|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Visual Preferences of Travelers Along the Blue Ridge Parkway |

|

CHAPTER SIX:

THE USE OF INTERPRETATION TO GAIN VISITOR ACCEPTANCE OF VEGETATION MANAGEMENT

Robert H. Becker

Clemson University

Clemson, South Carolina

F. Dominic Dottavio

National Park Service

Atlanta, Georgia

Barbara L. McDonald

Institute of Community and Area Development

Athens, Georgia

To what extent can the images and preferences of landscapes be modified? To answer this question, we examined the effect of a message promoting unmowed roadsides on the visitor's preference for mowed and unmowed scenes along the Blue Ridge Parkway. Apart from the actual responses of visitors to the survey, this chapter also discusses the role of interpretation toward shaping opinion and producing desirable management outputs.

Building Images

Because interpretation is a visitor service used by a variety of personnel in a wide array of settings, there are many definitions of the term. The objectives of interpretation, according to Sharp (1982), are to assist the visitor, to accomplish management goals, and to promote public understanding and appreciation. As Machlis and Field (1984) note, the essence of interpretation is far more difficult to describe. To attempt to describe the "essence" of interpretation, Machlis and Field turned to Tilden's Interpreting Our Heritage. Tilden contends that the method of interpretation is to reveal "a larger truth that lies behind any statement of fact." Ashbaugh (1972) expands this presentation of a truth to include interpretation affecting the behavior and attitudes of the visitor.

The use of interpretation as a device for altering behavior and shaping opinions and attitudes has the potential for mischief. Questions involving visitor manipulation and the espousing of specific values are certain to raise questions about the role of the National Park Service.

Regardless of whether or not actions are directed toward gaining visitor support for Park Service management objectives, Park Service management actions project a message about the environment. For example, previous mowing patterns along the Blue Ridge Parkway presented the parkway as having a well-manicured, lawn-like roadside. Through photographic presentations and direct experience, visitors saw and expected the parkway to appear "neat." The Park Service had introduced change and had altered the message of the environment without interpreting the values of the "new message."

As Boulding (1957) points out, "The image is built up as a result of all past experience of the possessor of the image. Part of the image is history itself." He distinguishes the message as information which structures the experience. "The meaning of the message," according to Boulding, "is the change which it produces in the image." Images held by participants may affect their behavior (Becker, 1981a; Schreyer and Roggenbuck, 1979) and their enjoyment and satisfaction (Schreyer and Roggenbuck, 1979; Becker, 1979). Thus, when the message regarding roadside mowing was altered, the initial reaction was to reject the new image in favor of the old image, which had been established over time. Thus, visitors complained.

Images and the values people associate with those images need not be based on reality. Hodgson and Thayer (1980) examined a hypothesis that landscapes that purported to be natural would be given greater value by observers than landscapes that were given attributes with human-implied influences. The authors presented identical photographs to groups in three locations. Within the set of photographs, there were four experimental photographs. Half the group received photographs labeled "pond," "stream bank," "lake," and "forest"; half received photographs labeled "irrigation," "road cut," "reservoir," and "tree farm." Though the experimental photos were identical, subjects ranked the photos having human-implied influences lower than the photos with natural labels.

Becker (1980, 1981b) conducted an experiment with visitors to islands on the upper Mississippi River. Two sets of questionnaires were developed and distributed to island visitors. One set of questionnaires labeled the islands as "sand bars," natural areas along the river; the second set of questionnaires labeled the islands as "dredge spoil sites," the result of channel maintenance by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (the islands were, in fact, dredge spoil sites). When the islands were referenced as sand bars, they received a higher visitor preference rating than when classified as dredge spoil sites. While this finding was not particularly exciting, the relationship of this difference to other issues on the questionnaire was interesting. In addition to site evaluation, visitors were asked their opinions regarding the proper management function by the Corps of Engineers. Visitors who received the question with the "sand bar" phrasing were significantly more antagonistic to dredging along the upper Mississippi than were visitors given the "dredge spoil" phrasing.

