| Marines in World War II |

|

SILK CHUTES AND HARD FIGHTING: US. Marine Corps Parachute Units in World War II by Lieutenant Colonel Jon T. Hoffman (USMCR) Rendezvous at Gavutu After four months of war, the 1st Marine Division was alerted to its first prospect of action. The vital Samoan Islands appeared to be next on the Japanese invasion list and the Navy called upon the Marines to provide the necessary reinforcements for the meager garrison. In March 1942, Headquarters created two brigades for the mission, cutting a regiment and a slice of supporting forces from each of the two Marine divisions. The 7th Marines got the nod at New River and became the nucleus of the 3d Brigade. That force initially included Edson's 1st Raider Battalion, but no paratroopers. In the long run that was a plus for the 1st Parachute Battalion, which remained relatively untouched as the brigade siphoned off much of the best manpower and equipment of the division to bring itself to full readiness. The division already was reeling from the difficult process of wartime expansion. In the past few months it had absorbed thousands of newly minted Marines, subdivided units to create new ones, given up some of its best assets to field the raiders and parachutists, and built up a base and training areas from the pine forests of New River, North Carolina. The parachutists and the remainder of the division did not have long to wait for their own call to arms, however. In early April, Headquarters alerted the 1st Marine Division that it would begin movement overseas in May. The destination was New Zealand, where everyone assumed the division would have months to complete the process of turning raw manpower into well-trained units. Part of the division shoved off from Norfolk in May. Some elements, including Companies B and C of the parachutists, took trains to the West Coast and boarded naval transports there on 19 June. The rest of the 1st Parachute Battalion was part of a later Norfolk echelon, which set sail for New Zealand on 10 June.

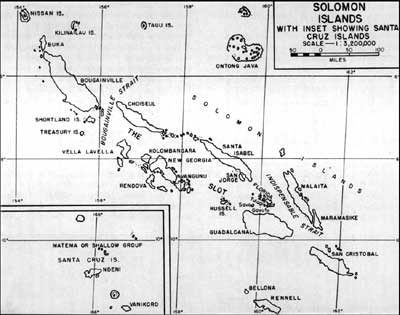

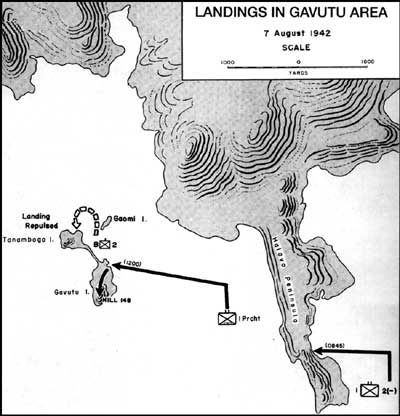

While the parachutists were still at sea, the advance echelon of the division had already bedded down in New Zealand. But the 1st Marine Division's commander, Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift, received a rude shock shortly after he and his staff settled into their headquarters at a Wellington hotel. He and his outfit were slated to invade and seize islands in the southern Solomons group on 1 August, just five weeks hence. To complicate matters, there was very little solid intelligence about the objectives. There were no maps on hand, so the division had to create its own from poor aerial photos and sketches hand-drawn by former planters and traders familiar with the area. Planners estimated that there were about 5,275 enemy on Guadalcanal (home to a Japanese air field under construction) and a total of 1,850 on Tulagi and Gavutu-Tanambogo. Tulagi, 17 miles north of Guadalcanal, was valuable for its anchorage and seaplane base. The islets of Gavutu and Tanambogo, joined by a causeway, hosted a sea plane base and Japanese shore installations and menaced the approaches to Tulagi. In reality, there were probably 536 men on Gavutu Tanambogo, most of them part of construction or aviation support units, though there was at least one platoon of the 3d Kure Special Naval Landing Force, the ground combat arm of the Imperial Navy. The list of heavy weapons on Gavutu Tanambogo included two three-inch guns and an assortment of antiaircraft and antitank guns and machine guns. By the time the last transports docked in New Zealand on 11 July, planners had outlined the operation and the execution date bad slipped to 7 August to allow the division a chance to gather its far-flung echelons and combat load transports. Five battalions of the 1st and 5th Marines would land on the large island of Guadalcanal at 0800 on 7 August and seize the unfinished airfield on the north coast. The 1st Raider Battalion, slated to meet the division on the way to the objective, would simultaneously assault Tulagi. The 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, would follow in trace and support the raiders. The 2d Marines, also scheduled to rendezvous with the division at sea, would serve as the reserve force and land 20 minutes prior to H-Hour on Florida Island, thought to be undefended. The parachutists received the mission of attacking Gavutu at H plus four hours. The delay resulted from the need for planes, ships, and landing craft to concentrate first in support of the Tulagi operation. Once the paratroopers secured Gavutu, they would move on to its sister. The Tulagi, Gavutu-Tanambogo, and Florida operations fell under the immediate control of a task force designated as the Northern Group, headed by Brigadier General William H. Rupertus, the assistant division commander.

