|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Visual Preferences of Travelers Along the Blue Ridge Parkway |

|

CHAPTER FOUR:

EFFECTS OF RECREATIONAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL VALUES ON TOURISTS' SCENIC PREFERENCES

Francis P. Noe

National Park Service

Southeast Regional Office

Atlanta, Georgia

Modern road builders and engineers, like their counterparts in ancient Rome, have made value judgements about the social utility of their designs. The ancient Romans built straight roads on high ground with no curves or bends to help the marching legions avoid ambush. Modern civil engineers have designed multi-lane expressways to accommodate legions of trucks and autos and facilitate the commercial link for moving goods and materials. As a result, the American highway system has influenced the development of large urban commercial centers and has brought progress to rural areas and made our nation more accessible to travel and trade.

Besides the pragmatic economic objectives that are obviously accomplished by roads, less materialistic benefits are also achieved through the aesthetic design of roadways. Although an aesthetic experience may be less important than more practical needs, the pleasure of driving is measurably enhanced by parkways designed to improve the aesthetic quality of life. The Blue Ridge Parkway, for example, was established as a connection between the Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains National Parks to showcase the beauty and cultural lifestyle of the region to the motoring public.

How do public values and attitudes about the environment and recreation affect the appreciation of a roadway ostensibly designed for touring? At the Blue Ridge Parkway, the motoring public is exposed to a widely diverse environment that stimulates visual judgments. It takes "all of our (their) sensory experiences" to make those judgments (Buhyoff, et al., 1978). "It is important to recognize, however, that the landscape's values include more than preferences. A landscape may be valued by an individual in the sense that he or she likes it, or likes it better than others—thus the study of values as preferences. But it may also be valued by a society or culture whether or not a particular individual or group prefers it" (Andrews, 1979). Regardless of who is judging the value of the environment, "various scholars have argued that perception is an integral part of individual and group dynamics" (Rose, 1975). While both the individual and the group make acceptable judges, the research described in this chapter focuses on individual perceptions.

Value Orientations

Two commonly held values influencing the scenic judgments of individuals are thought to be their beliefs toward (1) nature and the rural environments and (2) leisure and recreation. In defining values relating to the environment, three variations have been offered as explanations. These are (a) preference, which relates to matters of individual taste (i.e., I like sightseeing better than hunting); (b) obligatory, which relates to group-shared norms (i.e., Do not start forest fires through neglect); and (c) functional, which refers to the known relationships in nature that produce benefits for mankind (i.e., Soil conservation saves streams and rivers). These three definitions represent what social scientists call attitudinal, normative, and cognitive beliefs, respectively. Attitudinal beliefs (i.e. the preference definition) are the subject of our research in this chapter.

A recent explanation of how values or attitudinal beliefs influence preferences is in the Stanford Research Institute's studies of values and lifestyles (Mitchell, 1983). That research began with "the premise that an individual's array of inner values would create specific matching patterns of outer behavior—that is, of lifestyles" (Mitchell, 1983). In essence, an individual's beliefs support certain lifestyle tastes. Our adaptation of the concept of values to the study of aesthetic evaluation in this chapter assumes that beliefs promote certain tastes that the tourists apply to scenes along a roadway. Values can help determine why tourists prefer particular scenic views along the Blue Ridge Parkway.

Perhaps the most effective way to present our research on the relationship between the tourists' attitudinal beliefs and values and their scenic preferences is to describe some of the previous research conducted in that field.

Natural Environmental Values

If a person decides to tour the Blue Ridge Parkway, his beliefs about the scenic value of nature and the environment may be a part of his motivation. In analyzing the results of an environmental preference questionnaire Kaplan (1977) found that "the person who seeks natural settings whenever possible, including when under stress, favors activities which permit expression of the preferences. Thus, he chooses activities when he can find out about things in nature." Seeking knowledge about nature through learning and deciding to visit places of natural beauty help strengthen a set of beliefs. An underlying pattern of socialization is likely to exist among parkway tourists who share a positive orientation for the natural setting. The findings of the North Atlantic Regional Water Resource Study, which summarized projects on seven different sample groups of landscape professionals students, and adults, demonstrated a pattern of preference for the natural over the man-made scene. "When the landscapes were predominantly natural or consisted of natural material such as in agricultural areas . . . the predicted rank order evaluations correlated moderately to highly with the rank orders of the seven participant subgroups" (Zube et al., 1975). Whatever the reasons for choosing the natural over the man-made, the natural scene received a higher value.

