|

OLYMPIC

Historic Resource Study |

|

II. HARD WORK AND SHATTERED DREAMS: SETTLEMENT

Permanent Settlement on the Peninsula

After the short lived Spanish military posts were established at Discovery Bay and Neah Bay, one hundred and fifty years passed before permanent white settlement of Peninsula lands took place. The tide of trans-American westward movement did not reach the Olympic Peninsula until the mid nineteenth century. In the 1850s settlers moved into this remote northwestern corner of the country and began claiming land around the east and north coastal fringes of the Peninsula. Land around the lower Hood Canal shoreline and in the vicinity of present-day Port Gamble, Port Orchard, Port Ludlow, Port Hadlock and Port Townsend was claimed by homeseekers. On the north Peninsula coast along the Strait of Juan de Fuca, settlers took up homesites around Port Discovery, Sequim Bay, Sequim, Dungeness, Port Angeles (then called false Dungeness), and Neah Bay (Lauridsen and Smith 1937, 9-12). Along the Pacific Ocean, early settlers arrived in the area of Grays Harbor.

During the next three decades, additional infant colonies were established around the Peninsula coastline at La Push (on the Pacific Ocean), at Clallam Bay, Pysht, Gettysburg, Crescent Bay (on the Strait of Juan de Fuca) and at Quilcene and Hoodsport (on the Hood Canal). Transportation and communication between these outposts and the mainland was tedious and sometimes nonexistent. By 1890, isolated settlements and individual homesteads circled the uninhabited inner core of the Olympic Peninsula (North Pacific History Company 1889, 173).

Gradually, homesteaders primarily interested in farming began to move inland. Reports of fertile valleys, rich bottom lands and abundant rainfall appeared in newspapers and official government documents. In early 1891 the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported the findings of the Gilmans' explorations into the Peninsula interior. The soil of the river bottoms, it said, are "of a rich, black sandy loam that raises a variety of crops and is particularly well adapted to the production of vegetables. The pasturage for sheep, hogs and cattle is excellent and the abundant rainfall renders failure of crops an impossibility" (Seattle PI, 1891, 1 January). Mother newspaper article entitled "Farms in the Olympics," and written by C. A. Gilman, described the river valleys west of the Olympic Mountains: "[They] are very fine bottom lands from one to four miles in width, timbered but lightly with very small cottonwood or brush and very cheaply cleared for farms" (Seattle PI 1890, 28 May). Lieutenant Joseph O'Neil, after returning from his 1890 trans-Olympic exploring expedition, also claimed that "the country on the west side of the mountains is capable of great possibilities; though the undergrowth is rank and luxurious, and the entire country heavily timbered, it is no more difficult to clear than are the farms of western Washington" (U.S. Congress 1896, 17). After successfully completing a number of expeditions across the Peninsula, the Gilman father and son team assuredly announced that the Olympic Peninsula "is attractive in all its features [and] it is reasonable to expect a rush of immigration. There is no great hazard in predicting that within five years the 'unknown country' of the Olympic Peninsula will be as well populated, productive and as easily accessible as any part of western Washington" (Seattle PI 1890b, 5 June).

The Gilmans' prediction of rapid increased population, productivity and accessibility was never fully realized. The survey team of Arthur Dodwell and Theodore Rixon found only eighty-three residents within the limits of the Olympic Forest Reserve in Clallam County at the turn of the century, although 341 homestead entries had been made. [The Homestead Act allowed any man or any single, widowed or deserted woman over twenty-one years of age to claim 160 acres of the public domain provided that he/she live on the land five years, make his/her home on it, cultivate the land, and pay fees of about $16.] They concluded that such a discrepancy "appears to furnish incontestable evidence that the experiment of farming under the prevalent conditions in this region has not proved profitable" (U.S. Department of the Interior 1902, 14). Other reports written only a decade later generally confirmed the Dodwell-Rixon findings. After 1906 when the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture opened up additional lands on the north, west and south sides of Olympic National Forest to homesteading, only sixty-three claims were filed and only 600 acres were under cultivation. Of the entire 2,300,000 acres available for agriculture on the entire Peninsula, only one and one-half percent was being farmed. Problems related to producing crops seemed numerous: clearing the land of huge timber stands and providing proper drainage for the soil were costly; river bottoms were narrow and subject to flooding; the ripening and harvesting of grains was difficult; and the distance from markets and often impassable road conditions inhibited the transport of supplies and produce (Burns 1911, 18-19; NFS ONF 1910, October). Many early settlers tired of the hardships encountered and abandoned their claims. Some found ways to adapt to the unique conditions of the Peninsula and stayed for years.

Settlers of the Peninsula interior generally established homesites around low elevation, large inland lakes or on the flatter bottom lands of the lower major river valleys. Lakes Crescent, Ozette, Quinault and Cushman were favored sites in the late 1880s and 1890s. Land on the lower sections of Morse and Ennis Creeks and the Elwha, Soleduck, Bogachiel, Hoh, Queets and Quinault Rivers was also claimed by early settlers. A few ventured to upper drainage areas. By the time white settlers arrived on the Peninsula, four Indian reservations were set aside at the mouths of rivers along along the coast: the Makah, the Quillayute, the Hoh and the Quinault. Between these reservations, early white immigrants settled on scattered plots atop wooded headlands or on flat, grassy coastal inland prairies (DNR Maps and Surveys).

Trails were the main means of travel for early settlers along the coast and in the interior Olympic Peninsula. At first, existing game and Indian trails were used, and, where available, the trails of transient trappers, prospectors and surveyors. Trails usually followed the paths of river bottoms or crossed hills and mountains at divides and low passes. Thick mud or swollen rivers often made trails impassable during wet winter and spring months. Horses were sometimes used to pack supplies and people into settlers' homesites. In the 1890s trails were prevalent but often impermanent. As settlers and their needs shifted so, too, did trails. Once a trail fell into disuse, it was usually obliterated by a succession of vegetation. In the late 1890s the Olympic Forest Reserve survey team of Dodwell and Rixon observed: "There are numerous roads and trails within the reserve—in fact, all of the surrounding townships have one or more wagon roads and numerous trails" (U.S. Department of the Interior 1902, 19).

Travel via the ocean or by rivers was sometimes more practical in certain areas of the Peninsula. Sternwheelers and Indian dugout canoes transported passengers and goods along the ocean shoreline to the mouths of rivers. Both the Queets and Quinault Rivers were navigable by canoe for several miles inland. At first native Americans were hired to transport the settlers and their supplies up the Queets and Quinault, but later the settlers themselves became skilled at poling dugout canoes through sometimes swift waters. High, cascading winter rivers were, at times, treacherous for canoe travel. Canoes were predominantly used on Lakes Ozette and Quinault. Early transportation across Lake Cushman was provided by raft; at Lake Crescent small ferry boats were introduced in the 1890s.

In the late 1800s railroad routes were surveyed along both the east and west side of the Peninsula. The imminence of these common carrier, north-south railroads raised the hopes and expectations of settlers and businessmen alike. None were ever completed. Isolation from the outside world was the nemesis of many early settlers in the Olympic Peninsula interior. Road building was a slow and often a prohibitively expensive proposition due to dense vegetation, prolonged wet weather and consequent short building seasons, numerous river and creek crossings and rugged, rocky terrain. A few early settlers' trails evolved into rough dirt or puncheon (split boards laid side-by-side horizontally across the road grade) roads. Many times roads never reached areas of settlement or, if they did, it was after a succession of settlers had come and gone. By 1930 those original settlers who had persisted in the face of remoteness from markets were served by a series of stub roads that penetrated the interior river valleys only a short distance.

The life of the Olympic Peninsula settler was tedious and wrought with difficulties. Subsistence farming was pursued by those settlers intent on making a life for themselves in the dense Peninsula forests and underbrush. "Proving up" on their homestead claims was a primary goal. Homestead entry laws required the completion of certain improvements within a specified number of years. All homesteaders began their "frontier" life by erecting a small cabin or house constructed from felled trees on or near their land. Serious homesteaders then immediately proceeded to clear a small plot for a small vegetable garden. Over the several years hardy settlers cleared and slashed (piled and burned) additional acreage. Cleared and cultivated fields ranged in size from one acre to thirty acres and were usually planted in grasses, clovers, or timothy. Crop rotation was customary. Peninsula homesteaders acquired a variety of farm animals including chickens, a few milk cows, one or two horses, pigs, and sometimes flocks of sheep or herds of cattle. Hunting and fishing were often pursued in fall and winter months to supplement the homesteaders' food source.

Invariably, settlers could not furnish all their needs through agricultural, hunting and fishing activities. Cash was needed to buy food, equipment and clothing. Settlers were usually compelled to take temporary or permanent jobs away from their homesite. They often sought employment as loggers, mail carriers, trail and road construction workers, surveyors, bounty hunters, guides and packers or seasonal Forest Service rangers. The early settlers, usually through a cooperative effort, found ways to satisfy their own particular educational, religious and social needs. Schools and churches were erected on land donated by settlers and resources pooled to employ teachers and clergymen. The social life of settlers was usually limited to visiting neighbors. Many settlers only stayed long enough to erect a cabin and "prove up" their claim. Others, fully committed to pursuing a life in the "wilderness," stayed a few years on their claim but eventually left when the hardships of Peninsula homesteading became overwhelming or the uncertainties of the administration of the Olympic Forest Reserve (and later, Mount Olympus National Monument) became too great.

