|

Lincoln Boyhood

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 3:

The Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial, Phase II

The recognition of the site's national significance coincided with the transition from the first phase of the memorial's construction, as detailed in Donald B. Johnston's landscaping plans, to the second phase, involving the erection of a memorial building/visitor center and attendant modifications to the landscape.

The Department of Conservation debated over two possible sites for the memorial building for a decade. Donald Johnston's sketches sometimes showed a building at the north end of the allee near the gravesite, and sometimes it was pictured south of the plaza. [1] Finally, in 1938, the Department decided to place the structure south of the plaza, away from the gravesite, so it would not detract from that significant location.

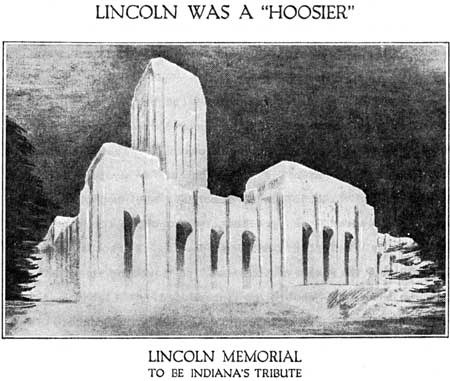

Thomas Hibben, the New York—based architect who designed the bronze cabin site memorial, also prepared preliminary designs for a memorial building under the terms of the original agreement with the Indiana Lincoln Union. [2] In 1930, the ILU issued a second contract for further development of the ideas presented in Hibben's preliminary plans. [3] Hibben's proposed structure included four square courts totalling 200 square feet surrounding a 150-foot tall tower housing a large pipe organ. The courts were to be connected with cloisters decorated with frescoes and sculptures; the tower would be painted with murals. Hibben's design provided for restrooms and even a small restaurant for the convenience of visitors. [4] Newspaper articles about the memorial park frequently included pictures of Hibben's proposal (See Figure 3—1), and it seemed to be well received by the public.

|

| Figure 3-1: Sketch of Thomas Hibben's Proposed Lincoln Memorial. Park Files, Memorial Visitor Center, Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, Lincoln City, Indiana. |

Nevertheless, some members of the Department of Conservation and the Indiana Lincoln Union were uncomfortable with Hibben's design, and correspondence between Colonel Lieber, then chairman of the ILU's Executive Committee, and ILU president J. L. Holcomb, often discussed possible alternatives to Hibben's proposal. [5] This position was most eloquently stated by Lieber, who feared the structure would pose a "monumental imposition" [6] on the humble gravesite. In a letter to Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., he expressed his concerns:

One thing has become clear. The original plan is out. . . . Beautiful as it is, . . . [Hibben's design] still appears much too elaborate and therefore[,] to some of us[,] not at all in harmony with the spiritus loci. [7]

Lieber asked Olmsted to comment on the Hibben plans when they met in Lincoln City to review the first phase of landscaping, which was finally completed. Olmsted agreed with Lieber, and the ILU rejected the Hibben design and ended their contract with him on May 1, 1939. [8]

Ready to commence the second phase of development, the ILU found itself with neither a design for its central element nor an architect to prepare such plans.

Because of his dissatisfaction with the Hibben proposal, Colonel Lieber had contacted a professional acquaintance, National Park Service architect Richard E. "Louie" Bishop in 1937, requesting Bishop's thoughts on a proper memorial expression for the Lincoln memorial. Bishop's response largely reflected the preliminary concept for the park developed by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., a decade earlier, and included the observation that "no towering or otherwise imposing buildings should be introduced." [9] Lieber had his own concept of an appropriate visitor center, and communicated it to Bishop in 1938. At Lieber's request, Bishop prepared an esquisse based on Lieber's description. Bishop sketched a structure showing two square buildings joined by a semicircular cloister, much like the structure which was eventually built, except that the square buildings were set at an angle. [10] This was probably the sketch Lieber included in his July 26, 1938, letter to Olmsted. [11]

