|

OLYMPIC

Historic Resource Study |

|

III. SKID ROADS AND SLUICE BOXES: COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT AND INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT

Timber Exploitation

Early Peninsula Logging. The seemingly endless sea of mammoth trees along the Northwest coast always impressed early European and American explorers who sailed through the Strait of Juan de Fuca and explored the numerous bays and coves of the islands and shorelines to the east and north of the Olympic Peninsula. Viewing the heavily forested coastal areas from their seafaring wooden vessels, these voyagers were immediately cognizant of the utility of the erect tall trunks of shoreline coniferous trees. Written narratives of voyages made by Spanish, English and American mariners in the last quarter of the 1700s record the use of native trees for needed ship parts. Mizzen masts, foremasts, fore-top masts, small spars and even planks were fashioned from native shoreline trees by the crews of Captains James Cook, John Meares and George Vancouver. Captain George Vancouver, sailing through the Strait of Juan de Fuca and north through the Gulf of Georgia in 1792, was impressed with the abundance and quality of the forests he observed, noting that the surrounding country was "abounding with materials to which we could resort; having only to make our choice from amongst thousands of the finest spars the world produces" (Meany 1935, 51). In the late 1700s and early 1800s the Northwest coast gained a widespread reputation among the navies of Europe for its abundant source of excellent shipbuilding timber (Meany 1935, 47-51).

Arriving at the mouth of the Columbia River, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, after completing their two-year trans-American trek (1804-1806), wrote in their journal: "The whole neighborhood of the coast is supplied with great quantities of excellent timber. [The species of fir] grows to an immense size, and is very commonly twenty-seven feet in circumference, six feet above the earth's surface: they rise to the height of two hundred and twenty of that height without limb. We have often found them thirty-six feet in circumference" (Horn 1943, 69-70).

The earliest utilization of the Pacific Northwest's forest resources was not long to follow. In 1827 Hudson's Bay Company established the first mill in the Pacific Northwest at Fort Vancouver located on the north bank of the Columbia River. Six years later this Northwest fur trading company began lumbering at their second post, Fort Nisqually, 100 miles north of Fort Vancouver. In the mid 1840s mill machinery was purchased from Hudson's Bay Company by a small group of settlers and in the winter of 1846-1847 the first power mill on Puget Sound was set up near the present site of Olympia, Washington (Meany 1935, 59, 97-98).

The construction of mills around Puget Sound occurred rapidly in ensuing years. With the sharply increased demand for lumber in California during the decades following the gold rush, and as greater numbers of East Coast sailing vessels found their way to the region and spread word of of the immense stands of timber, outside capital was attracted to the Puget Sound area. Within ten years of the first commercial mill establishment, sixteen mills were scattered the length of the sound area. A mill at Port Ludlow was established on the Olympic Peninsula at the north of the Hood Canal around 1853. In 1855 the newly constructed mill at Port Gamble, built by San Francisco capitalists, W. C. Talbot and A. J. Pope, and experienced Maine lumbermen, J. P. Keller and Charles Foster, was producing 40,000 board feet daily (Meany 1935, 103, 121). Located at the mouth of the Hood Canal just opposite the east shore of the Olympic Peninsula, the new Port Gamble mill, known as the Puget Mill Company, produced nearly three times more than any other Puget Sound mill. It was physically the largest mill in the West, measuring fifty-five feet wide and 250 long (Morgan 1955, 62). By the early 1860s, 70,725,000 feet of lumber were produced along the waterways of Puget Sound (Meany 1935, 121-22).

Over the next thirty years, lumbering became a major industry for many coastal settlements on the Olympic Peninsula. In the Puget Sound area nearly all merchantable trees along the hundreds of miles of shoreline were felled and pulled by ox teams across greased skid roads to tidewaters where they were floated to waiting tidewater mills. Skid roads, made by placing logs twelve to eighteen inches in diameter across the trails, seldom extended more than two miles into the woods (Morgan 1955, 65).

In 1878 Eugene Ellicott observed, "The upper part of Puget Sound generally speaking is just about as I imagined it was 100 years ago. It is perfectly wild, just a howling wilderness. It has all been logged over; you see everywhere the remnants of logging roads. The mill companies have taken all the good timber near the shore" (University of California 1878, 9). On the Strait of Juan de Fuca the Port Discovery Bay mill, established inside Discovery Bay in the early 1860s, was a large consumer of logs for many years. Between 1860 and 1890, major logging operations were initiated at Port Angeles, Crescent Bay and Gettysburg on the north Peninsula shoreline. On the Pacific Coast the first commercial logging operations began in the early 1880s at Grays Harbor. In 1885 in an official report given by the governor of Washington Territory, lumbering was listed as one of the principal industries of all of the Olympic Peninsula counties (Report of the Secretary of the Interior 1885, 1091, 1096-1098, 1103-1104). Statewide, the number of mills increased from forty-six in 1870 to 310 in 1890 (Coman and Gibbs 1978, 211). During this early period, three Peninsula logging companies emerged as leading firms in the state: Pope and Talbot based in Port Gamble, Polson Brothers Logging Company in the Grays Harbor area, and Simpson Logging Company located in Shelton.

As logging operations developed around the outer fringes of the Peninsula and more and more readily accessible timber was taken from tidewater rivers and coastal areas, lumbermen began looking inland for a continuing supply of trees. The late 1880s and 1890s were years of interior exploration and survey work. Numerous written accounts of the interior's vast timber reserves were reported in popular literature and government documents alike. An article appearing in an 1896 issue of the National Geographic magazine, authored by the 1889 exploring expedition of the father and son Gilman team described the interior mountains as "gowned with dense, dark evergreen forests, reaching far down into cavernous depths of canyon and ravine" (Gilman and Gilman 1896, 135). After Lieutenant Joseph O'Neil led scouting parties across much of the southern section of the Olympic range in 1890, he reported to the U.S. Congress:

There is a great wealth in this district, and that is its timber. It seems to be inexhaustible. A story was told by a man sitting near me in a dining room. He said that they tried to dissuade him from coming to Grays Harbor, saying that there was nothing there, and elk walked across the mouth of the harbor at low tide without wetting their bellies. "When I came," he remarked, "and found a vessel drawing 17 feet in the harbor and 22 feet on the bar, I concluded that a country that grew timber 12 feet in diameter and elk with legs 22-1/2 feet long was good enough for me" (U.S. Congress 1896, 18-19).

