|

Lincoln Boyhood

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 2:

The Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial, Phase I

The land acquired, the state began its initial phase of construction. Upon accepting Frederick Law Olmsted's preliminary concept, the Department of Conservation assigned one of its staff landscape architects, Donald B. Johnston, the task of developing Olmsted's concept into a working design. Johnston enthusiastically accepted responsibility for the first phase of landscaping. Johnston's working design was fundamentally based on Olmsted's concept, although Johnston changed the shapes of the plaza and the allee. (See Figure 2—1.)

|

| Figure 2-1: Donald B. Johnston. Planting Plan for Entrance Area of Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial [1927]. Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Papers. Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Indianapolis, Indiana. |

Extending roughly from 1927 to 1938, the first stage involved the removal of several structures from the site of the Thomas Lincoln farm, reforestation of that area, relocation of state Highway 162, grading, construction of the plaza and parking lot, installation of a drainage system and a water reservoir, and the initial planting of the plaza and allee. [1]

Among the Lincoln City structures removed were a restaurant, a garage, a hotel, a school, a church, eleven houses, seven barns, and twenty outbuildings. The ILU bought two acres elsewhere in town which it donated for the construction of a new school building, and financed the construction of the new church. [2]

After removing the structures from the memorial land, the state fenced the memorial park's boundaries, regraded the streets and alleys and the old entrance road, and planted 22,441 native trees and 15,218 native shrubs with the assistance of Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) labor.* (See Figure 2—2.) The "lions and eagles gate" was removed. The gate itself is presently located at the east end of the plaza; the lions, now headless, rest in nearby Lincoln (Buckhorn) Lake, and the fate of the gilded plaster eagles is unknown. [3] The state erected a service building and rehabilitated a remaining house for the park custodian. A small flower garden was planted near the service area (out of public view) to provide flowers for Mrs. Lincoln's grave. [4] Clusters of sycamores, sugar maples, red oaks, tulip poplars, and lindens were planted along the relocated state road, which was routed through the plaza. Red oaks graced the plaza interior, and six hawthorns lined each of the plaza's southern diagonal walls. A semicircle of red cedars lining a curved stone wall (the excedra) marked the center of the southern plaza wall. (The State removed the excedra in 1940 when construction of the memorial building began.) A towering 120-foot tall flagstaff was placed in an island in the center of the plaza. (See Figure 2—3.) Governor Harry G. Leslie presided over the flagstaff's dedication ceremony at the Boonville Press Club's annual picnic on July 12, 1931.

|

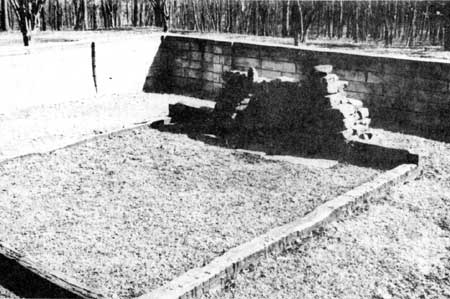

| Figure 2-2: Groundbreaking the plaza area, 1930. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial photograph files, negative no. 7, photographer unknown. |

|

| Figure 2-3: The flagpole and plaza shortly after their construction, 1932. Department of Conservation photo, Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Papers, Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Indianapolis, Indiana. |

*George R. Wilson of the Southwestern [Indiana] Historical Society conducted research to determine what species should be planted. Evansville Courier—Journal, February 2, 1930. Park files, Cemetery History.

Johnston's allee featured a central lawn flanked by gravel walks, their exterior sides each lined with ninety dogwood shrubs spaced four feet apart. Two rows of trees also lined the allee: an inner row of tulip poplars, ten trees per row, spaced thirty feet apart and measuring seventeen feet from the outer edge of the walks; and an outer row of sycamores spaced thirty feet away from the walks, and measuring thirty feet between each tree. Each sycamore was planted at the halfway point between the tulip poplars. Additional sycamores were planted outside the formal rows, making a transition from the formal allee to the restored forest. [5]

By 1932, the Department of Conservation had completed its demolition program and accomplished most of the formal planting. In 1933, the Department budgeted $34,000 for the installation of a water supply system, fabrication of a bronze memorial to be placed at the historic cabin site, and construction of a walking "Trail of Twelve Stones" commemorating various aspects of Abraham Lincoln's life. [6]

The Indiana Lincoln Union began planning the memorial trail in 1931. They intended