The extent to which a tendency toward the natural exists throughout history is debatable and not easily identified. Some scholars believe that the natural perspective is an "aesthetic aberration in the history of landscape taste. . . . In most canons of landscape beauty, man and his works occupy a prominent place" (Lowenthal, 1962-3). Whether at some point in history, cultures will again shift preferences to the man-made, no one is willing to venture a guess. For now, at least, "men do indeed view natural objects in ways distinct from artificial objects" (Kates, 1966-7). These differences account for the acceptance and enjoyment as well as rejection and disdain of various landscape scenes.

Studies manipulating the amount and levels of human interference using photo representation techniques of natural situations further tested the strength of preferences for man-made over purely natural scenes. The landscape scenes were quantitatively varied by the number and presence of people or man-made structures to measure their effect on landscape preferences. The results of these studies indicate "that preference tends to decrease as the levels of people and development increase" (Carls, 1974). If scenes in nature are preferred then they will probably contain few signs of man-made structural modification. While the man-made scene gives way to the natural scenes in preference, how are scenic choices influenced by the recreational preferences of individuals? We will explore this question in the following section.

Outdoor Recreation Values

Preferences for outdoor recreation activities have been the subject of increased investigation during the past two decades. Many of these studies classified individual activities into more general categories. For example, individual activities such as hiking, walking, and sightseeing were classified as appreciative recreation, while hunting and fishing were classified as consumptive recreation. However, many of these classification schemes were not always tested beyond a preliminary inquiry, and most suffered from a lack of scientific replication. Despite these problems, progress has been made toward recognizing the similarities among recreational activities.

Treating a class of recreational activities as a more general category started with preference studies. These studies supported the observation that "individuals tend to engage in a set of activities rather than one particular pursuit" (Noe et al., 1981). Individuals tend to prefer similar kinds of activities and exclude others from their consideration. In one relatively large study, "the results of the analysis indicated the degree to which people are more likely to take part in several activities within a given group of activities than to take part in those activities which fall into different groups" (Yeosting et al., 1973). In general, recreational behavior is not random behavior, and recreational activities are organized into classes of similar behavior which may also have an influence on scenic preferences.

Research was then conducted to determine if visual preferences for a parkway landscape were related to recreational classes of activity (Noe et al., 1981). The researchers found that tourists engaging in "passive outdoor experiences" have a greater liking for less manicured parkway scenes, while those who do not participate in passive outdoor activities are less likely to appreciate the natural beauty of the parkway. Passive outdoor recreation generally refers to activities that require little physical exertion, such as sightseeing, learning, and viewing visitor demonstrations. In contrast, tourists who pursue "active outdoor experiences" that require team effort and physical skill prefer a roadway scene where the vegetation is mowed and manicured. Less maintained scenes were disliked by those recreationists engaged in active sports like tennis and bicycling, which require individual skill and effort (Noe et al., 1981).

Outdoor recreational activities are often associated with "places where individuals can relax, play, engage in physical activity, get away from urban pleasures, return to nature, seek solitude, and so on" (Berry, 1976). A need for such places predisposes the public to be more receptive to environmental conditions. As a result, the protection of landscapes is often motivated by the contemplative and aesthetic values of individuals. Believing that open space is beautiful has led to recognizing that more "passive forms of recreation" are also of "relatively great importance" (Berry, 1976). Outdoor sites are valued for being quiet, peaceful, and natural as well as offering opportunities for walks among trees and affording areas containing few people. The recreationist not only defines beauty in terms of a physical environment but also finds activities like passive recreation (i.e., sightseeing) compatible with appreciating the beauty of nature.

Visual qualities characterizing a landscape as "clean, hilly, tree-studded, grassy, pleasant beautiful, natural, green, peaceful, and sunny" were also associated with a wide range of leisure activities other than just passive types (Craik, 1975). Those individuals who found it difficult to characterize the landscape belonged to fewer service, community, and religious organizations, read fewer magazines, did not participate in homecraft or glamour sports (archery, horseback riding, and water-skiing), and did not support land being used for state parks. Those individuals who were able to more easily characterize the landscape belonged to a larger number of organizations including ecological and conservation groups, and were devoted to neighborhood sports and mechanical pursuits (i.e., hobbies such as tinkering with cars, woodworking, fixing appliances, etc.). Heightened recreational use increases our facility to make visual assessments more adroitly.

