On the completion of the work of excavation and

repair of Cliff Palace, in the Mesa Verde National Park, in southern

Colorado, in charge of the writer, under the Secretary of the Interior,

he was instructed by Mr. W. H. Holmes, then Chief of the Bureau of

American Ethnology, to make an archeologic reconnaissance of the

northern part of Arizona, where a tract of land containing important

prehistoric ruins had been reserved by the President under the name

Navaho National Monument. In the following pages are considered some of

the results of that trip, a more detailed account of the ruins being

deferred to a future report, after a more extended examination shall

have been made.a Mention is made of a few objects collected, and

recommendations are submitted for future excavation and repair work on

these remarkable ruins to preserve them for examination by students and

tourists. As will appear later, a scientific study of them is important,

for they are connected with Hopi pueblos still inhabited, in which are

preserved traditions concerning the ruins and their ancient

inhabitants.

aThe author's first visit to these ruins was made in

September, 1909, and he returned to the work in the following May. A few

notes made on the latter trip on rums not observed during the former are

incorporated in this report.

The present population of Walpi, a Hopi pueblo, is

made up of descendants of various clans, whose ancestors once lived in

distant villages, now ruins, situated in various directions from its

site on the East mesa. One of the problems before the student of the

Pueblos is to locate accurately the ancestral villages, where these

clans lived in prehistoric times. From an examination of the

architecture of these villages and a study of the character of secular

and cult objects found in them, the culture of the clans that inhabited

these dwellings could be roughly determined. The culture at any epoch in

the history of the clan being known, data are available that may make

possible comparison and correlation with that which is still more

ancient: in other words, that may add a chapter to our knowledge of the

migrations of the Hopi Indians in prehistoric times.

Plate 2. INSCRIPTION HOUSE (from a photograph

by William B. Douglas)

|

The writer has already identified some of the ancient

houses of those Hopi clans that claim to have dwelt formerly south of

Walpi, on the Little Colorado near Winslow, but has not investigated the

ruins to the north, in which once lived the Snake, Horn, and Flute

clans. An investigation of the origin and migrations of this contingent

is instructive because it is claimed that these clans were among the

first to arrive at Walpi, or that they united with the previously

existing Bear clan, forming the nucleus of the population of that

pueblo.

A preliminary step in the investigation of the

culture of the clans that played a most important part in founding Walpi

and giving rise to the Hopi people would be the identification of the

houses (now ruins) of the Snake, Horn, and Flute clans, the existence of

which in the region north of Walpi is known with a greater or less

degree of certainty from Hopi legends. An archeologic study of these

ruins and of cult objects found in them would reveal some of the

prehistoric features of the culture of the ancient Snake clans. "The

ancient home of my ancestors," said the old Snake chief to the writer,

"was called Tokonabi,a which is situated not far from Navaho

mountain. If you go there, you will find ruins of their former houses."

In previous years the writer had often looked with longing eyes to the

mountains that formed the Hopi horizon on the north where these

mysterious homes of the Snake and Flute clans were said to be situated,

but had never been able to explore them. In 1909 the opportunity came to

visit this region, and while some of the ruins found may not be

identifiable with Tokonabi, they were abodes of people almost identical

in culture with the ancient Snake, Horn, and Flute clans of the

Hopi.

aThe exact situation of Tokonabi has never been identified

by archeologists. Ruins are called by the Navaho nasazi bogondi,

"houses of the nasazi." The name Tokonabi may be derived from

Navaho to, "water;" ko, contraction of bokho,

"canyon;" and the Hopi locative obi, "place of." The derivation

from Navaho boko, "coal oil," is rejected, since it is very

modern.

References to the northern ruins occur frequently in

Hopi legends of the Snake and Flute clans, and even accounts of the

great natural bridges lately seen for the first time by white people

were given years ago by Hopi familiar with legends of these families.

The writer heard the Hopi tell of their former homes among the "high

rocks" in the north and at Navaho mountain, fifteen years ago, at which

time they offered to guide him to them. The stories of the great

cave-ruins to the north were heard even earlier from the lips of the

Hopi priests by another observer. Mr. A. M. Stephen, the pioneer in Hopi

studies, informed the writer that he had learned of great ruins in the

north as far back as 1885, and Mr. Cosmos Mindeleff, aided by Mr.

Stephen, published the names of the clans which, according to the Hopi,

inhabited them.

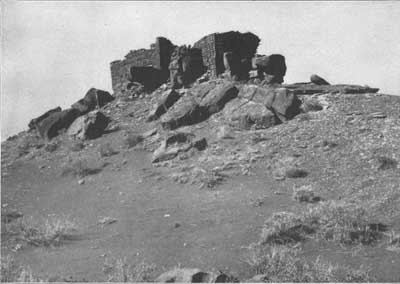

Plate 3. WUKOKI RUIN AT BLACK FALLS (a.

from the south (top); b. from the north (bottom))

|

Victor Mindeleffa summarizes the Hopi

traditions concerning Tokonabi still preserved by the Horn and Flute

clans of Walpi:

The Horn people, to which the Lenbaki [Flute]

belonged, have a legend of coming from a mountain range in the east.

