|

GEORGE ROGERS CLARK

Selected Papers From The 1983 And 1984 George Rogers Clark Trans-Appalachian Frontier History Conferences |

|

"Unjust Encroachments:" British and French Territorial Claims in North America to 1763 [1]

Linda Carlson Sharp

Head, Technical Services

Indiana Historical Society Library

In 1650 and 1651, Nicolas Sanson, Geographer to the King of France, published maps of North America and the world, respectively. [2] Sanson, a prolific publisher, may have attached little notice to these maps, but they have acquired great importance in the cartographic history of North America, as they show the five Great Lakes for the first time on a general-purpose map.

It is no surprise that the maps are of French origin. The earliest accounts of the Great Lakes are by French explorers, and Samuel de Champlain's account of 1632 included a map [3] which served as the authority for Jean Boisseau's Description de la Nouvelle France. [4] French interests in the area were strengthened by the presence of the Jesuit Indian missions. [5] Annual accounts of the missions, the Jesuit Relations, provided more detailed information on the region than that reported by the first explorers; Coronelli's strikingly accurate depiction of the five Great Lakes from 1689 draws heavily upon Jesuit narratives and mapping. [6] Sanson's inclusion of the Great Lakes on his maps reflects both his reputation for constant revision to incorporate new information and the enormous popular interest in France in the Jesuits' Canadian missions. [7]

The French also established trading networks into the continent's interior. Contracts between independent traders and voyageurs and the siegneurial companies provided strict controls over territorial areas for exploitation. [8] Voyageurs' knowledge of the area was incorporated into Chatelain's Carte particuliere dufleuve St. Louis, which combined reasonably accurate mapping with a textual outline of the region's natural resources and a breakdown of trade good values and equivalencies. [9]

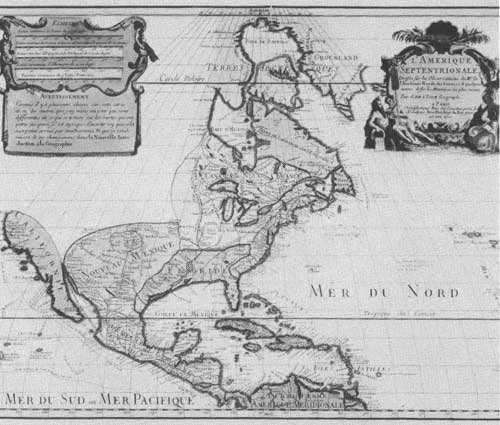

Jesuit proselytizing, trade relations, and physical penetration into the interior, along with established French settlements in the lower Mississippi River Valley, served to assure the French of their domination over the entire valley in the early eighteenth century. [10] Widespread confidence in this assumption prompted Guilleaume de L'Isle to produce his map, L'Amerique septentrionale, in 1700. De L'Isle's graphic representation of extensive French claims to the Mississippi River Valley (Illustration 1) was the first in a series of similar maps to appear. [11]

|

| De L'Isle Amerique Septentrionale, 1700 (Courtesy the Indiana Historical Society.) |

At the same time, English colonial policy dictated the establishment of contiguous colonies along the eastern seaboard. Concern rested with building colonies which were lucrative, well-settled, and easily defended. [12] Whatever official opinion may have been, however, expeditions were undertaken beyond what British policymakers viewed as the natural settlement boundary, the Appalachian Mountains. Robert Beverley's History and present state of Virginia described briefly the explorations of Henry Batts in 1671, across the mountains and over to the Wood River in the Ohio River watershed. Batts proceeded to claim all land between the Wood River and the Mississippi River in the name of the British Crown. The expedition did not receive official notice or backing, and no attempts were made to solidify Batts' claims. [13]

A number of British authors began openly to question the official strategem of colonization. One anonymous writer in 1713 decried the lack of parliamentary response to the French assignment of a trading monopoly in the lower Mississippi Valley to Antoine Crozat. The loss of potential Indian trade and the exclusion of British subjects from the rich available lands, he argued, certainly would prove detrimental to the interests of England's existing colonies. [14] Another writer, in 1720, discussed the danger to colonial defenses should no attempt be made to prevent France from uniting her holdings in the lower Mississippi Valley with those in the Great Lakes area. The establishment of settlements along the Ohio River, he felt, would further British claims to the area and provide some barrier to French domination over the region, which was certain to occur should the British authorities continue to ignore the situation. [15]