Recreational experiences also alter tourists' perceptions of the environment. In a study that asked the question, "Do different recreationists perceive the natural environment in the same way?", no simple answer was found; the researchers eventually concluded that "the perception of elements in the natural surrounding depends on the kind of experience a particular recreationist group is seeking and the way in which elements of the natural surroundings enhance or detract from their experiences" (Moeller et al., 1974). For example, auto campers, wilderness hikers, and picnickers perceived their environment as more valuable than did other groups. The specialization that frequently occurs in recreational activities heightens the awareness of the value of certain site characteristics. Obviously, the more favorable a site is for an activity, the more popular and desirable it will be to that recreationist. In most instances the natural environment is favorably rated by outdoor recreational groups (Moeller et al., 1974).

Previous visual assessment studies have placed undue emphasis on a physical situation like a roadway rather than on the respondents' recreational experiences. Zube et al. (1984) found that the current trend in research is to place little emphasis on social, psychological, and recreative behavior. Most research tends to follow a behavioralist approach stressing landscape properties (stimulus) over the respondent (response). One widely followed model explains scenic attractiveness by identifying site characteristics associated with scenes in nature (Shafer et al., 1969). The site preferences of "campers" in the Adirondacks were defined by a certain proportion of vegetation, sky, lakes, waterfalls, and nonvegetation. While "camper" site preferences were explained, their recreational experiences were not explored.

Even today, the lack of knowledge about recreational experiences hampers management's understanding of how recreationists view their surroundings. In particular, studies narrowly dealing with site characteristics are criticized since they ignore recreational experiences in site assessment and evaluation. The importance of recreational values offers another potential explanation for predicting scenic preferences.

Blue Ridge Parkway Findings

The recreational, environmental, and scenic values of parkway tourists were tested and analyzed regarding their preferences toward scenes on the Blue Ridge Parkway. The tourists' frequency of visiting the parkway was also measured. Two indicators were applied to measure the level of the tourists' sightseeing involvement: stopping at overlooks and taking photographs. The number of photographs taken and the frequency of stopping appear to be related to the tourists' scenic preferences.

This analysis will concentrate only on those scenes that managers can control. Those overlooks containing vegetation that can obstruct or alter views are high priority. Factor and Alpha analysis techniques were used to locate points of similarity and dissimilarity among scenes and to discover the potential agreement of respondents among various pictorial scenes. As described by Hammitt in Chapter 2, two clusters of scenes tended to be most similar and dissimilar in their interrelationship: (1) unmaintained, vegetated vista scenes, which were the most disliked, and (2) open, multi-ridged scenes, which were highly liked by tourists. Differences in value orientations were measured against preferences for the open and unmaintained scenes.

Frequency of Stopping and Photographing

We found a positive and direct relationship between the amount of stopping and the number of photographs taken. Because stopping and photographing are interrelated, we combined both of these indicators into a single measure. The results show greater participation than we first expected. The majority of tourists felt they needed to pull off, stop, and leave their vehicle to have an adequate sightseeing experience. Thirty-four percent of the tourists stopped between five and 15 times along the parkway. Another 30% stopped between one and five times. Conversely, 34% felt no need to stop to appreciate the scenery, while the remaining 2% were undecided. To discount as trivial the pull offs and scenic vistas that allow visitors to stop and enjoy the rural landscape scenes would be an obvious miscalculation of a tourist attraction. Quite clearly, the visitors use these facilities to maximize their experience.

The number of photographs taken by the tourists indicates an effort to commemorate their visit, which they can share with their friends and family, as well as to vicariously relive for themselves. Among those tourists who stopped along the parkway and took photographs, 60% took at least one photo, and 26% of that group took between 11 and 36 or more photos. However, 40% did not take any photographs of the parkway.

Clearly, to take photographs is a dominant experience for many of the visitors. These tourists are not merely sitting behind the wheel of a vehicle and looking out the windshield. Instead, they are enjoying a sightseeing experience by participating.

Repeat Visits

To control for first-time visitors, tourists were asked about the number of visits that they had made in the past (See Appendix A). The repeat tourists became qualitatively selective in the photographs they took and where they stopped. In general, the number of photographs taken decreased as the number of repeat visits increased, and the frequency of stopping at pull-offs diminished to an average of about five stops per trip. As tourists increased their repeat visitation from one to 10 times or more in a five-year period, they reduced their photography to just a few pictures except for approximately 26% of those repeat visitors, who still took 11 or more photos. This same group also stopped the most. The amount and intensity of use exhibited by this group do not appear to diminish its enthusiasm and commitment to the Blue Ridge experience.

