|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Visual Preferences of Travelers Along the Blue Ridge Parkway |

|

CHAPTER ONE:

INTRODUCTION

Francis P. Noe

National Park Service

Southeast Regional Office

Atlanta, Georgia

William E. Hammitt

University of Tennessee

Knoxville, Tennessee

Background

Sightseeing is one of the most popular recreational activities in the United States. This fact is substantiated by many outdoor recreation preference studies conducted over the years. A recent survey by the Presidential Commission on Outdoor Recreation in America (New York Times, 1986) found that the most frequent outdoor activity is sightseeing. In various outdoor recreation research studies prepared by the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation (1968, 1973, 1977), sightseeing always appeared near the top of the list of user preferences. In Congress, the Interior and Insular Affairs Committee (September, 1974) predicted that by the year 2000, sightseeing would remain one of the nation's most popular outdoor recreation activities.

More site-specific surveys covering national parks throughout the United States report similar findings. A survey of visitors at Great Smoky Mountains National Park indicated that the more dilettantish tourist enjoys looking at pretty scenery and driving through pretty countryside without sacrificing his creature comforts. In almost every way, park visitors are more likely to be interested observers than active participants (ARMS Supplemental Report, Sept. 25, 1974). These findings were again confirmed in an updated review by Hammitt (1978) for the Great Smokies and nine other large national parks.

Despite the widespread evidence of the importance of sightseeing, we do not have an in-depth understanding about what constitutes a satisfying sightseeing experience—particularly as it relates to visual preference. Without knowing the visitors' most elementary sightseeing preferences, it is impossible for park managers to implement effective management and interpretive programs that will better enhance a park experience.

The sightseeing problem applies not only to the Blue Ridge Parkway but also has implications for other national parks, as the Park Service is charged with the preservation of the parks' natural resources and the protection of their aesthetic values. Almost no research has been conducted by government agencies or private scientists on this management problem. Since sightseeing remains one of the dominant activities of the American public, it is essential for us to learn as much as we can about its implications on the management of park resources.

In recent years, land use planners and managers in government agencies have become increasingly sensitive toward the public's demand for environmental attractiveness. Through the impetus of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (Public Law 91—190), the federal government is required to act as the central participant in environmental quality to assure "safe, healthful, productive, and aesthetically and culturally pleasing surroundings." The Act further states in Section 102(b) that the government will ensure that presently unquantified environmental amenities and values may be given appropriate consideration in decision-making along with economic and technical considerations.

The legal consequences of the National Environmental Policy Act have resulted in a series of cases successfully challenged by plaintiffs on aesthetic grounds. A record of these court cases, compiled by Smardon (1984), shows that the courts are now willing to accept "enjoyment of scenic beauty as a legal right." Such legal action only heightens the need to acquire information about the scenic preferences of park tourists, so that covenants of use may be developed for park lands. More importantly, since national parks are often held up as scenic standards, public preferences need to be codified. For example, in Scenic Hudson v. Federal Power Commission, the plaintiff argued that the aesthetic "qualities" of the land being defended were equal to the landscapes in national parks and monuments. Such "park status" is interpreted as being beyond any claim for "power development and industrial purposes." However, since little quantitative empirical data exist on why national park lands are viewed as aesthetically pleasing, the management of these lands will be vulnerable to legal challenges until more is known about scenic preferences.

Gaining better perspectives on what tourists see as beautiful is also important to help park managers better understand "threats" to visual quality from inside and outside a park. In the recent State of the Parks Report to Congress (1980), the National Park Service listed 73 threats reported by resource managers that "have the potential to cause significant damage to park physical resources or to seriously degrade important park values or park visitor experiences." The single most significant category mentioned by park managers was aesthetic degradation, which accounted for 25% of the total number of reported threats. Aesthetic degradation was also one of the two highest areas of recognized threats that had the greatest need for adequate documentation. However, the factual basis for documenting these threats relied heavily on the perceptions of park managers, with no reliable input from park tourists. This disparity—between those charged with managing the resource and those enjoying the resource—needs to be resolved.

