|

Lincoln Boyhood

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 4:

State Management of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial

The Department of Conservation' s management of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial was fairly simple. The memorial was managed by a custodian who reported to the superintendent of Lincoln State Park.* Architect Richard E. Bishop and Robert D. Starrett, Supervisor of Memorials and Museum Curator for the Department of Conservation, summarized the custodian's duties in a one-page note:

DUTIES

Day-to-day janitor work.

Cleanup courtyard and cloister.

Polishing brass.

Keep rest rooms clean.

Scrubbing limestone floors in lobbies (2 — chapel & hall).

Guide service for public.

- Sell:

Bird Books 10¢

Tree Books 20¢

Memorial Booklet 25¢

Post Cards 5¢ each

Photo Packet 25¢

Map $1.00Turn money & record over

to Superintendent each week

during summer. Cut grass — Courtyard & in front of memorial.

Look after shrubbery as directed by landscape men from central office. Keep limbs and trash out of graveyard.

Keep personal appearance good. Uniform is required.

Ask Kennedy questions and write down information which you could use later.

Call on Superintendent for assistance.

Work Sunday but you get a day off during week in lieu of Sunday. Select day to suit you and Supt. 2 weeks vacation with pay during year. Advise this office a month in advance. Work it out with Supt. Vacation must be taken in calendar year.

VACATION LEAVE IS NOT ACCUMULATIVE. [sic] [1]

*The Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial, consisting of the memorial building, the formally landscaped areas, the cabin site memorial, and the land between the cabin site and the allee, was managed as a subunit of the Lincoln State Park.

Bishop transmitted these directions with some maintenance instructions he had prepared to guide the care of the memorial structure. The guideline addressed care of the building's floor, the various floor surfaces, woodwork, brass and aluminum elements, and other building elements. It also provided instructions for the maintenance of the plumbing and heating systems. [2] A copy of Bishop's maintenance guide is contained in Appendix B.

Grounds maintenance consisted simply of mowing the lawn around the building, allee, and cemetery about once every two weeks. In 1961, the park superintendent instructed the memorial maintenance man to remove the scattered footstones in the small cemetery because they interfered with the mowers. [3] Whether from lack of direction regarding care of plant materials or from lack of time and staff to control the trees and shrubs, by the late 1950s the vegetation in front of the memorial building obscured the main facade of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln and Abraham Lincoln halls.

While funds for maintenance activities were never abundant and the park had to make do with its limited staff, the Department of Conservation accomplished at least one project under contract: the painting of flagstaffs. Tri-State Structural Painting Company of Evansville, Indiana, painted all of the state's flagstaffs in 1953 for a total of $119.70, $70 of which was for materials (probably paint and new ropes). [4] In 1955, contractor K. L. Bains agreed to paint all the Indiana park flagstaffs "for the sum of [$]15.00 Apiece Except the one at Lincoln State Park at Lincoln, Indiana, and that one will be ($45.00) as it is to far away and it's about 125 ft. high [sic]." [5]

Shortly thereafter, Starrett issued a note to Department of Conservation files specifying the use of nylon flags measuring 12— by 18—feet or larger at the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial; he hoped these would whip less in the wind, and thus last longer. Shortly thereafter, Ken R. Cougill, Director of State Parks, notified Bob Starrett that the large flag at the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial was disheveled, and wondered if they should "ask N.P.S. to replace?" [6] (Apparently they frequently made such small requests of the National Park Service.) Several months later, Starrett noted that the National Park Service had sent eight wool flags, and asked Lincoln State Park Superintendent Horace Weber and laborer Elmer Stein to let him know in a year if the wool flags wore better than the nylon. [7]

Although development ceased, for the most part, when the building was completed in 1944, a few changes in furnishings occurred in the decade that followed. In 1945 the park placed Clifton Wheeler's painting of the Ohio River above the fireplace in the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Hall; the Indiana Lincoln Union had commissioned the painting for that purpose. [8] This quiet action gave little indication of the controversy which preceded the ILU's decision to hire Wheeler.

Frank Ball, whose donation of $32,000-worth of land "kicked off" the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial's land acquisition program in 1928, wanted a memorial to his donation placed in the park. ILU President J. I. Holcomb had promised to recognize generous contributions, and Ball hoped to commission a painting of himself presenting the deed for the donated land to Governor Leslie. Ball wanted the painting placed above the fireplace in the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Hall. Holcomb believed his photographic and press coverage of the event had adequately recognized the Ball Brothers' contribution. [9] In a letter to Ball, Holcomb responded:

What we are undertaking at Lincoln City is to be a monument to Abraham Lincoln and his mother. It is not going to be a monument to any other individual, be it architect, sculptor, Governor, or donor. . . [10]