Lieber did not contact Bishop again until a year and one-half later. In December 1939, the ILU asked Bishop for suggestions on how to locate an architect for the project. Bishop suggested a competition, but the ILU rejected the idea because of the extra costs and time involved. [12] In a personal letter to Lieber dated December 14, 1939, Bishop asked to be considered for the job. [13] The following day, Paul Brown wrote Lieber and Holcomb a letter commenting on the excellent work Bishop had done for the Park Service, and recommending him for the Lincoln park job. [14] The ILU needed no further persuasion; the Union hired Bishop on January 12, 1940. [15] Citing the opportunity for further cooperation between the Indiana Department of Conservation and the National Park Service, Lieber requested that Region II grant Bishop a six-month leave of absence to work on the project. Lieber hoped the Service would continue to pay Bishop's salary but agreed the ILU would pay it if the NPS could not. [16] Regional Director Thomas J. Allen, Jr., granted Bishop a six-month leave of absence (subsequently extended an additional fourteen months) without salary to work on the project [17]

Bishop clearly understood the qualities Lieber desired in the memorial building. Describing his thoughts on the subject, Bishop wrote:

There should be no false construction or fake design. Materials should be native and largely hand worked. Design should be suggested by the best practice of the days when Nancy Hanks was a young woman. Not a design suggestive of the log cabins she lived in, but of a type of structure that might have been built by one of the best builders of the period, [sic] to commemorate an illustrious pioneer. [18]

Further, Bishop felt his work should "be carefully related to work done previously in an attempt to provide a unified result." [19]*

*Bishop's project notes are located in the Indiana State Library, Indiana Division, Lieber Papers, Box 2, Folders 2-4. These would be particularly useful to future research on the Historic Structure Report for the memorial building.

In an effort to keep the structure simple, Bishop analyzed the functional requirements and identified three basic needs: a central memorial feature, a small hall suitable for public meetings, and a large room with simple facilities for the comfort of visitors. He translated these needs into the three architectural units of the building: the central memorial court, the Abraham Lincoln Hall (suitable for formal gatherings) and the less formal Nancy Hanks Lincoln Hall, which included restroom facilities. [20]

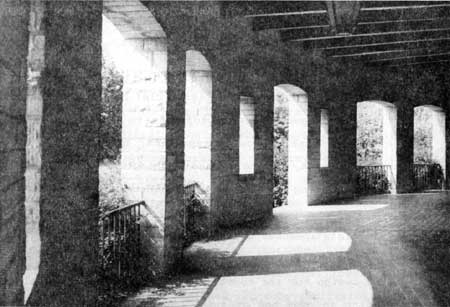

As originally conceived, the Memorial Court was to include a semicircular wall supporting sculptured panels. Bishop was dissatisfied with this concept because he wanted all aspects of the memorial building to be useful as well as decorative. He developed the idea further, and finally decided to make the wall a covered passageway between the two halls (see Figure 3—2), which would prove useful in inclement weather. He designed the cloister to bear five sculptured panels, separated by four large openings. He used straight line segments for these nine elements (five panels and four entryways) rather than a true semicircle, because it was more functional and seemed more appropriate to the rugged pioneer theme. The panels would represent Lincoln's life in Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, and Washington, with the fifth panel representing the deceased president's significance to all Americans. Above the panels and the doorways, passages from Lincoln's speeches would be carved in stone.

|

| Figure 3-2: The cloister joining the Nancy Hanks Lincoln and Abraham Lincoln halls, 1960. Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial photograph files, negative no. 32, photographer unknown. |

The design for the court itself featured a brick walkway surrounding an oval bed of turf. Three stone steps led from the plaza to the walkway; five additional steps led from the walkway into the cloister. Bishop included the steps to ensure the sculptured panels' visibility from the plaza and allee.

Bishop designed the memorial to be made as completely as possible of Indiana materials which would have been available in the early nineteenth century. The exterior walls were to be handcut Indiana limestone, with windows of a size appropriate to the historic period. The roof would be of sheet copper.