Daniel Coxe gave a fuller treatment to these arguments in his Description of the English province of Carolana. He outlined, in some detail, the natural history and resources of the Mississippi Valley and reviewed the various treaties and purchases through which British title to the region might be legally established. He reiterated the importance of the Batts expedition of 1671: if Batts' claims were pursued, the British authorities could legitimately argue precedence over French claims to the area, as French claims were based upon the LaSalle explorations of 1680. [16] A fourth writer, in 1744, discussed the detrimental effects of French occupation on the Indians in "Louisiana," suggesting at the same time that the debilitation brought on by the French might make a takeover relatively simple for a united force of stable, sober British soldiers and colonials. [17]

Whether appeals to popular opinion or French imperialism began to have its effects, British official policy gradually shifted to encourage explorations and to advocate documentation of British claims to the Mississippi Valley and beyond. John Senex's New map of the English empire in America was one of the first English maps to respond to French territorial claims. In it, he extended British colonial boundaries beyond the Appalachians and inset a general view of European colonial holdings in the western hemisphere which limited French holdings to roughly present-day Canada; most of the remainder of North America was allocated to the British. [18] The first large-scale English map of North America, by Henry Popple, followed the same logic. [19]

The British also set up trade relations with the Indians, though in a less structured and less official fashion than those of the French. While French colonies in Canada were set up on a proprietary basis, with trade monopolies granted by and to the colonial authorities, British trade with the Indians was established by independent merchants. For each nation, favorable trade relations with Indian allies was an important part of attempts to check the advances of the other into contested territories. As British interest in the interior grew, trading posts and forts were built further and further from the Alleghenies. The presence of British traders in what the French had come to regard exclusively as their territory was one of the irritants leading to the French and Indian War, the one conflict between France and England which had its origin on the North American continent. [20]

While generalized hostility between the two nations was nothing new, and popular sentiment in each nation in general terms ran high against the other, that sentiment in England found a new outlet with the advent of popular magazines. The first of these, the Gentleman's Magazine, was founded in London in 1731. An eclectic gathering of political and social commentary, scientific and medical reports, and general news, the magazine was widely circulated and quickly imitated. [21] All followed the same general format and were heavily illustrated. News of battles or general articles on a location were often illustrated with maps and fort plans; these were generally specially commissioned and engraved for the magazine in question. Occasionally the maps were inserted without reference to a specific article, but they were more often than not engraved to accompany text. [22]

Some of the best known British cartographers of the eighteenth century got their start by engraving maps for these popular press productions. It is not uncommon to find maps by Thomas Kitchin, Thomas Jefferys, William Seale, and John Gibson in a random search through these publications. News items concerning the colonies might feature natural history, battle plans and fortifications, or epic poetry; a generally heightened awareness of the colonies and the conflicting territorial claims resulted from the wide circulation of these monthly magazines. During periods of open conflict between France and England, intensive descriptions of the separate colonies were published which outlined the strategic military questions for each, as well as its agricultural and mercantilistic importance. [23] An almost-nationalistic fervor was interjected into the magazines, with poetry, prints, and music appearing, all referring to the virtues of British subjects, or the vile nature of the French, and the like. [24]

Following the opening hostilities of the French and Indian War, numerous maps of North America were produced, supporting one side's claim to the disputed territories over the other. Indeed, 1755 is regarded as one of the landmark years in the cartographic history of North America. [25] French cartographers, such as Gilles Robert de Vaugondy and the Sieur Longchamps, conceded the established eastern seaboard colonies to the English. [26] Some English mapmakers were reasonable in their claims as well; Thomas Jefferys, for instance, laid claim to areas for which there were treaties, purchases, and charters. His map, openly based upon the French cartographer D'Anville's large-scale map of eastern North America, also was published in 1755. Jefferys, however, altered the basic boundaries of D'Anville's map in favor of the British claims. [27]

