|

BACKGROUND TO THE CAMPAIGN

The capture of Forts Henry and Donelson gave Union forces the first

major success toward accomplishment of their grand strategy. This

strategy called for splitting the Confederacy from north to south

via the Mississippi River valley, then turning and splitting it

again from east to west. Confederate authorities countered this strategy

with one of their own—a defense line with strategic strong

points such as earthen forts and water batteries to protect the crucial

waterways. They also concentrated forces to protect major rail lines and

roads entering the frontier of their territory. But lacking resources to

construct a river navy and uncertain of the precise axis of Union

invasion, Southern leaders could only await developments by their

opponents.

The rivers of the antebellum South were the key to unlocking the

Confederate heartland. They served as the great interstate highways of

the period. Railroads were in their infancy, and good roads depended on

weather and local support for their maintenance. Commercial development

of the region required steamboats conveying cotton, tobacco, iron, meat,

and grain to market. In return, these craft carried manufactured

products back to farms and plantations. Rivers and steamboats linked

major cities such as Cincinnati, Louisville, St. Louis, Nashville,

Clarksville, Paducah, Memphis, Vicksburg, Natchez, Baton Rouge, and New

Orleans. The river-steamboat combination also aided the flow of culture and social

intercourse in the hinterland. Yet these strategic assets also held

promise for war as well as peace.

|

A PARTIAL VIEW OF THE WESTERN THEATER. (BL)

|

Confederate political and military leaders at all levels realized

too late that Northern steamboat owners had quickly withdrawn most of

their craft to home ports at the first signs of war. Lost then to the

young Confederacy were vital means for transporting men and materiél and

forming the nucleus of a river defense navy. True, some heavy ordnance

was secured from captured Union arsenals and

navy yards in the South. But generally, while state and local

officials turned to the central government in Richmond for relief.

President Jefferson Davis and his administration countered that it was

mainly the responsibility of western Confederate states themselves to

provide for their common defense. So local manpower fed the newly

formed armies while local industry and farms provided food and equipment

for these troops. Local slave owners supplied the labor for farm and

factory—and to construct the earthworks defending the

rivers.

Tennessee became the Confederate frontier in the West. Memphis

and Nasvhille assumed a role in mobilization, and the state capital

also served as the production and communications nerve center

for the entire region.

|

Tennessee became the Confederate frontier in the West. Memphis and

Nashville assumed a role in mobilization, and the state capital also

served as the production and communications nerve center for the entire

region. Yet frontier defense could be pushed no farther than the

boundary with neutral Kentucky. Indeed, the state's neutrality hampered

Confederate commanders like General Albert Sidney Johnston, sent by

Richmond to defend the vast Department Number 2 of the

Confederacy that included all the area stretching from the mountains

of East Tennessee to present-day Oklahoma. He could not advance his army

to the Ohio River, a natural boundary between North and South, because

of the neutral Bluegrass State. Had he been able to do so, the

Confederacy also could have acquired the agriculturally rich midstate

region of Kentucky as well as iron-rich western barrens between the

Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers, indispensable for fighting a long

war.

|

NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE. IN THE 1860s. (HW)

|

|

BOWLING GREEN, KENTUCKY, IN THE 1860s. (HW)

|

Kentucky's neutrality forced Tennessee governor Isham G. Harris and

his Volunteer State advisers to develop defensive positions even before

Johnston's arrival. Despite topographically superior locations in

Kentucky, Tennessee military leaders chose the locations of Forts Henry

and Donelson solely for political reasons. Hence Fort Henry was sited on

the low eastern bank of the Tennessee River immediately south of the

Kentucky line. Fort Donelson would occupy a better position on a hill

beside the Cumberland near the sleepy Stewart County seat of

Dover—farther inside Tennessee territory. Construction of the forts began in

the summer of 1861, and their locations subsequently locked in both

state and Confederate authorities by default, even when both combatants

consciously violated Kentucky's neutrality early in September.