Surrounded by a plentiful source of hemlock, cedar, spruce and fir, early settlers turned to the forests for all their major building materials. Initially, cabins were generally of log or wood frame construction, one to two stories in height, gable roofed and rectangular in shape. Cabin corner notches were predominantly saddle, or variations of the dovetail, notch. Wood frame buildings were sheathed with hand split or, sometimes, milled lumber. Roofing material was split shakes. When available, local milling capabilities influenced lumber dimensions and the overall dimensions of cabins. First generation cabins were often no larger than 12 x 14 feet. Cabins sometimes had porches that extended across the front facade, and small, multi-pane windows (and later double-hung sash windows) were placed sparingly in cabin walls. Fireplaces were extremely rare; heat was provided by wood stoves with flue pipes projecting through the roof.

Typically, a barn was erected after the homestead cabin. Barns, probably due to their size, were nearly always of frame construction with split board or milled siding. They ranged greatly in size depending on the permanency of the settler and the intensity and type of farming activity pursued; some barns were no larger than cabins or, on rare occasions, attained one hundred feet in length. Early barn siding was usually of wide, split vertical planks; slightly later, milled lumber was used for siding. Split shakes were the predominant roofing material. As early as the 1910s, concrete was sometimes used for foundation footings.

A variety of farm outbuildings complemented the cabin and barn. Depending on the settlers' needs, skills, and available resources, farm homestead building complexes might include a chicken house, a root house, a shed, an outhouse and a second barn or house, or even a blacksmith shop or sawmill. A well established farm sometimes had six or more buildings. Fences of various styles were an integral part of the early farming operation.

Areas of Settlement

The following subsections of this chapter first describe settlement along the Pacific coast in areas now included in the Coastal Strip of Olympic National Park. Subsequent subsections discuss settlement in each of the major river drainages and Lake Crescent, beginning with the Morse and Ennis Creek drainages on the north, then moving to watersheds on the western and southern sides of the Park, and finally ending with rivers draining the eastern side of Olympic National Park. General trends and characteristics of settlement in each drainage are often repeated in other areas of the Peninsula. However, the topography vegetation, rainfall, public administration of settled land, and the settlers themselves, in combination, are all quite different, yielding sometimes unique settlement patterns, histories and imprints on the land.

Coastal Settlement. The first white settlers arrived on the Pacific coastline of the Olympic Peninsula in the 1880s and early 1890s. Although the grassy prairies on the low inland plateaus were favored by those hoping to pursue an agrarian existence, several settlers established small settlement communities at the mouths of major rivers, notably the Quillayute, Hoh and Queets Rivers. Others took up scattered parcels of land along the ocean beaches. Indians living along the coast on the Quinault, Hoh and Quillayute Reservations were an integral part of these early settlers' lives. They often transported goods in their canoes, purchased goods from white stores and served as guides through the forests and prairies.

In 1890 the Sunday Oregonian reported that "on the Quilla[y]ute and its branches [there] are between 300-500 settlers" (Sunday Oregonian 1890, 25 May). Among the earliest arrivals in the Quillayute area were Frank T. (or William) Balch and several members of the Morganthaler family. Balch, a native New Englander, came to the area in the early 1870s and established the first store in the small community of Boston, approximately one mile from La Push at the mouth of the Quillayute River. The Morganthalers arrived in the Boston area in the late 1870's. The Boston post office, established in 1891, was located in Frank T. Balch's "trading post" and located near the fork of the Dickey and Quillayute Rivers just at the east boundary of the present Olympic National Park Coastal Strip (Harper 1971a, 487-95; Harper 1971e, 480-81; Ramsey 1978, 94). Kron O. Erickson, who first settled in the area in 1888, became the second Boston postmaster in 1898. He soon renamed the small fishing village Mora, after his home parish in Sweden (Ramsey 1978, 106). In 1898 William F. Taylor bought the store at Mora (Harper 1971e, 480). In the early 1890s Mora had a school house, at least one store, a saw mill and a "hophouse" (Harper 1971a, 487-95).

Near the mouth of the Quillayute River, another earlier settler in the area, Daniel Pullen, homesteaded and established a store at the small town of Quileut near present-day La Push. In 1881 Pullen succeeded Andrew J. Smith as postmaster at Quileut and renamed the post office Quillayute. In 1891 Pullen apparently occupied buildings located on the headland overlooking the estuary at the mouth of the Quillayute River (DNR Maps and Surveys). Other members of Pullen's family were among the first homesteaders on the Quillayute Prairie near the present-day town of Forks. Harriett Pullen, Daniel's wife, established the first post office at La Push 1883 (Harper 1971e, 480-81; Ramsey 1978, 79-82).

Supplies and mail for the colony of settlers at the mouth of the Quillayute River first came by small schooners from Neah Bay, several miles to the north. Canoes were used to transport goods up and down the Quillayute between settlers living up the Quillayute and the Pacific Ocean. In the early years fishing was a profitable industry along this section of the coast and a number of salmon trollers operated at the mouth of the Quillayute River. A fish hatchery and cannery were operated at the fork of the Dickey and Quillayute Rivers. After processing, cans of fish were shipped to Seattle by boat. Later, when the salmon run depleted, schooners no longer visited the Quillayute and the village of Mora atrophied (Harper 1971e, 480-81).

Like the Quillayute, the mouth of the Hoh River also attracted early settlers. By the late 1890s, J. W. Hank[s] located a homestead residence on the north bank of the Hoh River near its mouth (NARS:RG 49 1899). Isaac Anderson, a native of Norway, was another early settler who established a homestead near the mouth of the Hoh River around the turn of the century. In 1904 a post office was established at the village of Hoh, and Anderson served as postmaster for thirteen years (Ramsey 1978, 45). Approximately fifteen homesteads were claimed within five miles of the Hoh River mouth in 1899 (NARS:RG 49 1899). The Hoh Indian Reservation occupied a small parcel of land on the south bank of the Hoh. Later, Hoh village became known as Oil City.

Kalaloch Cove, at the mouth of Kalaloch Creek, was the homesite of Samuel R. Castile and Tom Lawder. Both Castile and Lawder came to live near the mouth of Kalaloch Creek around the late 1890s. Tom Lawder, a former Aberdeen building contractor, built a cabin and operated a cannery there (Aberdeen Daily World 1924, October). Beginning in 1903, Sam Castile operated the Castile post office out of his split board and shake residence. In 1907 the population of Castile was seventeen persons (Ramsey 1978, 44).

In the 1890s a small community of homesteaders made their home near the mouth of the Hoh River, just inside the Quinault Indian Reservation. In 1892 Carrie R. McKinnon was the first postmaster of the village of Queets. The post office, then located in a general store, served the native Americans on the reservation as well as the white settlers. Fishing and clamming were the village's local industry. I. C. Grindle was the operator of a fish cannery in Queets around the turn of the century (Ramsey 1978, 43; Aberdeen Daily World 1924, October).

Although river mouths were favored sites for the establishment of early homesites on the Pacific Ocean, settlers also built homes and cleared land along numerous small, short streams that emptied directly into the ocean. General Land Office maps and field notes dating from the 1880s and 1890s indicate the presence of settlers up and down the coastline from the southern end of Lake Ozette on the north to the Quinault Indian Reservation on the south. An intricate network of trails provided these early settlers with their only access to fresh water, inland prairies, nearby neighbors and the Pacific Ocean.

About three miles south of La Push, in the area now known as Third Beach, the Walter Edward Newbert family came to settle. Traveling from Seattle to Neah Bay and then by dugout canoe around Cape Flattery, the Newberts arrived at Third Beach, south of the mouth of the Quillayute River, in the fall of 1907. High atop a heavily wooded bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean, W. E. Newbert claimed 160 acres of land for the family homestead. He had discovered that the land was unmarked on official government land office maps when he supervised a 1903 railroad survey crew in the area under the direction of Theodore Rixon. Over a period of approximately three years, the Newbert family diligently and ingeniously worked to establish a more or less self-contained community on their acreage above the Pacific Ocean. Making use of wood and other materials at the site of an abandoned oil prospecting operation further north on the beach, the Newberts used salvage lumber to construct a cable tramway from the bluff to the ocean and to erect many of their own buildings. An old mine car was set on a short section of track built paralleling the bluff and used to move heavy building materials and supplies. The first house was completed on Grandmother Newbert's 160-acre parcel. In 1909 the largest building project undertaken, "Pa's House," was erected. Shortly afterwards, a schoolhouse was built for the Newbert children and for the children of Theodore Rixon and William F. Taylor who each had homesteads to the north and south, respectively. Other buildings, a burial plot and a telephone line to nearby Mora were additional amenities that enhanced the lives of these Third Beach pioneers. The Newbert's experiment of living in the wilderness was not long lived. In 1912 Walter Newbert's wife died and, presumably, the family left their homesite shortly afterwards (Daily News 1983, 23 January; ST 1962, 28 January). In the early 1960s several members of the Newbert family visited the old family homestead and found several of the original buildings standing, although in deteriorated condition (Pritchard 1982a, 1982b). A search of the Newbert homestead area in the summer of 1982 failed to uncover any remaining evidence of the structures or other cultural features.

