|

Lincoln Boyhood

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 7:

Developing the National Memorial

The transfer of 114.49 acres from the State of Indiana to the United States government in June 1963 effected the establishment of Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial. The land donated by the state was the largest parcel acquired by the National Park Service, and formed the core of the new national memorial. Nevertheless, the National Park Service must acquire several privately—owned tracts in the immediate vicinity and remove the improvements on those tracts to achieve the desired atmosphere at Lincoln Boyhood.

By the time Superintendent Bob Burns transferred to Nez Perce in 1965, the National Park Service owned an additional 14.2 acres. Still, of the total 128.69 acres composing Lincoln Boyhood at that time, only 25 were part of the historic Thomas Lincoln farm. [1] Unfortunately, Burns' purchases utilized most of the $75,000 for land acquisition authorized by the park's authorizing act. While the act permitted a total of 200 acres, the National Park Service could not purchase the remaining authorized 71.85 acres unless Congress raised the land acquisition ceiling. [2] On December 8, 1966, the National Park Service initiated action to obtain the needed increase. One month later, support data for the request was submitted to the Assistant Director for Cooperating Activities, Theodor R. Swem. Finally on April 11, 1972, Congress granted the National Park Service permission to spend an additional $319,286 for land acquisition.

The National Park Service acquired sixteen parcels totalling 10.6 acres in 1973, most of which was needed for development of the living historical farm. [3] By the close of 1976, the National Park Service's holdings in Spencer County were very near the authorized limit of 200 acres. The Service cleared the land of improvements and had a tree planting crew temporarily assigned to the memorial in 1977. By the end of that year, the area finally achieved the predominantly natural atmosphere the Park Service desired. [4]

Although some individuals had problems over the sale of their land as detailed in the Summary of Land Acquisition (see Appendix C), land acquisition at Lincoln Boyhood generally went smoothly. Superintendent Al Banton felt that some landowners demanded more than their land was worth, [5] but records indicate the National Park Service obtained most properties at slightly below their appraised values. [6] Land acquisition at Lincoln Boyhood did not create widespread antagonism toward the National Park Service, as it has in other areas. Most of those whose homes the Service purchased moved to other locations within Carter Township. [7] The community graciously accepted the Park Service's presence in its midst.

Most of the physical development of Lincoln Boyhood occurred under the supervision of the first two superintendents, Bob Burns and Al Banton. In addition to his involvement with the first phase of land acquisition, Burns oversaw the relocation of State Highway 162, the construction of water and sewage systems, and the selection of a location and design for the memorial's visitor center. Banton supervised the construction of the visitor center, two residences, and the maintenance facility, and developed one of the park's most popular interpretive facilities, the living historical farm.

During the decades the Indiana Department of Conservation managed the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial, Highway 162 routed traffic directly into and through the plaza immediately north of the memorial building. Although there is no record of major problems resulting from this arrangement, by around 1960 the state identified the situation as a potential hazard to pedestrians leaving their cars parked in the plaza lot. [8] As part of the discussion of the transfer of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial to the National Park Service, the Service agreed to finance the relocation of Highway 162 to a location north of the memorial building, where Lincoln Boyhood and Lincoln State Park met. The work was accomplished at a cost of $142,214 in 1964. [9] To screen the road from the rear of the memorial building, Burns planted red buds, dogwoods, and tulip poplars along its length. [10]

|

| Figure 7-1: An aerial photograph of Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, circa 1962. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial photograph files, negative no. 9, photographer unknown. |

Burns also oversaw the construction of a residential road and a utilities and a water/sewage system in 1964, and construction of a water reservoir in the state park providing water for both Lincoln State Park and Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial in 1965. The total cost of these projects was $56,300. [11]