Its peaks were always snow covered, and the trees

were always green. From the hillside the plains were seen, over which

roamed the deer, the antelope, and the bison, feeding on never-failing

grasses. [Possibly the Horn people were so called from an ancient home

where horned animals abounded.] Twining through these plains were

streams of bright water, beautiful to look upon. A place where none but

those who were of our people ever gained access.

This description suggests some region of the

headwaters of the Rio Grande. Like the Snake people, they tell of a

protracted migration, not of continuous travel, for they remained for

many seasons in one place, where they would plant and build permanent

houses. One of these halting places is described as a canyon with high,

steep walls, in which was a flowing stream; this, it is said, was the

Tsegi (the Navajo name for Canyon de Chelly).b Here they built a

large house in a cavernous recess, high up in the canyon wall. They tell

of devoting two years to ladder making and cutting and pecking shallow

holes up the steep rocky side by which to mount to the cavern, and three

years more were employed in building the house. . . .

The legend goes on to tell that after they had lived

there for a long time a stranger happened to stray in their vicinity,

who proved to be a Hopituh [Hopi], and said that he lived in the south.

After some stay he left and was accompanied by a party of the "Horn"

[clan], who were to visit the land occupied by their kindred Hopituh and

return with an account of them; but they never came back. After waiting

a long time another band was sent, who returned and said that the first

emissaries had found wives and had built houses on the brink of a

beautiful canyon, not far from the other Hopituh dwellings. After this

many of the Horns grew dissatisfied with their cavern home, dissensions

arose, they left their home and finally they reached Tusayan.

The early legends of the Snake clans tell how bags

containing their ancestors were dropped from a rainbow in the

neighborhood of Navaho mountain. They recount how they built a

pentagonal home and how one of their young men married a Snake girl who

gave birth to reptiles, which bit the children and compelled the people

to migrate. They left their canyon homes and went southward, building

houses at the stopping-places all the way from Navaho mountain to Walpi.

Some of these houses, probably referring to their kivas and

kihus, legends declare, were roundc and others square.

aSee A Study of Pueblo Architecture, Tusayan and Cibola, in

Eighth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology. The legend was

obtained by Mr. A. M. Stephen.

bEvidently a mistake in identification of localities.

Although the Navaho name Tsegi has persisted as the designation of

Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, there is little doubt that when the Hopi gave

to Stephen the tradition of their former life in "Tsegi," they did not

refer, as he interpreted the narration, to what is now called Canyon de

Chelly, but to Laguna canyon, likewise bordered by high cliffs, which

the Navaho also designate Tsegi. The designation Canyon de Chelly was

used by Simpson in 1810 (Sen. Ex. Doc, no. 64, 31st Cong., 1st sess.),

who wrote (p. 69, footnote): "The orthography of this word I got from

Senor Donaciano Vigil, secretary of the province, who informs me that it

is of Indian origin. Its pronunciation is chay-e."—J. W. F.

cThe circular type disappeared before they arrived in the

valley below Walpi. Legends declare that the original Snake kivas were

circular, and there are references, in legends of clans other than those

that formerly lived in the north, to circular kivas formerly used by the

Hopi.

Some of the ruins here mentioned have been known to

white men for many years. There is evidence that they have been

repeatedly visited by soldiers, prospectors, and relic hunters. The

earliest white visitor of whom there is any record was Lieutenant Bell,

of the 2d (?) Infantry, U. S. A.,a whose name, with the date

1859, is still to be seen cut on a stone in a wall of ruin A.

aProbably Lieut. William Hemphill Bell, of the Third

Infantry, United States Army.

A few years ago information was obtained from Navaho

by Richard and John Wetherill of the existence of some of the large

cliff-houses on Laguna creek and its branches; the latter has guided

several parties to them. Among other visitors in 1909 may be mentioned

Dr. Edgar L. Hewett, director of the School of American Archaeology of

the Archaeological Institute of America. A partyb from the

University of Utah, under direction of Prof. Byron Cummings, has dug

extensively in the ruins and obtained a considerable collection.

b Since the writer's return to Washington this party has

spent several months at Betatakin.

The sites of several ruins in the Navaho National

Monument,c which was created on his recommendation, have been

indicated by Mr. William B. Douglass, United States Examiner of Surveys,

General Land Office, on a map accompanying the President's proclamation

and also on a recent map issued by the General Land Office. Although his

report has not yet been published, he has collected considerable data,

including photographs of Betatakin, Kitsiel (Keetseel), and the ruin

called Inscription House, situated in the Nitsi (Neetsee) canyon. While

Mr. Douglass does not claim to be the discoverer of these ruins, credit

is due him for directing the attention of the Interior Department to the

antiquities of this region and the desirability of preserving them.

cMr. Douglass has furnished the writer the following data

from his report regarding the positions of the most important ruins in

the Navaho National Monument:

| LATITUDE | LONGITUDE |

| Kitsiel, 36° 45' 33" north. | 110° 31' 40" west. |

| Betatakin, 36° 40' 57" north. | 110° 34' 01" west. |

| Inscription House, 36° 40' 14" north. | 110° 51' 32" west. |

The two ruinsd in Nitsi (Neetsee),e

West canyon, are not yet included in the Navaho Monument, but according

to Mr. Douglass these are large ones, being 300 and 350 feet long,

respectively,f and promise a rich field for investigation. That

these ruins will yield large collections is indicated by the fact that

the several specimens of minor antiquities in a collection presented to

the Smithsonian Institution by Mr. Janus, the best of which are here

figured (pls. 15-18), came from this neighborhood, possibly from one of

these ruins.

dOne of these is designated Inscription House on Mr.