In the case of the Blue Ridge Parkway, there is a special urgency since the parkway staff has already anticipated that reductions in maintenance budgets could threaten the parkway's scenic vistas and so impact the tourists' visual experiences. According to the superintendent's staff (1981), "the Blue Ridge Parkway features scenic, recreational, and cultural resources of the Southern Appalachian Highlands. It is known throughout the world for its spectacular mountain and valley vistas, quiet pastoral scenes, sparkling streams and waterfalls, and colorful flower and foliage displays. The preservation of these scenic resources and the opportunity to see them depend upon the availability of parkway management to maintain the vista windows through which they are viewed. Hand labor is the only feasible method to accomplish vista clearing work. With the ever diminishing maintenance dollar and personnel ceilings, it is not possible to accomplish this work in a timely manner."

When the parkway was constructed during the 1930s, the original decisions regarding the provision and maintenance of scenic vistas were based largely on the professional judgments of the landscape architects of the time. Scientific methods of aesthetic research were then relatively new or simply did not exist. Today, however, the field of aesthetic research has now progressed to the point where user preferences of scenic vistas can be tested more empirically. Without hard evidence of the tourists' visual preferences of scenic vistas, little support for a position of labor-intensive maintenance can be justified. To help the parkway "scrutinize all vistas to make sure that those providing little benefit are dropped from the program" (Parkway Staff, 1981), tourist preferences are necessary to make accurate and reliable judgments. The question of determining what vistas to keep, drop, or modify is at the heart of this joint research effort.

The objectives of this study were to identify:

1. The types of vistas most and least preferred by the visitors of the Blue Ridge Parkway;

2. The levels and types of maintenance required to manage the preferred vistas;

3. The predictive basis for selecting new or eliminating present vistas; and

4. The relative importance of the visual experience along the different sections of the parkway.

Study Area

The Blue Ridge Parkway was established by Congress as a unit of the National Park System on June 30, 1936. Designed especially for motor recreation, the scenic drive extends about 470 miles through the southern Appalachian Mountains of western Virginia and North Carolina. The word "Appalachian" is reported to mean "subdued mountains." It aptly describes those mountains that were formed as a result of the process of erosion, which produced a covered mantle of deeply weathered rock, rounded peaks, and a blanketed forest cover (Fennemann 1938).

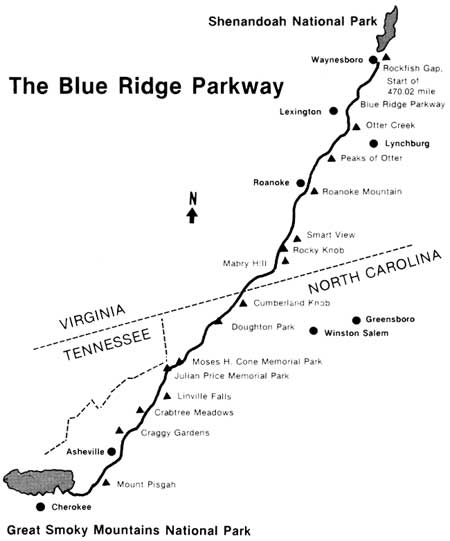

The Blue Ridge Parkway begins at Rockfish Gap, Virginia, adjacent to Shenandoah National Park, and ends at the eastern entrance of Great Smoky Mountains National Park near Cherokee, North Carolina (Fig. 1.1). The parkway traverses the crests and ridges of the Blue Ridge Province, which forms the core of the Appalachians; to the east is the Piedmont, and to the west is the Ridge and Valley Province.

Generally, the Piedmont Province is visible to the east and south, while the Ridge and Valley Province can be seen from various vantage points along the parkway's northern section. The combined physiography of these provinces provides the parkway tourist with a variety of scenic views.

Since the inception of the scenic parkway idea by Stanley Abbott in 1933 (Gignoux, 1986), the idea of a scenic route was paramount to the planners' and developers' objectives. Few topographic or detailed maps were available to offer much help. In the final analysis, "the procedure was for landscape architects and surveyors to traipse through the woods, talking with the local people about where the 'best views' were, working from one side of the ridge to the other, discussing the advantages, scenic and monetary, of locating the corridor here or there" (Blue Ridge Parkway, 1985). The parkway is nearing completion, but the process of identifying "best views" is an on-going process where maintenance of drive-offs, scenic overlooks, and vistas is concerned. The researchers contributing to this book on scenic preference, like the landscape architects of the 1930s, have surveyed the present-day users for their views, attitudes, and preferences. Since the Blue Ridge Parkway was designed to serve current users, their judgments gathered through modern survey techniques will serve as guidelines for management decisions.

|

| Figure 1.1. The Blue Ridge Parkway extends about 470 miles from Shenandoah National Park to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Methods

Two basic studies were conducted. The first investigated visitor preferences for vista landscapes along the Blue Ridge Parkway. The second evaluated visitor preferences for vegetation management at selected overlooks and roadsides along the parkway. To introduce the reader to the overall project, the rest of this chapter will briefly summarize the research methods used for each of these two studies. The chapters that follow describe the specific methods peculiar to each of the researchers' disciplines. The sample questionnaires appear in Appendices A and B.