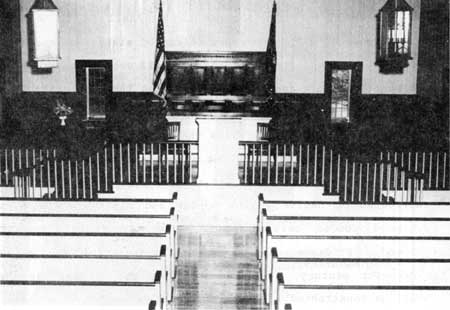

Bishop planned the Abraham Lincoln hall (which he also called "the chapel") to measure thirty by sixty feet and hold about 250 people. Entrances to the small vestibule were from the memorial court and the cloister. The interior walls were to be of St. Meinrad sandstone with a cherry wainscot, except in the rear of the room, where the paneling extended to the ceiling. He designed a rostrum at one end of the room and a balcony at the other; these and the pew-type seats were to be fabricated of native yellow poplar and black cherry. The finished wooden ceiling would leave structural members exposed. Hardware was to be appropriate for the early nineteenth century. (Figure 3—3 shows the Abraham Lincoln hall, as constructed.)

|

| Figure 3-3: The Abraham Lincoln hall, 1965. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, photograph files, negative no. 2, photographer unknown. |

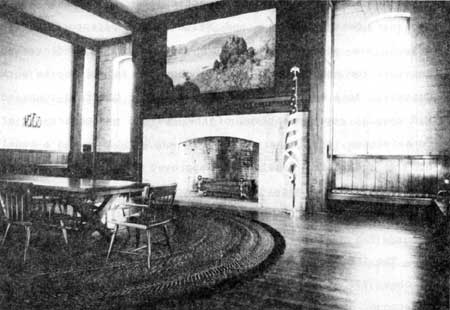

The Nancy Hanks Lincoln hall, also with a small vestibule, featured a thirty by forty-five foot room with a large stone-arched fireplace. The walls would also be of St. Meinrad sandstone; the heavy wood beam ceilings would be plastered. A rear entrance would lead to the restroom facilities and the parking area. (See Figure 3—4.)

|

| Figure 3-4: The Nancy Hanks Lincoln hall, 1964. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, photograph files, negative no. 10, photographed by Robert L. Burns. |

Bishop started work on the design on February 15, 1940. The Indiana Lincoln Union hired Claude Coyne from the Department of Conservation to assist Bishop with the project. Coyne's assistance and the close cooperation of the Department of Conservation, particularly Assistant State Engineer Denzil Doggett and State Parks Director Charles DeTurk, who provided mechanical and structural engineering services for the project, made it possible for Bishop to work quickly. At a meeting attended by Governor Clifford Townsend and several representatives of the ILU and the Department of Conservation, preliminary plans for the building and a model of the sculptured panels were approved without change less than five months after Bishop reported for duty. The ILU approved the construction drawings on October 7, 1940. [21]

The ILU opened the bids for the construction contract on October 30. It awarded the general contract to W. A. Armstrong of Terre Haute and the plumbing and heating contract to Tri-State Plumbing and Heating of Evansville on November 18, 1940. Armstrong's firm broke ground the following December 10. Claude Coyne served as onsite construction supervisor for the project. Bishop visited the project frequently. [22]

Sare Hoadley Stone Company of Bloomington, Indiana, prepared the handcut stone for the structure. The Department of Conservation furnished the native timbers and finish lumber. On his own time and at personal expense, park custodian Walter Ritchie personally scoured southern Indiana to locate timber for the project. The remainder was supplied under a contract with Carnahan Lumber Company of Loogootee, Indiana. Adams Westlake Company of Elkhart Indiana, custom-made the aluminum sash windows for the structure. William Hermann and Son of Indianapolis custom-made the cherry table, chairs and benches and the chapel pews.