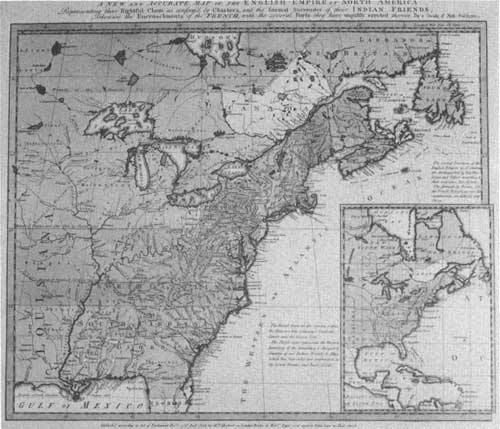

Other English cartographers were less modest in their claims. William Herbert's New and accurate map of the English empire is one of the most graphic representations of a common theme in England (Illustration 2). Openly attributed to a "Society of Anti-Gallicans," Herbert's map allocates only the area around Quebec, Montreal, and Trois Rivieres to the French. The remainder of the North American continent, even without regard to the Mississippi River, was assigned to the British colonies' various jurisdictions. [28] Numerous printed works supported this view, most notably John Huske's The present state of North America. Only Part I of this work, outlining "The discoveries, rights and possessions of Great Britain," was ever published, but that went through two editions within the year 1755. The work was principally extracted and translated from a French text, Histoire et commerce des colonies Angloises by Dumont; it was accompanied by a map engraved by Thomas Kitchin, a virtual duplicate of Herbert's map. [29]

|

| A New and Accurate Map of the English Empire in North America, 1755 (Courtesy the Indiana Historical Society.) |

Publishers were not above practicing deception as well. Jean Palairet's Carte des possessions angolises et francoises du continent de l'Amerique, published in 1755 with an explanatory text, is on first impression an argument in favor of French claims. A careful reading of the text, however, reveals it to be a translation of British ministerial opinion; rendered into French, it was intended for distribution in France with hopes, one suspects, that some few citizens might be dissuaded from French claims. [30]

By far the best-known map from this period is John Mitchell's Map of the British and French dominions in North America. [31] Mitchell, a botanist and physician from Virginia, settled in London and counted numerous influential British nobles as his friends. He had also established friendships in North America with the leading colonial scientists and politicians. His acquaintance with George Dunk, Earl of Halifax, provided him access to the Board of Trade; his familiarity with the colonies ensured the Board's trust in him; and his friendships and continual correspondence with some of the leading citizens of the American colonies made him privy to detailed information concerning the colonies. He became especially interested in some of the intra-colonial boundary squabbles and used his influence with the Board of Trade to gain access to the official surveys, exploration diaries, and cartography associated with the numerous Board-sponsored ventures in the colonies. What resulted from his interest was his great map, published under the auspices of the Board of Trade, which assimilated the most detailed and precise accounts of colonial America, most of which were unpublished, from the Board of Trade archives. [32] While his initial intention was to shed light on the question of accurate boundaries for the individual colonies, the map was quickly seized upon as an authoritative document of all colonial boundaries, including those between the various colonies and the French possessions. Mitchell's map was used as an authority by numerous other cartographers, few of whom acknowledge their debt to him. It was published in four English, two Dutch, three French, and two Italian editions between 1755 and 1791, and remains one of the most impressive cartographical achievements ever. The minute attention to detail, paid to the official surveys, has rendered it useful in this century in inter-state boundary disputes. [33]

Numerous attempts were made at negotiating a settlement to the conflict, which by now had expanded into the Seven Years' War on the European front. Initial negotiations in 1756 failed, and various accounts of the negotiations were published, both in France and in England. [34] There followed public controversies, particularly in England where the points espoused by the ministry were taken up and defended, and just as vigourously denounced. Partisan attacks and defenses were published for popular consumption, in the weekly and monthly papers as well as in pamphlet form. John Shebbeare, a particularly vociferous supporter of the ministerial positions, published a number of pamphlets defending his views and answering others who attacked the ministry. His views were in turn refuted by others. The publishing activity associated with the negotiations verifies the enormous popular interest in the question of equitable settlements to the conflict. [35]

At the same time, a number of authors addressed themselves particularly to the colonies. John Mitchell published, anonymously, a compilation of materials which can be viewed as narrative arguments following from research for his map. His Contest in America between Great Britain and France outlined the importance of maintaining the established colonies, conceded some difficulty in dislodging the French from Canada, and proposed the formation of a "buffer zone" between the two nations' territories, which would have en compassed the Great Lakes region. [36]

Another unidentified anonymous writer proposed methods for uniting the colonies under one or two regional governments dedicated to their common defense. Like Mitchell before him, he was concerned with the almost-intractable colonial governments, some of which refused to defend other colonies for fear that their own commercial or territorial interests might be jeopardized in the process. [37]