Vista Preference Study

Study Design. The Blue Ridge Parkway is a long linear park that traverses a variety of land forms, ranging from broad ridge and valley formations in the north to high elevation mountains in the south. To represent this degree of diversity, the parkway was divided into three geographical sections: the northern, middle, and southern.

The northern section extends about 116 miles south from the southern boundary of Shenandoah National Park to the Roanoke River, and is characterized by ridges and valleys. The middle section extends 210 miles from the Roanoke River to Bear Dam Overlook. This section is primarily a mountainous plateau and provides distant views of the Piedmont area. The southern section covers the remaining 144 miles to Great Smoky Mountains National Park and consists of mostly high elevation (5000 to 6000 ft) forested mountains.

Each section of the parkway was photographically inventoried, with the representative photographs of its overlook vistas designed into a photo-questionnaire. Thus, three photo-questionnaires were developed, corresponding to the variety of overlook vistas contained within each of the three geographical sections of the parkway.

Stimuli. Initially, all developed, pulloff, and overlook vistas along the parkway were photographed with a polaroid camera, catalogued, and grouped according to scenery and vegetative themes. From this inventory a set of vista scenes was selected to represent each of the scenery and vegetative themes identified. Three or more overlook scenes representing each theme were ultimately included in a photo-questionnaire.

Each overlook vista represented in the final photo-questionnaire was re-photographed using a 35-mm camera with a 50-millimeter lens. Photographs were taken from the most popular viewing point of each overlook, looking at the dominant view. The photos were in black and white and were taken in clear weather conditions.

Photo-questionnaire. The photo-questionnaires for the vista preference study consisted of four pages of photographs, followed by ten pages of written questions. Although the photographs varied for each of the three geographic sections of the parkway, the questions remained constant in all three photo-questionnaires. The questions addressed the visitors' current parkway trip plans and use patterns, past experiences on the parkway, and various socioeconomic variables (Appendix A).

The photo-questionnaires were printed in a booklet form with an attractive cover. The photographs, 32 for each section of the parkway, were black and white, measured 2 X 3 in., and were printed eight to the page. Printed directly below each photo was a 1-5 point Likert scale for rating the visual preferences for the vista scenes (Nachmias, 1981). The preference rating scale consisted of the following categories:

1 = dislike very much

2 = dislike somewhat

3 = neutral

4 = like somewhat

5 = like very much

Respondents indicated their degree of preference for each scene by simply circling the appropriate number below each photo.

Sample. Since summer tourists make up the majority of visitors to the parkway, they were chosen as the sample population. Sampling was conducted in August and September of 1982. Six pulloff overlooks along the parkway were chosen for sampling visitors in each of the three sections. The overlooks were selected based on high visitor use. Visitors were asked to participate in the survey as they stopped their vehicles to view the vistas. A record card containing names and addresses of the visitors, the identification number of the questionnaire, and plans for their current parkway trip was completed for persons receiving a questionnaire. However, the respondents were asked to complete the questionnaire at their leisure and to mail it to us. One individual per vehicle was given a packet of materials containing a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study, a copy of the questionnaire, and a stamped, self-addressed envelope for returning the questionnaire.

Photo-questionnaires were distributed to 300 visitors in each of the three sections of the parkway. Sampling occurred on weekends and weekdays as well as during most use-hours of the day. One week after all questionnaires were distributed, a post card was sent to all respondents reminding them to return the survey. After two more weeks, a second packet of materials—including another questionnaire, a return envelope, and a cover letter—was sent to those individuals that had not returned their first questionnaire. Two weeks following this, a final letter was sent urging individuals to respond if their questionnaire still had not been returned. This follow-up procedure, as modified by Dillman et al. (1974), resulted in a return rate of 80% for all three sections of the parkway.

