|

SURRENDER ON THE CUMBERLAND

The young soldiers on both sides had now seen the elephant. They had

gained their first real taste of war. Many, like Grant's personal

servant, a broken-English-speaking immigrant named "French John,"

muttered that he now had "no more curiosity; it is satisfied; it is all

gone." The dead, the dying, the cheerless living huddled together

through yet another blustery night beside the Cumberland. Nothing much

had changed about the battle lines. They were where they had been in

the morning, except for Smith's lodgment. More important, the escape

routes on the opposite end of the battlefield remained wide open to the

Confederates although they did not know it.

Indeed, those gray-clad warriors felt betrayed by the sudden change

in fortune. Why had they returned to the entrenchments? Victory had

been theirs, escape so close, so sure. They had not been bested in

battle, merely shuffling back for the

night, content that their leaders would order them out again the next

day and complete the job they had begun. Indeed, Floyd telegraphed

Albert Sidney Johnston about the day's success and issued orders to

begin evacuation at 4:00 A.M. It seemed that at last, someone among the

Confederate generals had given a simple, direct order with a set time

for escape. Floyd also sent scouts to ascertain the exact Federal

positions, and then he called yet another war council.

|

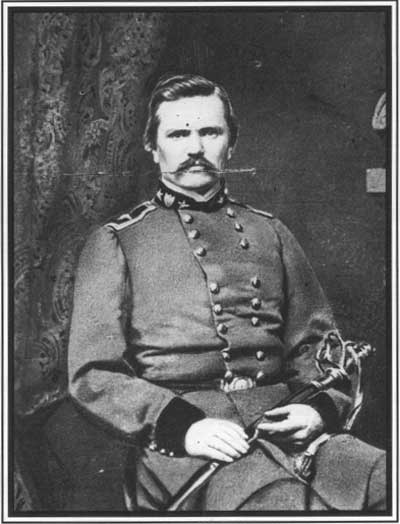

MAJOR GENERAL SIMON BUCKNER (LC)

|

Then, conflicting rumors and reports of renewed enemy activity out on

the perimeter began to filter into Floyd's headquarters. The weary

generals descended into gloom and confusion. Pillow counseled renewed

fighting and holding their position. He did not want to yield a foot of

Tennessee soil. But an increasingly despondent Buckner told of Smith's

breakthrough and an enemy massed to crush his wing of the army on the

morrow. Scouts arrived with word that "the enemy's campfires could be

seen at the same places in front of our left that they had occupied

Friday." Forrest, for one, doubted such reports because his own patrols

earlier had found only stragglers and wounded grouped around those

rekindled fires out on the Forge Road. Yet, other information suggested

that the flooded backwaters of creeks and sloughs would prevent passage

of some escape routes for the army. Floyd's medical director estimated

that only about 25 percent would reach Nashville alive. Frostbite and

pneumonia would claim the rest!

|

ANOTHER VIEW OF THE CAPTURE OF FORT DONELSON SHOWN IN THIS PERIOD

ENGRAVING. (LC)

|

|

CONFEDERATE TROOPS ESCAPE FROM FORT DONELSON. (HW)

|

Because there were not enough river boats or other craft to ferry the

besieged army across the Cumberland (the only two boats available had

earlier carried wounded upriver to Clarksville, returning with a raw

Mississippi regiment as reinforcement), and with all the roads seemingly

blocked or impassable, the situation was grim. The full weakness of a

divided Confederate command surfaced. The scene in the war council now

approached bittersweet comedy, even opéra bouffe. Buckner,

stripped of his usual aggressiveness, perhaps because of fatigue, felt

that further fighting would only waste lives. Floyd agreed with

Bruckner, both generals rationalizing that the army had fulfilled its

mission to buy time for Johnston. Pillow bowed to the pressure,

declaring that "there is only one alternative, that is capitulation,"

but vowing not to be party to it, since he believed that no two

individuals in the Confederacy were more sought by the United States

government for punishment than he and Floyd. True, Floyd was under

indictment for his prewar actions as secretary of war but Pillow's

situation remains unclear. At any rate, Buckner chose to play the

martyr's role, stating it was his duty to remain with his men and share

their fate. Nobody consulted the fourth brigadier, Bushrod Johnson, who

was somewhere out on the defense line, preparing for eventual

evacuation. Nathan Bedford Forrest became so disgusted with the

discussion that he stamped out into the night, proclaiming loudly that

he would take his cavalry out of the trap or die in the attempt!

|

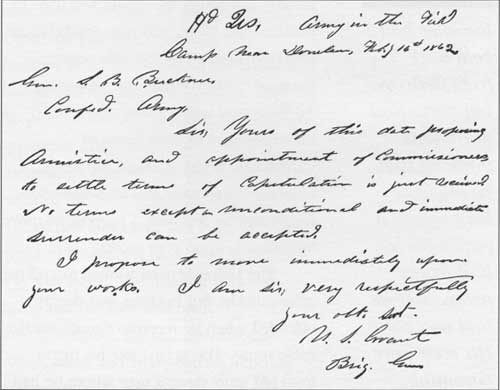

GRANT'S UNCONDITIONAL SURRENDER DISPATCH. (BL)

|

Floyd, Pillow, and Buckner wasted more time trying to decide on

wording for their official reports that might improve their image.

