|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Mountain Goats in Olympic National Park: Biology and Management of an Introduced Species |

|

| Mountain Goat Herbivory |

CHAPTER 9:

Interactions Among Herbivores, Plants, and Soils

E. G. Schreiner

Evidence of animal presence was recorded in the sample plots used to classify plant communities in mountain goat summer range (Appendix A1).12 Scat piles, tracks, wallow or bedding sites, and marmot dens found in each plot were counted. In addition, the number of wallow or bedding sites and marmot dens within 50 m of each plot and the number of trails crossing each plot were tallied. A grazing index for each plant species was obtained by estimating the proportion of plants with evidence of substantial grazing in each plot (Appendix A1). An individual plant was considered to be substantially grazed only if at least 25% of the foliage or stems had been cropped. It was not our intent to estimate the amount of standing crop removed by herbivores. Instead, we sought to create an index of grazing that could be compared among plots, areas, and plant communities.

Herbivore grazing was assessed using several parameters (Appendix A1). Average grazing represented the intensity of grazing on individual plots (grazing index averaged for all species in a plot). Percent of species grazed (PSG) was calculated by comparing the number of species with evidence of substantial grazing to the total number of species in a plot. Values of PSG greater than 50% showed that herbivores grazed a majority of the species present in a plot, and values less than 50% indicated that herbivores were more selective, grazing relatively few of the species present within a plot. A general index of plant species selection by herbivores was calculated by dividing grazing frequency by plant frequency in all plots. This measured how often a species was grazed relative to its availability. Pfitsch and Bliss (1985) described a similar index called species relative grazing frequency (SRGF). They classified species as preferred (SRGF ≥50) or avoided (SRGF ≤25). However, because they did not consider the overall availability of forage species, their index did not actually provide an estimate of relative preference or avoidance in the conventional sense (Crawley 1983). To allow comparisons with their work (and so we could use their preferred and avoided species in analyses), we used similar criteria but have classified species as selected (SRGF ≥50) or nonselected (SRGF ≤25) using our plot data.

12The number of plots analyzed here does not always match the number described in Appendixes A1 and A2 (plant community methods and descriptions) because we did not include the few plots with missing herbivory data (e.g.. number of wallows). Plots with missing herbivory data still contained valid plant cover data that were used for plant community classification.

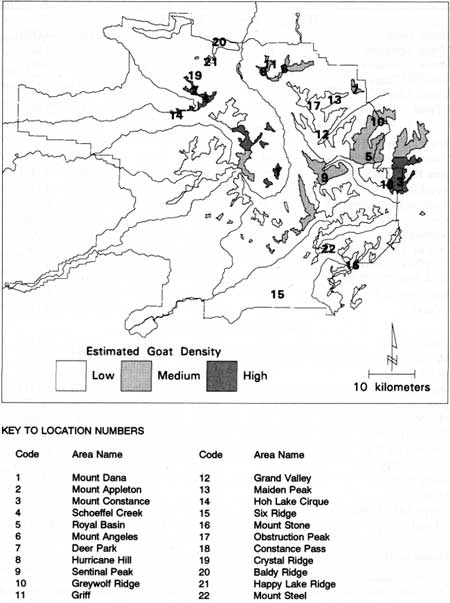

An index of the frequency with which each herbivore species used plant communities was created. The three species of ungulates (elk, deer, goats) were considered to have been present in a plot if their pellet groups, tracks, or wallow or bedding sites occurred. Marmots were considered present if a den was located. We also tallied the number of wallow or bedding sites and marmot dens within 50 m of a plot. Tabulations were necessarily biased in favor of ungulates because their sign was most prominent. Marmot activity was underestimated because only dens were used as an indicator of their presence even though tracks and scat piles were noted. Most evidence of mammals smaller than marmots resulted from direct observations, holes, or mounds of scat from winter activity. Twenty-two areas were classified into three categories of estimated goat density (Fig. 32): high (>3 goats/km2), medium (1-3 goats/km2), and low (<1 goat/km2).

