|

Lincoln Boyhood

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 8:

Maintaining the Memorial

During the early years, Elmer Stein comprised the entire permanent maintenance staff at Lincoln Boyhood. Stein was an employee of the Department of Conservation who became a permanent National Park Service employee shortly after Superintendent Bob Burns entered on duty at Lincoln Boyhood.

Even in those early days, Lincoln Boyhood sometimes augmented the permanent staff with temporary help. When Clerk—Stenographer Charlotte Baird joined the staff in October of 1963, she assisted the superintendent in hiring 67 men. The National Park Service employed the men from mid—October through mid—January to do grounds work, primarily the clearing of underbrush in the forested parts of the park. Elmer Stein supervised the crew. [1]

More often, Stein worked alone, or with the assistance of one or two seasonal laborers. In addition to grounds maintenance, Stein cleared a fire line on the park's eastern boundary in 1964. He and Superintendent Burns refinished the floors and pews in the Abraham Lincoln hall that same year. Stein sanded the floor, Burns lay down on the pews, and slid along applying varnish as he went. Unfortunately, the varnish fumes caused Burns a terrible headache, and Stein was left to finish the job alone. Burns hired a woman to come to the park two days each week to clean the memorial building. [2]

The staff grew slightly during the Banton years, but the needs increased simultaneously with the completion of the visitor center addition and the two park residences. The construction of the living historical farm in 1968 further complicated the maintenance operation at Lincoln Boyhood. Maintenance at the farm involves costumed workers raising crops and caring for livestock using historical methods (see Figure 8—1). Al Banton hired separate crews for the farm and the more traditional maintenance duties, and Denny Beach continued the practice, although some crossover of duties existed. [3] The current superintendent, Norm Hellmers, uses some laborers primarily at the farm and others primarily for traditional maintenance work, but encourages the utilization of his maintenance staff for all duties. [4]

|

| Figure 8-1: Farmers John Varner and Clyde Bench working in the corn field, 1968. National Park Service photograph files, negative no. 376, photographed by Albert W. Banton, Jr. |

Over the years, the maintenance staff accomplished several major projects in addition to day—to—day care of the grounds and buildings. Although records for each year are not available, a selected review of projects undertaken at Lincoln Boyhood documents the resurfacing of trails; the installation of a water line servicing the visitor center; and resurfacing the visitor center parking lot, and the residential/utility road in 1971. The National Park Service hired °ree;a professional tree service to remove damaged trees that, same year. [5]

The first reports of leaks in the memorial visitor center's roof appeared in Lincoln Boyhood's 1972 annual report. [6] The problem recurred over the years, and several attempts to correct the problem proved unsuccessful. Finally, in 1985, the roof was replaced in kind at a cost of $50,000. Among the other projects undertaken by the National Park Service was the 1977 establishment of an environmental study area in a portion of the historic Thomas Lincoln farm never used for crop production; the park replanted the area and allowed the area north of the living historical farm structures to reforest. In 1980, a concrete walk leading from the plaza parking lot around the Nancy Hanks Lincoln hall to a rear entrance was added, and restrooms were adapted for handicapped accessibility. Safety handrailings along the steps of the courtyard were constructed in 1984 to provide safer access for visitors. In 1985, the park repainted the exterior of the water tank. [7]

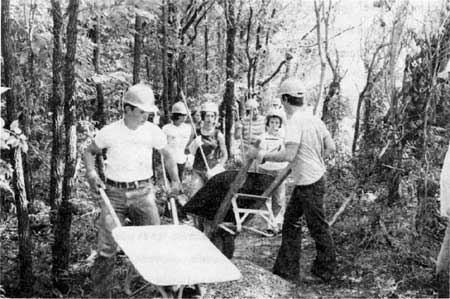

The introduction of Young Adult Conservation Corps (YACC) crews in 1978 greatly expanded the park's ability to undertake special projects. In Fiscal Year 1978, YACC crews cleaned and repaired picnic tables in Lincoln State Park, installed new signs, constructed barbed wire fences along the boundary, picked up trash, sanded benches, stacked logs, constructed new trails (see Figure 8—2), built a new trailer—port for the park's trailer—housing, maintained drainage ditches, and assisted in the renovation of the maintenance facility. [8] Young Adult Conservation Corps projects in Fiscal Year 1979 included re—sodding worn areas near the cabin, cleaning ox and cattle pens, washing and waxing park vehicles, cleaning windows and floors, trimming trees, painting equipment, posting boundary signs, improving the allee trails, rust—proofing and painting metal fences, unloading and stacking hay, running a water line to the drinking fountain, and painting curbs and parking stripes. [9] A similar variety of projects were recorded for YACC crews until 1981, when the program disbanded. In 1983, Lincoln Boyhood utilized the Comprehensive Education Training Act (CETA) program to hire youths to rehabilitate trails, and clean the grounds and visitor center; in subsequent years, Student Youth Employment Program (SYEP) crews were hired for similar projects. [10]

On one occasion, a maintenance project at Lincoln Boyhood was used to train maintenance workers from other Midwest Region parks. When the visitor center required repointing in 1977, Midwest Region restoration specialist Ray Kunkel conducted a training course in tuckpointing which was attended by two members of Lincoln Boyhood's maintenance staff, one from Lincoln Home, Illinois, two from Sleeping Bear Dunes, Michigan, and one from Apostle Islands, Wisconsin. (See Figure 8—3.) The week—long course received considerable attention in area newspapers. [11]

|

| Figure 8-2: Young Adult Conservation Corps (YACC) are building a new trail, 1977. National Park Service photograph files, negative no. 435, photographer unknown. |

In spite of the frustration mentioned by several superintendents concerning funding and staffing levels for maintenance, the program at Lincoln Boyhood has run smoothly. When resources were limited, most superintendents made the public areas their first priority; non—public facilities such as park residences and maintenance buildings have taken a back seat. Overall, the grounds and facilities have consistently been well—maintained.

|

| Figure 8-3: Participants of a 1977 training course repointing the memorial visitor center. National Park Service photograph files, negative no. 444, photographer unknown. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

libo/adhi/chap8.htm

Last Updated: 25-Jan-2003