First-time visitors constituted 32% of our sample, while the remaining 68% were repeat visitors. The repeat visitors generally made fewer stops and took fewer photographs. In contrast, the first-time visitors were the most frequent stoppers and the most prolific photographers. Clearly, the repeat tourists are a significant majority. Given the data on the repeat visitors—i.e., their frequency of stopping and photographing—we now have a better picture of the kind of experience that a majority of those visiting the parkway call "sightseeing." That experience is highly participatory and includes certain attitudes, as we shall see.

Highway Values and Attitudes of Tourists

In a series of environmental questions seeking to explore an individual's orientation to nature, the earth, and roadways (see Appendix A), two attitudinal items related to highways stood out. The possibility of feelings toward roadways was analyzed to determine if such beliefs had anything to do with the way tourists stopped or took photographs. Since the Blue Ridge Parkway represents a different mode of transportation, we hypothesized that people who did not like ordinary highways would be among the more prolific photographers and visitors. This hypothesis proved true. Tourists with negative feelings toward ordinary highways (i.e., considering them to be uninviting and similar looking) took more photographs and stopped more frequently on the parkway than those who had a positive attitude toward highways. The tourists who disliked ordinary highways made up the majority of parkway users (over 60%). Those tourists were not just interested in a good roadway but believed it was possible to enjoy a car-touring experience. They seem to share an ideology that looks beyond the simply pragmatic, utilitarian need to move between two points in a vehicle.

This finding does not indicate a casual experience, but rather one that involves a considerable undertaking. Most of the people in this group stopped about 15 times. These tourists felt that highways are pretty dull, and almost everything looks the same along them. In contrast to the ordinary highway, the Blue Ridge Parkway offers the tourist another option.

In the data analyzed so far, we have focused upon the tourists and their level of participation. That level is surprisingly high with respect to the number of repeat tourists. Since our analysis attempts to discover what attracts tourists, we need to measure how the tourist feels about certain scenes along the Blue Ridge Parkway.

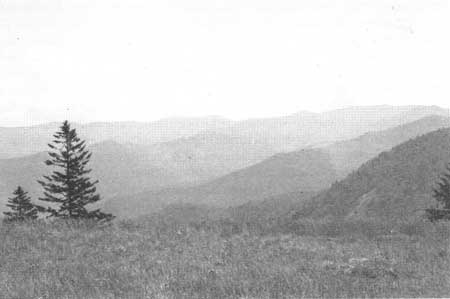

Disliked scenes contain a high degree of vegetation overgrowth and provide an unmaintained view of a vista. These "unmaintained vegetated scenes" are exemplified by a photo in Figure 4.1. Regardless of their location along the parkway, the unmaintained vegetated scenes were identified by tourists as a singular visual experience. They also happened to be the least preferred of the scenes along the Blue Ridge Parkway. At the most preferred end of the scale, a series of photographs depicting an open, multi-ridged vista, as exemplified in Figure 4.2, reveals a relatively free and open perspective to a distant view. Tourists liking a view from an open vista, with its ridges, mountains and cliffs, share a belief that most ordinary highways are generally not good for sightseeing. Conversely, tourists unimpressed with the scenic perspectives of an open vista preferred the practical utility of a highway that primarily serves as a transportation conduit.

|

| Figure 4.1. An example of an unmaintained vegetated vista. |

|

| Figure 4.2. An example of an open multi-ridged vista. |

The relationship between tourists sharing either a positive or a negative attitude toward highways and their preference for unmaintained scenes was also tested. These tests proved to be statistically insignificant. The belief in highways having a social utility but not a scenic value is perhaps more important for discriminating preferences among tourists for the more desirable rather than the least desirable vistas. While beliefs or attitudes toward a highway may not influence what tourists dislike, they do affect what tourists like.

Environmental Values and Attitudes of Tourists

In the past, the National Environmental Paradigm scale (NEP) has been used to measure the public's concern for the environment. Does a concern for the environment affect attitudes toward highways and scenery?