|

| Fig. 32. Location of study areas in relation to estimated mountain goat density; from National Park Service (1987). (click on image for a PDF version) |

Patterns of Herbivore Sign

Considerable evidence of animal activity was observed. Herbivores included elk, mountain goats, deer, marmots, chipmunks (Tamias spp.), pocket gophers, voles (Microtus spp.), mountain beaver (Aplodontia rufa), and snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus). In addition, weasels (Mustela spp.), black bear, and coyotes or their sign were observed in five plots. Insect herbivory was noted everywhere but did not seem to account for the removal of large quantities of plant biomass.

Evidence of mountain goats was found in every sample area (Table 24). Goat pellet groups, tracks, or wallows occurred in 229 (33%) plots and within 50 m of 310 (44%). The proportion of plots with goat sign was 38% in high, 51% in medium, and 8% in low goat density areas. Marmot dens were found inside 33 (5%) and outside (within 50 m) of 170 (24%) plots in 16 of the 22 study areas. There was no obvious relation between goat density and the number of plots with marmot dens.

Sign of elk and deer occurred regularly in and around plots (Table 24). Deer and unidentified ungulate sign was observed with the highest frequency, occurring in 82 (12%) of the plots. Elk sign was encountered in only four sample areas but was locally abundant. At Hoh Lake, for example, 39% of the plots contained elk sign. Similarly, 57% of the plots at Schoeffel Creek haul elk sign. Sign of other species including bear, mountain beaver, voles, chipmunks, and snowshoe hare was encountered infrequently compared with that of ungulates.

Table 24. Number of plots (%), by species, with an herbivore index (HI) greater than zero. Mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus) density estimates, except for Mount Angeles 1982 and Deer Park 1988, are from National Park Service (1987).

| Area | n | Goats | Marmots | Elk | Deera |

| High goat density(>3 goats/km2) | |||||

| Mount Dana | 189 | 85(45) | 3(2) | 0(0) | 24(13) |

| Mount Appleton | 86 | 26(30) | 9(10) | 3(3) | 2(2) |

| Mount Constance | 16 | 5(31) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Schoeffel Creek | 14 | 1(7) | 3(21) | 8(57) | 1(7) |

| Mount Angelesb(1982) | 7 | 2(29) | |||

| Total | 312 | 119(38) | 15(5) | 11(4) | 27(9) |

Medium goat density(1-3 goats/km2) | |||||

| Royal Basin (1981) | 53 | 12(23) | |||

| Mount Angeles (1985-86)c | 44 | 26(59) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 5(11) |

| Deer Park (1985-86)c | 25 | 12(48) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 4(16) |

| Royal Basin (1983) | 29 | 26(90) | 3(10) | 0(0) | 1(3) |

| Hurricane Hill (1985-86)c | 6 | 2(33) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Mount Angeles (1985) | 7 | 7(100) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Sentinel Peak | 5 | 4(80) | 1(20) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Greywolf Ridge | 4 | 1(25) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Deer Park(1984) | 3 | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 1(33) |

| Griff Peak(1985-86)c | 3 | 2(67) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 1(33) |

| Hurricane Hill | 2 | 1(50) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Total | 181 | 93(51) | 4(2) | 0(0) | 12(7) |