Confederate authorities eventually advanced their forces to armed

camps at Bowling Green on the Louisville and Nashville Railroad and the

high bluffs above the Mississippi at Columbus, Kentucky. But Forts Henry

and Donelson remained in place, some twelve miles apart and about

seventy-five miles downstream (or northwest) of Nashville. No effort was

made to take advantage of better sites on Kentucky soil along the

rivers. True, both forts screened the lateral rail connection between

Bowling Green and Memphis through Clarksville. In fact, the north-south

railroad and Mississippi River axes of advance soon mesmerized Johnston

and his subordinates to the detriment of concern for the twin rivers

sector. It was left to Tennessee volunteers such as the Nashville-raised

10th Tennessee, the 49th and 50th Tennessee from neighborhoods closer to

the forts, and later the 27th Alabama, reflecting the northern part of

that state's concern for defense of the lower Tennessee River, to

prepare the forts. Eventually some 600 slaves were procured from the

neighborhood to expedite the work. Under Brigadier General Lloyd

Tilghman, a Paducah, Kentucky, native, they literally hacked Forts Henry

and Donelson out of a wilderness.

Fort Henry was of the class known as a full-bastioned earthwork,

standing directly on the bank of the river. It enclosed

about two acres and was named for Gustavus A. Henry, the senior

Confederate senator (styled "the Eagle Orator of Tennessee") and native

of nearby Montgomery County. It mounted seventeen heavy guns, mostly

mounted on seacoast artillery carriages, including one ten-inch

Columbiad, throwing a round shot of 128 pounds in weight and another

ostensibly capable of firing a 60-pound elongated shot. The other guns

included twelve 32-pounders, one 24-pounder rifle, and two 12-pounder

siege guns. Nearly all the guns were pivoted and capable of being turned

in any desired direction although their main strength focused on the

river. Outer entrenchments suitable for infantry were

designed to defend the land approach. The

major drawback was that the fort was located on the floodplain and

could easily be inundated by high water.

|

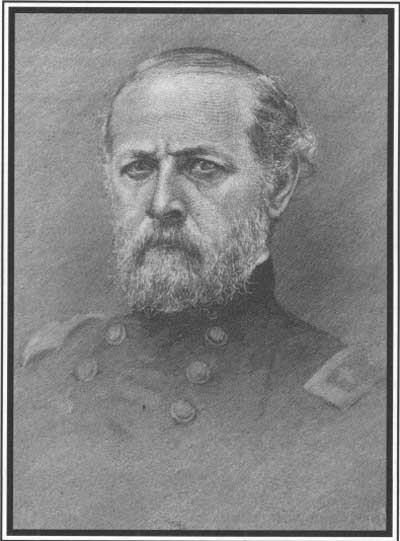

GENERAL LLOYD TILGHMAN (LC)

|

Selected by Colonel Bushrod Johnson, a transplanted Ohioan, West

Pointer, and Nashville professor loyal to his adopted state of Tennessee

as well as the new Confederacy, and affirmed by one of the renowned

engineers of the region, Adna Anderson, Fort Henry's position quickly

became the subject of much derision. In the opinion of another engineer,

Captain J. A. Haydon, and others, on no point on this river "could a

less favorable place have been chosen." Begun about the first of July

1861, Fort Henry was finished in August, and none of the subordinates

such as Haydon felt that they had either rank or prestige to question

the siting decisions of their superiors. Eventually, another fort was

laid out across the Tennessee River on higher ground and named by the

10th Tennessee's soldiers for their beloved commander, Colonel Adolphus

Heiman. Although it was designed to function with Fort Henry, little was

ever accomplished on the site and no guns were ever mounted. Once more,

everyone appeared to believe that there would be plenty of time before

any enemy appeared on the scene.

Fort Donelson, named for senior Tennessee militia general Daniel S.

Donelson, was situated more favorably on the Cumberland. Although

defense of that river also languished because so much attention was

given to Fort Henry's construction, eventually an irregular hilltop

fort was built encompassing one hundred acres overlooking the river near

the tiny Stewart County seat of Dover, about seventy-five miles

downriver from Nashville. At first the Confederates relied on the

reputedly low water in the river and a sunken line of

stone-laden barges across the stream but eventually realized the need

for more substantial shore works. Fort Donelson would become the sole

defense for the state capital.

Two formidable water batteries, situated partway up the slopes of

the one-hundred-foot hill, mounted twelve guns to command the river.

The principal or lower battery boasted one ten-inch Columbiad as well as

thirty-two pounders. The upper battery contained a rifled

sixty-four-pounder Columbiad and two sixty-four-pounder howitzers. All

the guns were protected by thick breastworks surmounted by earth-filled

coffee sacks that also stabilized the gun embrasures. There would be no

question of floodplain or location of this position. Even several small

howitzers situated directly in the main fort could provide plunging fire

on any attacker from the land side. At first, however, there were no

outer infantry entrenchments similar to those at Fort Henry.