. . . to memorialize important episodes in Lincoln's life by the placing of some memento, preferably a stone, along a certain trail where one will be led to appreciate the "stepping stones" in Lincoln's career. [7]

The ILU identified several possible sources for memorial stones, and began collecting them. The stones eventually placed along the one-mile winding trail included (1) a rock from a spring near Abraham Lincoln's birthplace at Hodgenville, Kentucky; (2) a monument erected years earlier by Spencer County to mark the Indiana cabin site; (3) a rock from the Jones store at Jonesboro, Indiana, where Lincoln worked as a clerk; (4) a slab from the foundation of the Western Sun and Commercial Advertiser in Vincennes, Indiana, where Lincoln, on his way to Illinois, first saw a printing press; (5) a foundation stone from the Berry-Lincoln store at New Salem, Illinois, (6) four bricks from Mary Todd Lincoln's Lexington, Kentucky, home; (7) a stone from the White House in Washington, D.C.; (8) a stone from the Anderson cottage at the National Soldiers' Home in Washington, D.C., where Lincoln wrote the Emancipation Proclamation; (9) a boulder from the Gettysburg battlefield; (10) a stone from the old capitol building in Washington, D.C., where Lincoln gave his second inaugural address; (11) a portion of a red sandstone column taken from the porch at the house where Lincoln died; and (12) the Culver stone (discussed earlier), salvaged from the construction of the Lincoln tomb in Springfield, Illinois, and placed at his mother's grave in 1902. Boonville Press Club picnickers were the first to walk the Trail of Twelve Stones in late August 1933. The following year, at the suggestion of Lincoln historian Louis Warren, the Indiana Lincoln Union added descriptive bronze plaques near each of the twelve stones. [8]

Also in 1933, the Department utilized CCC labor to plant 57,000 trees and 3,200 shrubs. [9]* Additionally, CCC labor developed a campground and picnic area, parking, shelters, a caretaker's cottage, roads and trails work, erosion control, and landscaping around the cabin site memorial. (Much of this work was accomplished in what is now Lincoln State Park.) The busy CCC crew also accomplished a boundary survey and a topographical survey of the state lands. [10]**

*Civilian Conservation Corps Camp No. 1543 was stationed at Lincoln City from July 1933 to June 1934. (See Figure 2—4.)

|

| Figure 2-4: Civilian Conservation Corps camp at Lincoln City, 1933. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial photograph files, negative no. 465, photographer unknown. |

Of all the projects undertaken by the Indiana Lincoln Union, the fabrication of the bronze cabin site memorial was fraught with the most problems. Believing it would be inappropriate to construct a replica of the Lincoln cabin, the state hired architect Thomas Hibben, a native of Indiana then working in New York city, to design an appropriate monument to mark the site. The state planned a bronze casting in the shape of the historic cabin sill and hearth, to be surrounded by a stone wall. The area was to be formally landscaped. [11]*

*As stated above, the landscaping was begun in 1933.

The Department of Conservation awarded the bronze casting project to C. W. Hatcher of Indianapolis for $4200; Hatcher subcontracted the project to the International Art Foundries of New York, New York. International Art Foundries, in turn, subcontracted the project to Priessman, Bauer, and Company in Munich, Germany. [12]

In May 1933, the CCC crew located the historic hearthstones, which were situated in a T—configuration and comprised three layers of stones measuring roughly eighteen inches square and five to six inches deep. (See Figure 2—5.) The crew, under the supervision of Horace Weber, excavated the 300 hearthstones without the assistance of heavy equipment in order to protect the stones. The crew then constructed the stone wall around the site and landscaped the grounds (Figure 2—6); this phase of the project was completed by June 1934. [13] The area was ready for the bronze monument. Unfortunately, the bronze monument was not yet cast.

|

| Figure 2-5: Horace Weber, supervisor of the Civilian Conservation Corps crew working at Lincoln City, kneeling over the historic Lincoln cabin hearthstones. The bronze cabin site memorial was placed on the location of the historic stones. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial photograph files, negative no. 13, photographed by O. V. Brown. |

|

| Figure 2-6: Construction of the wall surrounding the cabin site memorial, 1934. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial photograph files, negative no. 31, photographed by Horace Weber. |

