| Marines in World War II |

|

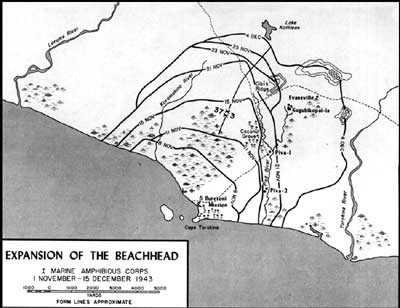

SILK CHUTES AND HARD FIGHTING: US. Marine Corps Parachute Units in World War II by Lieutenant Colonel Jon T. Hoffman (USMCR) Bougainville On 1 November 1943, the 3d and 9th Marines, assisted by the 2d Raider Battalion, seized a swath of Bougainville's coast from Cape Torokina to the northwest. At the same time, elements of the 3d Raider Battalion assaulted Puruata Island just off the cape. The single Japanese company and one 75mm gun defending the area gave a good account of themselves until overwhelmed by the invasion force. Over the next several days the Marines advanced inland to extend their perimeter. There were occasional engagements with small enemy patrols, but the greatest resistance during this period came from the terrain, which consisted largely of swampland and dense jungle beginning just behind the beach. The thing most Marines remembered about Bougainville was the deep, sucking mud that seemed to cover everything not already underwater. Japanese resistance stiffened as they moved troops to the area on foot and by barge. The Marines fought several tough battles in mid November and suffered significant casualties trying to move forward through the thick vegetation, which concealed Japanese defensive positions until the Marines were just a few feet away. Heavy rains and the ever-present mud made logistics a nightmare and quickly exhausted the troops. Nevertheless, the perimeter continued to expand as I MAC sought an area large enough to protect the future airfields from enemy interference. By 20 November, I MAC had all of the 3d Marine Division and the 37th Infantry Division, plus the 2d Raider Regiment, on the island. In accordance with the original plan, corps headquarters arranged for the parachute regiment to come forward in echelon from Vella Lavella and assume its role as the reserve force. The 1st Parachute Battalion embarked on hoard ships on 22 November and arrived at Bougainville the next day, where it joined the raider regiment in reserve.

The corps planners wanted to make aggressive use of the reserve force. In addition to assigning it the normal roles of reinforcing or counterattacking, I MAC ordered its reserve to be prepared "to engage in land or water-borne raider type operations." By 26 November, the corps had established a defensible beachhead and enemy activity was at a low ebb. However, the Japanese 23d Infantry Regiment occupied high ground to the northeast of the U.S. perimeter and remained a threat. Enemy medium artillery also periodically shelled rear areas. To prevent the Japanese from gathering strength with impunity, I MAC decided to establish a force in the enemy rear from whence it could "conduct raids along coast and inland to main east-west trail; destroy Japs, installations, supplies, with particular attention to disrupting Jap communications and artillery." The plan called for Major Richard Fagan's 1st Parachute Battalion, Company M of the raiders, and artillery forward observers to land 10 miles to the east, neart of Koiari, prior to dawn on 28 November. The raiders would secure the patrol base while the parachutists conducted offensive operations. They would remain there until corps ordered them to withdraw. A Japanese air attack and problems with the boat pool delayed the operation for 24 hours. Just after midnight on 28 November, the 739 men of the reinforced battalion embarked on landing craft near Cape Torokina and headed down the coast. The main body of the parachute battalion went ashore at their assigned objective, but Company M and the parachute headquarters company landed nearly 1,000 yards farther to the east. Much to the surprise of the first parachutists coming off the boats, a Japanese officer walked onto the beach and attempted to engage them in conversation. That bizarre incident made some sense when the Marines discovered that they had landed in the midst of a large enemy supply dump. The Japanese leader must have thought that these were his own craft delivering or picking up supplies. In any case, the equally surprised enemy initially put up little opposition to the Marine incursion. Major Fagan, located with the main body, was concerned about the separation of his unit and felt that the Japanese force in the vicinity of the dump was probably much bigger than his own. Given those factors, he quickly established a tight perimeter defense about 350 yards in width and just 180 yards inland.

