|

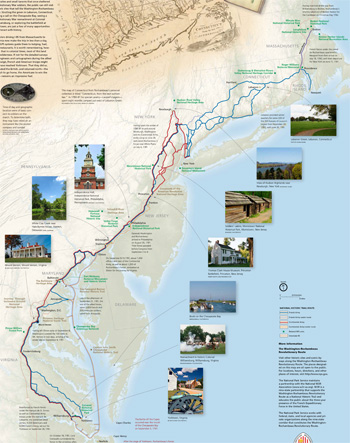

Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail CT-DC-DE-MA-MD-NJ-NY-PA-RI-VA |

|

NPS photo | |

"The essential and direct End of the present defensive alliance is to maintain… the liberty, Sovereignty, and independence...of said united States."

—from the "Treaty of Alliance," 1778, National Archives and Records Administration

France Joins the Cause

When leaders of 13 of the American colonies boldly declared independence from Great Britain in 1776, they knew that without military supplies, naval power, and money their quest would fail. At that time Great Britain possessed the greatest navy and one of the best armies in the world. Well-trained and better-equipped British forces overpowered America’s Continental Army troops from the beginning of the Revolutionary War.

Facing a strong enemy with so few resources forced the Americans to search for allies to aid them in their cause. Beginning in 1775, contacts were underway between the Court of Louis XVI and the patriots. France had deep ties to North America, establishing settlements there long before the French and Indian War of the 1750s. There were, however, other motives for the king’s support of a colonial rebellion on a distant continent—bolstering his nation’s economic and political power worldwide, as well as avenging France’s loss to Great Britain in the Seven Years War.

The American mission was a success. Louis XVI agreed to provide muskets, mortars, gunpowder, and cash to the new nation. In 1778 France signed a “Treaty of Alliance” with the United States of America. Their recognition of the young country as a sovereign power earned the fledgling nation respect throughout the world. French aid helped the Americans, but by March 1780 the war in the colonies was at a stalemate. France responded by sending thousands of its best soldiers across the Atlantic to help George Washington’s patriots hold off the British. Their commander was a man of great experience and respect, General Jean Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau.

"the [American] men were with out uniforms and covered with rags; most of them were barefoot"

—comte de Clermont Crevecceur, commenting on the appearance of the American troops, 1781

The Long March to Independence

The 450 officers and 5,300 men of Rochambeau's Expeditionary Forces landed on the coast of Rhode Island in July 1780. Generals Washington and Rochambeau agreed to wait until the spring of 1781 to launch a joint military offensive, so the French army spent the bitter winter camped in Newport, Rhode Island, and Lebanon, Connecticut. During that time, French officers prepared for the march that would unite them with Continental troops at the Hudson River. From there the allied forces planned to attack British General Clinton's stronghold in New York City, a few days' march to the south.

The first French forces left Newport on June 11, 1781. Moving thousands of men and animals over waterways, through unfamiliar forests, and across hilly terrain was an enormous and risky undertaking. Roads were sometimes impassable. Finally on July 4, 1781, the two armies met in Phillipsburg, New York.

There was, however, a change in plans. On learning that French Admiral de Grasse was steering his warships to the Chesapeake Bay, Washington and Rochambeau decided to abandon the offensive on Clinton and head south. Allied troops departed from Phillipsburg, New York, on August 18 and arrived outside Yorktown, Virginia, on September 28.

Their efforts were worthwhile. The allied victory at Yorktown proved to be a turning point in the war. American colonists, who initially greeted the French with suspicion on the 600-mile trip south from Rhode Island to Virginia in 1781, hailed them as heroes on their return trip north. The trail both armies marched is now preserved as the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route and celebrates the allies' joint labors to achieve American independence.

Officers and Men

The allied forces comprised a diverse group with a common goal. French troops impressed colonists with their professional military training and elegantly decorated uniforms. The Continental Army, however, included able bodies, from boys who were barely teens to men who were grandfathers. Some had been trained; others had never fired a shot. A man's social or political status often determined his rank. Although most American soldiers were of British ancestry, some descended from Germans, Africans, and American Indians. Only one black soldier served under Rochambeau but Baron von Closen, a member of Rochambeau's French army at Yorktown, noted in July 1781, "A quarter of [the American army] are Negroes, merry, confident and sturdy." Many of those African Americans who fought under Washington were freedmen and former slaves who hoped American independence would improve the status of their race.

Moving an Army

From June through September 1781 soldiers on the march to Yorktown carried their own weapons, utensils, and other personal items. A man often hauled 60 pounds or more for up to eight hours a day. Troops of both armies required food, water, and a safe place to rest each night.

A soldier's lodging depended on his military rank. On the way to and from Yorktown French and American officers stayed in nearby homes or taverns, while the men slept outside in tents. A camp of thousands required hours to assemble. French Chaplain Abbe Robin complained of having to wait "until the hottest part of the day for the baggage wagons before we can take any repose. The sun has sometimes finished her course, before our weak stomachs have begun to receive and digest the necessary food."

The troops received meal rations and dug pits where they could set their cooking kettles. Collecting pure water was essential. Robin described being "stretched out full length upon the ground, panting with thirst." The heat plagued the French. American troops did not have elaborate uniforms, but their linen overalls were better suited to summer in the eastern United States than the wool garments worn by most of Rochambeau's men. To avoid marching at the hottest time of day, soldiers were on the road by 4 a.m. and walked 12 to 15 miles to their next campsite by late morning.

Wives and children of the Continental Army and French troops sometimes followed their husbands, brothers, and fathers to camp. These civilians, uprooted by war, sewed, cooked, and washed clothes for the men, often earning a bit of money for their services. They also nursed the wounded. American soldiers benefited by the presence of women in the camps, but Washington noted that these "camp followers" presented a physical and financial burden for the army. Like the enlisted troops, they needed to be fed and sheltered, but did not fight.