As Boulding (1957) pointed out, when a new message confronts an image, that message may be rejected, but it will likely engender a conflict between the cognition of the image as held and the image as modified by the new information. Aronson (1976) termed the state of tension that occurs when a person holds two inconsistent cognitions as cognitive dissonance. This theory postulates that dissonance is uncomfortable, and as such, the individual will be motivated to reduce dissonance when it occurs. Using the upper Mississippi example, the reduction of dissonance may have occurred when the Corps of Engineers was seen as the creator of a favorite beach rather than its despoiler; however, the individual's value of the site was reduced.

The ability to effect change in an image is tied to the ability to modify an individual's opinions, attitudes, and beliefs. Katz (1960) stated that attitudes serve four functions: understanding, need satisfaction, ego-defense, and value expression. If an attitude serves multiple functions, it becomes more difficult to alter. This is consistent with Boulding's belief that images that have been developed with a broad base of reinforcement are less likely to change as a result of new messages. Rokeach (1971) and Boulanger and Smith (1973) agreed that significant changes in attitudes and values rarely occur as a result of short presentations. Thus, if a persuasive presentation effects a change in visitor response toward park management objectives, then the attitudes upon which visitor responses were based are probably not closely tied to the individual's self-perception.

The ethical issue of modifying visitor opinions and attitudes is, to some extent, answered by the relative stability of closely held attitudes and values. The issue of trying to effect change, however, should be grounded in the purpose and goals of the National Park System.

Reduced mowing along the Blue Ridge Parkway to stimulate wildflowers and increase native vegetation diversity is consistent with the idea of national parks' providing a setting with minimum influence by man. In addition to philosophical reasons for altering roadside mowing, savings in maintenance dollars and energy costs also appeared to influence the decision to alter mowing practices.

Methods

The study reported in this chapter had certain imposed limitations. First, because of the cost involved in preparing the final questionnaire, only one "treatment" message could be tested. Therefore, it was not possible to examine the different effects of a negative message, an emotional message, and an economic rationale message. The message developed was based on information from the existing marketing research literature. While the pilot instrument used large paired photographs with no written statement interpreting them, the final questionnaires used photos that were much smaller and were labeled by a caption and a rating scale below each photograph.

The communication for the pilot of this study was a written brochure with a cover page that carried the interpretive message (intended to biase the respondent toward favoring less mowing and shaggier roadside) as the treatment, a paragraph of instructions directing the respondent to select the photograph he preferred, and a set of ten paired 5" x 7" color photographs depicting mowed and unmowed scenes along the Blue Ridge Parkway (see Appendix B).

The interpretive message for this study involved two concepts which were expected to influence visitors to the Blue Ridge Parkway. First, the concept of natural beauty attempted to define a norm associating the parkway with being "natural." The idea that mowing threatens this concept was also presented. The second concept was to stress the amount of money saved if mowing were reduced. This rationalistic argument was introduced to reference mowing as not only a threat to the concept of a "natural" roadside along the Blue Ridge Parkway, but a threat which was human-induced and human-controlled. The message was reinforced with a series of three pictures showing a scene in transition from highly manicured to "natural" or unmowed. The portion of the message tied to natural, unmowed qualities was cited from Aldo Leopold's A Sand County Almanac. This reference to a familiar authority was intended to make the emotional argument the proper orientation for parkway visitors. Finally, to tie the two concepts together, we developed a catch phrase—"There is an economy in natural things"—as the closing line on the interpretive message. (The messages given to the treatment study groups are shown in Appendix B).