Douglass's map (p1. 22).

eAccording to one Navaho the meaning of this word is

"antelope drive," referring to the resemblance of the canyon to such a

structure.

fFor photographs of Kitsiel (p1. 1) and of Inscription House

(here p1. 2). published by courtesy in advance of Mr. Douglass's report,

the writer is indebted to the General Land Office. Acknowledgment is

made to the same office for ground plans of Kitsiel and Betatakin, which

were taken from Mr. Douglass's report.

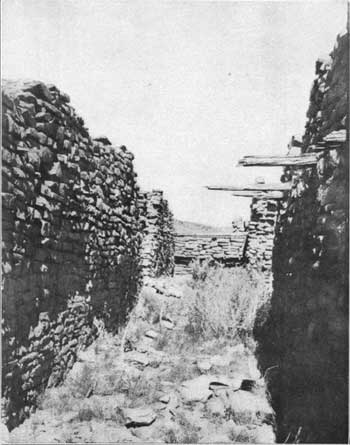

Plate 4. RUIN A, SOUTHWEST OF MARCH PASS

(a. interior (top), b. exterior (bottom))

|

The ruins in West canyon (p1. 2) are particularly

interesting from the fact that the walls of some of the rooms are built

of elongated cylinders of clay shaped like a Vienna loaf of bread. These

"bricks" consist of a bundle of twigs enveloped in red clay, which forms

a superficial covering, the "brick" being flattened on two faces. These

unusual adobes were laid like bricks, and so tenaciously were they held

together by clay mortar that in one instance the corner of a room, on

account of undermining, had fallen as a single mass. The use of

straw-strengthened adobe blocks is unknown in the construction of other

cliff-houses, although the author's investigations at Cliff Palace in

Mesa Verde National Park revealed the use of cubical clay blocks not

having the central core of twigs or sticks, and true adobes are found in

the Chelly canyon and at Awatobi. The ruins in West canyon can be

visited from either Bekishibito or Shanto, the approach from both of

these places being not difficult. There is good drinking water in West

canyon, where may be found also small areas of pasturage owned by a few

Navaho who inhabit this region. The trail by which one descends from the

rim of West canyon to the valley is steep and difficult.

One of the most interesting discoveries in West

canyon is the grove of peach trees in the valley a short distance from

the canyon wall. The existence of these trees indicates Spanish

influence. Peach trees were introduced into the Hopi country and the

Canyon de Chelly in historic times either by Spanish priests or by

refugees from the Rio Grande pueblos. They were observed in the Chelly

canyon by Simpson in 1850.

The geographical position of these ruins in relation

to Navaho mountaina leads the writer to believe that they might

have been built by the Snake clans in their migration south and west

from Tokonabi to Wukoki, but he has not yet been able to identify them

by Hopi traditions.

aHopi legends ascribe the former home of the Snake clan to

the vicinity of this mountain.

But little has appeared in print on the ruins near

Marsh pass. In former times an old government road, now seldom used, ran

through Marsh pass, and those who traveled over it had a good view of

some of these ruins. Situated far from civilization, this region has

attracted but slight attention, although it is one of the most

important, archeologically speaking, in our Southwest. Much of this part

of Arizona is covered with ruins, some of which, as "Tecolote,"b

are indicated on the United States Engineers' map of 1877. In his

excellent articlec on this region Dr. T. Mitchell Prudden gives

us no description of the interesting cliff-dwellings in or near Marsh

pass, though he writes of the ruins in the neighboring canyon: "There

are numerous small valley sites, several cliff houses, and a few

pictographs in the canyon of the Towanache,d which enters Marsh

pass from the northwest." As indicated on his map, Doctor Prudden's

route did not pass the large ruins west and south of this canyon or

those on the road to Red Lake and Tuba.

bThe Mexican Spanish name for the ground-owl, from Nahuatl

tecolotl.

cIn American Anthroplogist, N. S., V, no. 2,

1903.

dThe word bokho ("canyon") is applied by the Navaho to this

canyon; tsegi ("high rocks") is used to designate the cliffs that hem it

in.

Manifestly, the purpose of a national monument is the

preservation of important objects contained therein, and a primary

object of archeological work should be to attract to it as many visitors

and students as possible. As the country in which the Navaho National

Monument is situated is one of the least known parts of Arizona first

place will be given to a brief account of one of the routes by which the

important ruins included in the reserve may be reached.