By daylight, the Japanese had recovered from their shock and begun to respond aggressively to the threat in their rear area. They brought to bear continuous fire from 90mm mortars, knee-mortars, machine guns, and rifles; the volume of fire increased as the day wore on. Periodically infantry rushed the Marine lines. The picture improved somewhat by 0930 when the body of raiders and headquarters personnel moved down the beach and fought their way into the battalion perimeter. The battalion's radio set malfunctioned about this time, however, and Fagan could not receive messages from I MAC. For the moment he could still send them, but was unsure if the corps headquarters heard them. The artillery spotters could talk to the batteries, though, and they fed a steady diet of 155mm shells to the Japanese. Unbeknownst to Fagan, the raider company had its own radio and maintained independent contact with the corps. These communication snafus would lead to great confusion. By late morning, I MAC already was thinking in terms of pulling out the beleaguered force. At 1128, it arranged to boat 3d Marine Division half-tracks (mounting 75mm guns) to assist in covering a withdrawal. Staffers also called in planes to provide close air support. Around noon Fagan sent a message requesting evacuation and corps decided to abort the mission. It radioed the battalion at 1318 with information concerning the planned withdrawal, but the parachutists did not get the word. As a consequence, Fagan sent more messages asking for boats and a resupply of ammunition, which was running low. For some reason, neither Fagan nor corps headquarters used the artillery net for messages other than calls for fire support. While sending other traffic would have been a violation of standard procedures, it certainly was justified under the circumstances. (After the operation was over, Fagan would express dismay that Company M radio operators, without his knowledge or approval, had sent their own pleas for boats and ammunition throughout the afternoon.)

At 1600, the landing craft arrived off the beach and made a run in to pick up the raid force. The Japanese focused their mortar fire on the boats and the sailors backed off. They tried again almost immediately, but again drew back due to the intense bombardment from the beach. Things looked bleak as the onset of night reduced visibility to zero in the dense jungle and increased the likelihood of a strong enemy counterattack. Ammunition stocks were dwindling rapidly and weapons failed due to heavy firing and the accumulation of gritty sand. Marines resorted to employing Japanese weapons, to include a small field piece. The destroyers Fullam, Lansdowne, and Lardner and two LCI gunboats came on the scene after 1800 and turned the tide. The heavy fires at short range of the Lansdowne and the LCIs soon silenced most of the Japanese mortars and boats were able to reach the shore unmolested about 1920. American artillery also continued to rain down around the perimeter. The parachutists and raiders exhibited a cool discipline, slowly collapsing their perimeter into the beach and conducting an orderly backload. After a thorough search to ensure that no one remained behind, the final few Marines stepped onto the last wave of landing craft and pulled out to sea at 2100. The raid might he counted a failure since it did not go according to plan, but it did achieve some positive things. The day of fighting in the midst of the enemy supply dump destroyed considerable stocks of ammunition, food, and medical supplies. Rough estimates placed Japanese casualties at nearly 300 dead and wounded, though there was no way to confirm whether this figure was high or low. Undoubtedly the aggressive operation behind the lines caused the enemy to worry that the Americans might repeat the tactic elsewhere with better luck. The Marine force attained these ends at considerable cost. Total casualties were 17 dead, 7 missing, and 97 wounded (two-thirds of them requiring evacuation). In one day of fighting the parachute battalion lost nearly 20 percent of its strength, as well as many weapons and individual items of equipment. The unit was not shaken, hut it was severely bruised. While the 1st Battalion prepared for its trial by fire at Koiari, the rest of the regiment temporarily enjoyed a morale-boosting turkey dinner on Thanksgiving Day. (Many of the parachutists awoke that night with a severe case of diarrhea, probably induced by some part of the meal that had gone had.) On 3 December, the regimental headquarters, the weapons company, and the 3d Battalion embarked on five LCIs and joined a small convoy headed for Bougainville. The regiment received its first taste of action that evening when Japanese aircraft attacked at sundown. Accompanying destroyers downed three of the interlopers in a short but hot fight and the ships sailed on unharmed. The convoy deposited the parachutists in the Empress Augusta Bay perimeter the next day and they went into bivouac adjacent to the 1st Battalion. They did not have to wait long for their next fight.