Arthur Young reiterated the classic mercantilist colonial view and emphasized the need for defending the colonies to the utmost in order to preserve the basic relationship between them and the Crown. The expense, in his view, would be outweighed by the continued economic benefits derived in England from the continued mercantilist relationship. [38] And, in a final example of the debate, William Smith centered his interest on the pivotal colony of Pennsylvania. Exposed to French depredations and locked into territorial squabbles with New York colony, the colony's ability to survive without aid was called into question; he also cast doubt on the loyalty of the numerous German settlers, characterizing them as Catholic, prone to support the French out of religious sympathy. [39]

Negotiations resumed and failed again in 1761, with similar public debate on all aspects of the negotiations. The French ministerial views presented during the negotiations were translated into English for consumption in Great Britain, [40] while the attendant Remarks upon the Historical memorial published by the court of France explained why the French proposals were clearly unacceptable from the English point of view. [41] One anonymous Letter to a great M[iniste]r, on the prospect of a peace disputed the importance of the proposed acquisition of Canada, advocating instead the English possession of the French West Indies, as products grown there could not be successfully raised in the present colonies and the benefits to Great Britain derived from the islands could not be duplicated in Canada. [42]

When at last the Treaty of Paris of 1763 was signed, [43] the French were excluded from the North American mainland east of the Mississippi River and north of the Great Lakes, to the benefit of Great Britain; Louisiana west of the Mississippi was ceded to England's ally Spain. While the question of French influence and incursions from the north was settled once and for all, there still remained the problem of a foreign power holding contiguous possessions on the continent. British policymakers, and the British public, had been successfully convinced of the importance of the Mississippi Valley to the colonial enterprise. Almost immediately, concerns over the safety and defensibility of the newly acquired western reaches of British holdings were raised, as was the question of the wisdom of the Canadian acquisition, as a potential drain upon limited resources. [44] People and policymakers were at last cognizant of the vast potential of the North American interior and, correspondingly, aware of the problems in administering such a large area. In the end, British resources did prove inadequate to protect the region from molestation. Final allocation of it to the fledgling United States in the Treaty of 1783 was an acknowledgement of the burden placed on the British Crown by attempts to possess it and protect it at the same time.

NOTES

1This paper, with slides, was presented at the first annual George Rogers Clark conference on Trans-Appalachian Frontier History, 1982. Research for this paper was undertaken in part at the Newberry Library, during an NEH-sponsored institute in the history of cartography. Both slides and narrative are based on the collections of the Indiana Historical Society; this is not intended to represent a comprehensive survey of the maps and literature of the period.

2Sanson, Nicolas. Amerique septentrionale (Paris: Sanson, 1650); Mappe-monde (Paris: Sanson, 1651). Cf. R. V. Tooley, Mapping of America (London: Holland Press Cartographica, 1980), passim., for a discussion of Sanson's contributions to seventeenth-century French cartography, and his impact on later cartographers.

3Tooley, R. V. "The mapping of the Great Lakes: a personal view," in Tooley, Mapping of America op. cit., p.p. 305-319, provides an overview of the cartographic evolution of the Great Lakes. Champlain's augmented 1632 version of his Great Lakes map, originally published in 1613, was the first to present the concept of a chain of lakes.

4Boisseau, Jean. Description de la nouvelle France (Paris: Boisseau, 1643).

5A good discussion of Jesuit activity in the Great Lakes region can be found in: Francis Parkman, The Jesuits in North America in the seventeenth century (Boston: Little, Brown, 1883). W. I. Kip's The early Jesuit missions in North America (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1846) compiles unofficial correspondence of the Jesuits. Jesuits first visited the North American continent in 1611; the official Relations began publication in 1632. Cf. James Comly McCoy, Jesuit Relations of Canada, 1632-1673: a bibliography (Paris: A. Rau, 1937).

6Coronelli Vincenza Maria. Partie occidentale du Canada ou de la nouvelle France (Paris: J.-B. Nolin, 1689); this map is based upon "Lac Superieur et autres lieux ou sont les Missions des pères," which appeared in the Jesuit Relations of 1672, compiled by Fr. Claude Dablon. Cf. Tooley, op. cit., p. 313.

7Cf. Parkman, op. cit.