O'Neil continued, "I could not quite agree as to the elk, but I have measured many trees over 40 feet in circumference, and some over 50 feet" (U.S. Congress 1896, 19). O'Neil expedition team member and botanist Louis F. Henderson was, likewise, impressed by the size of the trees encountered in the Olympics, noting that the "western arbor-vitae, called commonly 'cedar' . . . about Lake Cushman, together with the Douglas spruce, are of gigantic proportions, rivaling the famed redwoods of the Californian forests" (Henderson 1907, 163).

The interior expeditions of the Gilmans, O'Neil and others, coincided with the first wave of settlement into the Peninsula's interior river valleys and around the large land-locked lakes—Crescent, Quinault, Cushman and Ozette. Homestead claimants, intent on pursuing a life of subsistence agriculture, cleared timber from river bottom lands by felling, slashing and sometimes burning trees and underbrush from selected, relatively small parcels of potential agricultural land. Both the U.S. Homestead Act of 1863 and the Timber and Stone Act of 1878 permitted and encouraged the clearing of land (usually no more than 160 acres), with the latter act specifically designed to allow miners and settlers to obtain timber and building materials from undeveloped lands for construction on their sites (Frome 1962, 37). Some of these small acreages of early cleared land are within the present boundaries of Olympic National Park, principally along the Queets River and in the broad upper Quinault River Valley.

Railroad Logging. While noncommercial logging practices were pursued by interior Olympic Peninsula settlers in the late 1880s and 1890s, commercial logging operations at the Peninsula's outer fringes were entering a period of evolutionary change. The fluctuating, yet nonetheless steadily increasing demand for Northwest lumber, combined with the need for ingenious solutions to the distinctly unique regional problems of rugged terrain, inaccessible stands of oversize old-growth timber and distant markets, prompted revolutionary changes in the technology of the lumber industry in the Pacific Northwest and on the Olympic Peninsula. Beginning in the 1880s and continuing past the turn of the century, steam power replaced ox- and horse-driven log hauling teams in the form of the Dolbeer donkey engine. By 1900, 293 donkey engines were reported in use in western Washington logging camps (Meany 1935, 246). At the same time, with the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1883, not only were Eastern markets brought closer, but rail transport of downed trees at logging sites and finished lumber at mills became a viable possibility. By 1889, two railroads at the southern end of Puget Sound were used exclusively for hauling logs (Meany 1935, 260). Soon after the turn of the century, the development of the high lead logging system (a method of dragging logs with one end suspended from a high cable attached to a lead or spar tree) permitted a faster, more efficient means to harvest large trees on rough, uneven terrain. The net result of these technological changes was that Olympic Peninsula tidewater lumbermen were no longer limited to logging in relatively narrow swaths at the Peninsula's outer edges but could gradually move their operations inland. According to author Murray Morgan, "Now it was possible to follow the receding tree line back into the foothills" (Morgan 1955, 129).

Logging railroads, just as the lumber industry itself, initiated in the Puget Sound area. Soon, however, they spread to inland sections of the Peninsula. By 1881, a logging railroad connecting Tenino and Olympia on the sound was in use. Historian Edmond Meany noted that in 1887, the Portland Oregonian newspaper reported that railroads "were being introduced everywhere as an aid to logging" (Meany 1935, 260). And by 1889, fifteen miles of logging railroad extended west of Shelton, and twelve miles of railroad ran west from Skookum Bay, both at the southern end of the Peninsula. While the average length of rail was twelve miles in the early days of railroad logging, one northern mill hauled logs forty to sixty miles by rail. Soon after the turn of the century, in the Douglas fir region of the Pacific Northwest, over 1,000 miles of rails, equipped with 323 steam locomotives (primarily the Shay, Climax and the Heisler) were in use (Meany 1935, 260-63).

Often with the assistance of rail lines, logging operations, both large and small, gradually began establishing logging camps and small mills between Hood Canal and Grays Harbor along the base of the Olympic Peninsula and on rolling foothills across the north end of the Peninsula. Rivers or rails (usually constructed along river valleys) provided a vital means for moving logs to mills or markets. Around the turn of the century, and shortly after, inland lumbermen conducted operations around the lower Dungeness Valley, north of Blue Mountain, and in the area of the Twin, Lyre, Little and lower Elwha Rivers and the Indian and Dry Creek drainages, all south and west of Port Angeles. At the southern base of the Peninsula, inroads were made north up the Hoquiam, Wiskah, Wynoochee and Satsop Rivers. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, young, yet rapidly expanding lumber companies, established lumber operations on the Peninsula: Merrill and Ring Co. at Pysht, Bloedel-Donovan at Beaver (both on the north Peninsula) and Rainier Pulp and Paper Co. at Shelton near the southern end of Puget Sound.

Dodwell-Rixon Survey. In 1897 the Olympic Forest Reserve was created. This action closed to entry and private acquisition an area of over two million acres encompassing nearly all of the Olympic Mountain range and roughly two-thirds of the entire Olympic Peninsula. One year later geographer Henry Gannett directed Arthur Dodwell and Theodore Rixon, with a small team of men, to survey the entire reserve and assess its timber resources. Their findings published in 1902 Forest Conditions in the Olympic Forest Reserve critically analyzed ninety-seven townships on the Peninsula. Key among the Dodwell-Rixon findings was that only 10,289 acres, a total of sixteen square miles, were logged within the limits of the reserve. "It is only in the southern tier of townships that logging operations on any considerable scale have been carried on" (U.S. Department of the Interior 1902, 18), they noted, primarily along logging railroads extending from Shelton on Puget Sound into T. 21 N., R. 5 and 6 W., and in the upper valley of the Humptulips River. Apparently only minimal logging occurred at the north boundary of the reserve in T. 30 N., R. 9 W. in the vicinity of Lake Crescent (U.S. Department of the Interior 1902, 14-18). None of the logged areas mentioned in the Dodwell-Rixon report are presently located in Olympic National Park.