In November 1942, Frances F. Brown, Vice President of the Muncie Art Association, contacted Colonel Lieber to inform him that her organization wanted to donate a mural or painting of Ball presenting the deed to Leslie. Mrs. Brown's letter indicated an artist, Hill Sharp, had already been selected for the job. Bishop and Lieber objected vehemently, and Holcomb concurred. (Sculptor Elmer Daniels supported the idea, and was severely reprimanded for speaking out in contradiction to the "official" opinion of the Indiana Lincoln Union.) On December 30, 1942, Colonel Lieber informed Mrs. Brown of the Indiana Lincoln Union's decision to reject her association's offer. A week later, Ball contacted Lieber, informed him of his disappointment in the ILU's decision, and requested a meeting with the colonel. A series of letters between the two followed, in which each politely argued his position. At one point, Lieber suggested the installation of a drinking fountain, with a plaque dedicating it in thanks to all those who generously donated to the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial. Lieber subsequently dropped this idea. Apparently Lieber never met with Ball to discuss the issue. [11]

Another addition to the furnishings was the acquisition of an organ for the Abraham Lincoln Hall in 1956. This purchase may have been precipitated by a Mrs. Warner's offer to sell her Hammond electric organ, valued at $600, for one-tenth that amount. After careful consideration, the ILU decided to reject Mrs. Warner's offer because the organ was too large for the small hall; it was rather old (built in 1937); it required at least $100 in repairs; and it was not as easy to play as a spinet model. In sum, the ILU felt it was not a good buy. [12]

In the ensuing years, however, they researched various types and brands of organs, and in 1955, they purchased a Hammond church model organ for $2293. The organ was installed on January 27, 1956, and was dedicated in the Lincoln Day ceremony on February 12th. The organ was graced with a plaque stating:

This Organ is a Gift from the Indiana Lincoln Union, who, together with the Conservation Department of the State of Indiana, developed and built the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Sanctuary as a permanent Memorial to Abraham Lincoln and his Mother. [13]

In a handwritten note to Ken Cougill, Bob Starrett inquired as to who would be allowed to take the free lessons which came with the organ purchase; the answer is not recorded. Starrett's note directed that the organ be made available to qualified organists on a "by request" basis, and that students be allowed to use the organ to practice, provided they had a note from their instructors, and the superintendent's permission. [14]

In spite of a February 1952 article featuring "Lincoln Land" in National Geographic, [15] life at the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial remained relatively serene. Use of the Abraham Lincoln hall for formal ceremonies, and use of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln hall for group meetings were the primary functions of the memorial building during the two decades the state managed it. The only recorded attempt at regular interpretation of the Lincolns' life in Indiana occurred in 1959, when the Indiana Lincoln Foundation employed Mrs. Thalia S. Woods, president of the Lincoln Club of Southern Indiana, to present lectures in the Abraham Lincoln hall. For an indefinite period, Mrs. Woods gave four fifteen-minute lectures each Monday through Friday between 10:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. The State also provided her with office space within the building, where she could study and prepare her talks. [16] Mrs. Woods' lectures were apparently the first regular interpretive program at the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial.

Visitor use of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial was, then, generally limited to quiet walks, reflection, and occasional use of the building for meetings or assemblies. There were Lincoln Day activities, usually held in the Abraham Lincoln hall, every year around the twelfth of February, and various historical societies sponsored services at Nancy Hanks Lincoln's gravesite, usually around Mother's Day. More active recreation was pursued in the state park, where fishing, camping, hiking, and other pursuits were common throughout the visitor season. On at least one occasion, however, Lincoln State Park sponsored an activity so large that its overflow onto the usually solemn memorial grounds was inevitable.

In mid-May, 1959, the Spencer County Sesquicentennial Commission, the Indiana Lincoln Sesquicentennial Commission, and the Indiana Lincoln Foundation sponsored a statewide Boy Scout camporall as part of the state's 150th anniversary celebration. In spite of rainy weather, daytime attendance swelled to more than fifty thousand. The two-day event began on Saturday, May 16, with camper registration scheduled from 8:00 a.m. until noon. At 1:30 p.m., visitors joined or watched the Rockport-Lincoln parade, which ended at the Lincoln Pioneer Village, a collection of Lincoln cabin replicas in Rockport, Indiana. Governor Harold W. Handley gave an address at the Pioneer Village at 2:20 p.m., and "distinguished guests" stayed in Rockport for a banquet at 6:00 p.m., while the campers and others returned to Lincoln State Park. The day's events culminated in a campfire program for the scouts and other guests; the program, held on the shore of Lake Lincoln, featured a pageant on the life of the Lincolns in Indiana as well as more traditional campfire entertainment.

