|

Volume XXXII-XXXIII - 2001/2002

'Lost' Lost Creek

By Phil Kelley

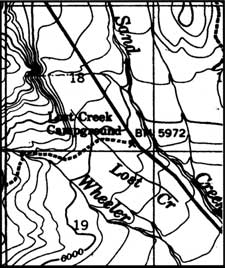

Southeast of Crater Lake, not far above the confluence of Wheeler and

Sand Creeks, is a small stream called Lost Creek (see figure 1). Most

park visitors are unaware of its existence. Those who take note of it

typically do so when stopped at the Lost Creek Campground where they

find the small stream flowing quietly through the woods immediately west

of the camp area.

Lost Creek. Photo courtesy the author.

|

Lost Creek pours full-blown from a spring on the face of a steep

slope about one kilometer northwest of the campground. It flows

unpretentiously through the woods past the campground until the stream

vanishes completely into the porous soils of the area located another

kilometer to the south-southeast of the campground. Over its course Lost

Creek receives no flow from tributary streams, and the fact that it

disappears from view before joining another stream presumably accounts

for the 'Lost' in its name. The spring from which the creek comes serves

as the water source for the Lost Creek campground, and the stream itself

hosts a small population of native bull trout that were introduced in

the late 1990s (visitors should note that fishing in Lost Creek is

prohibited). The banks of the creek, especially in its lower reaches,

display a goodly collection of local wildflowers at appropriate times of

the year.

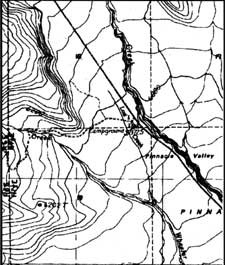

This stream can also be characterized as 'lost' in ways other than

just its hydrographic character. Lost Creek (or at least some stream, if

not the one we see today) appears on early maps of the area. The second

illustration (figure 2) shows the vicinity highlighted on the first

figure as presented on the United States Geological Survey's map of

1911. This map showed the park at a scale of 1:62500, and was based on

plane table surveys in 1908 and 1909. The creek in question is the

diagonal line passing through the large capital 'R' from mid-section 18

through the upper right corner of section 19 and into section 20 to the

lower right. The intermittent stream that goes from west to east through

the text '18', terminating at its presumed confluence with Sand Creek,

should draw a discerning eye. At this point also notice the short creek

paralleling our assumed Lost Creek, from just above the 'er' at the end

of 'Wheeler' down to an intersection with Wheeler Creek. Which of these

three creeks, if any, is really Lost Creek?

Figure 1. Lost Creek in relation to Crater Lake

National Park.

|

The next illustration (figure 3) shows the same area as presented on

the USGS 1:62500 sheet Crater Lake National Park and Vicinity,

Oreg., published in 1956 but based on the same survey as was the

1911 map and augmented by work in 1933. Here the map looks sharper, but

upon close inspection one finds that all that has been added is

typography, roads, and a benchmark; the same three streams we saw in the

1911 information are still there, and the contour lines remain

unchanged.

Figure 4 shows the same area compiled from the USGS's Digital Raster

Graphic (DRG) editions of the 1:24000 quadrangle maps Crater Lake

East and Maklaks Crater. These maps were originally published

and distributed on paper, but the paper and digital editions are

essentially identical; the paper editions were published as Provisional

Edition sheets (whence the crude typography and overlaid symbology) in

1985. Both are derived from aerial photography done in 1981 and 1982,

with field checks conducted the latter year. There is but one creek on

these sheets: the two small ones shown in earlier editions of the maps

(the one in the upper part of section 18 running into Sand Creek and the

one in the east-center of section 19 running into Wheeler Creek) are now

gone. The stream named Lost Creek has been repositioned and is shown

running into Wheeler Creek through the tributary canyon previously

occupied by the smaller unnamed creek. Lost Creek is wandering around in

the woods now, obviously lost.

Park staff conducted field survey work in the Lost Creek vicinity

using high-quality differential global positioning systems techniques

early in the summer of 2000. The work was originally initiated to

clarify the actual position of Lost Creek so that a zone could be

defined around it within which the use of fire-retardant chemicals as a

fire-control measure would be prohibited. This measure is aimed at

protecting the bull trout population in Lost Creek in the event of

wildland fire in the area. We found Lost Creek and some other lost

creeks in conducting this survey.

Figure 5 shows stream structures revealed by the survey. For the

first time we can see what is actually the case in that area: there are

three streams after all, and only one of them (the most southerly of the

original three) is more or less correctly placed. It was shown correctly

on the 1911 and 1956 maps, only to be abandoned on the 1985 versions.

This illustration contains road and contour line data derived from USGS

Digital Line Graph (DLG) data sets, and is information based on the same

surveys used for the 1985 1:24000 quadrangle maps noted above. The

streams from the 1985 sources are shown as dashed lines, and the stream

positions from our field work are shown as bold lines. Lost Creek is

named according to official nomenclature, but we have added unofficial

names for the other two flowing streams in the vicinity: "Hopelessly

Lost Creek" and "Mason's Creek." The latter are strictly local names

bestowed by the surveyor, and are not designations approved by the

National Park Service or the U.S. Board on Geographic Names.