Bob Burns' proudest accomplishment was the selection of the site and design of the visitor center. The issue was one of few really controversial decisions in the memorial's history, and continued a debate which originated in the 1920s, when the State of Indiana selected its site for the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial building. As discussed earlier, designs for the state memorial wavered between a gravesite location and the selected location immediately south of the plaza. The debate recurred in 1964 when, in agreement with the Lincoln Boyhood draft Master Plan, the National Park Service's Eastern Office of Design and Construction (EODC) proposed a separate visitor center facility to be built near the Nancy Hanks Lincoln grave. Burns aggressively opposed the EODC proposal, arguing that Thomas Lincoln had buried his wife in the wilderness, and that the wilderness setting should be preserved. He pointed out that the change was an unnecessary contradiction to the Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., plan for the area. He also feared the separate visitor center facility would compete with the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial building for attention, and would stretch his tiny staff beyond its capabilities to serve the public. Northeast Regional Director Lemuel A. Garrison agreed with Burns' assessment of the situation (which was largely reflective of the arguments used in the selection of the site for the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial decades earlier). [12]

The National Park Service decided to adapt the existing memorial building to meet the needs (100—seat auditorium, lobby, exhibit space and restrooms) identified in the Lincoln Boyhood draft Master Plan. The addition would be "complimentary [sic] to the unique workmanship of the original structure" and "leave the basic appearance of the original Memorial Building unaltered." [13] To accomplish these objectives, the Service designed an addition which enclosed the cloister into a lobby area with a visitor contact desk and sales area and some interpretive space. The design showed an auditorium, office space, a library, and storage room added to the rear of the cloister. Additional restrooms and a public telephone were added for the convenience of visitors. A new central heating and air conditioning unit completed the changes to the building. Materials would match those used in the original structure. [14]

The construction package included two residences, a utility building and service area, an exhibit shelter close to the historic farmsite, a small parking lot near the exhibit shelter, and temporary entrance and site location signs. [15] The initial bids for the package came in considerably over the amount available, and the Service considered frame construction for the residences rather than stone houses (as designed) to match the memorial building. Congressman Winfield Denton, member of the House Appropriations committee, instructed the National Park Service to build them with St. Meinrad sandstone, and promised the money would be available. [16] Denton was as good as his word. Rev. Peter Behrman, O.S.B., and Rev. Tobias Colgan, O.S.B. later informed the park that they bid extremely low on the cost of the stone because they were determined that the addition and other structures be built of the local stone. [17]

One of the ideas Burns proposed in his discussions of the visitor center addition design was the replacement of the brick walks in the memorial court (immediately in front of the building) with stone walks to match the building itself. Freeze/thaw action caused the bricks to split and crack, making the walks unsightly and unsafe. Burns contacted Richard Bishop, architect of the original Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial building; Bishop fully supported the change. [18] The Eastern Office of Design and Construction rejected Burns suggestion, but later implemented it. The visitor center, when finished, looked largely as Burns proposed it should.

Superintendent Albert Banton oversaw the implementation of Burns' visitor center vision. Deig Brothers construction company was general contractor for the work; Chester Deutsch and Julian Cornwall supervised the construction of the visitor center addition. [19] Construction went smoothly, and the Deig Brothers firm completed the project on schedule. The addition was dedicated in 1966. [20] (See Figure 7—2.)

On August 8, 1966, Morrell—Felin Co. of Philadelphia loaned a series of twelve Lincoln paintings done by Isa Barnett to Lincoln Boyhood for the dedication ceremony. Apparently, there was some misunderstanding over the term of the loan, for the National Park Service failed to return them until 1970. Copies were made for permanent exhibit in the visitor center lobby. [21] In 1970, Banton ordered rugs from Richmond State Hospital in Richmond, Indiana; the original five'— by eight—foot handwoven rugs made in 1943 were extremely worn and ready for replacement. [22]

|

| Figure 7-2: The ribbon—cutting ceremony at the dedication of the visitor center addition, August 21, 1966. Standing left to right are Northeast Regional Director Lemuel Garrison, Congressman Winfield Denton, Senator Vance Hartke, Birch Bayh, Sr., Lincoln Boyhood Superintendent Albert Banton, Jr., and National Park Service Director George Hartzog, Jr. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial photograph files, negative no. 20, photographer unknown. |

The National Park Service hoped to obtain the extensive collection of Lincoln materials from a local collector, O. V. ("Orrie") Brown, but was unable to negotiate an agreement for the donation of the entire collection because Brown wanted the collection to be exhibited in his home township, Carter Township. In fact, at a meeting at his home, Brown suggested to Superintendent Banton and Assistant Regional Director Palmer that the National Park Service acquire his home and display the collection there intact. Because the Brown home was outside the park boundary, such action would have required an Act of Congress, and was not seriously considered. [23]

Only a portion of the memorial is located in Carter Township: the cabin site memorial and the actual Lincoln farm. To meet Brown's request without changing the park boundary and purchasing the residence would have required the removal of the bronze cabin site memorial and construction of an exhibit facility on the approximate location of the historic Lincoln farmstead. The National Park Service was unwilling to take such action.