The Pierson-Lewis Hardware Company of Indianapolis furnished the hardware, including the custom-designed brass locks for the entrance doors. Leonard Kord of Indianapolis fabricated the bronze grilles and light fixtures, using molds prepared at the State Reformatory at Pendleton, Indiana. The large bronze exterior lanterns were redesigned and rebuilt from fixtures originally designed for use at George Rogers Clark [State] Memorial in Vincennes, Indiana. These exterior fixtures had already been shipped when the War Production Board halted production of the bronze interior lanterns. The Board rejected the state's requests for permission to proceed with the fabrication of the bronze lights, and Kord could not work on them for several months. Frustrated, but not overcome, Bishop studied alternatives for the lanterns and eventually developed a design replacing the bronze frame with cherry wood. Kord completed the interior fixtures according to the revised design.

Using materials supplied by the Seymour, Indiana, Woolen Mills, the Richmond State Hospital at Easthaven, Indiana, fabricated the braided rugs. Seymour Woolen Mills held the United States Government contract for white Navy blankets, and cut excess blankets into two-and-one-half-inch strips, which they then dyed according to specifications for the rugs. Department of Conservation architect Ernest Jackson designed the rugs, the largest measuring twenty-one feet in diameter, two smaller rugs measuring five by eight feet, and four bench pads measuring two feet by seven and one-half feet, under Bishop's supervision. [23]

Integral features of the memorial building were the sculpted panels facing the memorial court. The ILU had hired Indiana sculptor Elmer H. "Dan" Daniels to prepare a model of Bishop's plans for the building to be presented with the drawings at a meeting of the Union. As reported above, the ILU and the Department of Conservation accepted Bishop's design and the sculpted panels concept on June 11, 1940, but the panels had not been designed nor a sculptor selected at that time. The ILU may have chosen Daniels to prepare the model on the strength of a bust of Abraham Lincoln Daniels sculpted in 1939, which the ILU purchased for display in the memorial building. [24] After the ILU approved Bishop's design, Daniels prepared sketch proposals for the five panels, although he was not under contract to do so. Bishop's report on the memorial's construction stated the ILU received the proposals favorably, [25] but correspondence shows at least one significant person, ILU President J. I. Holcomb, did not like Daniels' work and hoped the ILU would hire a nationally-known sculptor for the panels. [26] Lieber disagreed with Holcomb's advice to find a well-known artist for the job, and indicated it would be a perfect project for a talented young artist to make a name for himself. [27] Apparently not wishing to be at odds with Lieber, Holcomb sent a hand-written note to the colonel, inferring his secretary had added the statement criticizing Daniels, and saying he would agree with Lieber's analysis of Daniels' competence. [28] In May 1941 the ILU sought the professional opinion of nationally-known artist Lee Lawrie, who reviewed Daniels' proposals and some samples of his work, and informed the ILU Daniels was quite able to tackle the project. [29] Still, the ILU delayed hiring a sculptor. Bishop's final report on the memorial states a lack of available funds and the unwillingness of any single person to accept responsibility for such an important decision as the probable causes for the added delay.

As time passed, the delay in hiring a sculptor became more and more uncomfortable. Although funding was still not available, by the spring of 1941 the building was growing daily, and several ILU members feared that if the sculpture was not begun soon, that aspect of the memorial might be delayed indefinitely. They worried the sculpture might be finished by someone at a later date who was not sympathetic to the ILU's fifteen-year plans for the memorial, or, worse yet, perhaps it would never be finished.

