|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

The Impact of Three Exotic Plant Species on a Potomac Island |

|

CHAPTER 1:

INTRODUCTION

The General Problem

One of the evidences of man's presence in an area is the occurrence of exotic plants. They may persist long after cultivation or other activities have ceased in the area, or they may escape husbandry and invade wild land. In either case, the exotic must have some impact upon the vegetation that is already present. Two objects cannot exist in the same spot at the same time. As a minimum impact, an exotic plant must displace an indigenous plant or occupy either a vacant habitat or niche. In either case, floristic composition of the vegetation and species absolute density have changed. The change may or may not be significant or have far-reaching ecological consequences. Although the situation is somewhat analogous to a foreign bacterium invading the human body, it is in fact a type of biological pollution of an ecosystem.

Location and Physical Description of Study Area

Theodore Roosevelt Island, located at Washington, D.C., and administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, was selected as a suitable area for studying the impact of exotic species because its human history and past land use are known, and it is a wild land area which contains exotic plant species some of which occur extensively there and elsewhere.

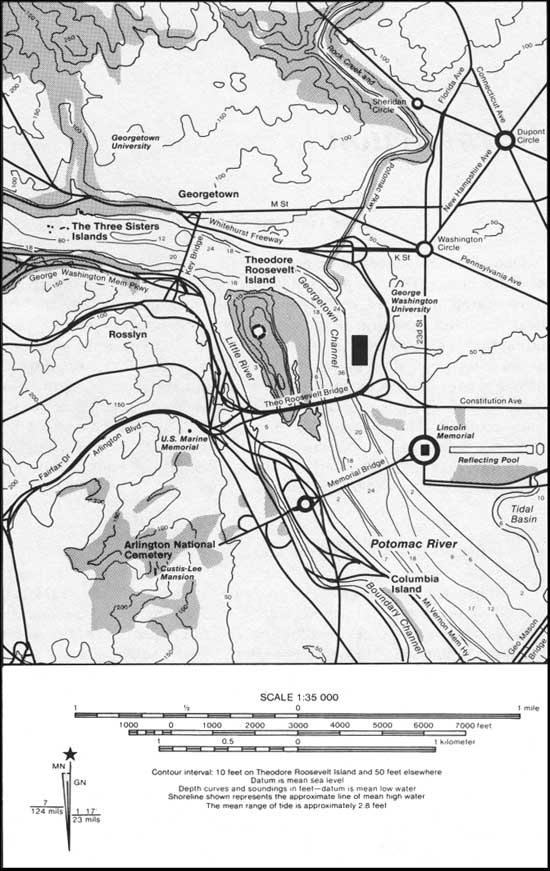

The island (Fig. 1) is located at a bend in the Potomac River and has a northwest-southeast axis (U.S. Geological Survey 1965). The 35.74-ha (88.32 acres) (National Capital Parks 1970:56) island is approximately 1.1 km (0.7 mile) long and 0.5 km (0.3 mile) wide at its widest place (U.S. Geological Survey 1965). The core of the island is micaceous schist surrounded by alluvium (Thomas 1963:1, 7). There are two topographically high areas on the island each about 13.1 m (43 ft) high (Thomas 1963:7). One high point is near the center of the island and the other is south of the center. The southwest side of the island generally slopes gradually to the alluvium, while the northeast side is generally steeper. The alluvial deposits on the northeast side form a spit (Thomas 1963:7, 21-27, 47).

|

| Fig. 1. Theodore Roosevelt Island and vicinity. |

Summary of Human History and Past Land Use

The island has had a varied history of human occupancy. The upland area was in agricultural use at least as early as 1792 by John Mason (Thomas 1963:2). The vegetation of the upland area has been disturbed periodically from that time until the island was acquired by the National Park Service in 1932 (Thomas 1963:2, 49). Aside from the construction of a highway bridge from 1959 to 1964 which passes over the southern end of the island, and a monument to Theodore Roosevelt which was constructed between 1963 and 1967 (Thomas 1963:2; U.S. National Park Service 1968:8), the last extensive vegetational disturbance took place between 1935 and 1937. This occurred mostly on the upland where 25 to 33 thousand trees and shrubs were planted (Thomas 1963:2, 49, 50). In preparation for this planting, brush, including Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica)1 and some trees, particularly boxelder (Acer negundo), were removed. The flood of March 1936 apparently did extensive damage to many of these plantings (Thomas 1963:50).

1Nomenclature of plant species follows that of Fernald (1950) unless otherwise noted.

Vegetation of the Study Area

Unpublished notes and recollections which I made for an annotated floral check list for the island as well as for a dendrological survey indicate not only that most of the plantings did not survive but that the canopy trees are essentially the result of natural invasion in almost all areas of the island. The check list includes a number of exotic plant species some of which are the result of past plantings; some have apparently invaded the island from other locations. Some of these invading species are widespread over the island.

The dendrological survey indicates that the upland of the island is a mixed deciduous forest composed primarily of Ulmus americana (American elm), Acer negundo, Morus alba (white mulberry), Prunus serotina (black cherry), Fraxinus americana (white ash), Liriodendron tulipifera (tulip tree), Quercus rubra (northern red oak), and A. saccharinum (silver maple) in about that order. In the center of the upland area is a small grove of planted Tsuga canadensis (eastern hemlock) which does not appear to be reproducing (Thomas 1963:39, 52. 53). I noticed in 1971 and 1972 that the hemlocks apparently are dying out.