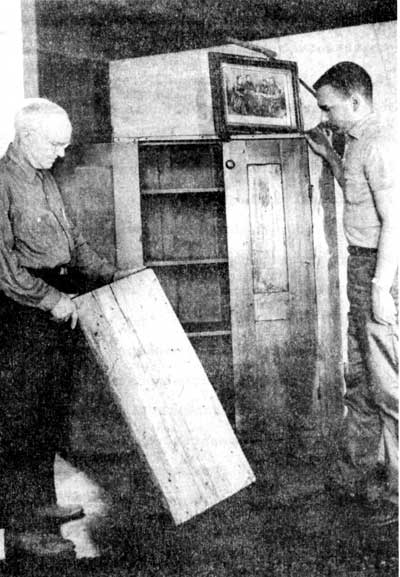

In 1965 Brown donated part of his collection to Lincoln Boyhood (see Figure 7—3); the Service acquired a few other objects after his death shortly thereafter. [24] Although the National Park Service was unfortunate in its inability to obtain the entire O. V. Brown collection, the portion the Service acquired formed the heart of its museum collection during the early years.

|

| Figure 7-3: O. V. Brown and National Park Service historian John Santosuosso looking over a Lincoln. National Park Service photograph files, negative no. 41, photographer unknown. |

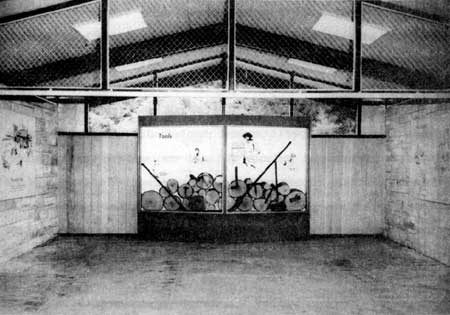

The decision to provide for visitors' needs by adding to the existing Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial included the construction of an exhibit shelter (Figure 7—4) near the historic farmsite. When commenting on the initial design for the shelter, Superintendent Banton noted he liked the layout, but was concerned it would not provide enough light to enable visitors to enjoy the exhibits. In response, the design was revised to include skylights, which proved quite effective in eliminating the potential problem Banton anticipated. [25] In 1966, Washington office historian Roy E. Appleman visited the park, and observed that the exhibits there did little to help visitors understand the Lincolns' life in Indiana. Superintendent Banton ordered two new panels for the shelter, one with a portrayal of virgin Indiana forest, and one showing the Lincolns clearing the land. [26] The shelter exhibits were revised again in 1970, when an artist used Historian Edwin C. Bearss' Historical Base Map as the basis for a presentation of the Pigeon Creek community. [27]

|

| Figure 7-4: The exhibit shelter, circa 1966. National Park Service photograph files, negative no. 4, photographer unknown. |

While Al Banton very effectively oversaw the fulfillment of development designed during Burns' tenure as superintendent, his favorite project was the creation of Lincoln Boyhood's living historical farm Historian Roy Appleman informed Superintendent Banton of Marion Clawson's (Foundation Resources for the Future) concept of a nationwide series of living historical farms representing a variety of regions and time periods. National Park Service Director George Hartzog liked the idea, and had ordered Appleman to investigate the suitability of living historical farms at Lincoln Boyhood and at George Washington Birthplace, Virginia. [28] Represented by Historian Appleman, the Service was working with the Department of Agriculture and the Smithsonian Institution in a joint venture to establish a system of farms in accordance with Clawson's concept. [29] Banton wanted to build a cabin near the historic farmsite to give visitors something to see when they walked the trail past the cemetery toward the historic farm, and was no doubt very pleased that his longtime friend, Hartzog, shared his enthusiasm. In November of 1966, Hartzog's office instructed Banton to take action "as soon as possible to plan a development . . . of that part of the Park which incorporates the original Thomas Lincoln farm as a period farm of the 1816—1830[s]." [30] When Director Hartzog, Regional Director Lemuel Garrison, and Associate Regional Director George Palmer visited Lincoln Boyhood in 1967, Banton suggested building a living historical farm near the location of Lincoln's farmstead. He estimated the cost of the project at $10,000. [31] Although Hartzog made no commitment during his visit,* Banton's timing was right. By this time, Director Hartzog was hoping to develop living historical farms in National Park Service areas before the Smithsonian Institution could initiate a similar program; he feared the Smithsonian would take the lead in historical environmental education. [32] In 1967, Hartzog actively supported living history developments at George Washington Birthplace and Booker T. Washington National Monument, Virginia, and Hartzog had no problem promoting a living historical farm at Lincoln Boyhood.