Ozette Lake and Vicinity. Ozette Lake, whose western shoreline is approximately two miles east of the Pacific Ocean, had a heavy concentration of homesteaders prior to 1900. Third largest freshwater lake in the state of Washington, the relatively flat land surrounding the lake was reputed to be "good agricultural land." In 1892 U.S. Deputy Surveyor Lewis Shelton reported that "a large portion of the hill lands are almost 1st class in quality and will produce large crops of potatoes, turnips, and other vegetables, hops, oats, apples, pears, plums, cherries and small fruits" (DNR Maps and Surveys). At the time of the General Land Office survey, most of the land in T. 30 N., R. 15 W., encompassing the majority of the lake, was already taken by settlers. In 1892 a total of thirty-three settlers with improvements valued at over $11,000 ringed Ozette Lake (DNR Maps and Surveys). In ensuing years the population of Ozette Lake and the Big River Valley to the northeast peaked at about 130 families (NPS OLYM 1967, 5). Around the lake, homestead sites were only one-half to one mile apart (DNR Maps and Surveys).

In the early 1890s Ozette Lake harbored a distinctly isolated colony of settlers that was remarkably self-contained. For many years the only access to the lake from other Peninsula communities was by ship to the mouth of Ozette River which emptied into the ocean from the lake or by a twenty-five mile trail along the Hoko River to a small settlement at Clallam Bay on the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Early in the history of the community, settlers in the area attempted to satisfy their subsistence, social and educational needs. One homesteader established a partnership with a ship schooner captain to get supplies from Seattle through the Strait of Juan de Fuca and around Cape Flattery. A trading post was first set up in the home of a west shore resident. Later, other stores were located on other banks of the lake. At one time three post offices were located at strategic points on the lake and up the Big River Valley to the northeast. Two schools were established in the homes of lakeside residents; one on the west side in 1892 and a second on the east side four years later. Finally, a schoolhouse was erected by members of the community on one acre of land donated by a homesteader. Again, through a community effort, a church was constructed in the mid 1890s which also served as the parsonage for the resident minister (Arbeiter 1971a, 495-500; NPS OLYM ca. 1967, 4, 16-20). The jutting promontory where this early church was built is now known as Preacher Point.

The ethnic homogeneity of the Ozette Lake community was a distinctive feature of this isolated Peninsula settlement. After the pioneering settlers (comprised of N. P. Andrews, J. E. Johnson, Ole Boe, Ole Klaboe, the Isaksen and the Johnson families) first arrived at Ozette Lake in 1889, word of the promise and possibilities of free agricultural land in the area quickly spread to the friends and families of the original group. Land around the lake was quickly taken up by homesteaders, predominantly of Scandinavian extraction. Many were first generation emigrants from Norway and Denmark. Some of the area's early settlers' surnames, such as Andrews, Borseth, Christensen, Erickson, Jorgenson, Nielsen, Overgaard and Pedersen, reflect these national origins (Arbeiter 1971b, 510-16).

The life of members of this isolated Scandinavian community was aimed at self-sufficiency. Clearing the land was accomplished by felling trees by hand with an ax or cross cut saw. Large trees were removed by slowly burning the lower trunk with hot coals implanted in the base until the diameter was small enough to cut. Homes, barns and outbuildings were constructed primarily of sawn cedar planks. Most of the settlers engaged in farming, planting timothy, hay, potatoes, other vegetables and fruit trees. A few area residents, later on, cultivated cranberries which grew wild in some sections around the lake. Cows were brought in as early as 1891, and soon sheep and pigs were added to the stock. After herds were built-up, the surplus of cream and butter, as well as quarters of beef and pork, were packed out over the trail to Clallam Bay or taken to a small warehouse at Sand Point on the coast where they were shipped to Port Angeles or Seattle. Ozette Lake residents were not, however, able to sustain themselves through their efforts working with the land. Later, some even experimented with mining for gold on the coastal beaches just west of the lake (Arbeiter 1971a, 498-99; NFS OLYM ca. 1967, 11-14).

The Scandinavian community was short-lived. In 1897 when Ozette Lake was included in the newly created two million acre Olympic Forest Reserve, many settlers left, abandoning their homes, tools and heavier possessions that had been difficult to transport to the lake. Future prospects of expanding their community and gaining road access seemed dim (NPS OLYM ca. 1967, 20; 1937, 13). Early Ozette resident Ole Boe wrote in his memoirs: "It is like after the black death in Norway in 1300 when there remained only an isolated human here and there after the pestilence" (Douglas 1964, 181). By 1899 most of the early settlers had moved away (Arbeiter 1971a, 498).

Among those who stayed were Henry Borseth on Swan Bay; Ole and Sarah Erickson on Erickson Bay; August and Annie Palmquist and Ander (or Anders) and Johanna Nylund, both on the north end of the lake (NPS, OLYM 1937, 13; Arbeiter 1971b, 511-14). Today the only tangible evidence of this early group of settlers in Olympic National Park is the cemetery plot of the Nylund family located a short distance north of Ozette Lake near the site of the family home and now enclosed by a picket fence. The grave of Ander Nylund, who died at age sixty-four in 1920, is marked by a white cross. His son, Alfred, lies beside him.

The life of the Nylund family at Ozette Lake was similar to so many other early settlers in the area. Ander and Johanna were natives of Scandinavia (Finland and Sweden, respectively) and immigrated to Seattle in the late 1880s. After hearing of the Scandinavian colony at Ozette, they, with their two daughters, traveled by steamer and foot path to the lake in the spring of 1895. For ten years the family occupied an abandoned house on the north end of the lake, while Ander and Johanna worked to clear land, plant hay, fruit trees and vegetable gardens. Cows, chickens, pigs and eventually sheep were acquired. In season Ander fished in the Ozette River and hunted for deer, ducks and geese and other wild game. Sometimes he left home for months to work in a mine at Port Blakely. Johanna carded wool and spun thread from which she knit, crocheted and sewed clothing (Alcorn and Alcorn 1962, 151-54).

In 1904 Ander Nylund began building a new house. A year later the two story, nine room house with cedar siding, a split shake roof and wide wood flooring was completed. A large barn and various outbuildings completed the complex of buildings on the Nylund homestead. One by one, the Nylund children (Hulda, Inga, Annie and Ida) left the homestead to marry. (Alfred died in 1928 at the age of thirty from unknown causes.) After Ander Nylund died in 1920 Johanna remarried in 1932 and moved away from the Ozette Lake homestead. The Nylund house was never permanently occupied again (Alcorn and Alcorn 1962, 152, 155).

Gradually over time the buildings on the Nylund homestead deteriorated and fell down. By the late 1940s most of the small outbuildings had crumbled; by the early 1960s, the barn had collapsed and the house was overgrown with brush and entwined with ivy (Alcorn and Alcorn 1962, 155-56). In the mid 1960s only the shell of the Nylund house remained standing (NPS OLYM 1964, 18 February).

Just after the turn of the century, land bordering Ozette Lake was reopened for homesteading and a second wave of settlers arrived in the area. Many of these new arrivals moved into already existing settlers' homes and pursued a lifestyle similar to their predecessors. Among the group of latter settlers were A. C. Allen, F. W. Nourse, T. Potier, Albert R. Leake, Charles W. Keller, Henry Beldon and Bertie Caywood (Arbeiter 1971a, 498; NPS OLYM ca. 1967, 21, 27). Lars Ahlstrom and Peter Roose, who were among the second generation of settlers to Ozette area, established their homesteads one and a half to two miles west of Ozette Lake.

Peter Roose (born Arvard Hammerlund) and Lars Ahlstrom, like the first generation of Ozette Lake settlers, were Scandinavian. Born in Sweden, they immigrated to the United States as young men and arrived at Ozette Lake within ten years after the area was reopened for settlement. After becoming U.S. citizens, they filed for adjoining homesteads of approximately 160 acres apiece. Their neighboring homestead claims were located in open prairie land one and one-half miles west of Ozette Lake (NPS OLYM 1977, 22 March; 1980, 23 August).

Early years on their respective homesteads were occupied with constructing living quarters, farm buildings and fences, cultivating land and acquiring farm animals. Peter Roose at first built a log cabin structure for a house, and over the years added a shed, barn, root house, sawmill and endless yards of wood fences. Lars Ahlstrom erected a two story frame house as well as two barns, a shed, a chicken house and fences. The lifestyle pursued by both Roose and Ahlstrom followed a similar pattern. They each cultivated small plots of land and grew vegetables and fruit such as potatoes, carrots, onions, rutabagas, strawberries, and raspberries. These they used primarily for personal consumption. Chickens were raised principally for their eggs. Both Roose and Ahlstrom acquired flocks of sheep. By 1916, Peter Roose reportedly owned eighty to one hundred head of sheep (NPS OLYM 1977, 22 March). While occasionally the sheep were slaughtered for their meat, their wool, which was marketed in Seattle, was the principal commodity. To earn needed cash for supplies and equipment that Ahlstrom and Roose were unable to provide through their own labors, both men left their homesteads for several weeks each year to log, work in lumber mills or to take a variety of seasonal jobs in the area (NPS OLYM 1977, 22 March).