The forested alluvial deposits are dominated by Acer saccharinum, Fraxinus pennsylvanica (green ash), and Salix nigra (black willow). Part of the alluvial forest is on hummocks which are not inundated in the annual floods; in this paper, this area is called "flood plain." Other parts of the alluvial forest occur in depressions and are inundated annually and sometimes daily by the tides; this area is called "swamp." Taxodium distichum (baldcypress) was planted in the 1930s (Thomas 1963:50).

The nonforested alluvial deposits are dominated by a freshwater tidal marsh. Some marsh occurs at various locations around the periphery but the largest marsh area occurs in the southeast part of the island between the upland and the spit (Thomas 1963:39). A gut or tidal creek flows south at ebb tide. The tide comes in usually twice a day, with a mean tidal range of approximately 0.9 m (2.8 ft) (National Ocean Survey 1971:228, Key Bridge, D.C.). I have observed that the marsh is not inundated every day by a high tide. The species which appear conspicuous by their abundance in the large marsh are Peltandra virginica (arrow arum), Acorus calamus (sweetflag), and Typha angustifolia (narrow-leaved cat-tail). Aspect dominance of Iris pseudacorus (European yellow iris, yellow flag) appears during its main flowering period of late May to early June. Nuphar luteum (L.) Sibth. & Sm. (Spatterdock) [N. advena (Ait.) Ait. f.] occurs extensively in the peripheral marshes.

Just north of the highway bridge, which is at the south end of the island, is a small grassy field.

The Species Selected for the Study

Because of their abundance and apparent importance, three exotic plant species were selected for ecological study: Hedera helix (English ivy), Lonicera japonica, and Iris pseudacorus.

Hedera helix (Araliaceae) is an evergreen woody vine from Europe (Gleason 1952, 2:605). This ivy is widespread in the upland and flood plain forests of the island, but there are some areas on the northeast slope that are free of the species. About 10 years ago, although English ivy was about as scattered as today, its main concentrations appeared to be around the Mason mansion site (topographic high point south of the central high point) and in the northwesterly section of the island. This ivy occurred on the island before the mass planting of the 1930s; in fact, it was recommended for preservation. Olmsted and Pope (1934: 7) say in their report:

But there are two plain evidences of former human occupation which are so agreeable in themselves and relatively so unassertive that they should be preserved rather than removed; namely the scattered areas of evergreen ground-cover of Periwinkle and English Ivy, the latter also climbing into some of the trees.

However unassertive it may have been in 1934, such was not the case by 1962 when I was collecting data for a plant check list. Today, an area of the southwest slope (northwest corner of the island), which 10 years ago was covered by Claytonia virginica (spring beauty), is now a dense ivy stand with few C. virginica. The meager evidence (concentration around the mansion site) suggests that English ivy was planted on the island when the Mason family lived there.

Lonicera japonica (Caprifoliaceae) is an evergreen woody vine from east Asia (Gleason 1952, 3:297). This species, like English ivy, is widespread in the upland and flood-plain forests of the island and absent on some sections of the northeast slope. Most of the honeysuckle stands do not appear to be as dense as the English ivy stands. One noticeable exception is south of the Mason house site and just northwest of the grassy field. This is an area where National Park Service maintenance crews removed the underbrush. Honeysuckle does not appear to be as abundant as 10 years ago. Areas that were formerly honeysuckle now seem to be mostly English ivy. The northwest part of the island appears to be such a case. Like the ivy, honeysuckle was here before the mass planting of the 1930s (Olmsted and Pope 1934:7,8). Honeysuckle seems to invade when the vegetation becomes disturbed (Thomas 1963:50). No Japanese honeysuckle occurred in 1935 on the small island (Little Island) just downstream from Theodore Roosevelt Island, but a dense stand of Acer negundo existed. The boxelders were removed apparently the same year, and by 1962 Little Island was heavily covered by honeysuckle and English ivy occurred there at least by 1962. The southern end of the flood plain of this small island is presently covered with the ivy.

Japanese honeysuckle is abundant in wild lands near Washington, D.C., other than Theodore Roosevelt Island. This is not as true of English ivy.

Iris pseudacorus (Iridaceae) is a perennial herb from Europe (Gleason 1952, 1:446) that grows in marshes. On the island, this species is scattered primarily through the araceous zone of the marshes. This zone is dominated by Peltandra virginica and Acorus calamus. This exotic species was also on the island before the mass planting of the 1930s (Olmsted and Pope 1934:9). Although the iris appears to be abundant in the large marsh on the island, it does not seem as abundant in nearby marshes of the Potomac and Anacostia rivers.

The Purpose of the Study

Answers to three questions were sought for these selected exotic species. How important are these exotics in the habitats in which they are abundant? What native and exotic species or life forms, if any, replace each other? What factors limit the degree of exotic abundance?

By studying the abundance of a given exotic in more than one habitat, the susceptibility of different vegetations to that exotic can be learned, and by studying the same habitat both with and without the exotic, the possible transformation or change from one vegetation to another can be assessed. Floristic and vegetational changes and limiting factors give information on the dynamics of exotic species impact. Limiting factors also give information which is valuable for managing and controlling the invading weed.

|

| Quadrat frame (1 x 1m) in place on a plot of English ivy (Hedera helix) in an upland Hedera block. |

|

| Ozalid type light meter on the flood plain free of exotics on northeast side of the island. Tall herb is Impatiens capensis. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

13/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 08-Oct-2008