P-38 Lightning and the Navy's Vought F4U Corsair. The

P-38 quickly captured the headlines and public interest with its unique

twin-boomed, twin-engine layout. It soon developed into a long-range

escort, and served in the Pacific as well as Europe.

|

|

The

Marine pilot of this F4U-1, Lt Donald Balch, contemplates his good

fortune by the damaged tail of his fighter. The Corsair was a relatively

tough aircraft, but like any plane, damage to vital portions of its

controls or powerplant could prove fatal. Author's Collection

|

The Corsair was originally intended to fly from air

craft carriers, but its high landing speed, long nose that obliterated

the pilot's view forward during the landing approach, and its tendency

to bounce, banished the big fighter from American flight decks for a

while. The British, however, modified the aircraft, mainly by clip ping

its wings, and flew it from their small decks.

Deprived of its new carrier fighter — having

settled on the new Grumman F6F Hellcat as its main carrier fighter

— the Navy offered the F4U to the Marines. They took the first

squadrons to the Solomons, and after a few disappointing first missions,

they made the gull-winged fighter their own, eventually even flying it

from the small decks of Navy escort carriers in the later stages of the

war.

|

|

This

"bird-cage" Corsair is landing at Espiritu Santo in September 1943. The

aircraft's paint is well-weathered and its main gear tires are "dusty"

from the coral runways of the area. National Archives 80G-54284

|

|

|

1stLt Rolland N. Rinabarger of VMF-214 in his early

F4U-1 Corsair at Espiritu Santo in September 1943. Badly shot up by

Zeros during an early mission to Kahili only two weeks after this photo

was taken, Lt Rinabarger returned to the States for lengthy treatment.

He was still in California when the war ended. The national insignia on

his Corsair is outlined in red, a short-lived attempt to regain that

color from the prewar marking after the red circle was deleted following

Pearl Harbor to avoid confusion with the Japanese "meatball." Even this

small amount of red was deceptive, however, and by mid-1944, it was gone

from the insignia again. Note the large mud spray on the aft under

fuselage. National Archives 80G-54279

|

Besides the two main fighters, the Army's Oscar and

the Navy's Zeke and its floatplane derivative, the Rufe, the Japanese

flew a wide assortment of aircraft, including land-based bombers, such

as the Mitsubishi G4M (codenamed Betty) and Ki.21 (Sally). Carrier-based

bombers included the Aichi D3A divebomber (the Val) which saw

considerable service during the first three years of the war, and its

stablemate, the torpedo bomber from Nakajima, the B5N (Kate), one of the

most capable torpedo-carriers of the first half of the war. The Marine

Corps squadrons in the Solomons regularly encountered these aircraft.

First Lieutenant James Swett's two engagements on 7 April 1943 netted

the young Wildcat pilot seven Vals, and the Medal of Honor.

Although early wartime propaganda ridiculed Japanese

aircraft and their pilots, returning Allied aviators told different

stories, although the details of their experiences were kept classified.

Each side's culture provided the basis for their aircraft design

philosophies. Eventually, the Japanese were overwhelmed by American

technology and numerical superiority. However, for the important first

18 months of the Pacific war, they had the best. But, as was also the

case in the European theaters, a series of misfortunes, coincidences, a

lack of understanding by leaders, as well as the drain of prolonged

combat, finally allowed the Americans and their Allies to overcome the

enemy's initial edge.

|

|

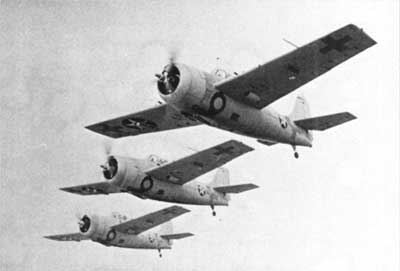

Mitsubishi G4M Betty bombers, perhaps during the

Solomons campaign. Probably the best Japanese land-based bomber in the

war's first two years, the G4M series enjoyed a long range, but could

burst into flames under attack, much to the chagrin of its crews. The

type flew as a suicide aircraft, and finally, painted white with green

crosses, carried surrender teams to various sites. Photo courtesy Robert

Mikesh

|

|

Galer would also be shot down three more times during

his flying career — twice more during World War II and once during

a tour in Korea.

The last half of September 1942 was a time of extreme

trial for the Cactus Air Force (Cactus was the codename for

Guadalcanal). Some relief for the Marine squadrons came in the form of

bad weather and the arrival of disjointed contingents of Navy aircraft

and crews who were displaced from carriers which were either sunk, or

damaged. Saratoga (CV3) and Enterprise (CV6) had been

torpedoed or bombed and sent back to rear area repair stations. The

remaining carriers, Hornet (CV8) and Wasp (CV7), patrolled

off Guadalcanal, their captains and admirals decidedly uneasy about

exposing the last American flattops in the Pacific as meaty targets to

the numerically superior Japanese ships and aircraft.

Wasp took a lurking Japanese submarine's

torpedoes on 15 September while covering a convoy. Now only

Hornet remained. Navy planes and crews from Enterprise,

Saratoga, and now Wasp flew into Henderson Field to

supplement the hard-pressed Marine fighter and bomber squadrons there.

It was still a meager force of 63 barely operational aircraft, a

collection of Navy and Marine F4Fs and SBDs, Navy Grumann TBF Avenger

torpedo bombers, and a few forlorn Army P-400s. A few new Marine pilots

from VMF-121 filtered in on 25 September. However, two days later, the

crews from Enterprise's contingent took their planes out to meet

their carrier steaming in to arrive on station off Guadalcanal. As the

weather broke on the 27th, the Enterprise crews took their leave

of Guadalcanal.

The next day, the Japanese mounted their first raid

in nearly two weeks. Warned by the coastwatchers, Navy and Marine

fighters rose to intercept the 70-plane force. Now a lieutenant colonel,

Harold "Indian Joe" Bauer was making one of his periodic visits from

Efate, and scored a kill, a Zero, before landing.

A native of North Platte, Nebraska, Bauer was

part-Indian (as was Major Gregory "Pappy" Boyington). A veteran of 10

years as a Marine aviator, he watched the progress of the campaign at

Guadalcanal from his rear-area base on Efate. He would come north, using

as an excuse the need to check on those members of his squadron who had

been sent to Henderson and would occasionally fly with the Cactus

fighters.

His victory on the 28th was his first, and soon,

Bauer was a familiar face to the Henderson crews. Bauer was visiting

VMF-224 on 3 October when a coastwatcher reported a large group of

Japanese bombers in bound for Henderson. VMF-223 and -224 took off to

intercept the raiders. The Marine Wildcats accounted for 11 enemy

aircraft; Lieutenant Colonel Bauer claimed four, making him an ace.

On 30 September, Admiral Chester Nimitz,

Commander-in-Chief, Pacific, braved a heavy rain storm to fly in to

Henderson for an awards ceremony. John Smith, Marion Carl, and Bob

Galer, as well as some 1st Marine Division personnel, received the Navy

Cross. Other members of the Cactus Air Force, Navy and Marine, were

decorated with Distinguished Flying Crosses. Nimitz departed in a

blinding rain after presenting a total of 27 medals to the men of the

Cactus Air Force.

|