In the late 1920s and 1930s Lars Ahlstrom and Peter Roose replaced their original dwellings with new homes. After fire destroyed Ahlstrom's home in the late 1920s or early 1930s, he built a small one story structure, using large cedar tree trunks for corner supports. Roose, apparently after converting a Model A car engine to mill machinery, sawed his own lumber and erected a new house in the late 1930s (NPS OLYM 1977, 22 March; 1980, 23 August). Although Lars Ahlstrom's second house is considerably overgrown and deteriorated, both it and Peter Roose's second home, plus a few farm buildings on both homesteads, remain standing today. In 1983 Ahlstrom and Roose's homestead structures and small segments of picket and split rail fences are the only remaining testaments of the pioneering settlement way of life near Ozette Lake.

Some of the earliest settlers in the Ozette area claimed land on the prairie west of Ozette Lake and along the Pacific Ocean beaches. Before 1900, many prairie and beach residents were Scandinavian and were relatives or friends of the nearby Ozette Lake ethnic colony. Charles Willoughby and W. L. Ferguson established the first store in the entire area at the mouth of Ozette River on the ocean and, no doubt, supplied goods to many early immigrants who landed on the beach and trekked inland to the lake via a trail along the Ozette River. Sam Pederson, who eventually established the first store on the west bank of Ozette Lake, was at first in charge of packing freight for early settlers over the trail between the ocean beach and the lake. A. H. and Minnie Davis were among the earliest settlers to the area and claimed a homestead on the Ozette River between the lake and the beach (Arbeiter 1971a, 497; Ramsey 1978, 94, 103).

|

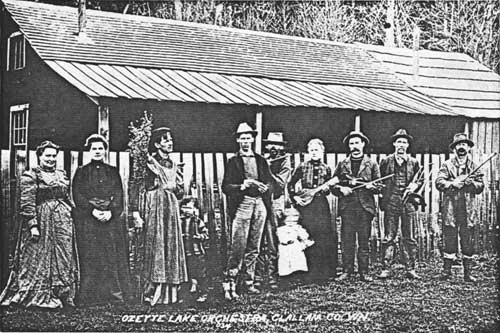

| Music, provided by the "Ozette Lake Orchestra," entertained settlers in the remote, predominantly Scandinavian Oette Lake community. (Courtesy Olympic National Park) |

Other early Scandinavian settlers built crude cabins along the beach, usually by fresh water creeks. Henry and Hilda Borseth and Iver Birkestol arrived in the early 1890s. Louis Larsen, John Substad, James Grant, W. Bank, C. Turner and Arnold Wink also built homes on or near the ocean (Arbeiter 1971b, 511-16; DNR Maps and Surveys). Near the mouth of Petroleum Creek (now in the area of Shi Shi Beach), two members of the Loveless family staked claims (DNR Maps and Surveys). Often the interest of these early coastal residents was not exclusively farming but mining for gold. Although many early coastal residents eventually moved their homesteads inland to Ozette Lake or ventured to Alaskan gold fields, not infrequently lakeside settlers looked to the ocean beach placer mining operations as a means to provide an income that would supplement their agrarian life style (ST 1961, 5 November).

The long-anticipated and hoped-for road that would break the isolation of the Ozette community did not arrive until after many settlers had come and gone. It was not until 1926 that a road between Clallam Bay and Swan Bay at the east side of the lake was completed. Another nine years passed before cars could be driven to the Ozette River at the north end of the lake. Electricity arrived at the lake in the early 1960s (NPS OLYM ca. 1967, 21; 1937, 19).

In 1940 President Franklin Roosevelt authorized the Public Works Administration to acquire the Ozette Lake area, as well as part of a long, narrow coastal strip, for inclusion in Olympic National Park. Eleven years later, in a memorandum written to the regional director of the National Park Service requesting professional assistance in evaluating historical values in the Ozette area, Olympic National Park Superintendent Preston Macy noted: "The Lake Ozette area represents the 'last frontier'. . . Most of these [Scandinavian] people abandoned their lakeshore homesteads many years ago, but they created them in real pioneer fashion. Practically all of the buildings have deteriorated beyond repair; in fact, many, if not most of them are gone" (NPS OLYM 1951).

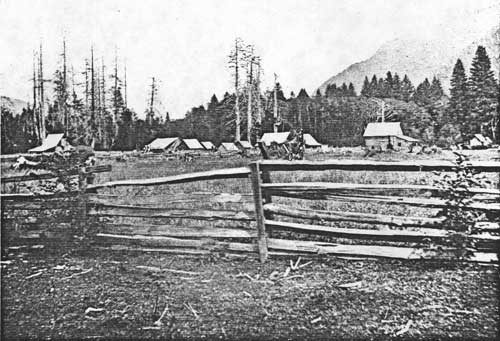

Morse and Ennis Creek Drainages. The first white settlement in the north Olympic Peninsula began in the early 1850s on low-lying river plains emptying into the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Between 1851 and 1890, dozens of settlers homesteaded and farmed on land on the lower sections of the Dungeness River and McDonald, Siebert, Morse and Ennis Creeks. The headwaters of both Morse and Ennis Creeks lie only a short distance south of where the jagged peaks of the north Olympic range, many of which rise to heights of over 6,000 feet. The upper valley floors were narrow, and sloping hillsides were densely forested with fir, hemlock and cedar. Trails into the area were primitive or nonexistent. Gradually, as less and less land for cultivating and grazing was available in the lower flood plains, settlers pushed into the foothills. Around the turn of the century, deposits of gold, silver and copper were discovered in some sections near the headwaters of Ennis and Morse Creeks and attracted hopeful prospectors to the area. In 1905 L. D. W. Shelton, U.S. deputy surveyor for the General Land Office, reported that T. 29 N., R. 6 W. (now lying within Olympic National Park) "is generally rough, broken and mountainous. There are numerous small parcels of good land in various portions of the [northern] surveyed part, mostly occupied by settlers" (DNR Maps and Surveys). Actual survey maps completed by Shelton in 1905 depict only six houses or cabins (located in Sections 1, 2 and 3) in the entire township (DNR Maps and Surveys).

John Fisher and his wife arrived in the upper drainage of Ennis Creek (T. 29 N., R. 6 W., Sec. 3) presumably after 1905 and filed homestead entry claims for two tracts of land totaling over 123 acres. By the late 1910s, a log house, a frame barn, a log root house, a shake storehouse and a half mile of wire fencing were constructed on the property, with five acres of land was under cultivation. Members of the Port Angeles based Klahhane (hiking) Club knew the Fisher "ranch" well, often hiking into the mountains past their homestead. The Fisher "ranch" was located seven miles south of Port Angeles by wagon road (DNR Maps and Surveys; Webster 1917). By 1921 Mr. and Mrs. Oscar Nelson were living on the property which they had named "Heart O'the Hills" (Webster 1921, 113). On the same wagon road leading up Ennis Creek from Port Angeles (T. 29 N., R. 6 W., Sec. 3) Henry John Dietz established claim to thirty-eight acres of a "rolling tract." In 1918 Dietz's homestead consisted of three acres of slashed land, a frame house and a shake shed (DNR Maps and Surveys).

South of the Ennis Creek headwaters and over the divide into the Morse Creek drainage, A. E. Cox, with the help of friends, cut a lengthy trail leading to a circular, level opening which he settled on in the mid to late 1890s. Cox arrived in the west in the early 1890s and stayed in Seattle in the height of the country's economic depression during the early 1890s. After moving to upper Morse Creek (known as Cox Valley on the most recent U.S. Geological Survey maps), Cox erected a log cabin and large shake barn and cultivated potatoes and hay. A friend named Wells filed claim on a larger open parcel nearby. Cox established his "ranch" when he was well along in years and presumably did not live on his property long. The Cox trail and ranch continued to be used as a stopping place by county game wardens, cattle drivers, sportsmen and campers in the 1910s and 1920s (Webster 1921, 57-59). The Cox trail is no longer in use today. All that remains of the Cox homestead buildings are collapsed piles of lumber and aging notch marks on trees that served to support the barn walls. None of the structures of these known early settlers in the Ennis Creek and Morse Creek Valleys are extant.

Elwha River Drainage. The Elwha River and its tributaries reach deep into the heart of the Olympic Mountains encircling Mount Olympus and its jagged, snow-capped neighbors on the east and south. The Elwha River extends further inland than most major Olympic Peninsula rivers, and its watershed takes in 175 thousand acres. Notable early exploring expeditions led by Joseph O'Neil in 1885 and James Christie in 1889-1890, found the Elwha Valley a natural pathway into the Olympic interior, and the river provided an original route of entry into the mountains (Wood 1968, 111). In 1885 the lower Elwha was considered one of the oldest settled parts of Clallam County (Report of the Secretary of the Interior 1885, 1091).