Vegetation Management Study

Study Design. The purpose of the vegetation management study was to obtain visitor reactions to various methods of vegetation management along the parkway. Three aspects of vegetation management were investigated: roadside grass mowing, trimming of foreground vegetation just beyond the road's edge, and cutting woody vegetation at vista overlooks. Photographs were used to represent these different techniques and levels of vegetation management. Some of the photographs were simulations, where the original photos were manipulated to represent various types of management by removing or adding vegetation.

Although we surveyed visitors in the three geographic sections of the parkway to get a representative sample, only one set of photographs was used. However, an additional version of the photo-questionnaire was developed. It included an information or message treatment page on the inside of the cover. The purpose of this treatment page was used to test the effects of a communicative message on the preferences and attitudes of participants toward vegetation management when all other factors were held constant.

Stimuli. Photographs of roadside mowing practices were obtained from a slide collection at Clemson University. Mowing alternatives ranged from no mowing, to mowing one mower width from the road's edge, to complete mowing from the edge of the road to the forest edge. Vista photos were obtained from the "vista preference study" just described. Thirty-six color photos were used, each measuring about 2 X 3 in.

Photo-questionnaire. The photo-questionnaire for the vegetation management study was printed in booklet form (Appendix B). Half of the questionnaires contained the message treatment page. The photos were printed six to the page, as three pairs of photos. The pairs of photos were matched sets in which one photo was a "control" or contained less vegetative manipulation than the other photo. The photo pairs were designed to allow a comparison of vegetation management practices. Below each photo was printed a preference scale of 1 through 5 and a brief statement. Each photo was rated using the 5-point Likert scale for how much one liked it as compared to its paired member. Following the photographs were four pages of questions that asked the respondents to give (1) their preferred vegetation management alternatives, (2) their outdoor recreation participation, (3) their leisure attitudes, and (4) their socioeconomic characteristics.

Sample. On-site sampling occurred during the last two weeks of August 1983. Popular vista pulloffs in each of the three sections of the parkway were used. Visitors were asked to participate in the study as they left their vehicles and approached the overlook areas. Six hundred visitors were surveyed, with every other person receiving a questionnaire containing the message treatment page.

As in the "vista preference study," each respondent was given a packet of materials (i.e., cover letter, photo-questionnaire, and stamped, self-addressed return envelope) and asked to complete it at his leisure. The same modified Dillman et al. (1974) system was used to encourage a good response rate. Respondents returned 504 usable questionnaires, an 84% response rate.

REFERENCES

Act of June 30, 1936. 49 Stat. 2041, as amended, establishing the Blue Ridge Parkway. 16 U.S.C. / 46 a-2, et seq.

Amusement/Recreation Marketing Service. 1974. Supplemental Report on Visitor Sampling Survey: Great Smoky Mountains National Park. New York: N.Y.

Blue Ridge Parkway. 1981. Threats to Parks Worksheet. Fiscal Year 1981 Plans. Parkway files, Asheville, N.C.

Blue Ridge Parkway. 1985. 50th Anniversary Blue Ridge Parkway. Parkway files, Asheville, N.C.

Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. 1968. The Recreational Imperative. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior.

Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. 1973. Outdoor Recreation: A Legacy For America. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior.

Dillman, D., J. Christensen, R. Brooks and E. Carpenter. 1974. Increasing mail questionnaire response: a four state comparison. American Sociological Review 39:755.

Fenneman, N.H. 1938. Physiography of Eastern United States. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co.

Gignoux, Leslie. 1986. Stanley Abbott and the design of the Blue Ridge Parkway. In B.M. Buxton and S.M. Beatty (Eds.), Blue Ridge Parkway. Boone, NC: Appalachian Consortium Press.

Hammitt, William E. 1978. Differences in Participation and Use Patterns at Some Major National Parks. Contract A-4970. Washington, D.C.: Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service. 1977. The Third Nationwide Outdoor Recreation Plan. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior.

Nachmias, N. 1981. Research Methods in the Social Sciences. New York: St. Martin's.

National Park Service. 1980. State of the Parks—1980. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior.

New York Times CXXXV (45), 1986. "Survey finds outdoor U.S. that wants nature areas kept."

Smardon, Richard. 1984. When is the pig in the parlor? The interface of legal and aesthetic considerations. Environmental Review 78(2):147-161.

U.S. Congress. 1974. Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. Sept. The Recreation Imperative. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

chap1.htm

Last Updated: 06-Dec-2007