For some reason never made clear to the Department of Conservation, Priessman, Bauer, and Company suffered a series of delays in completing the project. In addition to the frustration—plans to dedicate the bronze memorial in the summer of 1934 had to be cancelled because the monument was not ready when expected—the delays caused increased expenses due to devaluation of the dollar. By enlisting the aid of the German consulate and agreeing to extend the initial due date, the Department of Conservation lessened the amount of the added costs. [14] The Department was patient for two years, corresponding with the numerous parties involved, and changing its plans to meet the ever-changing schedule. The situation finally came to a head in May 1935, when the International Art Foundries tried to get more money from the State of Indiana to settle a dispute with the Foundries' subcontractor, Priessman, Bauer and Company. The state responded firmly that there would be no more money for the project, and that the bronze casting was to be delivered to Lincoln City no later than June 15, 1935, or the contract would be terminated, and no additional payments made. [15] The monument was delivered by that date, and was laid in place in July. [16]* Although Indiana Lincoln Union Executive Committee member J. I. Holcomb had advised Governor Paul McNutt to contact President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's office to invite him to dedicate the memorial and view the CCC work in the park, [17] McNutt apparently never acted on Holcomb's suggestion. The final cost of the bronze marker was $5,797.40 in American currency. [18]

*In 1955, Robert D. Starrett of the Department of Conservation authorized the expenditure of $70 for a bronze tablet to replace one which was stolen from the site in 1950. The text read:LINCOLN CABIN SITE

A symbol of the exact size of the Lincoln cabin and the original hearthstones—where as a boy Abraham Lincoln studied by the light of the burning logs.

Indiana Lincoln Union

On the purchase order, Starrett substituted the name of the Indiana Lincoln Union in place of the Indiana Department of Conservation. Statement of account, George J. Mayer Company of Indianapolis, November 16, 1955.

Activity continued in 1937 and 1938. The state purchased the James F. Holstein farm and developed the intersection at Gentryville in accordance with Frederick Law Olmsted's preliminary plan; surveyed and marked the Eli Grigsby farm, and replanted trees which failed to survive the 1937 floods. The state erected signs which had been made by the National Park Service, which supervised the CCC crew at Lincoln State Park. The Indiana Lincoln Union continued to seek funds for the construction of a memorial building. [19]

|

| Figure 2-7: The bronze cabin site memorial. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial photograph files, negative no. 3, photographed by Albert W. Banton, Jr., circa 1968. |

Paul V. Brown accepted a position with the National Park Service, apparently in 1935, as an administrator of Civilian Conservation Corps programs. At first he worked in Indianapolis, later in Omaha, Nebraska. Brown continued as executive secretary of the ILU, even after he left Indiana. The Lincoln park was close to his heart, and his trips "home" frequently included meetings with his friends at the Department of Conservation and sometimes jaunts to the Lincoln park. [20] At Lieber's request, Brown accepted a leave of absence from his National Park Service duties from May 10-31, 1937, so he could write a brief history of the Lincoln park. [21] Noting that Brown's history, while excellent, failed to acknowledge Brown's personal contributions to the effort, Lieber asked the NPS Region II Historian Philip Auchampaugh to review the document. On Lieber's suggestion, Auchampaugh transmitted the draft study to Dr. Louis Warren of the Lincoln National Life Foundation, a noted Lincoln scholar, to revise the study to include a better reflection of Brown's efforts. [22] The ILU published Brown's history, The Indiana Lincoln Memorial in Spencer County, Indiana, in 1938. It contains an excellent summary of the Union's activities in promoting and developing the park through 1937. [23]

Although retired from state government since 1933, Richard Lieber remained active in matters related to the management of state parks and continued to hold a particular interest in the Indiana Lincoln Memorial. He was president of the National Conference on State Parks in 1936; also on its board of directors were C. G. Sauer, who had been involved in the initial planning for the Lincoln park, Conrad Wirth of the National Park Service, and former NPS director Horace Albright. Acting NPS Director Arthur Demaray authorized Service funds to cover Lieber's travel expenses for the 1936 Regional Conference on State Parks. [24]

In 1937 Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes appointed Lieber to the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings and Monuments. [25] In a letter congratulating Lieber on the appointment, Paul Brown observed Lieber's unique opportunity to seek national recognition for the site. [26] "Despite a [National] Park Service opinion that [Abraham] Lincoln was amply represented by the Federal government, and [fear] that a national recognition would lead to similar proposals for sites related to the mothers of other great men," Lieber "led the Board to find the memorial nationally significant in 1939." [27]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

libo/adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 25-Jan-2003