Figure 2: Lost Creek vicinity as depicted on the

USGS map of 1911.

|

Figure 4: Lost Creek vicinity as depicted on the

USGS (Digital Raster Graphics) edition of 1985.

|

Figure 3: Lost Creek vicinity as depicted on the

USGS map of 1956.

|

Figure 5: Shows stream structures revealed by park

staff survey work.

|

It seems that the stream we have called Hopelessly Lost Creek is the

same as the one shown in that location on the 1911 and 1956

publications. Mason's Creek has not previously appeared as an

identifiable stream on any USGS map. Lost Creek is there, all right, but

its upper and lower extremities differ markedly from the information

shown on published maps. The northerly unnamed stream shown first in

1911 is not a part of the complex of creeks in the Lost Creek area. Its

source, as shown in 1911, is actually the source for Lost Creek.1

Results from this latest survey illustrate some of the problems

associated with the making of accurate maps. The surveys of the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the American west were

conducted by real people. They took with them significant quantities of

moderately heavy equipment, and surveying with a plane table and rod

took a lot of time to cover significant areas. Not all areas got

surveyed with equal attention to detail. In this case it seems

reasonable to believe that the survey crew perhaps passed up the north

side of the Wheeler Creek gully, and in so doing, mapped the southerly

small creek with some care. They then went on without looking carefully

for other details. This or another crew might have also passed up the

west side of Sand Creek, and subsequently inferred the details of the

supposed drainage into that gully. None of them explored with care the

interfluve between Wheeler and Sand Creeks, but someone must have passed

through the area and noted the presence of what subsequently came to be

named Lost Creek.

Oddly enough, the ability of surveyors to see small things on the

land diminished considerably as technology evolved. Instead of actually

sending people with mules out to look at the ground, aircraft were used

to photograph the ground from above. To a large degree, the things that

cannot be seen on such photographs are not featured on the resulting

maps. As a case in point, we have three small streams that are not wide

enough to be seen as an open stream on such photographs as were used for

the 1985 maps. These streams are sufficiently narrow that they do not

even create a consistent opening in the vegetative canopy overhead.

Lost Creek is by far the largest (in terms of flow volume) of the

three streams, at least along its upper end. Nevertheless, it has no

significant drainage channel cut down into the landscape downstream of

the uppermost few hundred meters of its course. As a result, there is no

incised channel associated with it (either at actual ground level or

reflected at the top of the vegetative canopy) that might be detected by

the photogrammetric means used to create contour lines from aerial

photography. The vegetative cover associated with the stream banks is

the same as that found away from the streams, and thus there is no

consistent tone or color distinction to be made between the near-stream

vegetation and the surrounding vegetation that might hint at the

presence of a stream. Unlike Lost Creek, however, both Mason's Creek and

Hopelessly Lost Creek do have significantly incised drainage channels

from their heads down to their combined confluence with Wheeler

Creek.

By studying the 1911 map (Figure 2) we see that the channel for

Hopelessly Lost Creek is reflected in the shapes of the contour lines

across which its course passes. The topographic expression of that

channel is much subdued in the 1985 mapping, but it is still there

albeit with no stream. The Mason's Creek channel is not discernable as a

topographic feature on any of the maps.

Prior to our survey, local wisdom in the park seemed to suggest that

Lost Creek was, in fact, connected to Wheeler Creek, and that at times

of high water, it might actually have flowed freely to Wheeler Creek.

There is no evidence on the ground that Lost Creek has had a direct

connection to Mason's Creek, and thus to Wheeler Creek, in historic

time. A superficial Lost Creek channel can be traced for several hundred

meters below the present termination of typical springtime high surface

flow, but this channel wanders down the high ground above Wheeler Creek

by staying essentially parallel to the Wheeler Creek channel axis. The

lack of a previous connection between Lost and Mason's creeks seems

surprising, given that the two come within approximately 50 meters of

one another at their point of closest approach. There is, however,

simply no hint of any cross-connection ever having been present in this

vicinity. Lost Creek appears to have always been perched above Wheeler

Creek, situated there all by itself—and indeed lost.

The dry stream bed of Mason's Creek. Photo courtesy

the author.

What you often see on maps is not necessarily what you will find if

you go there. There are very good reasons why this can be true. The Lost

Creek vicinity at Crater Lake National Park provides a tidy case study

of how and why the differences can occur. There are also other questions

that could be studied here, for those so inclined. One should be why, if

Lost Creek is the largest of the three creeks, is its drainage channel

not incised into the land to any degree? Another relates to why, if

Mason's Creek and Hopelessly Lost Creek have significantly developed

incised channels, do they each have minimal flow—to the point of

being dry over most of their lengths during much of the year? It is also

worth asking why, with its source springs and seeps right next to the

Greyback Road where the old trail to Mason's camp sets off, did Mason's

Creek never appear on published maps?

Notes:

1Our survey did not go north of the Lost Creek springs.

There may well be something draining from further north into Sand Creek

at the confluence location shown.

Phil Kelley formerly taught geography at Mankato State

University, Minnesota, but is currently the Geographic Information

Systems Specialist at Crater Lake National Park.

|