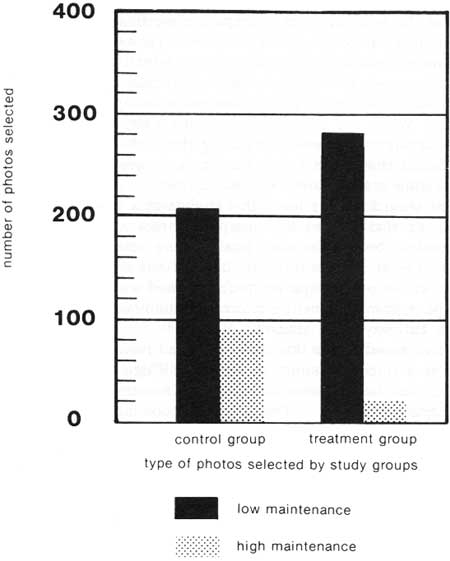

The message was pilot tested with students at Clemson University using 10 pairs of photographs. Sixty students in three classes were given the instrument. Thirty booklets had the interpretive message, and 30 did not. The students were asked to examine each pair of photographs and check the one they most preferred. Each respondent, therefore, identified 10 photographs with each of the two groups having 30 total selections. Figure 6.1 is a graph of the photographs with lower maintenance. The treatment group preferred the low maintenance photos at a ratio of 1.37:1 over the control group, possibly because of the presence of wildflowers in a number of photographs. Based upon this pilot test, the interpretive message was forwarded to the University of Tennessee for inclusion in an on-site study of visitor attitudes toward vegetation management on the Blue Ridge Parkway.

|

| Figure 6.1. Preference for roadside maintenance. |

The field study used a photo-questionnaire containing a series of 18 photo-pairs of scenes photographed over the last 30 years along the Blue Ridge Parkway. The study used eight pairs of photographs contrasting various degrees of roadside mowing and 10 pairs depicting burning, shrub removal, and tree removal. A number of photos were modified by scientists of the State University of New York at Syracuse to simulate various stages of tree and shrub growth. A detailed description of the field application is given in Chapter 1.

A chi-square analysis was used to test for association between respondents' preferences for specific photographs and exposure to the interpretive message and to test for association between respondents stated opinions regarding vegetation management practices and their exposure to the interpretive message.

Results

Tables 6.1 and 6.2 give the scores for the analysis of photographs. The only significant associations involved photographs depicting mowing practices. None of the respondents' reactions to photographs involving burning, shrub removal, or tree removal was affected by the introduction of the interpretive message. One photo in six of the eight mowing pairs was affected by the interpretive message. In one pair both photos were affected. Of the eight mowing photographs showing significant association, six involved high intensity maintenance, and two involved low intensity maintenance. The pattern of association followed the results of the Clemson pilot study. Respondents exposed to the brief interpretive message exhibited less approval of and less preference for the photos showing more mowing than for photos showing less mowing.

Table 6.1. Chi-square values for the presence of the interpretive message and preference for vegetation management practices as depicted by the photo questionnaire1 (see Appendix B).