Having satisfied themselves that no moral issues attended their actions,

the generals rapidly passed command from Floyd to Pillow to Buckner. The

Kentuckian granted permission to anyone who wanted to leave the garrison

as long as they did so before he began negotiations with Grant. He then

called for pen, paper, and bugler. Rumors were already spreading among

the soldiers preparing for the evacuation, and the sight of a courier

carrying a white flag headed for Federal lines "caused us to think all

was not well," according to one man in the 3d Tennessee. Lieutenant

Colonel Randall McGavock of the 10th Tennessee was more blunt. Impatient

about events, he "began to smell a rat." So men singly and in pairs

began passing off up the riverbank on their own, trying to escape.

The appearance of other white flags all along the trenches at dawn

caught everyone off guard. Asked by Captain R. L. McClung of the 15th

Arkansas what this meant, one artilleryman shot back: "We are all

surrendered G—d d—m you, that's what it means." Still others

raved and cursed, according to Virginia battery commander John Henry

Guy, while soldiers from the 1st Mississippi openly

wept and officers broke their swords and tossed them away. The majority

just stood around in silent shock. When Major Nathaniel Cheairs (who

was to lead the party to find Grant) questioned the proper bugle call

for parley, a thoroughly irritated Colonel John C. Brown turned to the

regimental band bugler of the 3d Tennessee and told him to blow every

bugle call he knew. "And, if that wouldn't do—to blow his d—n

brains out," he added.

Obviously, tempers were short in Confederate lines that morning.

Once Cheairs's party reached Federal lines, they found the besiegers

preparing for a renewed assault on the works. This was C. F. Smith's

sector, and he vowed to the major that he would make no terms with

Rebels with arms in their hands. His own personal taste was for

unconditional and immediate surrender, suggested Smith. He conveyed both

the Rebels and that sentiment to Grant at the Crisp house headquarters.

Grant, in turn, was somewhat surprised by the sudden turn of

events as well as the snappish rejoinder from his old

mentor. But taking the refrain first used by Foote at Fort Henry and

now Smith before Fort Donelson, Grant formally wrote Bruckner: "Yours of

this date proposing Armistice and appointment of Commissioners to settle

terms of Capitulation is just received. No terms except unconditional

and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately

upon your works."

Bucknner had held back from destroying stores and

munitions, thinking that he might at least secure a parole for

his half-frozen army. Now he had no choice. His men were becoming

unruly.

|

The Union general wanted to end the affair quickly. But Buckner was

deeply offended when he received Grant's uncharitable terms. This

wasn't like his friend from old army days, a man whom he had helped in

deep financial distress at one point. Buckner had held back from

destroying stores and munitions, thinking that he might at least secure

a parole for his half-frozen army. Now he had no choice. His men were

becoming unruly with every passing rumor as "sorrow, humiliation, and

anger" threatened to change a disciplined army into an uncontrollable

mob. The Kentuckian could not delay the inevitable. So he replied somewhat

petulantly that the disposition of the forces under his command

resulting from the change of commanders and Grant's overwhelming superiority of

numbers, "notwithstanding the brilliant success of the Confederate arms

yesterday," dictated that he accept "the ungenerorus and unchivalrous

terms" proposed by the Federal commander.

All the while, those Confederates seeking to escape were doing so.

Forrest rode off with nearly 1,000 cavalry and infantry, successfully

negotiated the reputedly impassable waters of Lick Creek, and

eventually reached Nashville unscathed. Pillow and his personal staff

found a skiff on the riverbank and rowed across the Cumberland and went

overland to Clarksville. Arrival of that Mississippi regiment aboard

the steamboat gave Floyd and most of his Virginia brigade the

opportunity to get out after the unsuspecting newcomers were unceremoniously

dumped ashore to join the rest of Fort Donelson's ill-fated defenders.