Echoing Lieutenant O'Neil's report to Congress in 1896, Dodwell and Rixon pronounced on the vast amount of timber in the Olympic Forest Reserve, "Taken as a whole this is the most heavily forested region of Washington, and, with few exceptions, the most heavily forested region in the country" (U.S. Department of the Interior 1902, 14). In describing the distribution and extent of timber, Dodwell and Rixon noted, "the densest forests are found in townships near the Pacific coast, in the northwestern part of the reserve, and in the southern tier of townships." Of the total area examined, the survey leaders estimated that 2,883 square miles, or eighty-three percent of the reserve, was covered with merchantable timber (U.S. Department of the Interior 1902, 14). Dodwell and Rixon noted that, although very little of the reserve had been logged to date because major rivers were unsuitable for driving logs, railroads could be easily built up almost any of the rivers, particularly those on the west side of the reserve. They reported, "Taken as a whole, there is very little timber on the west slope of the reserve that can not easily be reached, and when the time comes when that quality of timber is marketable there are few reserves, if any, that can be logged so easily and thoroughly as the western slope of the Olympic Forest Reserve" (U.S. Department of the Interior 1902, 20). According to Dodwell and Rixon, only in the higher parts of the mountains, where the quality of the timber was poor, would railroad construction be difficult and expensive. They observed, "it will probably be many generations before the timber in these regions will be needed" (U.S. Department of the Interior 1902, 21).

|

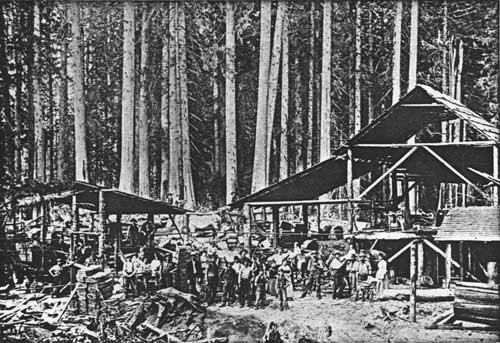

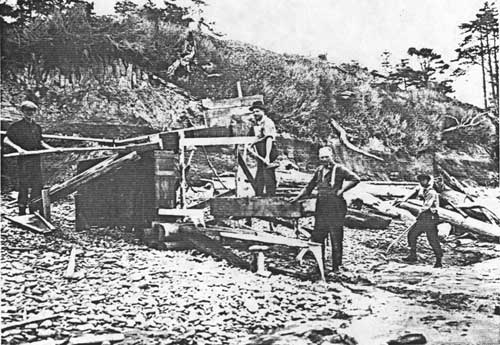

| The Colony Shingle Mill at Dry Creek, located about four miles north of the present park boundary, was typical of several milling operations located around the periphery of the Olympic Peninsula, in the late nineteenth century. (Courtesy of Olympic National Park) |

Escalation of the Logging Industry. Demand for wood products, however, steadily increased around the turn of the century. Lumbermen from the Great Lakes region, where timber stands were depleted, were attracted to the untapped virgin forests of western Washington, including those contained in the Olympic Forest Reserve. Even before the Dodwell-Rixon report was published in 1902, two presidential proclamations reduced the size of Olympic Forest Reserve by a total of over 700,000 acres, or twenty percent. Most of the eliminated lands were in the heavily forested western sections of the reserve from Ozette Lake south to the Jefferson County line. Many acres were bought up by lumber companies or acquired through Homestead Act entry claims or Timber and Stone Act claims, a purpose for which these two legislative acts ostensibly were not intended. Forty-two percent of the land eliminated from the reserve were Timber and Stone entries, and thirty-two percent original Homestead entries. Of these same eliminated lands, about a decade later, thirty-seven percent were owned by "speculators" and nineteen percent were owned by timber and logging companies (Rakeshaw 1955, 135; Younce 1978, 15). Some contemporary historians claim that land fraud by eager timber companies was not uncommon during this period (Younce 1978). Clearly, in the opening years of the twentieth century the timber resources of the Olympic Peninsula had not only been discovered but lumber industry technology and the apparent increased demand for forest products was encouraging increased utilization of timber resources on the Peninsula.

During the first quarter of the twentieth century, logging operations were conducted by numerous independent loggers on the Peninsula as well as those associated with such mills as the Carlsborg Mill, the Little River Logging Company, the Filion Mill Company, the Puget Sound Mill and Timber Company, Wallitner Mill and Logging Camp, Merrill and Ring, Robinson Logging Company, Goodyear Logging Company and Bloedel-Donovan. During the 1910s and 1920s lumbering extended across northern Clallam County from the Dungeness River on the east, to Sekiu and Sappho on the west. Logging railroads and railroad spurs formed an integral part of many logging operations and reached as far south as Little River, the Indian River Valley, Lake Sutherland (all at the northern boundary of Olympic National Park) and to Piedmont on Lake Crescent, now inside the Park boundary (Harper 1971c, 402; Harper 1971d, 397; Hall 1971, 421; Critchfield 1971, 575, 580; PADN 1977, 22 September).