| Photo# | Photo Caption | Chi-square Value | |

| 1a No mowing beyond guardrail | 1.62 | N.S. | |

| 1b Mowing to and beyond guardrail | .57 | N.S. | |

| 2a Mowed one mower width from roadside | 2.57 | N.S. | |

| 2b Mowed to treeline | 10.79 | * | |

| 3a No mowing | 4.26 | N.S. | |

| 3b Complete mowing into treeline | 9.92 | * | |

| 4a Vegetation not mowed around sign | 7.36 | * | |

| 4b Vegetation mowed around & beyond sign | 15.90 | * | |

| 5a Shrub vegetation in near foreground | .10 | N.S. | |

| 5b Shrubs managed by controlled burning | .37 | N.S. | |

| 6a Mowed one mower width from roadside | 2.93 | N.S. | |

| 6b Mowing complete to treeline | 12.94 | * | |

| 7a Mowing to treeline | 6.61 | * | |

| 7b Mowed one mower width from roadside | 1.79 | N.S. | |

| 8a Mowed only at mid-summer | 21.68 | * | |

| 8b Mowed every three weeks | 5.39 | N.S. | |

| 9a Only roadside shoulder mowed | 1.56 | N.S. | |

| 9b Mowed to fenceline and beyond | 6.60 | * | |

| 10a Trees closing in the scenic vista | 2.25 | N.S. | |

| 10b Low shrubs in distant foreground | 3.67 | N.S. | |

| 11a Vista with some trees in foreground | 1.81 | N.S. | |

| 11b Trees removed from foreground in vista | .76 | N.S | |

| 12a Foreground trees in vista | 1.74 | N.S. | |

| 12b No foreground trees in vista | 1.51 | N.S. | |

| 13a Scene with foreground trees | 2.87 | N.S. | |

| 13b Foreground trees completely removed | 2.66 | N.S. | |

| 14a Hardwood and conifer (evergreen) trees present | 4.41 | N.S. | |

| 14b Hardwoods cut to emphasize conifers | 2.43 | N.S. | |

| 15a Shrubs in foreground | .49 | N.S. | |

| 15b Shrubs removed by cutting & controlled burning | 1.64 | N.S. | |

| 16a Trees closing in vista more than 50% | 3.09 | N.S. | |

| 16b Selective cutting to re-open vista | 1.47 | N.S. | |

| 17a Low shrubs in distant foreground | 2.38 | N.S. | |

| 17b Mowing and cutting of foreground vegetation | 2.63 | N.S. | |

| 18a Original scene with edge trees | 1.56 | N.S. | |

| 18b Single edge tree removed | 1.74 | N.S. | |

1For photo analysis the cells were collapsed into: "not at all" "a little" and "somewhat" "quite a bit" and "very much" *Indicates significance beyond the Alpha .05 level. | |||

Table 6.2. Chi-square values for the presence of the interpretive message and preference for vegetation management practices as depicted by the seven point scale questionnaire (see Appendix B).

| Descriptive Item |

X2 Value 6 df | |

| I. The roadside grass should be mowed: | ||

| 1. weekly, like a lawn | 14.69 | * |

| 2. every two weeks, when 3-6 inches tall | 13.40 | * |

| 3. once per month, when at least 10 inches tall | 5.57 | N.S. |

| 4. once in the Fall after the wildflowers are through blooming | 11.24 | N.S. |

| 5. only one mower width (7 feet) from the edge of the road surface | 3.79 | N.S. |

| 6. two mower widths (14 feet) from the road's edge | 11.25 | N.S. |

| 7. from the road's edge to the ditch or swale | 13.67 | * |

| 8. from the road's edge to the treeline | 23.77 | * |

| 9. as little as possible, only when necessary to maintain driver safety and help prevent grass fires | 10.53 | N.S. |

| II. Shrubs and trees at pull-off vistas should be cut or trimmed: | ||

| 10. annually to maintain a completely clear view | 8.07 | N.S. |

| 11. every 5 to 7 years, before the shrubs in the foreground block much of the view | 9.19 | N.S. |

| 12. just often enough so that no more than 1/3 of the view is blocked | 5.66 | N.S. |

*Indicates significance beyond the Alpha .05 level. | ||

Similar results were found through the analysis of the vegetation management survey. The only statements associated with the interpretive message dealt with mowing. Among the mowing statements only those suggesting intensive mowing prompted significantly different responses between the two groups. Weekly mowing, mowing every two weeks or when the grasses are 3 to 6 in. tall, mowing from the road's edge to the ditch or swale, and mowing from the road's edge to the tree line had significantly less support from the group exposed to the interpretive message. Management alternatives suggesting less intensive mowing regimes exhibited no significant difference between the two respondent groups. Examples of alternative regimes are as follows: mowing when the grass was taller than 10 in., once in the fall after the wildflowers have bloomed, only one or two mower widths from the road's edge, and mowing as little as possible and then only to maintain driver safety.

Discussion

Since the Clemson pilot test involved photographs depicting only mowed and unmowed scenes, the effects of a message supporting less mowing on visitor opinions and preferences toward other vegetation management alternatives were uncertain. We hypothesized that the message would bias the respondent toward a more generalized definition of "natural" and would result in recipients of the message supporting less human intervention and a lower intensity of vegetation management. However, this did not occur. The message supporting less mowing activity only affected the respondents' opinions toward mowing.

If interpretive messages can be developed to garner support and shape public opinion toward specific actions without being generalized to other management activities, then potential conflicts created when modifying visitor preferences are minimized. For example, one may wish to reduce mowing for the sake of fuel/dollar savings or of freeing labor support for other activities and still wish to introduce controlled burns to suppress herbaceous vegetation or remove trees to open up vistas. It would not be helpful to introduce a program to increase support for less mowing if it created a negative reaction to desired vegetation management programs The results from this study suggest that a precise message can achieve specific results.

As previously mentioned, the ability to affect an attitude depends on the importance of that attitude to the individual's self-concept. Attitudes and opinions regarding vegetative management in a national park may not be important to the individual's self-concept, but it may be tied to a person's definition of "natural" and his image of the role of naturalness in park settings. If the interpretive message created a conflict between the image of the Blue Ridge Parkway as having a well groomed roadside and the role of a national park as presenting nature with minimum human influence, that dissonance was reduced through allowing a selective reevaluation of the values of mowing. Proponents of the theory of cognitive dissonance support this form of incremental reduction of tension (Aronson, 1976).