Sunday's activities began with nondenominational church services at 9:30 a.m. The "city" of tents was opened for public inspection, allowing visitors to see how well the campers arranged their sites and to watch them prepare their breakfasts. At 11:30 a.m. sponsors invited some of the guests to a banquet at Santa Claus, Indiana. Two hours later, a parade of floats and marching groups traveled from east of Lincoln State Park to a reviewing stand in front of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial. Following the parade, various speakers addressed the gathering. Thereafter, the camporall disbanded. [17]

The sesquicentennial stimulated proposals for changes to the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial. One result was the placement of stone markers at the four corners of the eighty acres Thomas Lincoln owned when he left Indiana in 1830. [18] The state moved an old thirty-foot square auditorium, composed of steel posts on concrete pillars with benches and a roof, once located about forty feet west of the flagstaff (post-1944 position), to the other side of State Highway 162 sometime during the 1950s. [19]

The biggest of the sesquicentennial proposals was the Department of Conservation's plan to build a museum at the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial. The museum would fill a need for exhibit space and would include a library and research room. The Department of Conservation had considered adapting the Nancy Hanks Lincoln hall for this purpose in 1957; that proposal would have placed forty-eight-inch wide cabinets around the perimeter of the room and three table cases in the center. The department scrapped the idea of altering the Nancy Hanks Lincoln hall, however, for lack of the $5000 needed to purchase the cases. [20]

Those who made the decision not to adapt the existing room in 1957 were certainly cognizant that a strong opportunity existed to push for a museum addition as a sesquicentennial project two years later. Indeed, sesquicentennial project planning was already underway throughout the state when the adaptation concept was rejected. The Indiana Lincoln Foundation and the Department of Conservation used the sesquicentennial "fever" to promote the concept of a thirty-six-foot, six-inch by seventy-eight-foot, six-inch structure to be centered on the south side of the cloister. [21] (See Figure 4—1.)

|

| Figure 4-1: Four thousand boy scouts on the allee during the Boy Scout camporall, May 16, 1959. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, photograph files, negative no. 151, photographer unknown. |

The Foundation prepared preliminary sketches of the proposed museum, which they initially hoped could be constructed for $150,000. The Indiana Lincoln Foundation hired architect Edward D. Pierre of Indianapolis to design the museum addition. By that time the estimated cost had risen to more than one-half million dollars. [22] State Auditor Roy T. Combs hoped the project could be funded via schoolchildren's contributions, and issued an open memo "To the Educational Leaders of the State of Indiana" soliciting educators' help in raising funds for the project. [23] The state approved a permit for the project on March 24, 1959; the Conservation Department hoped work could begin later the same year. [24]

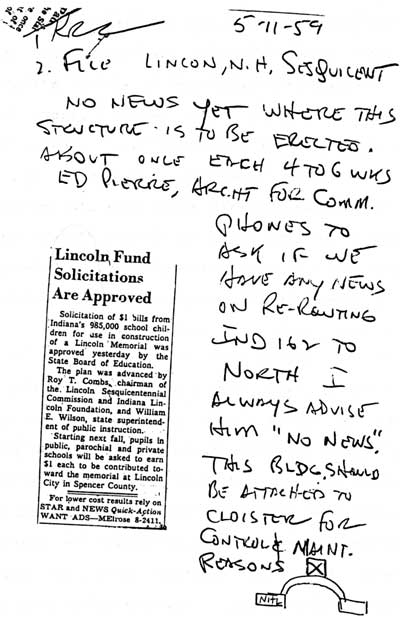

It did not. For reasons not explained in the Department of Conservation's records, the project which seemed so certain in March of 1959 was abandoned less than three months later. Apparently some of the parties involved in the project were equally confused; on June 11, 1959, Department of Conservation Engineer Henry Prange wrote Bob Starrett asking, "What is to be done about this project????????" [25] The following day, Starrett wrote Ken Cougill, recommending that the project be abandoned "in view of the silence 'received' from some quarters." [26]

|

| Figure 4-2: Handwritten note from Robert D. Starret (RDS) to Ken Cougill (KRC) concerning the proposed museum addition. Starrett suggested the building "be attached to the cloister for control and maint[enance] reasons." Park files, Park Proposals: Proposal to Build a Museum onto the Memorial Building, 1959, Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, Lincoln City, Indiana. |

In fact, the handwriting was on the wall weeks before the state's March 24 approval of the addition's building permit. On February 11, 1959, United States Senator Vance Hartke (a Democrat from Evansville, Indiana, who began his first term on January 3, 1959) announced his plans to introduce a bill the following day requiring the Secretary of the Interior to investigate and report to Congress concerning the feasibility of establishing a national monument at Lincoln City. Stating that "the Indiana monument is not an adequate tribute to the Great Emancipator[,]" Hartke introduced S. 1024 on Abraham Lincoln's birthday, as promised, then announced the action at a sesquicentennial celebration. [27] Two weeks later, the Indianapolis Star reported Vice President Richard Nixon and House Speaker Sam Rayburn had been invited to speak at Lincoln State Park, [28] but neither came. On the very day the state approved the building permit for the proposed museum addition, the Evansville Courier ran an editorial favoring national recognition for the Lincoln park. The Courier editorial heralded a flurry of similar articles statewide promoting the concept of national park status for their Lincoln memorial. The editorials cited the appropriateness of national recognition and forecast benefits to state tourism as the reasons all Indianans should support the cause. [29]

If Department of Conservation Engineer Henry Prange and others were surprised by the decision not to spend additional state funds developing Lincoln State Park and its subunit, the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial, they should not have been. Bob Starrett knew the future of state management of the memorial was in question. Starrett's vague reference to others in state government indicates that those in power were prepared to wait and see what results Hartke's study would produce.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

libo/adhi/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 25-Jan-2003