8Biggar, Henry Percival. The early trading companies of New France: a contribution to the history of commerce and discovery in North America (Toronto: University of Toronto Library, 1901). Examples of early trading contracts can be found in manuscript form in many collections; in the Indiana Historical Society, the earliest example of this type of document dates from 1694.

9Chatelain, Henry Abraham. Carte particuliere du fleuve St. Louis (Amsterdam: Chatelain, 1719?). For discussion of trade good values and distribution, see George I. Quimby, Indian culture and European trade goods (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1966), and Arthur Woodward, The denominators of the fur trade: an anthology of writings on the material culture of the fur trade (Pasadena, CA: Socio-Technical Pub., 1970).

10Winsor, Justin. French explorations and settlements in North America, and those of the Portuguese, Dutch, and Swedes (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1884) provides a useful overview of French settlement patterns.

11L'Isle, Guillaume de. L'Amerique septentrionale dressée surles observations de Mrs. de l'Academie des Sciences ... (Paris: de L'Isle, sur Rue des Canettes, 1700). The Indiana Historical Society's copy is one of two known examples of the first state, first edition, of this important North American map. Cf. The Map Collector 26:2-6 (March 1984) and 28:49 (Sept. 1984) concerning this state's unique identifying features.

12Burton, Robert. English empire in North America (London: Nicolas Crouch, 1728). First published in 1685 and updated regularly, this work discussed the English colonial system, with a description of each colony.

13Beverley, Robert. The history and present state of Virginia: in four parts (London: printed for R. Parker, 1705); cited in Edmund and Dorothy Smith Berkeley, Dr. John Mitchell: the man who made the map of North America (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1974).

14Letter to a member of the P----t of G---t B-----n, occasion'd by the priviledge granted by the French king to Mr. Crozat (London: printed for J. Baker, 1713).

15Some considerations on the consequences of the French settling colonies on the Mississippi . . . (London: printed for J. Roberts, 1720).

16Coxe, Daniel. Description of the English province of Carolana (London: printed for B. Cowse, 1722).

17The present state of the country and inhabitants, Europeans, and Indians, of Louisiana . . . (London: printed for J. Millan, 1744).

18Senex, John. A new map of the English empire in America (London: Senex, 1719).

19Popple, Henry. Map of the British empire in America with the French and Spanish settlements adjacent thereto (London: W. H. Toms, engr., 1733).

20Peckham, Howard H. The colonial wars, 1689-1762 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964).

21Carlson, C. Lennart. The first magazine: a history of the Gentleman's Magazine, with an account of Dr. Johnson's editorial activity and of the notice given America in the Magazine (Providence, R.I.: Brown University, 1938).

22Reitan, Earl. "Expanding horizons: maps in the Gentleman's Magazine, 1731-54" (in Imago Mundi, 1984). I wish to express my appreciation to Dr. Reitan for his further review of the topic, "Popular cartography and British imperialism: the Gentleman's Magazine, 1739-1763" (Illinois State University, 1984), which was delivered at the 1984 meetings of the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies.

23Carlson, First magazine, op. cit.

24One need only peruse copies of the various popular magazines for illustrations of this attitude. An example, included in the January 1755 issue of the London Magazine, is entitled "The British Bucks," with "words and music by a True Briton"; it features a florid musical line, and four stanzas of lyric intended to incite a properly martial feeling in all loyal British subjects.

25For an overview of cartographic activity during this time, see Tooley, Mapping of America, op. cit.; an illustrated overview can be found in Seymour I. Schwartz and Ralph E. Ehrenberg, The mapping of America (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1980).

26Robert de Vaugondy, Gilles. Partie de l'Amerique septentrionale (Paris?: s.n., 1755); Sieur Longchamps, Carte des possessions Françoises et Angloises dans le Canada (Paris: Longchamps, 1756).

27Jefferys, Thomas. North America from the French of Mr. D'Anville improved with the back settlements of Virginia and Course of Ohio (London: Jefferys, 1755).

28Herbert, William. New and accurate map of the English empire in North America (London: Herbert & Sayer, 1755).

29Huske, John. The present state of North America, &c. —Part I (London: printed for and sold by R. and J. Dodsley, 1755).

30Palairet, Jean. Carte des possessions angloises et françoises du continent de l'Amerique septentrionale (London: s.n., 1755). The map is accompanied by a 62-p. text, Description abrégée des possessions angloises et francoises du continent septentrional de l'Amerique, pour servir d'explication à la carte publiée sous ce meme titre (London: J. Nourse et al., 1755).