However, what about visitor complaints? Any change will usually draw dissatisfaction from some sectors of the public. If we examine the preferences for mowing practices along the Blue Ridge Parkway, we may gain insight into the intensity of public reaction toward mowing practices. About 12% of the respondents who did not receive the interpretive message made statements of "not at all" liking low maintenance mowing photographs. About 34% of the respondents who did receive the interpretive message made statements of "not at all" liking high maintenance mowing photographs. If we assume that complaints regarding management of the parkway will come from those expressing a negative rather than a positive opinion, then we stand a 300% greater chance of receiving complaints of intensive roadside mowing from visitors who value a more natural, less-managed roadside. Visitors who were not exposed to the interpretive message were a third less bothered by the natural roadside than the exposed group was toward the manicured roadside. While this comparison is less intense than the difference between the Clemson pilot groups, it is more likely to reflect the realities of visitors' opinions at the Blue Ridge Parkway.

Conclusions

Behavior, according to Boulding (1957), depends on the image that is formed from messages interpreted by the individual. In this light, interpretation is a powerful tool. An interpretive program not only enriches the experience of the visitor to the park but also explains the management roles of the National Park Service.

The results of this study and the previous work by Burris-Bammel (1978); Geller et al. (1982); Oliver et al. (1985), and others suggest that information has the capacity to modify attitudes and opinions. Given the substantial public investment in the maintenance and operation of the National Park System, it would be prudent to implement a public information program to market specific Park Service programs. The National Park Service should take its cue from the private sector: marketing an image can reinforce a desired image. The images can build constituent support, reduce unnecessary conflict, and produce a greater visitor understanding of the objectives of the National Park Service.

REFERENCES

Aronson, R. 1976. The Social Animal. New York: Freeman Press.

Ashbaugh, B. L. 1972. New interpretive methods and techniques. In Schoenfeld, C. (Ed.) Interpreting Environmental Issues. Madison, WI: Deinbar Educational Research Services, Inc., 1972.

Becker, R. H. 1979. Travel compatibility on the upper Mississippi River. Journal of Travel Research 18(1): 33-41.

Becker, R. H. 1980. Dredged spoil: an identity problem, not a terminology problem. Journal of Environmental Education 12:1.

Becker, R. H. 1981a. User reaction to wild and scenic river designation. Water Resources Bulletin 17(4): 623-26.

Becker, R. H. 1981b. Displacement of recreational users between the lower St. Croix and upper Mississippi Rivers. Journal of Environmental Management 13(4):259-267.

Boulanger, F D., and J. P. Smith. 1973. Educational principles and techniques for interpreters. USDA Forest Service Tech. Report, PNW-9, Portland, OR.

Geller, E. S., R. A. Winett, and P. B. Everett. 1982. Preserving the Environment: New Strategies for Behavior Change. New York: Pergamon Press.

Hodgson, R. W., and R. L. Thayer. 1980. Implied human influences reduce landscape beauty. Landscape Planning 7:171-179.

Jacob, G. 1977. Conflict in outdoor recreation—the search for understanding. Utah Tourism and Recreation Review 6(4): 1-5.

Katz, D. 1960. The functional approach to the study of attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly 6:248-268.

Leopold, A. 1984. A Sand County Almanac. New York: Ballantine Books.

Machlis, G. E., and D. R. Field. 1984. On Interpretation. Corvallis, OR: Oregon St. University Press.

Oliver, S. S., J. W. Roggenbuck, and A. E. Watson. 1985. Education to reduce impacts in forest campgrounds. Journal of Forestry 83(4): 234-236.

Rokeach, M. 1971. Long-range experimental modification of values, attitudes, and behavior. American Psychology 26(5):453-459.

Schreyer, R., and J. Roggenbuck. 1979. Visitor images of national parks: the influence of social definitions of place upon perceptions and behavior. Paper presented at the Second Conf. on Scientific Research in the National Parks, Nov. 28.

Sharp, G. 1982. Interpreting the Environment. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Tilden, F 1967. Interpreting Our Heritage. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

chap6.htm

Last Updated: 06-Dec-2007