Early December reconnaissance by the 3d Marine Division indicated that the Japanese were not occupying the high ground on the west side of the Torokina River, just to the east of the perimeter. The division commander decided to expand his holdings to include this key terrain, hut the difficulty of supplying large forces in forward areas deterred him from immediately moving his entire line forward. His solution was the creation of strong outposts to hold the ground until engineers cut the necessary roads. On 5 December, corps attached the parachute regiment (less the 1st and 2d Battalions) to the 3d Division, which ordered this fresh force to occupy and defend Hill 1000, while other elements of the division outposted other high ground nearby. To accomplish the mission, Williams decided to turn his rump regiment into two battalions by creating a provisional force consisting of the weapons company, headquarters personnel, and the 3d Battalion's Company I. The parachutists moved out on foot from their bivouac at 1130 with three days of rations and a unit of fire in their packs. By 1800 they were in a perimeter defense around the peak of Hill 1000, 3d Battalion (less I Company) on the south and the provisional unit to the north. Supply proved to be the first difficulty, as "steep slopes, overgrown trails, and deep mud" hampered the work of carrying parties. Division eventually had to resort to air drops to overcome the problem. While some parachutists labored to bring up food and ammunition, others patrolled the vicinity. Beginning on the 6th, the outpost line began to turn into a linear defense as the division fed more units forward. The small parachute regiment had a hard time trying to cover its 3,000 yards of assigned frontage on top of the sprawling, ravine-pocked, jungle-covered hill mass. On 7 December a 3d Battalion patrol discovered abandoned defensive positions on an eastern spur of Hill 1000. The unit brought back documents showing that a reinforced enemy company had set up the strongpoint on what would become known as Hellzapoppin Ridge. The battalion commander, Major Vance, ordered two platoons of Company K to move forward to straight en the line. With no map and only vague directions as a guide, the unit could not find its objective in the dense jungle and remained out of touch until the next day. That night a small Japanese patrol probed the lines of the regiment and the enemy re-occupied the position on the east spur. On the morning of 8 December, a patrol from the provisional battalion investigated the spur and a Japanese platoon ambushed it. The parachutists returned to friendly lines with one man missing. They reorganized and departed an hour later to search for him and tangled with the enemy in the same spot. This time they suffered eight wounded in a 20-minute firefight and withdrew. Twice during the day the regiment received artillery and mortar fire, which it believed to he friendly in origin. The rounds knocked out the regimental command post's telephone communications and caused five serious casualties in Company K.

In light of the increasing enemy activity, Williams decided to straighten out his lines and establish physical contact between the flanks of the battalions. This required the right flank of Company I and the left flank of Company K to advance. On the morning on 9 December, Major Vance personally led a patrol to reconnoiter the new position. Eight Japanese manning three machine guns ambushed that force and it with drew, leaving behind one man. At 1415, the left half of Company K attacked. Within 20 minutes, strong Japanese rifle and machine gun fire brought it to a halt. Although after-action reports from higher echelons later indicated only that Company I did not move forward, those Marines fought hard that day and suffered casualties attempting to advance. Among others, the executive officer, First Lieutenant Milt Cunha, was killed in action and First Sergeant I. J. Fansler, Jr. had his rifle shot out of his hands.

The inability of Company I to make progress enlarged the dangerous gap in the center of the regiment's line. Vance ordered two demolition squads to refuse K's left flank and Williams sent a platoon of headquarters personnel from the provisional battalion to fill in the remainder of the hole. Snipers infiltrated the Marine line and the regimental commander turned most of his command post group into a reserve force to backstop the rifle companies. The parachutists called in artillery to Company's K's front and Japanese fire finally began to slacken after 1615. The fighting was intense and Company K initially reported casualties of 36 wounded and 12 killed. That figure later proved too high, though exact losses in the attack were hard to ascertain since the parachutists had 18 men missing and took casualties in other actions that day. Major Vance suffered a gunshot wound in the foot and turned over the battalion to Torgerson. The executive officer of the 21st Marines was in the area, apparently reconnoitering prior to his regiment taking over that portion of the front the next day. He responded to a request for assistance and had his Company C haul ammunition up to the parachutists. When those Marines completed that task, he offered to have them bolster the parachute line and Williams accepted. For the rest of the night the parachute regiment fired artillery missions at 15-minute intervals against likely enemy positions. The Japanese responded with occasional small arms fire. Division shifted the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, to a reserve position behind Hill 1000 and placed the parachute regiment under the tactical control of the 9th Marines, scheduled to occupy the line on their left the next day.

