|

YUKON-CHARLEY RIVERS

Yukon Frontiers Historic Resource Study of the Proposed Yukon-Charley National River |

|

III. THE RUSSIAN AND ENGLISH FRONTIER

Far beyond the Han territory, late in the eighteenth century, the Russians introduced among other Natives new concepts, tools, and skills derived from a thousand years of western civilization. For the first fifty years of Russian settlement, the Han felt little impact. By the 1830's, however, word had reached them of the value of the new trading goods. Indians along the Mackenzie River, nearly two thousand miles away, exhibited such articles as Russian coins, metal combs, and copper tools and testified that foreign men traded at a post at the mouth of a great river. [1]

In fact, in 1833 the Russians had built a trading fort at St. Michael, near the mouth of the Yukon River, and had cautiously explored the lower Yukon. They eventually established a post at Nulato and traded as far up the Yukon as the Tanana River. At the same time, the British Hudson's Bay Company had slowly expanded westward. Along overland routes and up the coasts, they pushed toward Russian America. This expansion, together with the construction of permanent trading posts alarmed the Russians. Eventually, in 1839, the trading competition brought about a treaty intended to remove rivalry and friction between the two parties. [2] In the following years both countries strove to maintain the resultant good will.

Meanwhile, on the western fringes of the British trading frontier, Robert Campbell arrived at the Mackenzie River in the "land of romance and adventure". [3] In 1834, Campbell was twenty-six years old. The rugged Scottish hills of his father's sheep farm had strengthened his tall, broad-shouldered physique for the deprivations of the North American frontier. Reared a devout Presbyterian, he not only carried a Bible with him wherever he went, but professed the Protestant edict that the products of civilization could help improve the Natives' primitiveness, poverty, and misery. [4] Yet he chose the Hudson's Bay Company primarily for the challenges of exploration and living in an unknown land. [5]

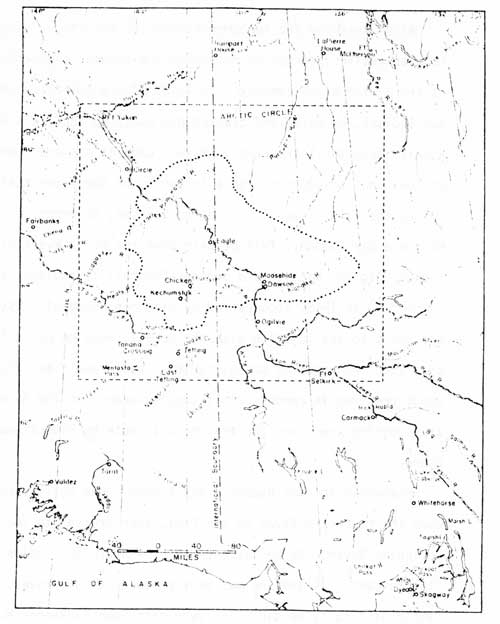

After learning the fundamentals of the fur trade, Campbell took an active interest in expanding the trading boundaries of the Hudson's Bay Company. In 1840, with a companion and two Indians, he poled and tracked his boats up the Liard River and its tributary, the Francis River, crossed the continental divide, and looked down onto a tributary of the Yukon that he called the Pelly River. Sir George Simpson Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, felt certain that the Pelly eventually flowed into the Pacific and ordered Campbell to explore it further. [6] In 1848, accompanied by nine men, Campbell descended the Pelly to its junction with the Lewes. Here he built Fort Selkirk amid rich resources of moose, caribou, bear, and fish. But trade goods remained in chronic short supply because of the hazards of transporting them over the treacherous route he himself had opened.

Meanwhile another Hudson's Bay trader, John Bell, explored down the Mackenzie River to the Peel, then crossed to the Porcupine River. As he descended it, he heard the Indians talk of "the Youcan". In 1846 he was ordered to find this river. With little difficulty he did. The very next year Alexander Hunter Murray followed this route to the mouth of the Porcupine. There, near its mouth on the Yukon River, he supervised the building of Fort Yukon. [7]

Although Alexander Murray had joined the Hudson's Bay Company only the year before, he competently constructed three log buildings surrounded by a stockade—not in fear of the Natives, but in fear of the Russians. He felt certain that the Russians had explored the Yukon to its source. [8] But more important, Murray knew that the fort trespassed on Russian soil, and he did not want to upset British-Russian relations, smoothed over by the 1839 treaty. He recorded his less-than-happy thoughts during that first year: "As I sat smoking my pipe and my face besmeared with tobacco juice to keep at bay the d—d mosquitoes still hovering in clouds around me, that my first impressions of the Youcan were anything but favorable. . . . I never saw an uglier river, everywhere low banks, apparently lately overflowed, with lakes and swamps behind, the trees too small for building, the water abominably dirty, and the current furious." [9] Nevertheless, he found the Native population larger than he had initially believed and receptive to trade. With a small experimental garden and abundant game resources, Murray came to enjoy his trading post.