Spruce Production Division. The advent of World War I suddenly placed great demands on the forests of the north Peninsula, in particular the spruce forests. In response to the European allied forces' urgent need for lightweight but strong Sitka spruce for the construction of wartime airplane wings, the United States War Department established the Spruce Production Division in 1917. Under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel Brice P. Disque, the Spruce Production Division initially assigned ten thousand soldiers from the U.S. Army Signal Corps to private logging firms, lumber mill operators and railroad construction contractors in both Washington and Oregon, in a fervent attempt to increase spruce production (U.S. Army and U.S. Spruce Production Corp. ca. 1919, 16). By the end of the year, twenty-five to thirty thousand soldiers located in 234 spruce division camps in the Northwest assisted nearly 100,000 civilians as loggers, mill workers and railroad laborers. Spruce Production Division soldiers cooperated with civilian contractors and laborers in constructing a total of thirteen logging railroads in Washington and Oregon, tapping the largest stands of Sitka spruce in the Northwest. On the Olympic Peninsula, Spruce Production Division workers began construction of three separate railroads in the spring and summer of 1918. Five miles of track were laid in the Quinault area and a similar length of track was laid near Pysht on the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The greatest stand of spruce forest on the Peninsula was reached by thirty-six miles of Spruce Production Division Railroad No. 1, extending from Disque Junction west of Port Angeles, west to the Hoko River area near Lake Plesant (Morgan 1955, 147). Approximately one-third of the thirty-six mile length of Spruce Division Railroad No. 1 right-of-way is now located inside the northern boundary of Olympic National Park.

The construction of Spruce Production Division Railroad No. 1 was among the greatest World War I engineering and labor efforts engaged in by the United States. To complete the thirty-six miles of track, the longest of all thirteen Spruce Production Division railroads, the contracting firm, Siems, Carey—H. S. Kerbaugh Corporation, employed 8,000 men (half of whom were soldiers) to work seven days a week, night and day. Typically inclement weather conditions often hampered construction work. Rugged terrain, unstable soil and dense forests along the projected route presented even greater difficulties. Along steep and rocky sections of the north shoreline of Lake Crescent, considerable blasting was required to clear a sufficiently wide right-of-way. The only two tunnels in the entire length of the Spruce Production Division Railroad No. 1 were bored through solid rock at two locations on Lake Crescent. In addition, certain shoreline sections required heavy ballasting and cribbing to create a stable, flat path for laying the rail. Further to the west, dense stands of timber and underbrush necessitated time-consuming, rigorous logging operations to clear for the railroad right-of-way. The enormous outlay of human power, materials and equipment, and the sometimes expensive acquisition of a 100 foot right-of-way, cost the U.S. government nearly $30,000 per mile. Spruce division Railroad No. 1 was the most expensive railroad per mile ever built to date. It was also the fastest built railroad, constructed seventy-five percent faster than any railroad previously laid in the United States. Fourteen months after initial construction work began in July 1917, thirty-six miles of main line track and various lengths of sidings and graded paths for spur lines were completed ahead of schedule. Just as the last rail was laid near Lake Pleasant on 30 November 1918, the armistice ending World War I was signed. Ironically, with all its great engineering and labor accomplishments, Spruce Production Division Railroad No. 1 hauled not a single log for the wartime effort (Harvey 1983).

|

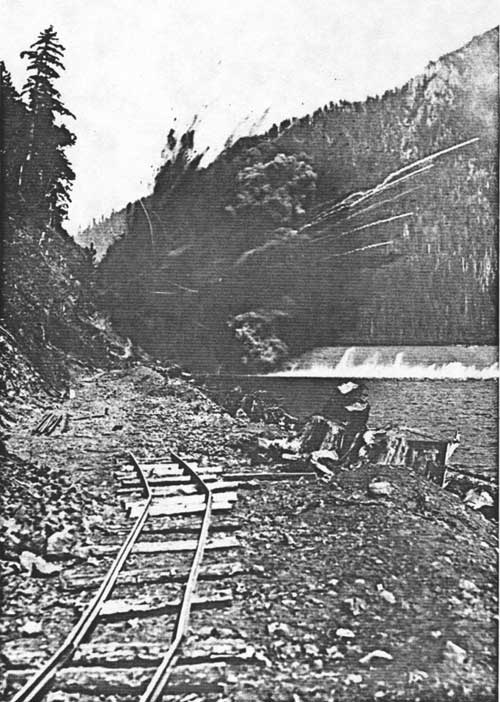

| In 1918, a contingent of the U.S. Army Spruce Production Division labored to construct a railroad on the north shore of Lake Crescent. (Photo by A. Curtis, courtesy of Washington State Historical Society) |

|

| Dynamite, used liberally by the U.S. Army Spruce Railroad Production Division to construct the Spruce Railroad No. 1, blasted through rock on the north shore of Lake Crescent, in 1917. (Photo by A. Curtis, courtesy of Washington State Historical Society) |

Of all Spruce Production Division railroads Spruce Railroad No. 1 was one of only three that remained intact after World War I. During the 1920s and 1930s, Spruce Railroad No. 1 fell to the ownership of two different private corporations. However, competition from neighboring logging railroads stifled the full utilization of the Spruce Railroad No. 1 (renamed the Clallam County Railroad) as a logging railroad. During World War II, the first wartime shipment of logs was via the railroad. Following the war, financial difficulties prevented necessary repairs and renovation to the line. In 1951 a fire originating along the Clallam County Railroad led to costly lawsuits eventually forcing it into receivership. Finally in 1954 the original Spruce Production Division Railroad No. 1 was abandoned. Eventually the rails were torn up for scrap (Harvey 1983). Today, approximately five miles of the Spruce right-of-way is a maintained hiking trail in Olympic National Park. One nearly intact tunnel, several sections of reinforcing embankment cribbing and random, sometimes overgrown sections of rail and railroad ties, remain testament to World War I and later logging efforts in the expansive stands of timber in western Clallam County.

Logging on Public Land. Few other activities associated with logging in Olympic National Park can be as easily identified and located as those of the Spruce Production Division logging railroad. Records of small, private, independent loggers and larger logging or mill companies dating from the 1920s and 1930s are difficult and time-consuming to trace. Many early lumber companies are no longer in existence or have been bought and sold on numerous occasions. In addition, government records pertaining to logging operations on public lands are destroyed, inaccessible or incomplete and leave only a broken historical record pertaining to the parties and locations involved in logging activities inside the present Olympic National Park boundary. The story of logging in Olympic National Park can only be pieced together by reviewing the general land management policies of the various administering agencies, legislative documents, articles and books written about logging activities on the Peninsula and scanty, existing correspondence and reports of government officials.