"let history huzzah for you."

—George Washington, silencing his cheering troops at the British surrender of Yorktown, 1781

Allied Victory at Yorktown

The 300-mile trek from New York to Virginia took five weeks, during which allied troops endured heatstroke, thirst, and fatigue. The French and Americans separated for part of the route, making road travel easier and effectively deceiving British General Clinton, who was still expecting an allied attack on New York.

The allies received encouraging news that on September 5 French Admiral de Grasse's fleet won the Battle off the Capes against British war ships. De Grasse established a blockade of the Chesapeake Bay, cutting off naval support to the British and allowing Cornwallis and his men no escape route from Yorktown. By September 28, 1781, when French and American forces arrived, Cornwallis was cornered and allied troops immediately opened siege on British fortifications.

French and American artillery first fired on the British on October 9. By October 14 an exhausted French soldier wrote in his diary, "The whole redoubt was so full of dead and wounded that one had to walk on top of them." Days later, with their defenses shattered, the British called for a ceasefire. On October 19, 1781, British troops solemnly walked through two lines of soldiers—Americans on one side, French on the other—and laid down their arms.

The allied victory at Yorktown was the last significant mainland battle of the American Revolution and enabled the 13 colonies to become one nation. The cooperation of Rochambeau's forces under the leadership of Washington, the smart coordination of allied land and naval resources, and the soldiers' perseverance during their long journey made the effort a success. When French troops marched back north to New England in 1782, they were welcomed and thanked by grateful Americans.

Along the Allied Route Today

Discovering a Revolutionary War Trail

The Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route comprises a network of roads and waterways used by allied forces in the Yorktown campaign. Although population growth and urban development have erased almost all traces of the rural campsites and small taverns that once sheltered Revolutionary War soldiers, the public can still visit historic sites that tell the Washington-Rochambeau story. Strolling the green in Lebanon, Connecticut, taking a sail on the Chesapeake Bay, seeing a Revolutionary War reenactment at Colonial Williamsburg, or exploring the battlefield at Yorktown, are just a few of many opportunities to interact with history.

Travelers driving I-95 from Massachusetts to Virginia now make the trip in less than a day, and GPS systems guide them to lodging, fuel, and restaurants. It is worth remembering, however, that in colonial times, most of this land was wilderness. If not for the detailed surveys by engineers and cartographers during the allied campaign, French and American troops might not have reached Yorktown. That they did so, defeated the British, and returned north—the French to go home, the Americans to win the war—remains an impressive feat.

Having marched all the way from Williamsburg to Boston, Rochambeau's infantry sailed out of Boston Harbor for the Caribbean on Christmas Day 1782.

French forces under the comte de Rochambeau quartered in Newport from their arrival on July 18, 1780, until their departure for New York on June 11, 1781.

Lebanon provided winter quarters for some 220 of the 300 hussars of Lauzun's Legion from November 20, 1780, until June 20, 1781.

Having spent the winter of 1780-81 in and around Newburgh, Washington and the Continental Army "broke camp on June 28, and joined Rochambeau's forces near White Plains on July 4, 1781.

Generals Washington and Rochambeau arrived in Philadelphia on August 30, 1781. Their forces paraded before Congress from September 2 to 4.

The Battle off the Capes occurred near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on September 5, 1781.

On September 9-10, 1781, about 1,450 officers and men of the Continental Army, as well as about 1,200 of Rochambeau's forces, embarked at Elkton for the journey to Virginia.

Late in the afternoon of September 21, 1781, the rest of the allied forces, some 3,800 French and 200 American soldiers, sailed from Annapolis.

Having left Elkton early on September 8, Washington covered the 120 miles to Mt. Vernon in two days, arriving at his estate late on September 9, 1781.

(click for larger map)Reenforced by French forces under the marquis de St. Simon, as well as Continental Army troops under the marquis de Lafayette, the combined allied armies, 9,000 Americans and 9,000 French strong, set out for Yorktown on September 28, 1781.

On October 19, 1781, Lord Cornwallis surrendered his forces to the victorious allies.

After the siege of Yorktown, Rochambeau's forces wintered in Virginia. The troops headed north in summer 1782, continuing all the way to Boston, and departed the United States on Christmas Day 1782.

More Information

The Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route

Visit other historic sites and scenic byways along the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route. The places designated on this map are all open to the public. For locations, hours, directions, and other places of interest, visit http://www.nps.gov.

The National Park Service maintains a partnership with the National W3R Association (www.w3r-us.org). W3R is a nine-state partnership that supports the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route as a National Historic Trail and educates the public about the three-year presence of the French Expeditionary Force in the United States.

The National Park Service works with federal, state, and local agencies and private organizations along the nine-state corridor that constitutes the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route.

Source: NPS Brochure (2011)

|

Establishment Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail — March 30, 2009 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Foundation Document Overview, Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail, MA-RI-CT-NY-NJ-PA-DE-MD-VA-DC (February 2019)

Park Newsletter

2012: April • May • June • July • August • September • October • December

2013: January • February • March • April • May • June • July • August

2014: January • February • March • April • May • June • July • August • September • October • November-December

2015: January • February • March • April • May • June • July • August • September • October • November • December

Statement of National Significance: The Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route Revised Draft Report (Robert A. Selig, Goody, Clancy & Associates, January 30, 2003)

Strategic Plan Draft, Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail (October 2010, updated October 2011)

Poster: The Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route (Detailed) (October 2006)

Poster: The Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route (Historic) (October 2006)

Special Resource Study & Environmental Assessment: Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route (October 2006)

waro/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025