Settlement in the upper reaches of the Elwha River Valley, like other interior Peninsula valleys, did not occur until the late 1880s and early 1890s. In 1879 the Elwha south of Port Angeles was totally void of inhabitants (DNR Maps and Surveys). In 1885, when the party led by Joseph O'Neil traveled along the upper brushy slopes to the east of the Elwha River, the party found many traces of hunters and a "little old log cabin . . . under the brow of a protecting hill" (NPS OLYM 1885, 10). No other signs of white occupancy along the Elwha River were mentioned in O'Neil's account of the expedition (NPS OLYM 1885, 10).

By the late 1880s, however, two Norwegian brothers, Henry S. and Jake Hansen, were living in the upper Elwha Valley. After abandoning their original plan to claim land further up the river, they soon settled on plots near the confluence of Indian Creek and the Elwha in T. 30 N., R. 7 W., Sec. 29 (just north of the present Park boundary). Henry Hansen selected a small clearing on the south side of Indian Creek that was taken up by an earlier settler (Forsberg 1971, 322; DNR Maps and Surveys). Slightly to the east of Henry Hansen's homesite near the mouth of the Little River, William MacDonald built a cabin (in Sec. 28) on the east bank of the Elwha River. [Although the most prevalent spelling of this name is "McDonald" and appears as such in numerous books, articles and maps, a letter written and signed by William MacDonald asking Edmond S. Meany (writer for the Seattle Press newspaper) for compensation for assisting Press party members, shows the spelling as "MacDonald." Robert L. Wood brought this to general public attention in his book Across the Olympic Mountains: The Press Expedition 1889-90 (1967)1. In the winter of 1889-1890 the Press expedition, led by James Christie, encountered MacDonald's hospitality as the Press party was preparing for their navigation up the Elwha. Members of the Press party described MacDonald's cabin and clearing as the outpost of civilization" (Barnes and Christie 1981a, 167, 172, 182; DNR Maps and Surveys). William MacDonald shortly afterward (1891) became the first postmaster in the upper Elwha, and the hollowed out cedar stump which served as the original "McDonald" post office was a local landmark for many years (Ramsey 1978, 98; Forsberg 1971, 323-24). Henry Stringham succeeded MacDonald as postmaster in 1898 when he purchased the original MacDonald homestead. Paul Laufeld and his family of four soon after replaced Stringham at MacDonald's Little River clearing.

In the early 1890s others came and settled in the upper Elwha Valley near Indian Creek and Little River. South of Indian Creek and roughly one and one-half miles north of the Olympic National Park boundary were the homesites of Magnus Miller and Edwin Herrick. Miller and Herrick built their homes in 1891, about one-half mile from the west bank of the Elwha River (Forsberg 1971, 322; DNR Maps and Surveys). Herrick, a veteran of the Civil War, constructed a log house and later conducted a small grocery business on the Elwha. His son, Burt Herrick, became a guide and packer for hunting and fishing parties into the Olympic Mountains (Forsberg 1971, 324). On the east side of the Elwha River, near the Little River, Gus Raull and Harry Coventon selected homestead sites in the early and mid 1890s. Coventon was locally known for his work on several road and bridge building projects in the area, including the 1909 construction of the wood and steel Howe truss bridge built over the Elwha River south of the mouth of the Little River (Forsberg 1971; 322-23; DNR Maps and Surveys).

By late 1893, General Land Office Surveyor Henry Fitch located only three settlers in the entire township south of the Elwha junction of Little River and Indian Creek, now included in Olympic National Park (T. 29 N., R. 7 W.) (DNR Maps and Surveys). Around 1889, Warriner Smith built a cabin in the rugged, heavily forested slopes on the east side of the Elwha River near the mouth of Madison Creek. In December 1889, the Press expedition visited Smith's vacant cabin intent on constructing a boat that would carry the party deep into the Olympic range. Quite possibly, Warriner Smith's sawmill, located down river from his homestead cabin, provided the lumber for the intrepid Gertie (Barnes and Christie 1981a, 171; 1981b, 315, 320). Press party members invited Smith to Gertie's christening ceremony in late December; however, as Press leader James Christie wrote, business deprived us of the pleasure of his company, but he sent on a box of good cigars, which we fully appreciated" (Barnes and Christie 1981a; 167. For ten days in early February 1890, Press party members made themselves at home on Smith's Madison Creek claim while they waited for clear weather before continuing their trek. Expedition members described Smith's uninhabited cabin as log "with spaces between the logs from one to three inches with a loose sheeting inside of cedar shakes, a breezy and well ventilated cabin for this kind of weather" (Seattle Press 1890a, 16 July). Proceeding slowly up the Elwha River on a faint old trail, the Press expedition encountered one other evidence of white inhabitance on the Elwha River; the clearing and unoccupied cabin of Dr. A. B. Lull located about 100 yards from the Elwha River somewhere near the mouth of Griff Creek (Barnes and Christie 1981b, 317, 321). In the winter of 1889-1890, Dr. Lull's Griff Creek clearing and cabin were apparently the last outpost of white civilization on the upper Elwha.

Although hunters, trappers and possibly occasional miners probably wandered through sections of the upper Elwha, located within the present boundaries of Olympic National Park, the next known settlers on the upper Elwha did not arrive until the mid 1890s. From Tacoma, Washington, Ernst Krause, a German immigrant and painter, and his wife Meta, established a log house, barn, garden and orchard in a low valley shelf on the east bank of the Elwha River. They kept cows, horses, mules, pigs and chickens on their land. The Krause's were building a new home and clearing more land in the area when a slash fire they were tending swept out of control and consumed their homestead buildings and animals. (Apparently, at least one Krause cabin remained standing. Around the turn of the century, Grant, Will and Martin Humes and Ward Sanders spent time there. In 1932 Grant Humes and others destroyed this cabin (Dalton Collection 1916-1933).) Writing to his brother Will Humes (in letters dated 21 May 1917 and 28 September 1938), Grant Humes referred to the abandoned Krause cabin. Discouraged, the Krauses returned to Tacoma (NPS OLYM 1975, n.d.; Dalton 1982). A small, grassy opening with small hummocks of disturbed ground and scattered fruit trees are all that remain at Krause Bottom today.

At about that same time William Anderson homesteaded on a large acreage of property spanning the Elwha River near the confluence of Haggerty Creek. Over a period of nearly twenty years, Will (or Billy) Anderson cleared land, planted crops and fruit trees and grazed cattle on a section of valley bottom land along the west side of the Elwha River. Back from the water's edge on a terraced shelf, Anderson constructed a large barn, house, several outbuildings and fencing (Dalton 1982). In 1911 the Anderson "ranch" consisted of sixteen acres of cleared land of which four acres were slashed. One acre was planted in bearing fruit trees and the remainder was used for hay production and pasture. Near his property, Anderson and a man named Haggerty constructed a wood bridge across the Elwha River. According to a letter written by Grant Humes on 4 May 1927, Will Anderson was gone from his property by 1912 (Dalton 1982; Dalton Collection 1916-1933).

In mid fall of 1897 three easterners arrived in Port Angeles: two brothers, Will Humes, Martin Humes, and their cousin, Ward Sanders. Raised on a farm in upstate New York, they came from a family that guided and packed hunting parties in the Adirondack Mountains. Their purpose, however, was not to farm but to mine for gold, either on the Peninsula or, possibly, in Alaska. Immediately after settling temporarily in an unoccupied rancher's cabin about thirteen miles south of Port Angeles on the Elwha River, Ward Sanders dug into a ledge outcropping, hoping to find gold. Even while great mineral wealth along the Elwha River seemed doubtful, all three of the party were impressed by the abundance of deer, elk and fish in and around the Elwha. Will Humes wrote to his family on 5 December 1897: "We think we could do well hunting, even if no gold is found." Will also observed that "there is no end to good pasture land on both sides of the mountains here," and that "if we find a place suitable, we will settle down in the sheep business" (NPS OLYM 1897-1911, 1934). By March 1898, Martin, Will and Ward had taken up ranches in the upper Elwha: Ward and Will selected adjoining parcels between Idaho Creek and Lillian River; Martin's land was two to three miles upriver. Immediately, Martin and Ward began clearing land in preparation for gardens. Ward Sanders described their early settlement activities in a letter to his East Coast cousins dated 6 March 1898 (NPS OLYM 1897-1911, 1934).

Long, descriptive letters with prolific details about elk, deer, bear and "cat" hunting expeditions on the wooded slopes of the Elwha River were sent back to the Humes family in New York during Martin, Will and Ward's first two years on the Elwha. An avid hunter and lover of the outdoors a third Humes brother was attracted to the Elwha country. In late 1899 Grant Humes came to the Elwha Valley (NPS OLYM 1897-1911, 1934).