After a feverish week of unloading, sorting, and reloading equipment and supplies, the parachutists boarded the transport USS Heywood on 18 July and sailed in convoy to Koro Island in the Fijis, where the entire invasion force conducted landing rehearsals on 28 and 30 July. These went poorly, since the Navy boat crews and most of the 1st Marine Division were too green. The parachute battalion was better trained than most of the division, but this was its very first experience as a unit in conducting a seaborne landing. There is no indication that planners gave any thought to using their airborne capability, though in all likelihood that was due to the lack of transport aircraft or the inability of available planes to make a round-trip flight from New Zealand to the Solomons. The parachutists had the toughest mission in many respects. With a grand total of eight small infantry platoons, they had just 361 Marines, much less than half the manpower of other line battalions. More important, they lacked the punch of heavy mortars and machine guns and had fewer of the light versions of these weapons, too. Even their high proportion of individual automatic weapons would not help much; many of these were the unreliable Reising submachine gun. The late hour of their attack also sacrificed any element of surprise, though planners assumed that naval and aerial firepower would suppress Japanese defenders. Nor was terrain in their favor. The coral reef surrounding the islets meant that the only suitable landing site was the boat basin on the northeast coast of Gavutu, but that point was subject to flanking fire from defenders on Tanambogo. In addition, a steep coral hill dominated the flat coastal area of each islet. Finally, despite a rule of thumb that the attackers should outnumber defenders by three to one in an amphibious assault, they were going up against a significantly larger enemy force. The parachutists' only advantage was their high level of training and esprit. The U.S. task force sailed into the waters between Guadalcanal and Florida Island in the pre-dawn darkness of 7 August 1942. Planes and ships soon opened up on the initial objectives while Marines clambered down cargo nets into landing craft. The parachutists watched while their fellow sea-soldiers conducted the first American amphibious assault of the war. As the morning progressed and opposition on Tulagi appeared light, the antiaircraft cruiser San Juan conducted three fire missions against Gavutu and Tanambogo, expending 1,200 rounds in all. Just prior to noon, the supporting naval forces turned their full fury on the parachute battalion's initial objective. San Juan poured 280 five-inch shells onto Gavutu in four minutes, then a flight of dive bombers from the carrier Wasp struck the northern side of the island, which had been masked from the fire of ship's guns. Oily black smoke rose into the sky and most Marines assumed that few could survive such a pounding, but the display of firepower probably produced few casualties among the defenders, who had long since sought shelter in numerous caves and dugouts.

The bombardment did destroy one three-inch gun on Gavutu as well as the seaplane ramp the parachutists had hoped to land on, thus forcing the Higgins boats to divert to a nearby pier or a small beach. The intense preparation fires had momentarily stunned the defenders, however, and the first wave of Marines, from Company A, clambered from their landing craft onto the dock against little opposition. The Japanese quickly recovered and soon opened up with heavier fire that stopped Company A's advance toward Hill 148 after the Marines had progressed just 75 yards. Enemy gunners also devoted some of their attention to the two succeeding waves and inflicted casualties as they made the long approach around Gavutu to reach the northern shore. Company B landed four minutes after H-Hour against stiff opposition, as did Company C seven minutes later. The latter unit's commander, Captain Richard J. Huerth, took a bullet in the head just as he rose from his boat and he fell back into it dead. Captain Emerson E. Mason, the battalion intelligence officer, also received a fatal wound as he reached the beach. When Company C's two platoons came ashore, they took up positions facing Tanambogo to return enfilading fire from that direction, while Company B began a movement to the left around the hill. That masked them from Tanambogo and allowed them to make some progress. The nature of the enemy action — defenders shooting from concealed underground positions — surprised the parachutists. Several Marines became casualties when they investigated quiet cave openings, only to be met by bursts of fire. The battalion communications officer died in this manner. Many other parachutists withheld their fire because they saw no targets. Marines tossed grenades into caves and dugouts, but oftentimes soon found themselves being fired on from these "silenced" positions. (Later investigation revealed that baffles built inside the entrances protected the occupants or that connecting trenches and tunnels allowed new defenders to occupy the defensive works.)