Low goat density(<1 goat/km2) | |||||

| Grand Valley | 97 | 2(2) | 9(9) | 0(0) | 17(18) |

| Maiden Peak | 23 | 1(4) | 3(13) | 0(0) | 9(39) |

| Hoh Lake Cirque | 23 | 0(0) | 2(9) | 9(39) | 9(39) |

| Six Ridge | 11 | 0(0) | 0(0) | 3(27) | 2(18) |

| Constance Pass | 12 | 3(25) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Mount Stone | 9 | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Deer Park(1988) | 8 | 1(13) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 5(63) |

| Obstruction Peak | 8 | 1(13) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Crystal Ridge | 7 | 7(100) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Baldy Ridge | 4 | 1(25) | 1(25) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Mount Steel | 2 | 0(0) | 1(50) | 0(0) | 1(50) |

| Happy Lake Ridge | 2 | 1(50) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Total | 206 | 17(8) | 16(8) | 12(6) | 43(21) |

| Grand total | 699 | 229(33) | 35(5) | 23(3) | 82(12) |

aIncludes unidentified ungulates. bPlace names that appear more than once reflect goat density at the time of sampling (i.e., goat density changed between sample years). cAstragalus australis var. olympicus plots. | |||||

The larger sample size afforded by counting wallows and marmot dens within 50 m of plots increased the proportion of plots with evidence of the four herbivores. Marmot dens were observed near 27% of high, 17% of medium, and 27% of low goat density plots; goat wallows or beds were found near 68% of high, 49% of medium, and 4% of low-density plots. The percentage of plots with elk, deer, and unidentified ungulate wallows or beds within 50 m of plots was generally low except at Hoh Lake. Eleven wallows outside of plots at Hoh Lake were identified as deer and unidentified ungulate—we assume elk were responsible.

Herbivores and Soil Disturbance

The most conspicuous soil disturbances encountered were produced by wallowing and bedding—mostly by goats. Goat wallow or bed sites occurred high on slopes and had expansive views, presumably so that predators had little opportunity to surprise wallowing or resting animals. The typical wallow was a flat spot of exposed mineral soil where surface rocks had been removed and any vegetation present had been eliminated. Most wallows were 1-3 m2 with the disturbed area extending an additional 1-2 m downslope. Wallows up to 20 m2 also were encountered. More than 700 wallows were counted most were in high and medium goat density areas (Table 25). Soil disturbances accompanied by elk, deer, and unidentified ungulate sign occurred mostly in low goat density areas. More than 100 elk, deer, and unidentified ungulate wallows were counted—76 were at Hoh Lake (low goat density) where elk use prevailed.

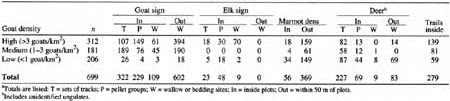

Table 25. Animal sign found inside or within 50 m of

plots in mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus) summer range of

Olympic National Park.a

(click on image for a PDF version)

The number and frequency of tracks, trails, and pellet groups in each area were a rough measure of trampling disturbance. We could not determine which large herbivore created trails, but patterns suggested that goats were often responsible. We counted 139 trails crossing 312 plots in high goat density areas and 59 crossing 206 plots in low density areas. Similarly, 149 goat pellet groups were tallied in high density plots compared to only 4 In low density plots. Deer and unidentified ungulate tracks exhibited no pattern with goat density; 82 sets of tracks were tallied in high, 58 in medium, and 87 in low goat density plots.

Herbivore—Plant Community Relations

All 16 plant communities were used by herbivores (Table 26). Mountain goat sign was present with the highest frequency followed by deer and unidentified ungulate, marmots, elk, and small mammals. Deer and unidentified ungulate sign was encountered in all community types, and mountain goat sign was found in all but one community type. Mountain goat sign was encountered twice as often as that of any other herbivore in 12 of the 16 community types.