*While Director Hartzog made no commitment to Superintendent Banton during the visit, while en route to the airport at Evansville he informed Regional Director Garrison and Assistant Regional Director Palmer that he would see that his office approved the project. Palmer recalled no opposition to the living historical farm on the regional level; he said the resistance to the concept was in the Washington office. See George A. Palmer to author, May 22, 1987.

Banton continued to discuss the idea with staff of the Northeast Regional Office. Apparently, the regional office considered two options: a living historical farm "oriented to the bronze foundation" as a symbol of the 1817 foundation; or a "period" farm based on the report Historian Ed Bearss prepared at Hartzog's request. [33] House Appropriations Committee member Winfield Denton supported a living historical farm for Lincoln Boyhood, believing it would attract tourism. Finally, in early 1968, Banton got his long—awaited call from Associate Regional Director Palmer. "'You've got the money,'" Palmer told Banton. "'Go!!'" [34]*

*For additional information about living history in the National Park Service, see Barry Mackintosh, Interpretation in the National Park Service: A Historical Perspective (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, History Division, 1986), 54—67.

Robert (Bob) Utley, Assistant Director for Park Historic Preservation, noted some restrictions on the project based on Park Service policies. He observed that the demolition of the wall surrounding the cabin site memorial and the relocation of the Trail of Twelve Stones would have a negative impact on Lincoln Boyhood's historic resources, and could not be undertaken. He also warned against the reconstruction of the springhouse, which would violate policies governing reconstructions. He admonished that the farm must be considered an "interpretive development" and reminded those involved that the memorial's primary resources remained the site and the memorial structures. [35] Regional Director Lemuel Garrison agreed to limit the project to the portion of the historic farm north of Highway 345, and not to remove the cabin site memorial. [36] Generally, Banton had no problem with these restrictions.* He intended the farm as a device through which farms like Thomas Lincoln's (and not Lincoln's, specifically) would be interpreted. [37]

*There was one restriction Banton ignored. Believing six of the stones in the Trail of Twelve Stones interfered with the farm, Banton ordered them moved from the north to the south side of the railroad tracks in 1967. Superintendent Norm Hellmers had them moved back to their historic locations in 1986. See note to files, Don F. Adams, Interview with Elmer Stein, March 22, 1985.

The site of the living historical farm was tested for archeological material, but no remnants of the historic farm were located. This was not surprising, since four feet of grading occurred when the state installed the bronze memorial. [38] Ground clearing for the farm began on February 25, 1968, and the buildings and fences were standing on the site by the end of April. [39]

In a discussion with Superintendent Banton and Director Hartzog about appropriate materials for the farm's construction, Assistant Regional Director George Palmer insisted that local logs be used. Elsewhere in Northeast Region parks, "period" log cabins built of new logs had been constructed, and Palmer found these unsatisfactory because they did not look historic. Banton agreed; in fact, he wanted only aged logs for the farm. [40] Maintenance Worker Elmer Stein searched the area for old farm buildings, and purchased the old Bryant house near Gentryville and a barn from the Reiss Family near Chrisney, Indiana. He went to Hodgensville, Kentucky, to study the appropriate construction techniques, and hired Oatis Tribbie and Abner Crews to lead the work crews. The park hired eight others,* all unemployed local residents, to disassemble the structures and rebuild them on the farmsite.