Twenty minutes into the battle, Major Williams began leading men up Hill 148 and took a bullet in his side that put him out of action. Enemy fire drove off attempts to pull him to safety and his executive officer, Major Charles A. Miller, took control of the operation. Miller established the command post and aid station in a partially demolished building near the dock area. Around 1400 he called for an air strike against Tanambogo and half an hour later he radioed for reinforcements.

While the parachutists awaited this assistance, Company B and a few men from Company A continued to attack Hill 148 from its eastern flank. Individuals and small groups worked from dugout to dugout under rifle and machine gun fire from the enemy. Learning from initial experience, Marines began to tie demolition charges of TNT to long boards and stuff them into the entrances. That prevented the enemy from throwing back the explosives and it permanently put the positions out of action. Captain Harry L. Torgerson and Corporal Johnnie Blackan distinguished themselves in this effort. Other men, such as Sergeant Max Koplow and Corporal Ralph W. Fordyce, took a more direct approach and entered the bunkers with submachine guns blazing. Platoon Sergeant Harry M. Tully used his marksmanship skill and Johnson rifle to pick off a number of Japanese snipers. The parachutists got their 60mm mortars into action, too, and used them against Japanese positions on the upper slopes of Hill 148. By 1430, the eastern half of the island was secure, but enemy fire from Tanambogo kept the parachutists from overrunning the western side of the bill. In the course of the afternoon, the Navy responded to Miller's call for support. Dive bombers worked over Tanambogo, then two destroyers closed on the island and thoroughly shelled it. In the midst of this action, one pilot mistakenly dropped his ordnance on Gavutu's hilltop and inflicted several casualties on Company B. By 1800, the battalion succeeded in raising the U.S. flag at the summit of Hill 148 and physically occupying the remainder of Gavutu. With the suppression of fire from Tanambogo and the cover of night, the parachutists collected their casualties, to include Major Williams, and began evacuating the wounded to the transports.

Ground reinforcements arrived more slowly than fire support. Company B, 1st Battalion, 2d Marines, reported to Miller on Gavutu at 1800. He ordered them to make an amphibious landing on Tanambogo and arranged for preparatory fire by a destroyer. The parachutists also would support the move with their fire and Company C would attack across the causeway after the landing. Miller, perhaps buoyed by the late afternoon decrease in enemy fire from Tanambogo, was certain that the fresh force would carry the day. For his part, the Company B commander left the meeting under the impression that there were only a few snipers left on the island. The attack ran into trouble from the beginning and the Marine force ended up withdrawing under heavy fire. During the night, the parachutists dealt with Japanese emerging from dugouts or swimming ashore from Tanambogo or Florida. A heavy rain helped conceal these attempts at infiltration, but the enemy accomplished little. At 2200, General Rupertus requested additional forces to seize Tanambogo and the 3d Battalion, 2d Marines, went ashore on Gavutu late in the morning on 8 August. They took over many of the positions facing Tanambogo and in the afternoon launched an amphibious attack of one company supported by three tanks. Another platoon followed up the landing by attacking across the causeway. Bitter fighting ensued and the 3d Battalion did not completely secure Tanambogo until 9 August. This outfit suffered additional casualties on 8 August when yet another Navy dive bomber mistook Gavutu for Tanambogo and struck Hill 148.