Table 26. Number of plots (%), by plant community type, with an herbivore index greater than zero in mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus) summer range in Olympic National Park.

| Community type | n | Goats | Marmots | Elk | Deer |

| Scree | |||||

| Astragalus | 50 | 28 (56) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (8) |

| Phacelia | 41 | 17(41) | 5 (12) | 3 (7) | 7 (17) |

| Delphinium | 13 | 6 (46) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | l (8) |

| Senecio | 14 | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (14) |

| Phlox diffusa | |||||

| Potentilla | 45 | 12 (27) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (13) |

| Festuca | 44 | 9 (20) | 2 (5) | 4 (9) | 11 (25) |

| Carex phaeocephala | 42 | 11 (26) | l (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (5) |

| Juniperus | 42 | 14 (33) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 3 (7) |

| Pachistima—Sedum | 76 | 24 (32) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) |

| Pachistima—Phacelia | 15 | 7 (47) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 2 (13) |

| Carex spectabilis | |||||

| Valeriana | 39 | 8 (21) | 6 (15) | 6 (15) | 4 (10) |

| Vaccinium | 30 | 9 (30) | 4 (13) | 3 (10) | 4 (13) |

| Lupinus | 94 | 31 (33) | 12 (13) | 0 (0) | 23 (24) |

| Phyllodoce | 56 | 23 (41) | 3 (5) | 3 (5) | 7 (13) |

| Cassiope | 34 | 17 (50) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) |

| Late snowmelt | |||||

| Luetkea—Saxifraga | 5 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) |

| Total | 640 | 217 (34) | 35 (5) | 22 (3) | 82 (13) |

aIncludes unidentified ungulates. | |||||

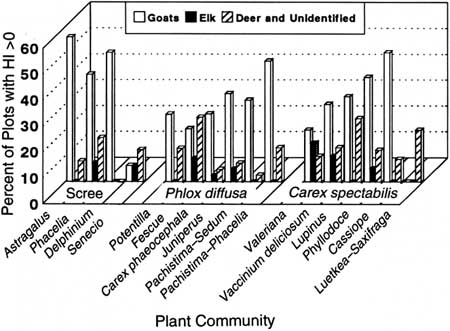

We found no strong pattern between the occurrence of goat or deer and unidentified ungulate sign and plant community type in goat summer range (Fig. 33). Evidence of mountain goats was observed in more than 40% of the plots in some communities and very little or not at all in others. Elk sign was less widely distributed among community types and was most often encountered in three of the Carex spectabilis communities and the Phacelia scree community type.

|

| Fig. 33. Percentage of plots with an herbivore index (HI) >0 for three species of ungulates by community type. |