The NEP scale consists of 12 questions that reflect an individual's concern for nature and man's relationship with the environment (Dunlap et al., 1978). The scale explores the themes of exploitation, dominance, and disrespect for nature as opposed to living in harmony with nature without undue human interference. In adopting the NEP scale to our study, we evaluated it to determine if all the twelve items were needed. An internal reliability check of the scale was run to see if the items formed a singular dimension. Factor and Alpha analyses were performed on the data at this stage to determine precisely the most significant environmental items comprising a reliable set of scores. As a result, a modified version of the NEP scale specifying six questions was adopted (Table 4.1.).

Table 4.1. Modified NEP Environmental Scale*

| Item | Factor Score |

Alpha Value |

| The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset. | .45 | — |

| Humans have the right to modify the natural environment to suit their needs. | .35 | — |

| When humans interfere with nature it often produces disastrous consequences. | .54 | — |

| To maintain a healthy economy, we will have to develop a "steady-state" economy where industrial growth is controlled. | .37 | — |

| Humans must live in harmony with nature in order to survive. | .47 | — |

| Mankind is severely abusing the environment. | .53 | — |

| 2.43 Eigenvalue | 0.64 Total | |

*Dunlap and Van Liere (1978). | ||

Two attitudinal possibilities could result, depending upon whether a person agreed or disagreed with the scale. If a person agreed with the six scale items, he supported ecological harmony; but if he disagreed, it meant he was more apt to interfere with nature. How do these opposing attitudes reflect a person's aesthetic evaluation of scenes along the Blue Ridge Parkway? If the earlier literature review accurately reflects reality, then environmental attitudes should have some bearing upon a tourist's view of the environment. We found that tourists who believe that man should interfere with the natural environment to suit his needs dislike open vistas reflecting distant ridges, mountains, and far-off panoramas. Tourists believing that man must live in harmony with nature to survive prefer the open vistas that show natural ridgelines, mountains, and distant views. This association between environmental attitudes and preference for open vistas was statistically significant, as indicated by the Chi Square values (X2 = 10.32, df = 1, P = .001).

A significant relationship was also evident for the unmaintained scenes (X2 = 11.58, df = 1, P = .001). Tourists who believe in interfering with the environment did not like an unmaintained scene, while those who believed in living in harmony with nature felt the unmaintained scene had some value. There was a greater tolerance for unmaintained scenes among the latter. Consequently, the manager may either maintain an open vista or allow the vista to be obscured by vegetation. It matters little for those tourists who believe in living harmoniously with nature since they like both types of scenes. Presented with the choice of maintaining both open and partially obscured vistas, the manager could hardly err in satisfying this type of visitor. That the other tourist group cares little for either open or unmaintained vistas helps the manager simply direct his efforts toward satisfying those who express a preference for both types of vistas.

The extent to which vegetation should be allowed to obscure the scene is certainly a question for management to address. Since more tourists prefer the open vista, the most significant ones should be identified. Beyond that, to overstress the importance of the open vista as opposed to the unmaintained may be a disservice to those who like both types. However, the more correct position for management to take would be to emphasize the open vista at the expense of an unmaintained vista.

This information is intended to give the manager more insight into the tourist who possesses important environmental attitudes that are related to visual experiences. A manager might easily follow a recommendation of preserving open vistas but not worry too much about vistas that are obscured since most of the tourists like both. The challenge is in controlling the proper mix of open and unmaintained vistas before the manager loses the support those who prefer both types of vistas.

Recreational Values of Tourists

Some tourists may have specific recreational value expectations for visiting the parkway. Consideration must be given to the individual's specific intentions, whether it is to participate in active recreation or simply to view the scenery. Reasons for using the parkway may also be more practical, such as commuting to work or visiting friends and relatives. A series of eight questions probing a tourist's intentions for visiting the parkway proved quite successful in distinguishing expectations (see Appendix A).

The dominant reason tourists gave for visiting the parkway was for recreation, such as going on a vacation, viewing the scenery, visiting park facilities, and learning more about the area. Visiting friends and relatives or going to and from work were not important to the tourist; neither was participation in active outdoor recreational activities, such as camping, hiking, and picnicking. The predominant expectation is clearly that of obtaining a rewarding sightseeing experience during a visit.

However, do recreational expectations influence parkway participation (measured by photo-taking and stopping) as well as vista preferences? Indeed, significant relationships were found regarding the frequency of photo-taking and the number of times a tourist stopped. Expecting a recreational sightseeing experience was very important for stopping more frequently along the Blue Ridge Parkway (X2 = 33.14, df = 3, P = .001) and taking more photographs (X2 = 30.35, df = 3, P = .001). The reverse was true for those who did not seek this passive type of recreational experience; they stopped less frequently and took far fewer photos.