In the first combat operation of an American parachute unit, the battalion had suffered severe losses: 28 killed and about 50 wounded, nearly all of the latter requiring evacuation. The dead included four officers and 11 NCOs. The casualty rate of just over 20 percent was by far the highest of any unit in the fighting to secure the initial lodgement in the Guadalcanal area. (The raiders were next in line with roughly 10 percent.) The Japanese force defending Gavutu-Tanambogo was nearly wiped out, with only a handful surrendering or escaping to Florida Island. Despite the heavy odds the parachutists had faced, they had proved more than equal to the faith placed in their capabilities and had distinguished themselves in a very tough fight. In addition to raw courage, they had displayed the initiative and resourcefulness required to deal with a determined and cunning enemy. On the night of 8 August, a Japanese surface force arrived from Rabaul and surprised the Allied naval forces guarding the transports. In a brief engagement the enemy sank four cruisers and a destroyer, damaged other ships, and killed 1,200 sailors, all at minimal cost to themselves. The American naval commander had little choice the next morning but to order the early withdrawal of his force. Most of the transports would depart that afternoon with their cargo holds half full, leaving the Marines short of food, ammunition, and equipment. The parachutists suffered an additional loss that would make life even more miserable for them. They had landed on 7 August with just their weapons, ammunition, and a two-day supply of C and D rations. They had placed their extra clothing, mess gear, and other essential field items into individual rolls and loaded them on a landing craft for movement to the beach after they secured the islands. As the parachutists fought on shore, Navy personnel decided they needed to clear out the boat, so they uncomprehendingly tossed all the gear into the sea. The battalion ended its brief association with Gavutu on the afternoon of 9 August and shifted to a bivouac site on Tulagi. The parachutists had the toughest mission in many respects. With a grand total of eight small infantry platoons, they had just 361 Marines, much less than half the manpower of other line battalions. More important, they lacked the punch of heavy mortars and machine guns and had fewer of the light versions of these weapons, too. Even their high proportion of individual automatic weapons would not help much; many of these were the unreliable Reising submachine gun. The late hour of their attack also sacrificed any element of surprise, though planners assumed that naval and aerial firepower would suppress Japanese defenders. Nor was terrain in their favor. The coral reef surrounding the islets meant that the only suitable landing site was the boat basin on the northeast coast of Gavutu, but that point was subject to flanking fire from defenders on Tanambogo. In addition, a steep coral hill dominated the flat coastal area of each islet. Finally, despite a rule of thumb that the attackers should outnumber defenders by three to one in an amphibious assault, they were going up against a significantly larger enemy force. The parachutists' only advantage was their high level of training and esprit. The U.S. task force sailed into the waters between Guadalcanal and Florida Island in the pre-dawn darkness of 7 August 1942. Planes and ships soon opened up on the initial objectives while Marines clambered down cargo nets into landing craft. The parachutists watched while their fellow sea-soldiers conducted the first American amphibious assault of the war. As the morning progressed and opposition on Tulagi appeared light, the antiaircraft cruiser San Juan conducted three fire missions against Gavutu and Tanambogo, expending 1,200 rounds in all. Just prior to noon, the supporting naval forces turned their full fury on the parachute battalion's initial objective. San Juan poured 280 five-inch shells onto Gavutu in four minutes, then a flight of dive bombers from the carrier Wasp struck the northern side of the island, which had been masked from the fire of ship's guns. Oily black smoke rose into the sky and most Marines assumed that few could survive such a pounding, but the display of firepower probably produced few casualties among the defenders, who had long since sought shelter in numerous caves and dugouts.

The bombardment did destroy one three-inch gun on Gavutu as well as the seaplane ramp the parachutists had hoped to land on, thus forcing the Higgins boats to divert to a nearby pier or a small beach. The intense preparation fires had momentarily stunned the defenders, however, and the first wave of Marines, from Company A, clambered from their landing craft onto the dock against little opposition. The Japanese quickly recovered and soon opened up with heavier fire that stopped Company A's advance toward Hill 148 after the Marines had progressed just 75 yards. Enemy gunners also devoted some of their attention to the two succeeding waves and inflicted casualties as they made the long approach around Gavutu to reach the northern shore. Company B landed four minutes after H-Hour against stiff opposition, as did Company C seven minutes later. The latter unit's commander, Captain Richard J. Huerth, took a bullet in the head just as he rose from his boat and he fell back into it dead. Captain Emerson E. Mason, the battalion intelligence officer, also received a fatal wound as he reached the beach. When Company C's two platoons came ashore, they took up positions facing Tanambogo to return enfilading fire from that direction, while Company B began a movement to the left around the hill. That masked them from Tanambogo and allowed them to make some progress. The nature of the enemy action — defenders shooting from concealed underground positions — surprised the parachutists. Several Marines became casualties when they investigated quiet cave openings, only to be met by bursts of fire. The battalion communications officer died in this manner. Many other parachutists withheld their fire because they saw no targets. Marines tossed grenades into caves and dugouts, but oftentimes soon found themselves being fired on from these "silenced" positions. (Later investigation revealed that baffles built inside the entrances protected the occupants or that connecting trenches and tunnels allowed new defenders to occupy the defensive works.)

Twenty minutes into the battle, Major Williams began leading men up Hill 148 and took a bullet in his side that put him out of action. Enemy fire drove off attempts to pull him to safety and his executive officer, Major Charles A. Miller, took control of the operation. Miller established the command post and aid station in a partially demolished building near the dock area. Around 1400 he called for an air strike against Tanambogo and half an hour later he radioed for reinforcements.