That was not the only action for the parachutists on 9 December. That morning the provisional battalion had sent a platoon of Company I reinforced by two weapons company machine gun squads on a patrol to circle the eastern spur and investigate the area between it and the Torokina River. The unit moved out to the north east and reached the rear of Hellzapoppin Ridge, where it came upon two Japanese setting up a machine gun along the trail. The Marine point man observed the activity and alerted the patrol leader, Captain Jack Shedaker, who killed both in quick succession with his carbine. Unbeknownst to the Marines, they were in the midst of a Japanese ambush and the enemy immediately returned fire from positions in a swamp on the left side of the trail. The first burst of fire killed one Marine, but the parachute machine gunners quickly got their weapons in action and opened a heavy return fire into the swamp. While the tail-end Marine squad tried to flank the enemy position, other parachutists moved up onto the higher ground on the right side of the trail to obtain better fields of observation and fire. The Japanese soon withdrew under this withering response, but not without heavy losses since they had to cross open ground in full view of Marines on the slope above them. The patrol estimated that it killed 16 Japanese, though regiment later downgraded the claim to 12. The reinforced platoon retraced its steps to the Marine perimeter, its only loss being the one man killed at the start of the ambush.

At least one other patrol made contact that day and one of its machine gun squads became separated in the melee. A third patrol sent to search for the missing men came up empty handed. Three of the machine gunners made it back to friendly lines the next day, but a lieutenant and three enlisted men remained missing. The enemy continued to harass the parachutists with small arms fire on the morning of 10 December and drove back a patrol sent out to recover Marine dead on Hellzapoppin Ridge. To deal with the problem, Companies K and L with drew 200 yards and called down a 45-minute artillery barrage. When they advanced to reoccupy their positions, they had to fight through Japanese soldiers who had moved closer to the Marine lines to avoid the artillery. Later in the day, the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, relieved the left of the parachute line and the 1st Battalion, 21st Marines, took over the right. Williams dissolved the provisional battalion and the rump regiment remained attached to the 9th Marines as its reserve force. Over the next few days the parachutists ran patrols and began building their portion of the corps reserve line of defense. The reserve mission was not entirely quiet, as the parachutists suffered three casualties in a patrol contact and an air raid. Two machine gunners from the weapons company took matters into their own hands and went forward of the front lines searching for their comrades missing since 9 December. Their unofficial heroics proved fruit less. Meanwhile, the 21st Marines spent the period of 12 to 18 December reducing Hellzapoppin Ridge. Their efforts were successful only after corps supported them with a lavish outlay of aerial firepower (several hundred 100-pound bombs) and the dedicated assistance of a specially sited 155mm artillery battery.

The Army's XIV Corps headquarters relieved I MAC in command of the operation on 15 December and the Americal Division began replacing the 3d Marine Division on 21 December. As part of this shift of forces, the regimental companies and 1st Battalion of the parachutists fell under Colonel Alan Shapley's 2d Raider Regiment, with Williams assuming the billet of executive officer of the combined force. While the 3d Parachute Battalion continued as the reserve force for the 9th Marines, the raider and parachute regiment took over the frontline positions of the 3d Marines on 22 December. This placed them with their right flank on the sea at the eastern end of the Empress Augusta Bay perimeter. Army units relieved the 9th Marines on Christmas Day and the 3d Parachute Battalion departed Bougainville soon thereafter. The 1st Battalion conducted aggressive patrols and made its only serious contact on 28 December. Company A crossed the Torokina River inland and swept down the far bank to the sea. Near the river mouth it encountered a strong Japanese position and quickly reduced 8 pillboxes, killed 18 of the enemy, and drove off another 20 defenders. Three parachutists died and two were wounded. Shapley joined the company to observe the final action and commended it for an "excellent job." The last parachutists left Bougainville in the middle of January 1944 and sailed to Guadalcanal.

|