Most tourists, then, visited the parkway for a scenic, informed vacation involving themselves in extensive stopping and photography. We now are able to say that not only are these tourists stopping and taking photos, but they are doing so because their reasons are associated with expectations of learning about the Blue Ridge, experiencing the scenery, enjoying a vacation, attending interpretative demonstrations, and visiting facilities and visitor centers that offer information about the parkway.

A significant relationship was also found between the visitors' reasons for visiting the parkway and their preferences for scenery (X2 = 26.69, df = 1, P = .001). Tourists liking the open scene, as exemplified in Figure 4.1, were interested in scenery in general and learning about the parkway culture. But they also liked the least preferred unmaintained scenes (X2 = 7.78, df = 1, P = .005). Tourists who did not like an open scenic view did not share such sightseeing motives. As a result, management practices might be geared toward the scenic recreational experiences for tourists who like both the open and unmaintained vistas. This shared preference among the tourists certainly helps simplify the manager's decision about the level of maintenance required for scenic overlooks. Although the manager may err in providing an optimal visual experience by keeping an open visual corridor through an overlook to some distant scene, the majority of the tourists will be satisfied since they like both unmaintained and open vistas. The manager could hardly wish for a more cooperative tourist to visit the parkway.

Scenic Preferences of Tourists

Tourists were asked to respond to a wide selection of photos that represented scenes along the Blue Ridge Parkway. In addition to the photos, the tourists were asked a separate set of questions regarding their preferences for the natural vs. man-made elements of a scene (see Appendix A). Factoring and Alpha procedures were used to classify the elements in a scene. Two factors, one relating to natural elements and the other relating to the more rural farm, pastoral, or man-made elements, emerged. Statistical Factor loadings and Alpha scores are reported in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2. Stated preferences for scenes along the Blue Ridge Parkway.

| Items | Factor | |

| Natural | Rural | |

| Mountain peaks and ridges | .56 | |

| Rolling hills | .65 | |

| Flowering plants | .55 | |

| Valleys | .70 | |

| Tall trees | .62 | |

| Steep dropoff or cliffs | .41 | |

| Small towns or communities | .71 | |

| Rivers flowing through farms | .61 | |

| Farms and farm buildings | .80 | |

| Eigenvalue | 3.15 | 1.16 |

| Alpha value | .75 | .76 |

The Factor scores and Alpha levels were acceptable with regard to the natural and the man-made rural elements of scenery. We tested the relationship between the stated desirability of certain elements in a scene and their effect upon the tourist's choice of an open or unmaintained scene. In evaluating elements of the rural landscape, including the desirability of small towns, communities, farm buildings, and rivers flowing through farms, tourists who preferred developed rural scenes liked the open vista, while tourists who disliked the rural, pastoral elements did not like the open vista (X2 = 12.72, df = 1, P = .001).

The same relationship existed for the unmaintained vista. Tourists who preferred the rural scene liked the unmaintained vista. Those having no interest in viewing the rural development along the Blue Ridge Parkway had little interest in the unmaintained overlook (X2 = 3.23, df = 1, P = .07). Tourists appreciating a natural scene also preferred an unmaintained vista, while tourists not appreciating a natural scene did not like the unmaintained vista (X2 = 49.05, df = 1, P = .001). The same pattern was true for the open vistas regarding stated preference for a natural scene (X2 = 59.46, df = 1, P = .001). Clearly, a pattern of preferences toward landscape elements existed, which separates the dominant tourist groups. The similarity is striking when we look at the tourists' reasons for traveling along the Blue Ridge and their expectations and environmental attitudes.

Tourists who were sightseeing on a vacation found rural community and farm scenes highly appealing. Those who were not sightseeing did not prefer rural scenes (X2 = 13.25, df = 1, P = .001). The natural elements in a scene, such as cliffs, valleys, rolling hills, peaks, ridges, tall trees, and flowers, were also found more appealing by tourists who were sightseeing. Conversely, those not interested in sightseeing did not find those elements of a scene very desirable (X2 = 13.00, df= 1, P = .001). Tourists who are sightseeing tend to like the open and unmaintained scenes and appreciate the combined natural and rural themes that are found along the Blue Ridge Parkway. A better script could not be written for a parkway manager, since the sightseeing tourist likes the full range of scenes along the parkway.