Shortly after Grant's arrival on the Elwha, Martin Humes left the area and in 1905 died in Idaho. In a letter written on 7 January 1905, Will Humes relayed the sad news of Martin's death to Myron Humes (NPS OLYM 1897-1911, 1934). Ward Sanders apparently stayed with his cousins for a few years and then also left, occasionally returning to visit. Soon after Grant arrived, he and brother Will built a cabin of hewn logs on the east side of the Elwha, north of the confluence with Antelope Creek (Dalton 1982). While hunting for elk, deer and cougar continued as a major fall sport, subsistence and cash producing activity, Will and Grant spent summers farming. On 20 February 1901, Will Humes described his farming plans for the next year:

I am going to be pretty busy this summer farming, as I am getting in readiness to keep beef cattle. Am going to build a barn, and plow up from 4 to 5 acres of new ground. Shall sow wheats and oats. Am also going to seed down a piece of alfalfa. . . . This is not much of a corn country. But it is a great grass and clover country. Last year I raised oats, wheat and grass enough to winter our six horses up to about March 1st, but this year I want to raise enough to winter as many as 15 head, though expect to have some cattle then (NPS OLYM 1897-1911, 1934).

A year and a half later Will reported to his brother in New York that he had erected a barn of pole construction with boards and shakes split from logs (NPS OLYM 1897-1911, 1934).

|

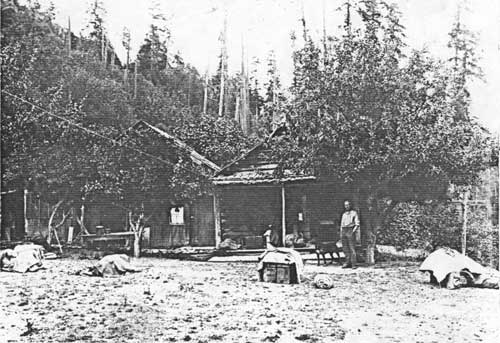

| In the early 1920s, the home of settler Grant Humes was the last homestead on the Elwha River. (Photo by A. Curtis, courtesy of Washington State Historical Society) |

With the increased number of mountaineering and sport hunting groups entering the Olympic interior, both Will and Grant engaged in an active packing business. In 1907 both Will and Grant assisted in packing and guiding The Mountaineers from Seattle and the Parker, Browne and Clark parties to the Elwha Basin and up the slopes of Mount Olympus (NPS OLYM, 1897-1911, 1934; Browne 1908, 195-200). (Writing to his brother on 10 November 1907, Will Humes described his involvement with packing the Parker, Clark and Browne party up the flank of Mount Olympus). The packing business during the fall hunting seasons was especially lively during the 1900s. In 1911 Will Humes wrote in a letter dated 24 March 1911 that he and Grant were "pretty well-known" by outdoor and sports enthusiasts from Seattle who gave them most of their business. In the same letter Will Hummes reported that he and brother Grant were planning to enlarge their house to provide expanded accommodations for summer and fall packing parties (NPS OLYM 1897-1911, 1934). During the long and damp winter months, (Will Humes noted in letters dated 10 November 1907 and again on 6 December 1910) that he and Grant often engaged in clearing and opening sections of trail along the Elwha River to facilitate the movement of pack horses (NPS OLYM 1897-1911, 1934).

About 1916, Will Humes returned to the East when the Humes' father died, never returning to live permanently on the Elwha River. Grant Humes remained at "Humes Ranch" pursuing a life of farming, hunting, packing and guiding, even as the community of settlers downstream grew larger and the flow of traffic on the Elwha trail increased. Grass was sown and harvested on the old Anderson ranch acreage and another lot near Idaho Creek to augment the supply of hay from the field below the Humes cabin. Each year Grant harvested a variety of vegetables from his garden. In the 1920s Grant often hunted for cougar in the mountains around the Elwha. Packing and guiding continued to provide Humes with a cash income even when other lower Elwha River residents, such as Burt Herrick and DeWitt Sisson, joined the trade. Grant, apparently, continued to pack for the Seattle Mountaineers hiking club, and his involvement with members of this group led to a long acquaintance with noted Northwest photographer, Asahel Curtis. After Will Humes returned to the East, Grant often hired assistants to help with packing in the summer and fall. As the Elwha River drainage became more and more a recreation area for outdoors people, Grant was sometimes hired to construct trails and seasonal hunting and fishing cabins (Dalton Collection 1916-1933).

Occasionally, Grant Humes made trips "out of the woods" to Seattle for a change of environment. Writing from Seattle to his brother Will in June, 1928 Grant commented on the city life he observed: "Everybody in the town is slaving for money—more money; always more. Yet they can only buy trash with it—not health, not youth, and all too often not contentment. The life they lead has no attraction for me and I am glad to get back to the cool, green woods and the peace and quiet and beauty to be enjoyed there" (Dalton Collection 1916-1933).

After several months of failing health, Grant Humes died in Port Angeles in 1934. Several years later the barn (in 1958) and structures adjacent to the cabin (in 1970) were removed by the Park Service. The legacy of the Humes family and the way of life of these early Elwha Valley residents are represented by the extant Humes cabin (circa 1900) now listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

The Krause family, Will Anderson and the Humes brothers were not the only early residents that settled in the upper Elwha River Valley. A latecomer to the upper Elwha, "Doc" A. Ludden, arrived on the east bank of the river around 1906. Abandoning a respectable life as a Tacoma city policeman, Ludden came to the Elwha when well along in years and established a home for himself on a terraced piece of land about one mile north of the Humes ranch. After first erecting a peeled pole and shake sided cabin, he gradually constructed more buildings on his raised bench of land, eventually creating a tight complex of structures composed of assorted angles and dimensions. Roofs and outer walls were sheathed with split cedar shakes. Characteristically ingenious and thrifty, "Doc" Ludden created windows from discarded photographic plates, furnished his dwelling with cleverly designed peeled pole tables and chairs and hand crafted implements and ornaments. On cleared land around his buildings, Ludden planted various fruit trees—apple, quince, plum, prune and pear—as well as raspberry and loganberry bushes, wheat, herbs, potatoes, kale, pumpkins, and other vegetables. He experimented with the horticulture of tobacco. Ludden may have been best known for his apiary industry. Ludden's bees provided him with quantities of honey which he sealed in cast-off milk tins. The bees wax he made into candles. On the outside wall of one of his buildings, Ludden advertised his homesite as "Geyser Valley House and Apiary." [The term "Geyser Valley" was first applied to the upper Elwha Valley by the Press party expedition in 1889-1890.] Ludden advertised himself as the Geyser Honey Man (NPS OLYM 1900-1911, 1934).

|

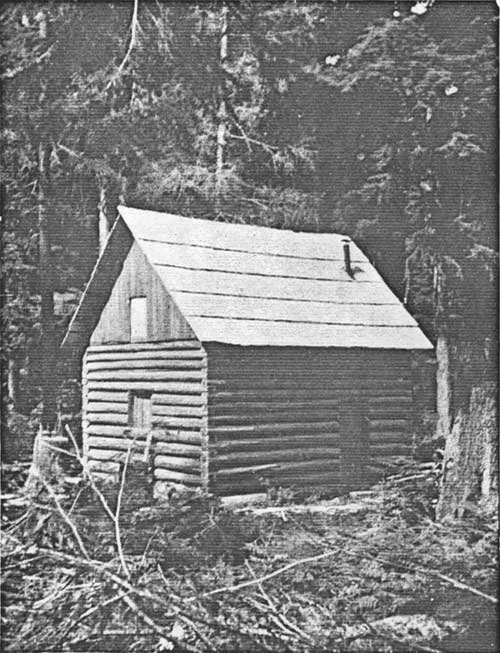

| "Doc" Ludden settled just half a mile below Grant Humes on the Elwha River. This 1914 photograph shows his house and a collection of outbuildings. (Courtesy of Olympic National Park) |

Signs of all kinds, in fact, were affixed to the outside walls of the various buildings in "Doc" Ludden's complex. Fashioned from flattened tin cans, his ubiquitous signs advertised "Meals and Bed," "Luddens," "Honey," "Vegetables," "Bread," "Stereoscopic Views," "Hair Cutting," "Root Beer," "Wine," and much more. As the Elwha River trail grew more heavily traveled with outdoors enthusiasts, "Doc" Ludden's establishment served as a quaint hostelry for hikers, hunters and fishermen. To advertise all that the Geyser Valley House had to offer, Ludden used a hand printing press to produce business cards and stationary. A sampling of printed verse on one of Ludden's personalized envelopes read: "FISH AND GAME TIS PLINTY, BE GORRY. AND, ITS A FOINE TABLE WE HAVE TODAY OR TOMORRY." "Doc" A. Ludden left his home on the Elwha in late summer 1927 and died in Port Angeles three months later. Nearby Ludden's Peak is named after him (Dalton Collection 1916-1933; NPS OLYM 1900-1911, 1934; NPS OLYM Historic photo collection). Although settling in the Elwha Valley, as in any rural and remote area of the Olympic Peninsula, required a variety of survival skills, "Doc" A. Ludden, more than others, seemed to capitalize on his life style as a unique, self-styled Renaissance man.