About this time, Frank N. Wallace replaced Virgil Simmons as acting commissioner of State Parks. Wallace was deeply concerned that the failure to begin work on the sculpture would result in an unfinished memorial. Wallace enlisted Governor Henry F. Schricker's aid, and the governor called for a review of the Department of Conservation's 1940-41 budget. In light of other Conservation projects postponed because of low funding levels, the governor agreed to commit $30,000 acquired from park fees to pay for the sculpture. On the ILU's recommendation, the Department of Conservation hired Elmer H. Daniels as project sculptor at a salary of $12,000 per year for two years. [30] The Department also purchased a $5000 life insurance policy on Daniels from Lincoln National Life Insurance Company at a cost of $46.45 per year. [31] At Holcomb's request, the Department of Conservation also hired Lee Lawrie as a consultant. [32]

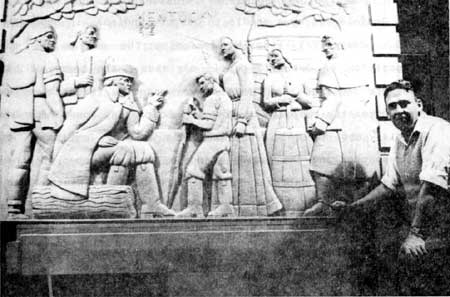

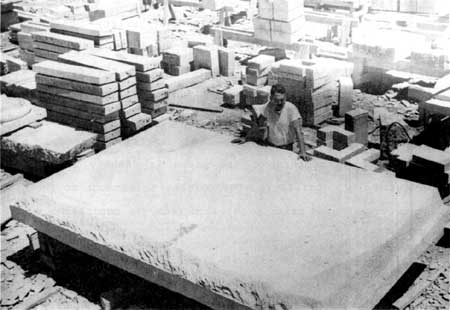

Daniels set up a studio in Jasper, Indiana, in September 1941. His first step in designing the panels was the preparation of detailed pencil sketches. The terms of his contract required that Daniels' work receive frequent review by a committee composed of Governor Schricker, consultant Lee Lawrie, and several representatives of the Department of Conservation and the Indiana Lincoln Union. Lieber obtained permission from National Park Service Director Newton Drury to submit samples of Daniels' work to Ned Burns, Chief of the Service's Museum Division, for comment. At Lawrie's suggestion, Daniels prepared "definitive sketches"—actually sixteen by twenty-seven-inch clay models (see Figure 3—5)—of each panel. The sculpture committee discussed these clay models until they reached agreement on the final appearance of the panels. Then Daniels prepared half-scale clay models of each panel, from which plaster casts were made. The Department of Conservation hired stone carvers to work from the plaster casts; the Department of Conservation subtracted their $65 per week salaries from Daniels' contract. The committee approved the half-scale models in May 1941, and the ten-ton, eight-foot tall by thirteen and one-half-foot wide Indiana limestone panels were completed one year later. [33]

|

| Figure 3-5: Sculptor Elmer H. Daniels posing with his clay model of the Kentucky panel, 1941. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, photograph files, negative no. 4, photographer unknown. |

The committee exercised great care in ensuring the details in the panels were appropriate. For example, they researched carefully and consulted a variety of sources before selecting types of foliage used in the panels. [34] Daniels apparently became frustrated with the committee's watchfulness over minute details which delayed installment payments on his contract. To the Department of Conservation's embarrassment, the artist expressed his frustration to members of the press in January 1942. The following day, Daniels received orders to conduct no further interviews without prior permission from the Department. [35]

Richard Bishop decided early in the design process that the spaces above the panels and cloister entryways must not compete for attention against the sculptured panels. To achieve this goal, and in keeping with his desire to design a simple but elegant memorial structure, he determined that carved quotations, excerpted from Lincoln's addresses, were suitable for this portion of the cloister. Certainly there was a wealth of Lincoln sayings from which to choose. The problem, Bishop discovered, was the selection of nine sayings of approximately equal length to fit in the space available.

|

| Figure 3-6: E. H. Daniels selecting limestone panels at the quarry near Bedford, Indiana. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, photograph files, negative no. 43, photographer unknown. |

Assisted by Indiana State Library Chief Cataloguer Nellie Coats, Bishop compiled a list of potential quotations, all expressing Lincoln's fundamental belief in democratic principles and morality. Colonel Lieber sent copies of the list to Dr. Louis Warren of the Lincoln National Life Foundation and Paul Angle of the Illinois State Library. After a second consultation with Warren and Angle, the ILU selected nine quotations. Bishop then prepared full scale drawings of the quotations which Sare Hoadley used in carving the stone. [36]

Some time later, the National Park Service prepared sheets explaining the panels and summarizing the inscriptions. That information is repeated below:

KENTUCKY PANEL: 1809—1816. The Childhood Years of Lincoln.