Conclusions

If we were to exclude all consideration of attitudes, expectations, and values for visiting the parkway, management would be dealing with a general visiting public (as reported by Hammitt in Chapter 2) that prefers open scenes with views of multi-ridged vistas and expresses a dislike for scenes that obscure the distant views. However, the parkway manager cannot ask the visiting public to leave behind their preferences for scenery, their attitudes toward nature, or their reasons for visiting the parkway. The parkway manager needs to realize that part of the visiting public cares very much for all aspects of the parkway. Tourists generally express consistent positive preferences for landscape and scenery based upon their attitudes, beliefs, or motives. Another tourist segment, which is consistently negative, does not share those beliefs or motives, and the remaining tourist segment is essentially neutral.

The real question facing managers is whether to maintain vistas as open or unmaintained. The choice is quite clear. They can do both and satisfy the visiting public. The results of our analysis, however, lead inevitably to the following questions: What is the optimal ratio of open to unmaintained vistas along the parkway? Should the current ratio be changed or maintained? Should it be a two-to-one, a three-to-one, or a four-to-one ratio of open to unmaintained vistas? That ratio remains an issue. The management challenge is to determine the proper mix to continue providing satisfactory sightseeing experiences for tourists in the most cost-effective way.

REFERENCES

Andrews, Richard. 1979. Landscape values in public decisions. Paper presented at the National Conference on Applied Techniques for Analysis and Management of the Visual Resource, Incline Village, Nevada. pp. 687-688.

Berry, David. 1976. Preservation of open space and the concept of value. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 35(2):114-118.

Buhyoff, G. J., J. D. Wellman, H. Harvey, and R. A. Fraser. 1978. Landscape architects' interpretations of people's landscape preferences. Journal of Environmental Management 6(3):255-262.

Carls, Glenn. 1974. The effects of people and man-induced conditions on preferences for outdoor recreation landscape. Journal of Leisure Research 6 (Spring): 113-114

Craik, Kenneth. 1975. Individual variations in landscape description. In Zube, Brush, and Fabos (eds.) Landscape Assessment Values, Perceptions, and Resources. Stroudsburg, PA: Dowden, Hutchinson & Ross.

Dunlap, Riley, and Kent D. Van Liere. 1978. Environmental Concern. Illinois: Vance Bibliographies.

Kaplan, Rachel. 1977. Patterns of environmental preference. Environment and Behavior 9 (June):195-216.

Kates, Robert. 1966-67. The pursuit of beauty in the environment. Landscape 12 (Winter):21-5.

Lowenthal, David. 1962-63. Not every prospect pleases—what is our criterion for beauty? Landscape 12 (Winter):19-23.

Mitchell, Arnold. 1983. American Lifestyles. New York: MacMillan Publishing.

Moeller, George, Robert MacLachlan, and Douglas Morrison. 1974. Measuring perception of elements in outdoor environments. USDA Paper NE-289, Upper Darby, PA.

Noe, F. P., Gary Hampe, and Linda Malone. 1981. Outdoor recreation sporting patterns' effect on aesthetic evaluation of parkway scenes. International Journal of Sport Psychology 12(2):96-104.

Rose, M. A. 1975. Visual quality in land use control. Working Paper No. 1, School of Landscape Architecture, Syracuse, NY: State University of New York.

Shafer, Elwood, John Hamilton, and Elizabeth Schmidt. 1969. Natural land scape preferences: a predictive model. Journal of Leisure Research 1 (Winter):14-15.

Yeosting, D. R., and W. G. Beardsley. 1973. Recreation preferences, use patterns, and value estimation. In Larry Whiting (ed.) Seminar Papers, Land Use Planning Seminar: Focus on Iowa. Center for Agric. and Rural Development, Iowa St. Univ., Ames.

Zube, Ervin, David Pitt, and Thomas Anderson. 1975. Perception and prediction of scenic resource values of the northeast. In Zube, Brush, and Fabos (eds.) Landscape Assessment: Values, Perceptions, and Resources. Stroudsburg, PA: Dowden, Hutchinson, and Ross.

Zube, Ervin, James Sell, and Jonathan G. Taylor. 1984. Landscape perception: research, application, and theory. Unpublished manuscript. Univ. of Arizona, Tucson.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

chap4.htm

Last Updated: 06-Dec-2007