*The crew members were Fred Smith, Robert Longabaugh, Thomas Richards, Russel Frickes, Orville J. Day, Mason W. Bryant, Wayne Byers, and Donald Byers. Crews, Tribbie, Smith, and Longabaugh were rehired to work at the farm in 1969.

Generally, it took one day to knock down a structure, another day to move it, and approximately two weeks to rebuild it on site. When completed, the complex included a hewn log cabin (see Figure 7—5), hewn log barn with shed, a smokehouse, a corncrib, a chicken house (added later), and a workshop, all enclosed by split rail fences. The project cost $9,597.28. [41]

|

| Figure 7-5: The reconstructed cabin at the living historical farm, 1973. National Park Service photograph files, negative no. 1, photographed by Richard Frear. |

Ed Bearss' report and Ida Tarbell's The Life of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 1, provided the information needed for the selection of appropriate crops. [42] The farm featured oats, corn, flax, and cotton, cabbage, tobacco, peppers, corn, pumpkins, kidney beans, radishes, tomatoes, beets, rutabagas, cucumbers, potatoes, muskmelons, watermelons, and gourds. [43] Banton purchased open—pollinated yellow dent corn advertised in the Prairie Farmer magazine from Gordon Neal of Mount Vernon, Iowa. [44]* Northrup, King, and Co. of Minneapolis furnished the flax, [45] and the New York State Historical Association provided guidance in "growing flax based on nineteenth century practices." [46] Banton contracted with the Smithsonian Institution to study appropriate furnishings for the living historical farm in 1969, [47] and in 1977, Superintendent Bill Riddle contracted with Hank Waltmann of Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, to study period livestock and poultry. [48] Mia Feightner of Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa, did a thesis on "Clothing and Accessories Available to Pioneers of Southern Indiana, 1816—1830" and a "Handbook for Contemporary Reproduction of Pioneer Indiana Dress" complete with patterns in that same year. [49]

*When a corn blight attacked southern Indiana in 1970, all the farmers' fields turned brown within three days, except Lincoln Boyhood's yellow dent corn. Banton enjoyed teasing the local farmers by displaying some of his healthy corn in the rear window of his car. Albert W. Banton, Jr., Interview with author, Indianapolis, Indiana, September 19, 1985.

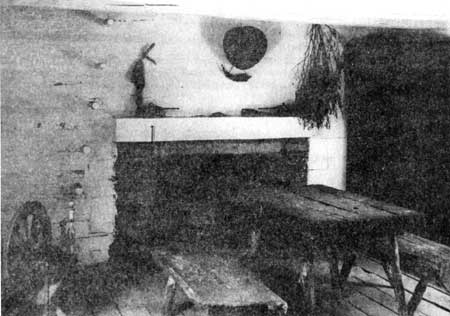

Banton used the information gathered by the Smithsonian to guide his maintenance staff in the construction of appropriate reproduction furnishings during the winter. Most were in place by the 1969 visitor season. [50] (See Figure 7—6.)

|

| Figure 7-6: Some of the cabin furnishings, 1967. National Park Service photograph files, negative no. 32, photographed by Albert W. Banton, Jr. |

In 1982, a visitor brought to the attention of the Lincoln Boyhood staff the existence of a log cabin displayed at Chicago's Century of Progress Exposition in 1933—34. The cabin, billed as "Lincoln's Indiana home," was purchased by Charles Garfield King. In 1945, King moved the cabin to Lake Forest, Illinois. The National Park Service has not been able to verify the cabin's authenticity. [51] Coincidentally, the Indiana Lincoln Union had considered the purchase of the Century of Progress cabin in 1935, but rejected the idea believing it would be better to construct a representative period structure than place one of questionable significance on the site. [52] That reasoning is still valid.