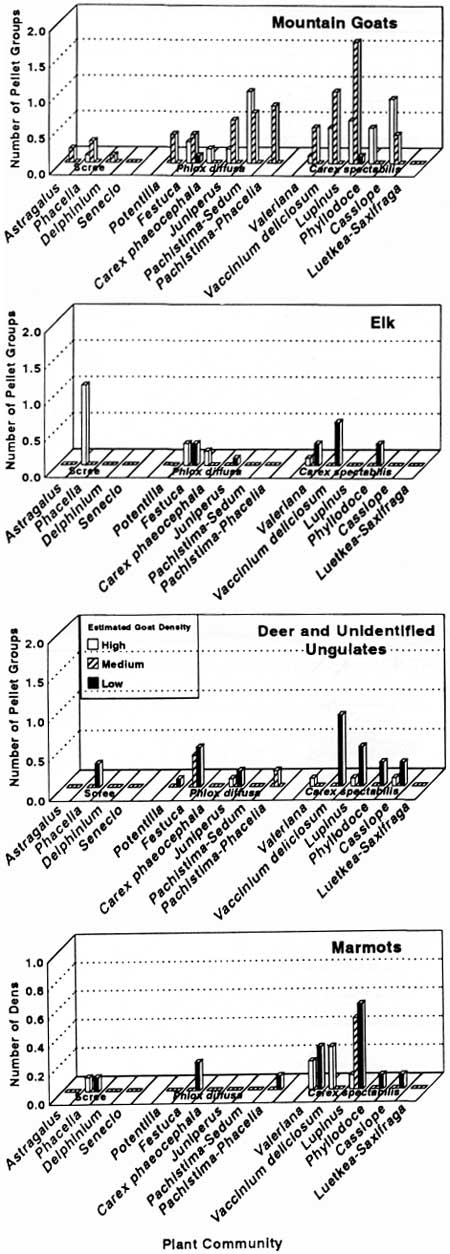

The distribution of ungulate pellet groups and marmot dens among community types (Fig. 34) suggests that herbivores used Carex spectabilis communities most frequently. Other communities with moderate to high use included the Phlox—Festuca, Phacelia scree, Phyllodoce, and Cassiope communities. Goat pellet groups were more abundant in areas with high or medium goat density than those with low goat density. Marmot dens occurred most frequently in the Phacelia scree, Phlox—Festuca and the three Carex spectabilis communities (Valeriana, Vaccinium, Lupinus). These five communities have relatively little bedrock at the soil surface.

|

| Fig. 34. Mean number of ungulate pellet groups and marmot dens in plots by community type. |

Grazing Patterns

Determining which herbivore species was responsible for consuming plants was difficult in the absence of direct observations. Evidence of herbivores (i.e., sign) within or in the vicinity of plots where grazing occurred was used to infer the species likely responsible for the grazing, but accuracy was not assured. Hence, results were interpreted conservatively.

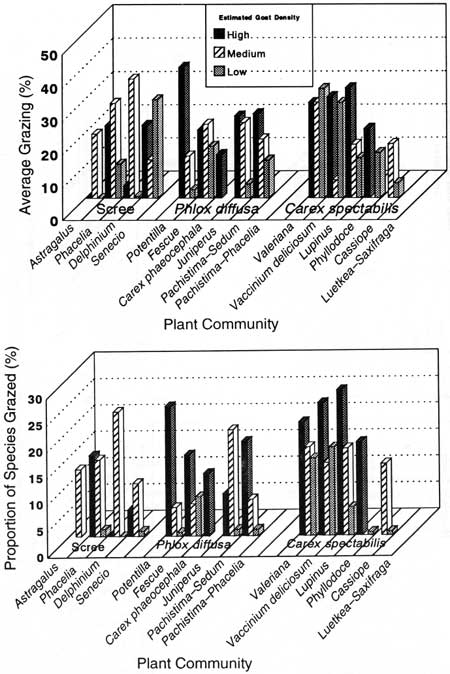

Two measures—percentage of species grazed and average grazing—provided a crude measurement of herbivory by community type and estimated goat density (Fig. 35). The percentage of species grazed was largest in high or medium goat density areas across all 16 community types. This indicated that, for a particular community type, herbivores were less selective when grazing in high or medium density areas compared to low goat density areas. Average grazing generally followed the same pattern except that, in low goat density areas, it was highest in the Senecio and Carex—Valeriana community types.

|

| Fig. 35. Grazing level indicators in high, medium, and low goat density areas by community type; average grazing (top) and proportion of species grazed (bottom). |