The post also attracted the Han, or the Gens du fou as Murray called them. They added to their culture trade items that they had previously obtained from the Russians, either directly or through intermediaries—beads, blankets, muskets, iron knives, and metal containers. [10] These trade items, as well as general contact with English and Russian traders, caused rapid changes within their culture. Beads and blankets became frequent decorative ornaments and important items for the potlatch. Metal tools and implements replaced their aboriginal counterparts, whereas guns may have increased intertribal conflict. To obtain these trade items, the Han had to shift from fishing to a greater emphasis on hunting and trapping. [11] Thus, this first overlapping of Natives' and traders' frontiers forced adaptations upon the aboriginal inhabitants.

Meanwhile Governor Simpson, judging relations with the Russians sufficiently cordial, at last granted Robert Campbell permission to explore as much of the Pelly as he wished. Eagerly, Campbell left on June 4, 1851. Although rumors whispered that the Russians had travelled the middle Yukon, Campbell became the first recorded white man to make the trip. After two days and nights of travelling, he met a group of Indians, later known as the Han, who delivered a letter of welcome from Alexander Murray written a year earlier. Campbell named the White and Stewart Rivers for colleagues in Hudson's Bay Company. [12] On June 8, after only a four-day journey, he reached his goal—Fort Yukon. "I had thus the satisfaction of demonstrating that my conjectures from the first—in which hardly anyone concurred—were correct and that the Pelly and Youcon were identical" [13]

Campbell returned with a few trade goods to Fort Selkirk via the old route of the Porcupine, Mackenzie, and Liard Rivers. The following summer he travelled again to Fort Yukon and obtained enough trade goods to test the potential of his fort. His test never materialized. Later that summer Chilkats from the southeast coast arrived at Fort Selkirk, angry and hostile. Until the fort's construction they had enjoyed a monopoly of trade with the Indians of the upper Yukon, acting as middlemen between them and the Russian and British traders on the coast. Unable to appease the Chilkats, Campbell was lucky to escape with his life as his trading post burned. He then sought permission to rebuild the fort but he failed to convince the company managers of its importance. Discouraged and cynical, he left for Scotland. A year later, with bride in hand, he returned as a Hudson's Bay Company administrator. Never again, however, did he cross the Rockies to the Yukon. After forty-one years, the company suddenly and unjustly fired him, and he finished his life cattle ranching in Manitoba. [14]

Despite contrary rumors, the English and Russian trading frontiers still had not met. At last, however, in 1863 the Russians sent Creole Ivan Lukeen to Fort Yukon to gather information on the extent of British trade. He successfully posed as a defector from the Russian company and accomplished his mission. At the same time he went on record as the first white man to travel from the sea to the Porcupine, proving beyond a doubt that the Russian Kvichpak and the English Yukon were one great river. [15] Although other, more substantive relations may have developed between English and Russian traders, Lukeen's mission is the only well-documented connection between the two.

Further exploration soon occurred. In 1866, when the Western Union Telegraph Company attempted to find the best overland route for a European telegraph line via Canada, Russian America and Siberia, Lukeen guided the explorers Michael Lebarge and Frank Ketchum to Fort Yukon. The following summer, without Lukeen, Lebarge and Ketchum continued to explore the territory Robert Campbell had abandoned sixteen years earlier. At the ruins of Fort Selkirk they turned back and at Nulato learned that the underwater trans-Atlantic cable had made Western Union's venture pointless. Only a few months later, in March 1867, the purchase of Russian America by the United States permanently removed the Russian frontier and opened the way for still another breed of trader—the American.

Although the Russian frontier had little direct contact with the middle Yukon, it had great impact on its Natives. The Russians introduced a new material culture that the Natives eagerly adapted to their own. As they embraced facets of this new culture, they forfeited their self-reliance and independence. They became dependent upon the trader, his trading post, and his demand for fur. Any change in any of these three variables brought a corresponding change in the Native lifestyle. Thus the Russians introduced a new variant to the environment of the Natives. The British and Americans perpetuated it.

On the Pacific Coast soon after the Alaska purchase, seven men from various parts of the country formed Hutchinson, Kohl & Company which purchased the assets of the Russian American Company. Then Hutchinson, Kohl & Company took in two other groups and formed the Alaska Commercial Company which soon dominated the fur trade of Alaska. [16]

The Hudson's Bay Company found these newcomers not as appeasing, passive, or accomodating as their Russian predecessors. Instead the Americans, conditioned by two hundred years of frontier adaptations, asserted aggression, innovation, and impatience. [17] When the Americans recognized that the British were siphoning off the middle Yukon trade, they responded with thinly veiled threats of force.

The United States Army directed Captain Charles Raymond of the Corps of Engineers to determine the latitude and longitude of Fort Yukon and to report on the activities of the Hudson's Bay Company in Alaska. [18] Raymond arrived at St. Michael on the Alaska Commercial Company's ship Commodore, which had lashed to its deck a fifty-foot stern-wheel steamer, the Yukon. On July 4, 1860, the Yukon, the first of hundreds of steamboats on the Yukon, entered the river. It caused great excitement and consternation among the Natives as it "appeared to them as a huge monster, breathing fire and smoke." [19]

Raymond debarked at Fort Yukon after making celestial observations and announced to the Hudson's Bay Company that Fort Yukon stood within the boundaries of the United States. The British company obligingly sold the fort to the Alaska Commercial Company and departed. Even though the British had physically left the middle Yukon, however, their presence and influence continued to be felt. An artificial political boundary did not inhibit the free movement of either Natives or traders.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

yuch/grauman/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 29-Feb-2012