Nothing remains of "Doc" Ludden's tight cluster of buildings. Nearby, a single cabin now stands on the south side of the Ludden clearing. E. O. Michael lived on the property after "Doc" Ludden died and occupied the vacated Geyser Valley house. Michael was locally known for his marksmanship hunting cougar. In a taped interview with Port Angeles resident Russell Dalton, former National Forest and Park Service employee Jay Gormley reported that he, Gus Peterson and E. O. Michael built the cabin now known as Michael's Cabin, around 1937. Grant Humes frequently mentioned the whereabouts and activities of Michael in his letters to his brother Will Humes (Dalton Collection 1916-1933).

Lake Crescent. The settlement period on Lake Crescent lasted only briefly. Located only five miles south of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, this large inland body of water is surrounded by heavily timbered ridges rising 2,000 to 4,000 feet above the lake shoreline. There is one navigable stream linking the lake to the traveled waters of the strait to the north. To the south a high, narrow wooded ridge extends the length of the lake. Along the Strait of Juan de Fuca, settlers first came to Crescent Bay and Freshwater Bay in the 1880s. But it was not until the late 1880s and early 1890s that land claims were established along the Lake Crescent shoreline. Poor soil and rugged topography around the lake created an inhospitable environment for agriculture. It was the scenic beauty and abundance of soon-to-become-famous Beardslee trout that early settlers soon recognized as Lake Crescent's greatest resources. Even before the turn of the century, the first homestead claimant was providing accommodations for guests. Lake Crescent's recreational era began after less than a decade of homestead settlement (Harper 1971a, 425-35; PAEN 1953, 28 November).

Arriving in the Lake Crescent area by 1890, the seven original settlers in the area were John Smith, John Hanson, Paul Barnes, W. V. Wilson, George E. Kent, S. C. Pryor and Colonel Frank Gestring (Harper 1971a, 425-35; Lauridsen and Smith 1937, 209-10). John Smith who, with his wife Martha Gates, settled near Piedmont cut the first rough trail from Lake Crescent to Port Crescent on the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Swedish-born John William Hanson and his wife, Mary Laegar Hanson, homesteaded at the head of the Lyre River, less than one mile west of Piedmont. Sarah Barnes, with her son Paul, staked a claim on the south shore of the lake near the mouth of present-day Barnes Creek. (Other Barnes' family members soon followed.) At the west end of the lake W. V. Wilson settled on land near the present site of Fairholm (Lawrence 1971, 403-404). (The locations of other early settlers, including George Kent, S. C. Pryor and Frank Gestring have not been confirmed.) The original primitive footpath between Lake Crescent and Port Crescent was improved in the early 1890s. Enterprising Frank Fisher of Port Angeles initiated a packing business to carry supplies over the trail (Lauridsen and Smith 1937, 209). A surge of settlers followed and by 1891 and 1892 nearly twenty-five settlement claims were made on land in the Lake Crescent township (Harper 1971a, 425-35). In December 1892, U.S. General Land Office Survey or James T. Sheets recorded no less than fifteen settlers scattered around the Lake Crescent shore (DNR Maps and Surveys). In 1891 George Mitchell became the first postmaster on Lake Crescent with the office located on his claim at "Fairholme." Soon to follow was the Piedmont post office, established in 1894, under the directorship of settler William D. Dawson. A post office at Ovington's was not established until 1913 with Caroline Rixon serving as the first postmaster (Ramsey 1978, 95, 103, 115).

|

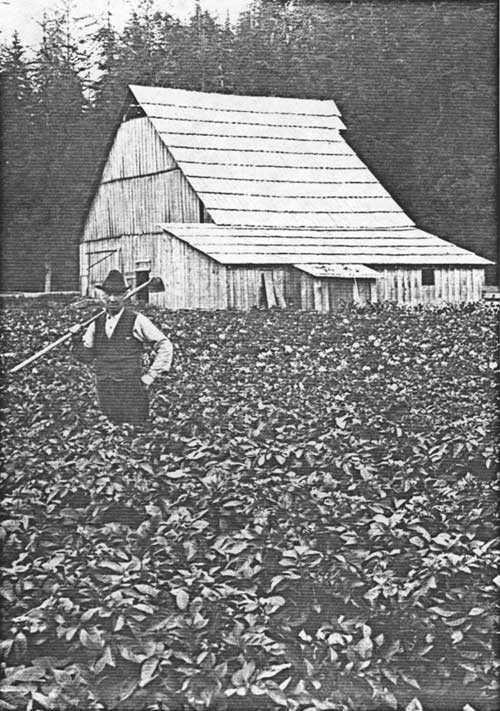

| A settler's home situated on the north side of Lake Crescent commands a grand view of the north Olympic Mountains, as depicted in this photograph taken around 1910. (Photo by A. Curtis, courtesy of Washington State Historical Society) |

Before 1891, travel between Lake Crescent homesites was by canoe. With training as a marine engineer, Paul Barnes constructed the first power driven boat in 1891 to ply the waters of Lake Crescent. Lady of the Lake, as the vessel was known, was launched near Piedmont and for two years monopolized trade between Piedmont and Fairholm. In 1893 William Dawson and Billy Smallwood constructed a faster, more powerful steamer named The Flyer (Lauridsen and Smith 1937, 210; Lawrence 1971, 403).

Early residents of Lake Crescent are not known to have engaged in extensive agricultural pursuits. Many original settlers apparently did not stay long, perhaps finding it difficult to exist on what the poor soil could produce. Those who did stay were quickly ensconced in the business of providing services for visitors who came to fish or simply retreat from busy city life. By 1909, the shores of Lake Crescent were dotted with inns and private cottages. Lake Crescent emerged as a resort area, eclipsing its period of settlement in less than two decades (Reagan 1909, 145).

Soleduck River Drainage. Early settlement of the upper Soleduck River, from Lake Pleasant eastward, occurred in the late 1880s and early 1890s. Although sections of this winding river are bounded by broad, level flood plains suitable for farming, the area is contained by high ridges on both the north and the south. As the river arcs to the southeast (where it enters Olympic National Park) and is fed by tributaries originating in the interior of the Olympic Mountain range, rugged, wooded hillsides descend more sharply to the river's edge. Nearly fifty miles of dense forest and rugged terrain separate the upper Soleduck from the Pacific Ocean to the west. And on the north, the Strait of Juan de Fuca lies ten to twenty miles away. Isolation from navigable ocean waters, undoubtedly, was a key factor delaying permanent settlement of the upper Soleduck River.

Access to the upper Soleduck River was originally provided by three routes. On the Strait of Juan de Fuca to the north, Clallam Bay and the town of Pysht were the points of origin for two trails cutting over the mountain ridges to the Soleduck Valley. A third access route for early pioneer settlers was from Port Crescent on the strait south to Lake Crescent and from Fairholm on the west end of the lake over a low divide into the upper Soleduck Valley. Between Lake Pleasant and Lake Crescent, Otto Dimmel, Jacob Fasel, Charles Jones and Arthur and Fancis Moore were among the first pioneers to reach the Soleduck in the 1880s. By the early 1890s, several families laid claim to parcels of land on both the north and south sides of the meandering course of the upper Soleduck River. In 1891 Soleduck River resident named Charles Jones established a "colony" of twenty-five settlers on the upper Soleduck River. By 1893, many newcomers filed for timber claims which were easier to obtain and had fewer requirements for "proving up" than homestead entry claims (Harper 1971a, 487-95; 1971b, 466-67; ST 1965, 19 September).

After the initial task of erecting a shelter, most early settlers cleared land and attempted farming, cultivating vegetables such as potatoes, cabbage and rutabagas. Salmon was fished from the river in the fall. Farming invariably failed to provide all the needs of the homesteaders, and often paying jobs were secured during at least part of the year. A few living along the river engaged in other activities beside farming. Trail packers, teachers, store proprietors and postmasters were needed to serve the linear settlement that stretched along the river (Harper 1971a, 487-95; ST 1965, 19 September). Early post offices on the upper Soleduck River between Lake Pleasant and Lake Crescent included the Tyee, Beaver, Collins and Wineton post offices. None but the Beaver post office (at a new location) still exist (Ramsey 1978, 99, 101, 116.)

In 1892 Arthur H. Moore served as first postmaster of the Wineton post office on the north bank of the Soleduck River, four and one-half miles west of Fairholm on Lake Crescent and now at the western boundary of Olympic National Park. Not far from the post office was a store operated by a member of the Moore family. Arthur Moore was an early settler on the Soleduck, arriving in the 1880s. In addition to conducting business at his store, Moore also packed freight into the Soleduck River. Other members of the Moore family lived within a mile of the store in the early 1880s. A General Land Office surveyor's map of 1892 shows that Moore had neighbors spaced roughly half a mile apart along the Soleduck between the junctures of Camp Creek and the North Fork Soleduck River (almost all of which was included in T. 30 N., R. 10 W.). Along the present western boundaries of the Park were the homesites of Ernest Boehrig, George C. Icke, a Mrs. Hunter and a Mrs. Brown. Further up the Soleduck River beyond the confluence of the North Fork Soleduck, a few cabins of unidentified ownership were scattered at greater distances (Ramsey 1978, 99; Harper 1971a, 492; DNR Maps and Surveys).