While the parachutists awaited this assistance, Company B and a few men from Company A continued to attack Hill 148 from its eastern flank. Individuals and small groups worked from dugout to dugout under rifle and machine gun fire from the enemy. Learning from initial experience, Marines began to tie demolition charges of TNT to long boards and stuff them into the entrances. That prevented the enemy from throwing back the explosives and it permanently put the positions out of action. Captain Harry L. Torgerson and Corporal Johnnie Blackan distinguished themselves in this effort. Other men, such as Sergeant Max Koplow and Corporal Ralph W. Fordyce, took a more direct approach and entered the bunkers with submachine guns blazing. Platoon Sergeant Harry M. Tully used his marksmanship skill and Johnson rifle to pick off a number of Japanese snipers. The parachutists got their 60mm mortars into action, too, and used them against Japanese positions on the upper slopes of Hill 148. By 1430, the eastern half of the island was secure, but enemy fire from Tanambogo kept the parachutists from overrunning the western side of the bill. In the course of the afternoon, the Navy responded to Miller's call for support. Dive bombers worked over Tanambogo, then two destroyers closed on the island and thoroughly shelled it. In the midst of this action, one pilot mistakenly dropped his ordnance on Gavutu's hilltop and inflicted several casualties on Company B. By 1800, the battalion succeeded in raising the U.S. flag at the summit of Hill 148 and physically occupying the remainder of Gavutu. With the suppression of fire from Tanambogo and the cover of night, the parachutists collected their casualties, to include Major Williams, and began evacuating the wounded to the transports.

Ground reinforcements arrived more slowly than fire support. Company B, 1st Battalion, 2d Marines, reported to Miller on Gavutu at 1800. He ordered them to make an amphibious landing on Tanambogo and arranged for preparatory fire by a destroyer. The parachutists also would support the move with their fire and Company C would attack across the causeway after the landing. Miller, perhaps buoyed by the late afternoon decrease in enemy fire from Tanambogo, was certain that the fresh force would carry the day. For his part, the Company B commander left the meeting under the impression that there were only a few snipers left on the island. The attack ran into trouble from the beginning and the Marine force ended up withdrawing under heavy fire. During the night, the parachutists dealt with Japanese emerging from dugouts or swimming ashore from Tanambogo or Florida. A heavy rain helped conceal these attempts at infiltration, but the enemy accomplished little. At 2200, General Rupertus requested additional forces to seize Tanambogo and the 3d Battalion, 2d Marines, went ashore on Gavutu late in the morning on 8 August. They took over many of the positions facing Tanambogo and in the afternoon launched an amphibious attack of one company supported by three tanks. Another platoon followed up the landing by attacking across the causeway. Bitter fighting ensued and the 3d Battalion did not completely secure Tanambogo until 9 August. This outfit suffered additional casualties on 8 August when yet another Navy dive bomber mistook Gavutu for Tanambogo and struck Hill 148.

In the first combat operation of an American parachute unit, the battalion had suffered severe losses: 28 killed and about 50 wounded, nearly all of the latter requiring evacuation. The dead included four officers and 11 NCOs. The casualty rate of just over 20 percent was by far the highest of any unit in the fighting to secure the initial lodgement in the Guadalcanal area. (The raiders were next in line with roughly 10 percent.) The Japanese force defending Gavutu-Tanambogo was nearly wiped out, with only a handful surrendering or escaping to Florida Island. Despite the heavy odds the parachutists had faced, they had proved more than equal to the faith placed in their capabilities and had distinguished themselves in a very tough fight. In addition to raw courage, they had displayed the initiative and resourcefulness required to deal with a determined and cunning enemy. On the night of 8 August, a Japanese surface force arrived from Rabaul and surprised the Allied naval forces guarding the transports. In a brief engagement the enemy sank four cruisers and a destroyer, damaged other ships, and killed 1,200 sailors, all at minimal cost to themselves. The American naval commander had little choice the next morning but to order the early withdrawal of his force. Most of the transports would depart that afternoon with their cargo holds half full, leaving the Marines short of food, ammunition, and equipment. The parachutists suffered an additional loss that would make life even more miserable for them. They had landed on 7 August with just their weapons, ammunition, and a two-day supply of C and D rations. They had placed their extra clothing, mess gear, and other essential field items into individual rolls and loaded them on a landing craft for movement to the beach after they secured the islands. As the parachutists fought on shore, Navy personnel decided they needed to clear out the boat, so they uncomprehendingly tossed all the gear into the sea. The battalion ended its brief association with Gavutu on the afternoon of 9 August and shifted to a bivouac site on Tulagi.

|