Far from the lively atmosphere of the major cities or even towns of

the area, the river fort construction sites were shunned by engineers

and senior officers responsible for their prompt completion. These were

frontier forts, and no socially conscious young scions of Southern

families wanted such an assignment. With winter coming on, the soldiers

slowly built drafty log huts, suffered homesickness as well as the camp

fevers attending field duty, and struggled to drill, mount cannon, and

finish digging the forts' parapets. Overall, the war projected a rather

leisurely air in late 1861 as both sides struggled to organize and train

their fledgling armies. The threat of confrontation seemed distant to

all concerned. Yet in engineer Haydon's words, from the very moment

Tilghman took command, "an energy, confidence and work" took the place

of inactivity, blind faith, and general distaste for effort that had

been infused into the men by lesser officers at the sites. But as Haydon

also noted perceptively, the key to defending the twin river forts in

time of need lay with the accession of forces from Bowling Green and

from Columbus via the railroad, which crossed the Tennessee about twenty

miles above Fort Henry and "inched" up on the Cumberland about fourteen

miles above Fort Donelson.

|

AN ILLUSTRATION OF FORT DONELSON AFTER IT WAS CAPTURED BY

THE UNION ARMY. (HW)

|

|

A LIVING HISTORY DISPLAY AT A FORT DONELSON LOG HUT.

(PHOTO BY JAMES P. BAGSBY)

|

|

THESE KENTUCKIANS, PHOTOGRAPHED IN AUGUST 1860, WOULD LATER BECOME KNOWN

AS THE ORPHAN BRIGADE. (KENTUCKY MILITARY HISTORY MUSEUM)

|

The Confederate story in this period was one of inexperienced yet

patriotic young citizen-soldiers straining to learn the ways of army

life and become a fighting force. Logistical nightmares and strategic

uncertainty, independent state's-rights spirit among western state

politicians, and insufficient men and resources rendered General

Johnston's task very difficult. Physical distances helped negate

coordination along the long defense line. From the Episcopal bishop

turned major general Leonidus Polk commanding at Columbus

on the Mississippi to Major General George B. Crittenden far to the

east in the Kentucky foothills as well as the isolated garrison

commanders on the Tennessee and the Cumberland like Lloyd Tilghman, each

leader acted on his own. Johnston deployed his 55,000 to 60,000 men as

best he could and awaited spring. Making his own headquarters with the

principal maneuver force at Bowling Green (Major General William J.

Hardee's Central Army of Kentucky), the theater commander constantly

telegraphed Richmond for help. Thinking the Louisville and Nashville

Railroad was his most threatened sector, he neglected everything else.

Aides and subordinates occasionally inspected the river forts'

progress, but Johnston never once visited them in person to see their

status or condition.

It is easy to criticize Johnston in retrospect. People expected too

much of him. Jefferson Davis's personal friend (he was the greatest

soldier and ablest man then living, declared the Confederate president),

Johnston too had been born in Kentucky but had adopted Texas as home. A

well-respected senior figure in the old United States Army at the onset

of the Civil War, Johnston had made a well-publicized trek across

country from California to join the

Confederacy only to find that Davis and the War Department proved

more generous with promises and soothing phrases than hard resources

like guns, supplies, and manpower for Department Number 2. Consistently

lacking these war resources Johnston also battled rickety railroads,

cranky states'-rights governors, and an indifferent populace. His major

problem, in the view of postwar observers such as Colonel E. W. Munford,

was simply that he "had no army."

|

GENERAL ALBERT SIDNEY JOHNSTON (LC)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL DON CARLOS BUELL (BL)

|

Yet part of the problem may have been Johnston himself. Johnston was

hamstrung by the traditional military avoidance of campaigning in

winter and his hope of building his own forces for any anticipated Union

onslaught in the spring. His preoccupation with the north-south

railroad line through Bowling Green was questionable because he had

wide-ranging responsibilities elsewhere. Moreover, he lacked personal

knowledge of many of his subordinates charged with defense of the

theater and their individual requirements that might have been better

gained through personal inspection. He acquiesced to Polk's independence

and localized his focus on affairs at Columbus and on the Mississippi.