They would go into captivity without having so much as fired a volley at

the enemy! Others would escape over the next several days, including

Bushrod Johnson, who slipped past Federal patrols and faded into the

woods after the surrender. Some Confederates were actually carried as

prisoners to St. Louis before they jumped ship and, posing as civilians,

mingled with Federal reinforcements coming back upriver. It has never

been determined exactly how many Confederates ultimately escaped the

disaster. But in all, it was a rather tawdry affair.

|

LED BY LIEUTENANT COLONEL NATHAN BEDFORD FORREST, CONFEDERATE TROOPS

CROSS ICY WATERS IN THE ESCAPE FROM FORT DONELSON. (FW)

|

|

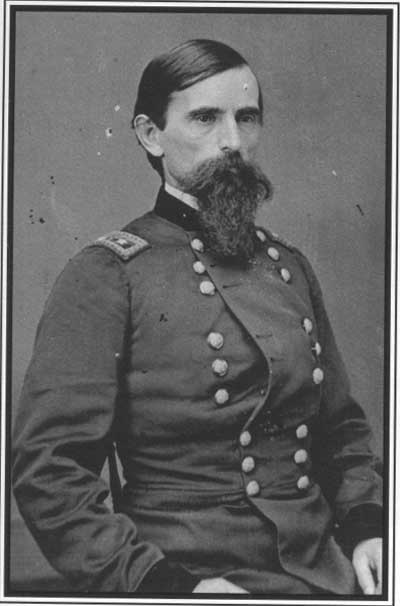

MAJOR GENERAL LEW WALLACE (LC)

|

|

THE DOVER HOTEL (TAVERN) WAS GENERAL BUCKNER'S HEADQUARTERS

AND THE SCENE OF THE SURRENDER. (NPS)

|

Cheairs led Grant and his staff into Dover through lines of sullen,

threatening Confederates. The atmosphere was so tense that Grant's

personal cavalry escort rode with drawn pistols. The party went to the

large double-chimneyed, two-story frame building known locally as the

Dover Hotel at the upper steamboat landing. Here they found Lew Wallace

already present and enjoying a breakfast of cornbread and coffee with

his old friend Buckner. Commander Benjamin F. Dove of the navy had

already been there before being shooed by the army brigadier. Honors

this time would be taken by the army! Grant joined the gathering,

bantering with Buckner about the course of the battle and finding that

the Kentuckian showed little of his pique at the surrender terms.

Buckner apparently chided that had he been in command, Grant would never

have surrounded the fort. Grant chuckled and replied that if Bruckner

had been in command, "I should not have tried in the same way that I

did." The meeting between Grant and Bruckner was brief.

Eventually, the two generals discussed terms and arrangements

affecting prisoner transfer and tabulation of captured stores. When

queried about numbers of Confederates to be surrendered, Buckner

guessed at 12,000 to 15,000 men. The prisoners were to be disarmed and

collected near the upper steamboat landing. They would receive two

days' rations and could keep clothing, blankets, and personal

possessions while the officers could even retain their side arms. As

Buckner rose to leave, Grant told his erstwhile opponent, Buckner, you

are, "I know, separated from your people, and perhaps you need funds; my

purse is at your disposal." The proud

Confederate, unvanquished even at this moment, stiffly declined the

offer. Still, it was a clear indication that the Union general

remembered a similar gesture on Buckner's part from before the war. It

remained a war between gentlemen in February 1862. There was not even

the slightest hint of capital punishment for treason!

|

THIS ILLUSTRATION OF THE FEDERALS MARCH

ON FORT DONELSON APPEARED IN THE MARCH 15, 1862, EDITION OF FRANK

LESLIE'S ILLUSTRATED NEWSPAPER. (FW)

|

Thus, on that fateful Sunday morning, Grant could telegraph Halleck

at St. Louis: "We have taken Fort Donelson and from 12,000 to 15,000 prisoners

including Generals Buckner and Bushrod Johnson, also about 20,000 stand

of arms, 48 pieces of artillery, 17 heavy guns, from 2,000 to 4,000

horses, and large quantities of commissary stores. Hearing cheering

break out among his army, Grant forbade wild celebration. Still,

before long, advancing columns of jubilant Federals moved into the Rebel

works. The dejected Confederates stood around, liberally imbibing from

whiskey and other stores. Then the two sides began a brisk

trade—tobacco, bowie knives and trinkets of the new prisoners being

exchanged for Yankee beef and biscuits. In the end, Mississippian

Selden Spencer penned the appropriate epitaph for the affair. After four

days' hard fighting without rest and exposure to severe weather and

having defeated the enemy in every engagement and signally on Saturday,

he noted in his journal, "with no hope of relief, exhausted, surrounded

by four times our number, cut off from succor, we yielded to fate and were

Prisoners of War."

|

|