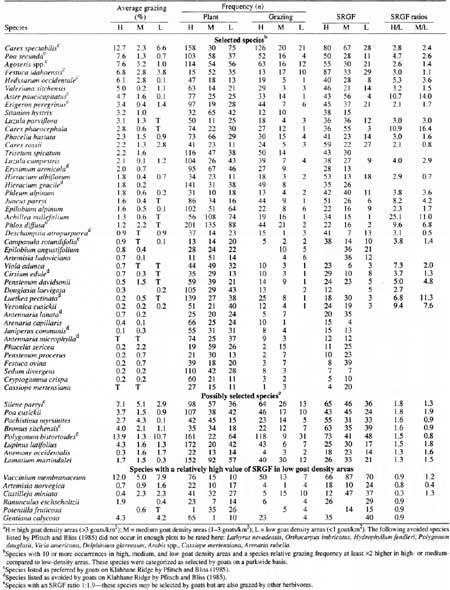

A rough idea of plant species selected by mountain goats on a parkwide basis was obtained by comparing species relative grazing frequency and average grazing of species that occurred in high, medium, and low goat density areas (Table 27). Carex spectabilis, Poa secunda, Agoseris spp., Festuca idahoensis, Hedysarum occidentale, Valeriana sitchensis, and the endemic Aster paucicapitatus had relatively high average grazing in areas with high goat density compared with medium or low goat density areas. Additionally, relative grazing frequency for each of these species in high density areas was at least 2.6 times greater than in low density areas. These same species (except Valeriana sitchensis) were identified as preferred mountain goat forage by Pfitsch and Bliss (1985). Thirty-three species, including rushes, forbs, grasses, sedges, ferns, and one shrub, were grazed more frequently in high density areas compared with low goat density areas.

Table 27. Average grazing plant frequency, grazing frequency, and

species relative grazing frequency (SRGF) for plant species in

mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus) summer range of

Olympic National Park.a

(click on image for a PDF version)

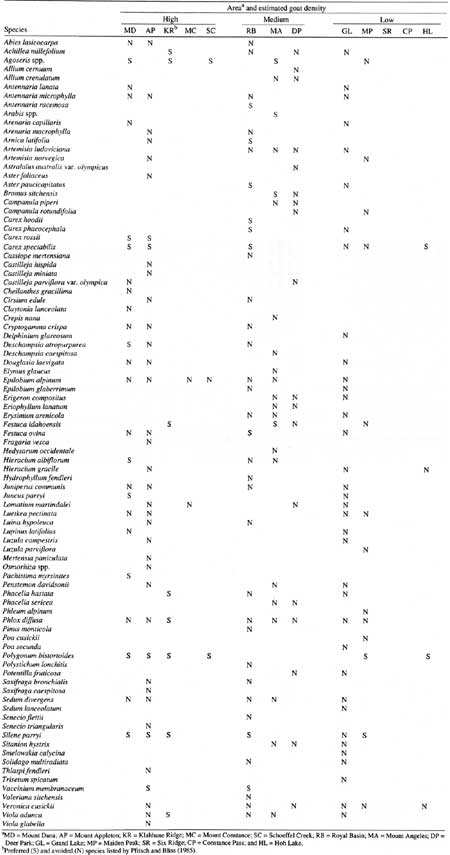

An examination of grazing on individual plant species by area (Table 28) revealed that a species considered selected by goats in one area might be nonselected in another.13 For example, Deschampsia atropurpurea was considered selected forage at Mount Dana and nonselected at Mount Appleton—both areas of high goat density. Additionally, three species (Carex spectabilis, Polygonum bistortoides, and Silene parryi) were selected in one high as well as one low goat density area. We assume these three species were selected also by herbivores other than goats.

13The method used to classify species as selected or nonselected parkwide was based on the relative difference in the value of SRGF in high, medium, and low goat density areas. This criterion (i.e., SRGF in high, medium, and low goat density areas) could not be applied to individual areas because there were no goat density estimates for individual plots. Hence we used the criteria described in Appendix A1 to determine selected and nonselected species (SRGF ≥50, SRGF ≤25) for individual areas (e.g., Mount Dana).

Table 28. Selected (S) and nonselected (N) plant species in high, medium,

and low mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus) density areas of

Olympic National Park.

(click on image for a PDF version)

Interpretation

Several indicators, including pellet groups, tracks, wallow or bedding sites, grazing, and trails, showed that herbivores interacted extensively with vegetation and soil in mountain goat summer range. Mountain goat sign was most prevalent, followed by marmots, deer and unidentified ungulate, and elk. Mountain goats evidently used or at least traveled through every sample area, even those with low goat density. Marmot sign and deer and unidentified ungulate sign occurred in more than half the sample areas—elk sign was encountered infrequently.