Johnston sought to coordinate his subordinates via telegraph and

apparently overlooked the fact that steamboats hauling an invasion force

could navigate rivers in midwinter as well as warmer weather and thus

breach his defense line. Perhaps his years in the American West simply

had not prepared him adequately for modern warfare in the geography of

the eastern half of the country.

Meanwhile, in northern Kentucky and across the Ohio River,

Johnston's Union counterparts faced similar problems

and issues.

Northern generals seemed just as overwhelmed by having to organize

large citizen armies, surmount munitions and equipment shortages, and

deal with politicians at the state and national levels. Like the

Confederates, they overestimated the enemy's strength and capabilities.

The administration of President Abraham Lincoln in Washington badgered

them constantly to rescue East

Tennessee Unionists in the mountains. Yet for all those problems,

Federal authorities controlled the upper Mississippi and Ohio Rivers and

could readily secure river and rail transport for military

operations.

The most immediate problems confronting Union generals in the

western theater seemed to be the divided command and how to formulate an

offensive to restore the seceded states to the Union while reopening the

great Mississippi waterway to commerce. Major Generals John C. Fremont

(the great pathbreaking explorer) and his successor, the scholarly Henry

W. Halleck, commanded upward of the 70,000 to 80,000 men from the St.

Louis headquarters of the Department of the Missouri. Major General Don

Carlos Buell commander of the Louisville-based Department of the Ohio,

mustered some 50,000 more. The boundary between their jurisdictions as

it entered Confederate territory was the Cumberland River. Once again,

waterways were all-important.

|

UNION GUNBOATS UNDER CONSTRUCTION AT CARONDELET, ILLINOIS. (BL)

|

Simultaneous river and overland movement by Union armies

offered multiple opportunities to breach Confederate defenses.

|

Offensive operations require more preparations than defending

territory, and so it was in 1861-62. Exploitation of the water

highways provided a major challenge to the Union government.

Simultaneous river and overland movement by Union armies offered

multiple opportunities to breach Confederate defenses. Yet how to

organize the requisite riverine force of gunboats and transports

proved most challenging. Notwithstanding the navy's preference for

war at sea, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles sent officers to the

western rivers to construct and organize a gunboat flotilla. This

"brown-water navy," as it was called, was fundamental to reopening the

Mississippi and its tributaries including the Tennessee and Cumberland.

But it would take months of patient preparation and coordination

between the armed services as well as cooperation with local industries

to produce the requisite force. The army was jealous and distrustful of

intrusion into its affairs and tried to construct its own fleet. But

veteran sailors such as John Rodgers, Andrew Hull Foote, and Henry Walke

persevered. They developed close ties with Halleck and the soldiers and

engaged shipbuilding interests from Cairo, DeKalb, Mound City, and other

river towns to build new or convert available river craft for combat.

Inventor-engineer James B. Fads of St. Louis contracted to fabricate

what would be called the "Western Flotilla" of ironclad gunboats. Army

camps were scoured for gunboat volunteers.

National arsenals dispatched heavy ship board ordnance, and

shore-based service and supply facilities were created to support the

navy on inland waters. All of this preparation took time, however, and

delayed Halleck and Buell from launching their great advance

southward.

The unlikely combination of the obscure Grant and his crusty,

Calvinist sailor counterpart, Foote, brought action to the plans for

this great offensive. Halleck and his subordinates were stymied by the

formidable Confederate bastion at Columbus, which firmly blocked passage

of the Mississippi. Buell and his commanders were overawed by Johnston

and Hardee sitting squarely athwart the Louisville-Nashville rail line

at Bowling Green. A way was needed to overcome both obstacles

expeditiously and economically. Indeed, Halleck, Buell, William T.

Sherman, various Washington armchair strategists, even a woman—the

controversial activist daughter of an old, influential Maryland family,

Anna Ella Carroll, all claimed authorship of what appeared to be the

most viable alternative—the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. One winter evening while

chatting over cigars with Sherman and chief of staff G. W. Cullum in St.

Louis, Halleck supposedly turned to a wall map and circled the

Confederate forts on the Tennessee and Cumberland, "That's the true line

of operations, gentlemen," he said. Random gunboat reconnaissance and

other scouting reports from the area had been suggesting this solution

all fall. Anyone could recognize the weak chinks in Sidney Johnston's

armor by simply looking at such a map, observed Carroll. But looking and

doing something about it were two different matters. The way was

prepared for Foote and Grant.

|

|