Interestingly, many of the issues discussed prior to construction of the living historical farm and other development rose again when the Denver Service Center prepared a second draft Master Plan for Lincoln Boyhood in 1973—74. [53] The second draft also contained some new ideas. Among the alternatives proposed by the Service Center were the relocation of the bronze cabin site memorial outside of Lincoln Boyhood; partial demolition of the cabin site memorial; relocation of the Trail of Twelve Stones and placement of the stones around the plaza wall; utilization of wagon carts to transport visitors from the visitor center to the farm; and adaptation of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln hall as a museum on Pigeon Creek life, including recordings of "Dennis Hanks" recalling life in the small community. Other issues included the possible relocation of the railroad traversing the park; relocation of County Road A west of the memorial, and closure of County Road B through the park. The Service Center dropped the alternative proposing adaptation of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln hall, and cost factors eliminated the wagon ride proposal. [54] Compliance and policy review restated the conclusions reached almost a decade earlier regarding the cabin site memorial and the Trail of Twelve Stones;* that is, they must remain in place. [55] Historian Roy Appleman's summary of the position merits quotation:

[At issue is] the ethical question of what liberty the Service may have in treating in the future the already developed memorial areas in the park as inherited from the State of Indiana. In general, . . . the Service should respect previously planned and executed memorial developments in an area, unless it can be demonstrate[d] beyond any doubt that a major error of information is involved. A previous generation, in these instances, has spent its money, energy, time, and veneration and love in these works, and they should not lightly be tampered with. [sic] Especially, they should not be bothered if only a difference in artistic taste is involved. [56]

*Apparently the regional office, Washington office, and Denver Service Center were unaware that park staff moved six of the stones several years before.

The policy review also addressed the presence of living historical farm. The Assistant Director for Park Historic Preservation, Robert M. Utley, and Midwest Regional Director Merrill Beal shared the concern that the farm detracted from the park's primary resources. Nevertheless, they felt it was acceptable as long as an appropriate level of attention was paid to the various resource types. As Utley stated:

If the living farm, in its present form, can continue to be operated in a way that does not detract from the park's legislated purpose as a memorial and does not jeopardize existing historic resources, its continuation may be justified. But to the extent that the farm's enhancement has now become the park's primary purpose and is being undertaken at the expense of historic structures [such as the proposal to move the stones and the cabin site memorial] and legislated theme, we recommend that a new planning effort be undertaken based on existing policies and actual park resources. [57]

Utley's position, with which Midwest Regional Director Merrill Beal concurred, forced a major revision of the draft plan. Proposals to relocate or remove resources put in place by the Indiana Department of Conservation were dropped. In response to Utley's remarks, the Denver Service Center planning team considered adding an alternative proposing the elimination of the farm, but decided it was not feasible. [58]

The major remaining issues focused on the closure and/or removal of roads and the railroad tracks. The early proposal concerning the railway recommended relocating the tracks so they would parallel the north/south boundary of the park. Further study showed that, while this would accomplish physical removal of the tracks from the park proper, it would not eliminate the visual and audible impacts of the railway. Further, the location of Heritage Hills High School 0.3 miles east of Lincoln Boyhood's eastern boundary precluded the safe relocation of the Cannelton spur to the proposed location paralleling the north/south boundary of the national memorial. Finally, the likelihood of the National Park Service obtaining sufficient funding to accomplish the relocation was extremely poor.

The Park Service's initial proposals concerning roads within the memorial boundary included the relocation of County Road A outside the west boundary of the park and the closure and obliteration of County Road B. Spencer County recommended that County Road A remain the same from the memorial's north boundary to Lincoln City, and that it follow an existing right—of—way within town. A third proposal suggested closing Road A from its intersection with County Road B to parking lot near the living historical farm. [59]

These issues drew considerable discussion at public meetings held in the visitor center on January 16, 1980. Public objections to the proposals centered around the safety issue and on potential interference with bus traffic to Heritage Hills High School. As a result of public comment, the National Park Service worked with Spencer County officials to develop the approved course of action. The General Management Plan provides for the relocation of County Road B to a site at the north end of the park—owned portion of the historic Lincoln farm; closure was deemed unfeasible because the road provided access to nearby Heritage Hills High School. Relocation of the railroad spur was determined equally unfeasible. The road leading from the visitor center to the interpretive shelter will remain, as will the existing entrance road. [60] Approval of the General Management Plan in 1981 ended discussion of major development issues at Lincoln Boyhood.

Within the first decade of its establishment, Superintendents Bob Burns and Al Banton accomplished all the major physical development planned for Lincoln Boyhood. The job that remains is the management and maintenance of the park's physical resources, and its interpretation of the Indiana Lincoln story.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

libo/adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 25-Jan-2003