The frequency of herbivore sign in the different areas suggested that there was broad overlap among goats, deer, and marmots in goat summer range and that elk utilized somewhat different areas. Field observations indicated that preferred summer range of migratory elk differed from that of goats—elk used meadows and forests associated with subalpine and upper montane cirques rather than the ridge tops and rocky outcrops occupied by mountain goats. Studies of radio-instrumented elk by Schroer (1987) supported this interpretation of their summer distribution.

Substantial soil disturbance by herbivores was documented. Disturbances in low goat density areas were attributed mainly to elk, deer, and marmots. Mountain goat wallow or bed sites occurred mainly in high and medium goat density areas. Even though the precise effects of trampling and wallowing by mountain goats were not quantified, goat activities have undoubtedly increased disturbance levels. Evidence of disturbance by other herbivores was present but inconsequential compared with goat disturbance in most areas where estimated goat density was high or medium. Few studies have been conducted on herbivore use of subalpine and alpine vegetation within the summer range of mountain goats in Olympic National Park. Kuramoto and Bliss (1970) reported that the Olympic marmot made extensive use of mesic grassy communities (Phlox—Festuca); that deer grazed mainly in the mesic grassy, Saussurea forb, and tall sedge (Carex—Lupinus) communities; and that elk were most often observed using the Valeriana forb (Carex—Valeriana) and tall sedge communities. Wood (1973) found that marmot colonies were most often in the Carex spectabilis (Carex—Lupinus), Phlox—Festuca and Carex—Valeriana communities and less often located in sites dominated by Saussurea americana, Carex nigricans, or Phyllodoce empetriformis. Voles (Microtus oregonii) were trapped most frequently in Carex spectabilis meadows and less in Carex—Valeriana and Saussurea forb meadows (Sheehan 1978).

Deer and unidentified ungulate sign occurred most often in the Carex spectabilis (tall sedge, Valeriana forb) communities and in the Phlox—Festuca (mesic grassy) communities. However, the relatively small amount of elk sign encountered above 1,520 m suggests that, at higher elevations at least, elk may use the Phacelia scree, and Phyllodoce (heath shrub) communities in addition to the tall sedge and mesic grassy communities. Our study supports observations by Kurainoto and Bliss (1970) with respect to plant community use by deer and elk.

Marmot dens in mountain goat summer range occurred in relatively few plant community types. Three factors may be important selection criteria for marmots: snow depth, the amount of bedrock, and, tentatively, some minimum level of standing crop in the community. The first factor is proposed because most marmot dens occurred in plant communities containing Carex spectabilis, all of which occurred at the wet, delayed snowmelt end of the community gradient. These observations are similar to those of Wood (1973) and may relate to the observation that marmots perished in their dens overwinter unless there was sufficient snow to provide insulation (Barash 1973). The second factor is proposed because marmot dens were also observed in the relatively early snowmelt Phacelia scree and Phlox—Festuca communities. In both instances, there is little exposed bedrock; den construction would obviously be difficult in sites with abundant bedrock. The possibility that low-standing crop plays a role in marmot selection of den sites is suggested because communities such as the Senecio scree have delayed snowmelt and little bedrock but have low plant cover (i.e., low standing crop). In all likelihood, a combination of these factors influences site selection by marmots.

Mountain goat use of the plant communities seemed to reflect selection for rock outcrops and cliffs rather than for plant species composition. The 16 of 17 plant communities utilized by goats ranged from 7 to 105% plant cover and contained hundreds of plant species, many of which were not shared among community types.

Mountain goats may select certain plant species locally, but there was little consistency among areas; plants selected in one region were not selected in others. This reinforces the interpretation that summer range selection by mountain goats is based more on habitat requirements than on plant communities. Our results were consistent with studies of mountain goats throughout their native range (Casebeer et al. 1950; Brandborg 1955; Adams and Bailey 1983; Campbell and Johnson 1983; Fox et al. 1989) and in the Olympic Mountains (Stevens 1979; Pfitsch and Bliss 1985).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

chap9.htm

Last Updated: 12-Dec-2007