The Kentucky panel illustrates the years of Lincoln's life spent on the Sinking Spring and Knob Creek farms. On the far left dressed in the style of the frontier is Jesse LaFollette, grandfather of Wisconsin Senator Robert M. LaFollette and neighbor of the Lincolns at Knob Creek. Beside him stands Thomas Lincoln, father of the President. Seated is Dr. Christopher Columbus Graham, doctor, scientist, and visitor at the Lincoln home. His stories fascinated Abe, who is pictured here at the age of seven. Behind the boy is his mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln. Sarah, his only sister, stands at the churn. On the far right is Caleb Hazel, Lincoln's second schoolteacher.

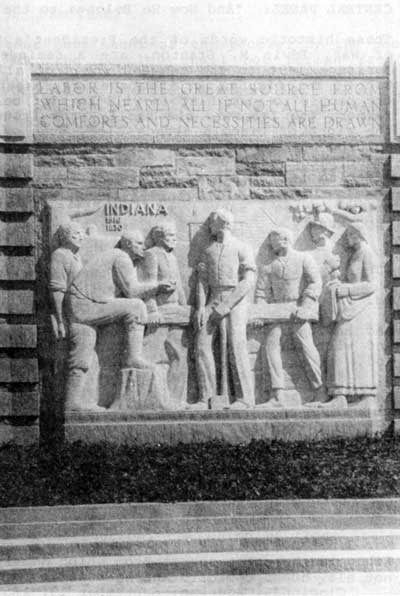

INDIANA PANEL: 1816—1830. The Boyhood Days of Lincoln.

This panel depicts Lincoln as a youth, but fully grown and capable of doing a man's job. At the extreme left is James Gentry, wealthy farmer and merchant. Abe was a frequent visitor in his home. Next to him is Josiah Crawford. Lincoln worked for him three days to pay for a book he borrowed which was damaged by rain. Behind Abe, "The Railsplitter," holding a hewn log are Aaron Grigsby, husband of Lincoln's sister, and Dennis Hanks, his mother's cousin. To the right is James Gentry's son, Allen, who was Lincoln's companion on a trip down the Mississippi River to New Orleans. Beside him is Thomas Lincoln's second wife, Sarah Bush Lincoln.

ILLINOIS PANEL: 1830—1861. The Years of Political Ascendancy.

Here Lincoln is shown receiving congratulations from his friends and associates on his election to the United States House of Representatives in 1846. John Stuart, his first law partner, is on the left. Next is Stephen T. Logan, a later law partner. Grasping Lincoln's hand is his close friend, Joshua Speed, the merchant. Between Lincoln and Speed is William Herndon. To the right and behind the beardless Lincoln sits editor Simon Francis. The woman behind him is Mary Todd Lincoln, and the last figure is Lincoln's friend, Orville H. Browning, who served as United States Senator and in the cabinet of Andrew Johnson as Secretary of the Interior.

WASHINGTON PANEL: 1861—1865. The Years of Command.

In the Washington panel the sculptor has chosen Lincoln's career as Civil War President for his subject. The President is pictured with General Ulysses S. Grant at Grant's headquarters in Petersburg, Virginia, near the close of the war. The other figures are soldiers symbolic of the many brave men who made victory possible.

CENTRAL PANEL: "And Now He Belongs to the Ages."

These historic words of the President's Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, are a reminder of the heritage left to the men and women of all time to come. The figures in the panel represent some of the people to whom Lincoln will forever belong—the farmer, the laborer, the family, the freedman. At the right of Lincoln stands Cleo, Muse of History, holding a scroll on which the deeds of the Emancipator are recorded. Beside her is Columbia offering the wreath of laurel, tribute of a nation to its leader. In the background a cabin and the White House serve as symbols of American opportunity.