In 1905 administration of Olympic Forest Reserve, soon after renamed Mount Olympus National Monument, became the responsibility of the National Forest Service in the Department of Agriculture. With knowledge of European methods of forestry, the small cadre of early Forest Service policymakers at first engaged in studying existing conditions on U.S. forest reserves, with a view to application of European timber management principles. From the initial creation of the Forest Service the aim of the organization was "to introduce rapidly the idea of the greatest use [of forested lands] to the largest number" (Fromme 1913, 9). As Olympic Forest Supervisor R. L. Fromme explained in 1913: "With the application of this idea of wise use of the national timber resources, it was but a short time until the very inappropriate and misleading 'reserve' was dropped for the adoption of the name national forest, which means development and use just as rapidly as local conditions and needs permit and justify, and in such a manner as to prevent waste, attain the greatest benefit for all the people, and make such benefits just as far as possible perpetual" (Fromme 1913, 9).

Supervisor Fromme gave some indication that logging activity in the Mount Olympus National Monument was minimal in 1913 "because of the inaccessibility of the vast majority of this timber as compared with large holdings of private timber on bordering lands near tidewater" (Fromme 1913, 10). However, when immense stands of timber on private holdings were depleted, it was expected that the expansive reserves of "mature" and "over-mature" timber on monument land would be drawn upon for a permanent supply of forest products (Burns 1911, 7; Fromme 1913, 10).

From 1905 to 1933 administration of Mount Olympus National Monument (occupying only the central and eastern portions of the present Olympic National Park) remained under the jurisdiction of the National Forest Service. Timber management policies and specific plans for Olympic National Forest, which circled the monument, often did not differentiate between forest lands and monument lands. As early as 1911, one timber sale was made within the monument with others planned in the near future. In 1915, as impending wartime demands for airplane and ship timber increased, the size of Mount Olympus National Monument was reduced by approximately one-half. That year Forest Service foresters implemented a timber management plan designed to inventory the timber stand on both forest and monument lands. The plan noted that the "chief function of the National Forest is the furnishing of a continuous supply of timber." The policy of full utilization of all Olympic National Forest timber was again duplicated in 1923 and 1924 Forest Service timber management plans for the Olympics (Twight 1971, 46-47, 50, 55).

In the mid to late 1920s logging of Forest Service timber was getting underway. The Soleduck River Valley (slightly west of Olympic National Park), was the site of several timber sales and logging operations conducted by the Irving-Hartley Logging Company (renamed the Crescent Logging Company), Bloedel-Donovan and Merrill and Ring logging companies. A longtime Forest Service employee, Sanford Floe, recalled, "that the combined cut of these three large railroad logging outfits was about 500 million board feet a year for the next several years, all shipped to upsound mills as there were no sawmills operating in Port Angeles" (NFS ONF 1959, 14 May). In 1946 Clarence Adams, administrative assistant for Olympic National Forest, noted that from 1925 to 1945 the Crescent Logging Company and Bloedel-Donovan Lumber Company "cut the fir type and private holdings in the Soleduck and North Calawah drainages" (NFS ONF 1946, 14 May). In the meantime, intensive logging by lumber companies from the Aberdeen and Hoquiam area proceeded to cut extensively on the south Peninsula north toward the southern national forest boundary. Demands for allocation of timber on the west side of the forest in the Bogachiel, Hoh and Queets drainages were presented to the Forest Service in the late 1920s. Lumber companies from around the Olympic Peninsula, including Bloedel-Donovan and Merrill and Ring with timber interests on the north Peninsula, the Simpson Timber Company of Shelton in the southeast, and various logging interests in the southwestern Grays Harbor communities, all vied for exclusive privileges to log the timber stands on the west side of Olympic National Forest. Despite this exerted pressure, the Forest Service decided to withhold timber from sale in the west Olympics pending the construction of a common carrier railroad (Twight 1971, 60-61). Although plans for a new rail line to tap the "wilderness of giant trees and dense undergrowth" in the western Olympic region were announced by the Union Pacific and Northern Pacific Railroads in the spring of 1930, the project never materialized (Fetterolf 1930b, 5).

Inaccessibility to the valuable stands of timber in the west side drainages continued into the early 1930s. However, an awareness of the potential economic significance of this heavily forested area in no way diminished. In response to a letter written by National Park Service Director Horace Albright in 1931 suggesting the creation of a national park on the Olympic Peninsula, Chief Forester Major R. Y. Stuart contended that timber stands under their jurisdiction were "not now of economic significance because of inaccessibility but destined eventually to have significance as other more accessible supplies are exhausted" (Twight 1971, 64).

It was not railroads, but roads, that began to open up the west side to the timber industry. Although passable roads were extended across the south and north ends of the Peninsula in the 1920s, it was not until 1931 that the Olympic Mountains were completely encircled by a 375 mile loop road (present-day U.S. Highway 101). Newspapers throughout western Washington heralded the event as the opening of the "last frontier." In an article announcing the upcoming dedication ceremony at Kalaloch on the Pacific coast, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer noted, "while much of the northern part of the route has been denuded of trees by logging operations, forests of jungle-like denseness line a large part of the sections now to be opened" (Seattle PI 1931, 28 June). With the introduction of the logging truck on the West Coast (as early as the late 1910s) and the completion of the Peninsula loop highway, access to the much sought-after stands of timber on the western slope of the Olympic Mountains was no longer a distant hope but a near reality. Longtime, west side Hoh River resident, Lena Fletcher, commented that although small timber harvests were undertaken by way of the ocean, "there was no real logging in the Hoh valley until after U.S. Highway 101 came through" (Fletcher 1966, 224).

|

| Logging on the Peninsula was advanced by logging trucks such as the one pictured here in the late 1910s. New primitive roads provided access to untouched strands of timber, and gradually logging operations moved further inland. (Courtesy of Olympic National Park) |