31Mitchell, John. Map of the British and French domimions in North America with the roads, distances, limits and extent of the settlements; humbly inscribed to the Rt. Hon. the Earl of Halifax . . . (London: A. Millar, 1755).

32What concrete evidence there is for Mitchell's early life, and for his later acquaintances and friendships, has been painstakingly gathered and published in Berkeley, Dr. John Mitchell, op. cit.

33A full discussion of the bibliographic history of the Mitchell map, and a summary of its importance to North American cartography, can be found in Walter W. Ristow, ed., A la Carte: selected papers on maps and atlases (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1972). Schwartz and Ehrenberg, Mapping of America, op. cit., also provide a useful discussion of the Mitchell map's place in North American cartographic history.

34Mémoire contenant les precis des faits, avec leurs pièces justficatives (Paris: suivie la copie de l'Imprimerie Royale, 1756) was published by the French government as a justification of the war, and included various documents supporting its contentions; it was published in translation in England under the title A memorial, containing a summary view of facts, with their authorities . . . (London: W. Bizet, 1757; also Philadelphia: printed by James Chattin, 1757).

35For instance, The conduct of the ministry impartially examined: in a letter to the merchants of London (London: printed for S. Bladon, 1756) attacked the British ministry's settlement attempts as particularly injurious to the merchant class of London. This work was soon responded to by Shebbeare's Answer to a pamphlet called, The conduct of the ministry impartially examined (London: printed for M. Cooper, 1756). Shebbeare's series of pamphlets known as "letters to the people of England" defended his views and attacked those with whom he disagreed; these were generally answered by other, unidentified authors, in a lively running interchange.

36Mitchell, John. The contest in America between Great Britain and France, with its consequences and importance . . . (London: printed for A. Millar, 1757). I wish to thank Dr. Bernard Friedman, Department of History, Indiana University-Purdue University-Indianapolis, for his useful summary of Mitchell's publishing activities, "John Mitchell, mapmaker and imperial strategist: looking ahead to our northern boundary" (address delivered at the Indiana Historical Society, 6 November 1983).

37Proposals for uniting the English colonies on the continent of America, so as to enable them to act with force and vigour against their enemies (London: printed for J. Wilkie, 1757).

38Young, Arthur. The theatre of the present war in North America, with candid reflections on the great importance of the war in that part of the world (London: printed for J. Coote, 1758).

39Smith, William. A brief state of the province of Pennsylvania . . . (London: R. Griffiths, 1755).

40historical memorial of the negotiation of France and England . . . (London: D. Wilson, T. Becket and P.A. DeHondt, 1761); translation of Etienne Francois, duc de Choiseul-Stainville, Memoire historique sur la negociation de la France & de l'Angleterre . . . (Paris: Imprimerie royale, 1761).

41Remarks upon the Historical memorial published by the court of France, in a letter to the Earl of Temple (London: printed for G. Woodfall and G. Kearsly, 1761).

42Unprejudiced observer. Letter to a great m--r, on the prospect of a peace: wherein the demolition of the fortifications of Louisbourg is shewn to be absurd, the importance of Canada fully refuted, the proper barrier pointed out in North America, and the reasonableness and necessity of retaining the French sugar islands . . . (London: printed for G. Kearsly, 1761).

43Treaty of Paris (1763). Definitive treaty of peace and friendship between His Britanick Majesty, the most Christian king, and the king of Spain, concluded at Paris, the 10th day of February, 1763 . . . (London: printed by E. Owen and T. Harrison, 1763).

44Whether the Mississippi Valley justified increased settlement activities, as discussed in The expedience of securing our American colonies by settling the country adjoining the River Mississippi, and the country upon the Ohio, considered (Edinburgh: s.n., 1763), or whether such a vast area could be adequately defended, as discussed in Some hints to people in power, on the present melancholy situation of our colonies in North America (London: printed for J. Hinxman, 1763), were questions that were quickly raised. The real costs of defending and administering the newly acquired western reaches of the English empire in North America could hardly be assessed, though some observers predicted that these costs would be enormous. Reflexions sur une question important proposee au public . . . (London: s.n., 1768) continued in this vein, with the wisdom of the Canadian acquisition at the heart of the discussion.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1983-1984/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 23-Mar-2011