Undoubtedly, much of the early construction of cabins was accomplished by hunters, squatters or short-term residents. Many early settlers on the Soleduck River were neither economically nor physically prepared for the rigorous and impoverished existence that life on the upper Soleduck offered. Many moved away. Today there are no extant structures built by these early Soleduck River settlers within Olympic National Park.

Further up the Soleduck River beyond the juncture of the North Fork Soleduck, early settlers and visitors traveled through the upper reaches of the drainage, yet nothing is known of any permanent settlers. Although Theodore Moritz is credited with the discovery of Sol Duc Hot Springs in the early 1880s (located more than six miles beyond known permanent settlement along the river), the hot springs was not permanently inhabited until several individuals made efforts to commercialize the mineral water after 1900 (PAEN 1953, 28 November).

Bogachiel River Drainage. The section of the Bogachiel River drainage far into the interior of Olympic Peninsula now inside Olympic National Park had few early permanent settlers. Even more than the upper Soleduck River, the upper Bogachiel River watershed and its major tributary, the Calawah River, were distant from supplies and markets. By river, the Pacific coastline was more than twenty-five miles to the west and shoreline conditions there were not conducive to navigation or docking of large vessels. Travel on the Bogachiel River was often difficult. The upper Bogachiel and Calawah Rivers cut through characteristically steep, broken and mountainous terrain. Around the turn of the century, certain species of evergreen, particularly spruce and cedar, grew to their greatest height and diameter in townships transected by the Bogachiel. Dodwell and Rixon, while conducting their survey of forest conditions in the Olympic Forest Reserve in the late 1890s, observed spruce (in T. 27 N., R. 11 W.) that attained a diameter of more than five feet (U.S. Department of the Interior 1902, 66). Clearing land for homesteads was not only expensive but arduous and time consuming. Conditions for settlement in the upper Bogachiel drainage were less than ideal.

Early settlement of the Bogachiel River, like other sections of the Peninsula interior, occurred in the late 1880s and early 1890s. By late 1891, General Land Office Surveyor George Kline recorded no less than twelve settler's structures in T. 27 N., R. 12 W., now at the western boundary of Olympic National Park. Most were scattered along both sides of the Bogachiel River and spaced one-eighth to one- and one-half miles apart. Among these early settlers were J. Henne, George M. Hemphill (near the confluence of present-day Hemp Hill Creek), C. P. and E. Roarks, Chris Morgenroth (near the mouth of "Morganroth" Creek), Peter N[i]elson, John Shaw and Lewis Chase. At that time there were very few settlers located further upstream in the eastern adjoining township (now included in Olympic National Park) (DNR Maps and Surveys).

Although many of the early Bogachiel pioneers homesteaded along the river only briefly, new settlers continued to arrive during the 1890s. In 1892 the Bogachiel post office was established on the Bogachiel River near Hemp Hill Creek. Jacob A. Lochbaum, Henry Cotler and Morris Fehuley served successively as postmaster in the early and mid 1890s (Ramsey 1978, 33). In the late 1890s, while conducting an examination of the Olympic Forest Reserve, superintendent of Washington State Forest Reserves, D. B. Sheller, found "several" settlers scattered along the Bogachiel River (Rakeshaw 1955, 132). Many Bogachiel River settlers were agitated when, in 1897, their homes were included in the Olympic Forest Reserve. Protesting, twenty Bogachiel residents signed a petition requesting that their homesites be eliminated from the reserve. Siogners of this 1899 petition included "Christ" Morgenroth, Peter Nielson and Otto and "Theodor" Siegfried (NARS: RG 49 1901, 7 March).

Chris Morgenroth, whose Bogachiel River homestead was located just one mile west of the present Park boundary, eventually abandoned his homestead on the Bogachiel River. Later, recollecting his and other homesteaders difficulties on the Bogachiel, he said "we wanted farm land. Our idea was that we were going to pioneer and develop the West, but there were no markets, no roads, no trails, and we did not get any for at least thirty years afterward" (U.S. Congress 1936, 43). In 1905 Morgenroth joined the U.S. National Forest Service and, as one of the earliest rangers on the Olympic National Forest, cut many trails in the upper Bogachiel and Hoh River drainages (Historic American Buildings Survey WA—155 1983; NFS ONF 1912, n.d.). After Morgenroth left his homestead, his buildings were rented and occupied by a succession of settlers intent on making a life for themselves on the Bogachiel (Smith 1977, 19, 31).

A few early settlers remained on their homestead for years. Otto Siegfried came to the upper Bogachiel in the 1890s and settled on land about one mile below (west of) the Morgenroth homestead. There were two sons and a daughter in the Siegfried family. Although one son, Theodor, eventually moved to Seattle, George Siegfried stayed on the homestead most of his life. During the 1910s, George Siegfried's wife, Nell, taught native American children in a schoolhouse located across the river from the Siegfried home (Smith 1977, 17-18). In 1948 the Siegfried homestead still appeared on a map of Olympic National Forest (U.S. Department of Agriculture 1948).

Peter and Ora Brandeberry arrived on the Bogachiel River just outside the present Park boundary in the early 1920s. After first filing for a homestead claim on the nearby upper Hoh River in 1906, Peter and Ora and their family of seven children moved to the Bogachiel River which was slightly closer to the town of Forks. In their early days on the Bogachiel a horse trail provided the only access to the outside world. Similar to other homesteaders on the Peninsula, the Brandeberrys pursued a life of subsistence farming, on first the Hoh and later the Bogachiel Rivers, raising crops and cattle, and hunting and trapping in winter. For cash, Peter Brandeberry (as well as son, Harold) worked seasonally for both the National Forest Service and the National Park Service at various times during their tenure on the west side of the Peninsula. Over the years, the Brandeberry family members built one or two cabins upriver from their farm property on the Bogachiel River. Inside the Park boundary, the only known tangible evidence of white settlement along the Bogachiel River in 1983 is the decayed remains of one Brandeberry trapping cabin (Brandeberry 1983).

Hoh River Drainage. Like the Bogachiel, the upper Hoh River drainage presented great challenges for early settlers. Large, old-growth trees of sometimes immense diameters, thick undergrowth and remoteness from markets, were features confronting settlers. From the headwaters of the Hoh and its tributaries in the interior Olympic range, to the tidewater of the Pacific Ocean, the Hoh River descends more than 7,000 feet in about fifty miles. The cascading volume of the river is increased by an average annual rainfall of 145 inches (Fletcher 1966, 218). The river is steep, swift and difficult, even dangerous, to navigate. Flooding often occurs and, yearly, river banks are created and swept away. Although the valley floor is somewhat wider than that of the Bogachiel River, bottom lands often have soil that is unsuitable for agriculture and are susceptible to flooding. Surrounding terrain along the upper Hoh River is steeply rolling and broken and in some places rugged and mountainous. Homesteading along the upper Hoh River was not undertaken until the early 1890s.

Two brothers, Cornelius and John Huelsdonk, were possibly the earliest to settle on the upper Hoh River. While working on a Seattle-based land survey crew, John Huelsdonk first encountered the Hoh region in the early 1890s. In 1891 John and Cornelius Huelsdonk traveled from Seattle to the Olympic Peninsula in search of suitable land open to settlement. After claiming land along the upper Hoh, they erected a cabin and cleared a small acreage for a garden. John then returned to the Huelsdonk family in Council Bluffs, Iowa, married his foster sister, Dora Carolina Wilimina Wolf, and returned to the Hoh Valley in the fall of 1892. Soon, others in the Huelsdonk family traveled to the West taking up residence on the Hoh River. Over time, members of the Huelsdonk family that formed an enclave of original Hoh River settlers died or moved away until John and Dora Huelsdonk were the only family members that remained (Fletcher 1966, 226-27). The original Huelsdonk "ranch" was located just two miles outside the present western boundary of Olympic National Park.

The life of John and Dora Huelsdonk was representative of the quality and character of the lives of many settlers who came to the interior watersheds of the western Olympic Mountain range seeking homes. During their long residence on the Hoh River, the Huelsdonk family depended on a variety of activities to subsist. Soon after the family first arrived on the Hoh, John Huelsdonk worked seasonally in a logging camp away from home to earn cash for purchasing needed supplies. At the homestead he was routinely occupied with clearing land, erecting farm buildings and fences, cultivating a garden, grazing cattle and sheep, backpacking for hunters, geologists, timber cruisers and surveyors, and hunting and trapping. When state bounties were offered for killing predators, John Huelsdonk hunted cougar to earn cash (Fletcher 1966, 227-28). Later, Huelsdonk earned wages building trails in the Olympic Mountains for the National Forest Service (Smith 1977, 53). Dora Huelsdonk's life was equally rigorous, raising four children and tending to a variety of family chores. Travel for the Huelsdonks, as for other early Hoh River settlers, was limited primarily to canoe and primitive trails. The staple diet of the family was vegetables and bread. Humorously, it has been said that conditions on the Hoh afforded only a very monotonous cuisine consisting of "spuds and elk for breakfast, elk and spuds for lunch and at night the same with sauerkraut" (Fletcher 1966, 224).