Timber accessibility, however, was not the only determinant to logging activity on Olympic Peninsula Forest Service administered lands. The nation's Great Depression brought about changes in the administration of Olympic National Forest and Mount Olympus National Monument that had significant repercussions for Peninsula lumbering interests. In an attempt to encourage the nation's recovery from economic depression the U.S. Congress, in the early 1930s, approved legislation for the reorganization of certain conservation related agencies and for the activation of public works projects (Twight 1971, 65-66). As a result, two things occurred that affected logging on Olympic federal land: 1) on 10 June 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt issued an Executive Order transferring all national monuments, including Mount Olympus National Monument, to the National Park Service; and 2) works project groups under the Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) Program and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) were put to work improving or extending several roads on Forest Service land. These roads invariably connected with the new Olympic Peninsula loop highway. By the mid 1930s, stub roads, built by the Forest Service, extended up the Elwha, Soleduck, Hoh, Quinault, Dosewallips and Duckabush River Valleys to within ten or fifteen miles of the Monument (U.S. Congress 1936, 165). Thus, while improved or new stub roads on Olympic National Forest land provided greater access to yet untapped forested lands, the monument lands, under the administration of the National Park Service, were shielded from active lumber industry development.

Beginning in 1935, a series of bills were introduced in Congress proposing the creation of an Olympic National Park and suggesting various boundaries. Studies conducted on the different proposed boundaries of the Park, along with public testimony given by both opponents and proponents of the differing Park proposals, reveal that the most extensively logged areas, to date, had occurred in the west side drainages of the Bogachiel, Hoh, Queets and Quinault Rivers on Olympic National Forest lands. A 1936 report on the probable effects of the proposed enlargement of Mount Olympus national monument, written by National Park Service Forester Walter Horning, indicated that a total of 42,021 acres of National Forest land has been logged with no areas logged on the existing National Monument. Forester Horning also noted that, although selective cutting of individual large trees was tried in certain sections of the Peninsula, logging on all the National Forest Service lands involved clear-cutting (removal of all trees on a parcel of land) in order to minimize costs (NPS OLYM 1936, 10, 77-80). At 1936 public hearings before the House Committee on the Public Lands discussing the creation of Olympic National Park, testimonies given by numerous individuals indicated that logging on or near Forest Service lands had occurred in the vicinity of Quinault Lake and on privately owned lands west of Lake Crescent, fed by the old Spruce Production Division Railroad (U.S Congress 1936, 14, 178, 211-12). Forester Horning's 1936 report made specific recommendations for the immediate acquisition of the landholdings of Conwango Lumber Company and George Gund who owned parcels of speculative timber lands on the south shore of Lake Crescent near the west end of the lake (NPS OLYM 1936, 185).

Finally, after three years of lengthy public debate focused on the proper boundaries of a national park on the Peninsula, President Franklin Roosevelt signed into law a bill establishing a 682,000 acre Olympic National Park. The newly formed Park was more than double the size of Mount Olympus National Monument and included extensive forested lands on the north and west previously included in Olympic National Forest. A provision was attached to this bill allowing for additional expansion of the Park, by presidential proclamation, not to exceed a total of 892,000 acres. Less than two years later, Roosevelt added ten separate parcels of land totaling 187,411 acres, and expanded the Park in nearly all directions. In addition, Roosevelt authorized the acquisition of a strip of coastal land and a narrow corridor down the Queets River. Roosevelt's final Park addition came in 1943 with the acquisition of the Morse Creek drainage along the Park's northern boundary (Ingham 1955, 23-30).

Logging in Olympic National Park. With the creation of a large national park in 1938 and with subsequent additions, Olympic National Park in the early 1940s, included several logged off sections previously administered by the National Forest Service. The Park Service inherited, as well, Forest Service promises and provisions made for existing and future logging operations. Reference to newly acquired logged areas was made in some Park Service written records and correspondence dating from the early 1940s. In early 1940 National Park Service Director Arno Cammerer noted that logging operations were conducted on privately owned land within the Park west of Lake Crescent. Three miles west of Lake Crescent the Crescent Logging Company conducted timber operations on privately owned land (NPS OLYM 1940, 30 January). (Both these logged areas were subsequently acquired by the Park Service and are presently in Olympic National Park.)

In the same year National Park Service officials proceeded with negotiations to purchase logged parcels of land in the Queets Corridor area from the Polson Logging Company of Hoquiam, Washington (NPS OLYM 1940, 24 April). Olympic National Park Superintendent Preston Macy noted in an address given to the Western Forestry and Conservation Association in late 1940 that "a considerable portion of the land included within the Queets corridor had already been logged" (Ingham 1955, A-6). In 1944 Preston Macy signed a legal agreement with the Mayr Brothers Logging Company permitting the removal of timber along a proposed fifteen foot wide road right-of-way across the Queets Corridor acquisition land in the vicinity of Matheny Creek (NARS:RG 79 1944, 9 November). Logging activity in the Morse Creek drainage was apparently going on in the early 1940s and, in fact, prompted the acquisition of that addition by the National Park Service to protect the water supply of Port Angeles (Ingham 1955, 29).

|

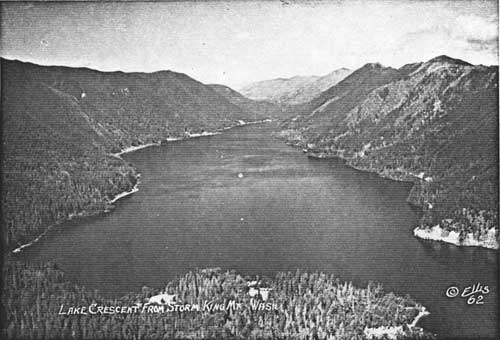

| Light patches on the sloping ridges on the right side of this 1940s photograph, indicate new growth on logged areas above the north shore of Lake Crescent. Barnes Point is in the lower foreground. (Courtesy of Ellis Studio and Post Card Co.) |