[The inscriptions:]

No. 1. A SUPREME BEING

And having thus chosen our course, without guile, and with pure purpose, let us renew our trust in God.

Message to Congress, July 4, 1861.

No. 2. PEACE

To do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations.

Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1865.

No. 3. LABOR

Labor is the great source from which nearly all, if not all, human comforts and necessities are drawn.

Cincinnati Address, September 17, 1859.

No. 4. LIBERTY

Surely each man has as strong a motive now, to preserve our liberties, as each had then, to establish them.

Message to Congress, July 4, 1861.

No. 5. DEMOCRACY

And that government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Gettysburg Address, November 19, 1863.

No. 6. FRIENDSHIP

We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection.

First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861.

No. 7. LAW AND ORDER

It will then have been proved that among free men there can be no successful appeal from the ballot to the bullet.

Letter to James C. Conkling, August 26, 1863.

No. 8. RIGHT AND DUTY

Have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.

Cooper Institute Address, February 27, 1860.

No. 9. THE UNION

I hold that, in contemplation of universal law and of the Constitution, the Union of these States is perpetual.

First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861. [37]

|

| Figure 3-7: The Indiana panel, memorial building. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, photograph files, negative no. 1, photographer and date unknown. |

Plans for the landscaping of the area south of the plaza, including some modifications to the allee and plaza, were accomplished almost simultaneously with the preparation of designs for the memorial building. The Department of Conservation assigned landscape architect Edson L. Nott to the task of preparing this second phase of landscape design for the park. Study of the Nott drawings is somewhat disconcerting, because an analysis of historic photographs and existing conditions verifies only one certainty: no single Nott design (or at least no design uncovered during the course of this research) was fully implemented. Rather, it seems the State of Indiana never selected a single Nott plan for the entire area south of the plaza. Nott proposed a circular walk to surround the flagstaff, which was to be relocated to the hill at the top of the allee; the flagstaff was moved in 1944 (see Figure 3—8),* but the circular walk never was constructed. Nott's designs resulted in the removal of the red cedar excedra, taken out to prepare the area south of the plaza for the court and building; and removal of four large oaks from the plaza, which were cleared to provide an unobstructed view of the building from the allee and plaza. The Department of Conservation moved the stone benches from the cabin site memorial to the corners of the plaza. [38] In accordance with Nott's designs, some of the sugar maples Johnston placed south of the plaza were removed to create an open grassy area behind the cloister, but the remaining trees were Johnston's sugar maples, not the even mix of sugar and red maples Nott proposed. The southern plaza diagonal walls were cut as Nott showed, but existing conditions demonstrate that two hawthorns remained on either side of the cuts, not one on each side as Nott designed.

*The flagstaff was moved up the allee on sets of wheeled axles, as shown in this sketch. Owen Taylor to Don Adams, 1985.

|

| Figure 3-8: The flagstaff and allee, 1973. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, photograph files, negative no. 2, photographed by Richard Frear. |

In the memorial court, Nott's detail planting plan was more carefully followed. The state planted the central oval with grass, and the beds near the cloister with periwinkle. Euonymous flanked the doors of the Nancy Hanks and Abraham Lincoln halls. Historic photographs and the memory of retired maintenance worker Elmer Stein indicate the area immediately in front of the memorial building was once lushly planted, probably in accordance with Nott's detail. [39]

By 1943, the end of construction was in sight. Daniels and his stone carvers completed their work on the panels. The building was nearly finished, as was the landscaping. When the Department of Conservation began construction of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial's final phase in 1940, they planned to dedicate the memorial building as soon as it was completed. [40] On January 24, 1944, however, Department of Conservation Director Hugh Barnhart issued a press release announcing the dedication would be postponed until after the end of the Second World War. [41] There is, however, no record that a dedication ceremony ever took place.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

libo/adhi/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 25-Jan-2003