With the advent of World War II, following closely on the heels of the creation of and subsequent additions to Olympic National Park, tremendous pressure was put on the Park to allow logging of spruce and fir, particularly in the lower bottom lands of the Bogachiel, Hoh, Queets and Quinault Rivers. As early as November 1940, inventories of available Sitka spruce in the Pacific Northwest were conducted to determine the availability of spruce for manufacture into airplane stock. In a memorandum authored by private consultants C. A. Lyford and W. H. Thomas, it was noted that "of the estimated total of approximately ten billion feet of spruce in western Washington and western Oregon, 750 million feet is within present National Park boundaries, practically all of it in the Olympic National Park" (Gallison Collection 1940b). Also in late 1940, the National Park Service acting chief of forestry, in a memorandum to the National Park Service Director, stated that approximately 13.3 billion board feet of Sitka spruce were available on the west side of the Park; however he noted, "most of the better quality timber on the Bogachiel, Hoh, Queets and Quinault Rivers involves long hauls by truck to railroad—adversely affecting economic logging availability" (NPS OLYM 1940, 10 December). During the early 1940s, it was decided, in the interest of the war effort, to permit the sale of blowdown timber (trees blown over by heavy winds) on Finley Creek in the Quinault area. Finally, near the end of World War II, the "War Production Board officially intimated to the Department [of the Interior] that the demand [for spruce] had receded and the supply appeared sufficient to eliminate any necessity for timber from the Olympic National Park" (NARS:RG 79 ca. 1944a, n.d.).

In the decade following the war the process of acquiring privately owned land within Olympic National Park boundaries by condemnation or complicated land exchanges sometimes permitted or encouraged logging activity on Park land. Between 1942 and 1955, the Park Service pursued a program of exchanging salvable fallen or diseased timber for privately owned lands within the Park. Approximately 3,680 acres of private "inholdings" were acquired in this way (Ingham 1955, 30). Some privately owned lands acquired by condemnation resulted in litigations allowing owners to remove timber from their property over periods varying from fifteen to twenty years. In other instances timber trespasses occurred where private owners with land in the Park, or adjacent to it, logged. In 1954 Olympic National Park Superintendent Fred J. Overly, in summarizing his duties and responsibilities in a report to National Park Service Director Conrad Wirth, wrote: "Pressures will continue for selective logging of park timber. These pressures will probably increase with time as timber outside the park becomes more scarce, and will likely involve proposals for elimination of certain timbered areas from the park" (UW 1954, 3 December).

Mineral Exploitation

Early Reports of Mineral Wealth. For more than a century man has predicted and searched for mineral wealth on the Olympic Peninsula. Along with trappers and hunters, little known sections of the rugged interior foothills and mountains were first visited by zealous, hopeful mining prospectors. Perhaps stirred by visions of rich strikes equal to those that induced the great gold rush in California and southern Oregon in the late 1840s and early 1850s, gold was the first sought after mineral on the Peninsula. But before the turn of the century, random reports claimed the presence of the widest assortment of metallic and nonmetallic minerals scattered around the Peninsula. In addition to gold, silver, iron, copper, manganese, tin, coal, oil, sandstone, granite and marble were said to exist. Scientific records and documentation of mining activity and exact locations before 1900 are scanty. Thus, a heavy reliance must be placed on the often colorful yet sometimes exaggerated and vague hearsay reports, or speculative accounts found in contemporary newspapers and expedition accounts.

During the period of early settlement in Washington Territory, James Swan, resident of Shoalwater Bay on the Pacific Ocean (now Willapa Bay) between 1850 and 1855, was among the first to make note of Indian accounts of gold in the mountains of the interior (Swan [18571 1977, 251). After alleged discoveries of gold on tributary streams of the Chehalis River (at the extreme southern end of the Peninsula) by crew members of the ship Leonidas, Swan reported in an 1861 issue of the Washington Standard newspaper that "wherever the streams have been examined the color of gold is found (Hult [1954] 1971, 149)." An 1877 article in the Puget Sound Weekly Argus entitled "Gold in the Olympic Range" not only reported the 1859 gold discovery of the Leonidas crew members but told of a recent gold find on Morse Creek near Port Angeles where old California miners were presently at work. Joseph O'Neil, while leading his first expedition into the Olympic interior in 1885, learned that several years earlier, Captain John W. White had supposedly discovered gold on his ranch near the mouth of Ennis Creek, just east of Port Angeles (Wood 1976, 17). In the vicinity of Lake Cushman, on the southeastern slopes of the Olympic Mountains, an experienced New Zealand miner and geologist was reportedly encouraged by the similarity in appearance between the gold-bearing district in New Zealand and the southern slope of the Olympic range. New Zealand miner, Mr. Hartley, reported to the Weekly Argus his find of a valuable deposit of iron ore and expressed his opinion that the range was rich in minerals, including gold. With assurance the Argus proclaimed, "The evidence of mineral wealth in the Olympic group, and in fact in the foot hills from Hood's canal to Cape Flattery, is very positive; but as yet the whole region is a terra incognitio [sic]—no one has visited it or explored it, and no one can assert that it is not as rich as the richest gold fields of Australia or Cassiar" (Weekly Argus 1877, 16 March).

Just one year later, in 1878, indications of gold found on the Hood Canal induced a party of five, led by Melbourne Watkinson, to explore the North Fork Skokomish and Quinault Rivers region. Whether the Watkinson party actually did find any color of gold on their expedition is unclear. However, the trip's historian, Eldridge Morse, later recorded that the party found evidences of iron, silver and copper (Univ. of California 1880).

In addition to gold, the discovery of iron and copper was noted in several early publications. In 1871 an Olympia newspaper claimed that rich iron ore deposits were found near Lake Cushman (Washington Standard 1871, 28 January). By 1885 the low lying, early settled, agricultural Chimacum Valley (in the northeastern section of the Peninsula) gained a reputation for its rich deposits of iron ore. At Irondale on Port Townsend Bay, the Puget Sound Iron Company "expended about half a million dollars in preparation for manufacturing" in the mid 1880s (Report of the Secretary of the Interior 1885, 1096-1098). In 1885 Lieutenant Joseph O'Neil found strong indications of iron in the upper Ennis Creek drainage when his compass needle was deflected while he stood on a "mountain of magnetic iron" (Wood 1976, 22; U.S. Congress 1896, 18). Excitement about iron deposits in the Lake Cushman area renewed in 1888 and apparently aroused the interest of not only local residents but engaged the fantasies of speculators in San Francisco and New York by the early 1890s. After receiving glowing reports of mineral potential in the region from a commissioned mineralogist, the group of New York investors suddenly lost interest and the exploitive project quickly died (Overland 1981, 15-16).

The Lake Cushman area was the site of yet another metallic mineral discovery in 1888. In September of that year two local residents, J. D. Dow and A. H. Rose, found copper leads in the North Fork Skokomish River bottom, approximately four and one-half miles above Lake Cushman (before it was enlarged by damming). By the spring of 1890, the Mason County Mining and Development Company, presided over by Seattle resident F. H. Whitworth, was organized, and development of the mines pushed ahead rapidly. A trail to the mine from Hoodsport was quickly cut and graded, and two large camps were built. According to an 1890 issue of the Mason County Journal, in early August a "gang of men . . . [were] hard at work blasting and working out the rich red ore, gleaming with its yellow freight" (Mason County Journal 1890, 15 August). In addition to the shafts sunk by the Mason County Mining and Development Company that summer, fifteen other claims were located in the same general vicinity. A Grays Harbor company, headed by John S. Soule, controlled seven of these claims which were variously known as "Hoodsport," "Sheriff," "Mascot," "Olympic," "John Mac," "O. K.," and "Dakota" (Mason County Journal 1890, 15 August). More than a year later the "promising Cushman mines" had developed still further and at least three additional claims were located; "Eureka," "Skokomish," and "Mountain Boy." The Allyn Times newspaper of 1 October 1891, described each of the three cuts in detail and noted that amounts of both copper and iron ore were being produced. Harry Fisher, 1890 O'Neil expedition member, wrote in his journal of the presence of the mining camp northwest of Lake Cushman, where copper deposits were believed "better than any of the rich Alaska mines" (Wood 1976, 74). O'Neil, proceeding up the miner's trail with his party of men and mules upon arriving at the copper mines, directed expedition mining engineer and mineralogist Nelson Linsley to inspect the mines. Linsley found "free copper deposited in a formation of sandstone and slate, but apparently it was not present in great quantities. The Mason County Mining and Development Company continued their active promotion of the mines above Lake Cushman for several years before discontinuing operations (Wood 1976, 84-85, 404). Finally, in addition to the early occurrence of copper mining on the North Fork Skokomish River, a wide belt of copper was reportedly found on the Humptulips River (another eastern slope drainage) prior to 1891 (Seattle PI 1891, 1 January).

O'Neil and Gilman Accounts. Both 1889 and 1890 were active years for discovery and exploration of the vast "unknown" and "wild" interior of the Olympic Mountain range. Long known as terra incognita, several organized expeditions set out to penetrate this rugged, densely forested land of jagged and jumbled peaks to finally exfoliate mysteries of a country that captivated and awed man's imagination for years. The travels and exploration of two expedition teams, that of C. A. and S. C. Gilman and of Lieutenant Joseph P. O'Neil, were among the most widely publicized and well-documented of any at that time. More than other expeditions of the period, these two parties left behind a more complete and detailed description of the topography, vegetation, wildlife and geology of the country they explored. Both the Gilman and O'Neil parties reported on the presence and potential extent of minerals in the Olympic country.

In late 1889 and early 1890, ex-lieutenant governor of Minnesota, Charles A. Gilman, with his son Samuel C., completed two expeditions into the Peninsula interior. Reports of their findings, which appeared in Northwest newspapers and magazines, gave promising accounts of a variety and, in some cases, an abundance of minerals on the Peninsula. "Colors of gold," they noted, "are found in the beach sands and along several streams in the mountains. . . . Low grade silver and copper ore are found in good-sized veins in the mountains" (Gilman and Gilman 1896, 139), although comparatively little prospecting had been done due to their inaccessibility. Iron ore, the Gilmans reported, "was scattered promiscuously over the peninsula in limited quantities" (Gilman and Gilman 1896, 139). Near Port Townsend a deposit of limonite (an important ore of iron) had been worked for some time. They contested that "the traces of iron are so abundant and widespread that it would seem that there must be somewhere in the Peninsula extensive deposits of a pure and valuable ore" (Gilman and Gilman 1896, 139). Tin ore yielding a rich assay was found in paying quantities on the Skokomish River. The Gilmans discovered "coal float" on a number of streams on the Peninsula (Sunday Oregonian 1890, 25 May), and also found "small seams of very good coal crop out in several places in sandstone and shale." On the Strait of Juan de Fuca, between Clallam Bay and Pillar Point, the Gilmans reported the existence of an extensive deposit of coal extracted earlier by the Thorndyke coal mine. This mine "was said to have been one of the best coals found in Washington" (Gilman and Gilman 1896, 138, 189). In addition, the Gilmans noted some white and yellow banks of clay and "two very extensive croppings of elegant sandstone" on the western slope of the Peninsula (Sunday Oregonian 1890, 25 May).

The reports generated by the 1890 trans-Olympic expedition of Joseph O'Neil and his party of men (including mineralogist Nelson Linsley), although ambiguous at times, were generally less optimistic about the mineral resources of the Olympics. At the outset of the expedition O'Neil confidently asserted "there must be . . . great mineral wealth here, for gold has been found in the foothills as has also coal. . . . The formation of these mountains seems to speak plainly of mineral wealth" (Wood 1976, 41). However, O'Neil later summarily discounted his supposition that the geology of the mountains foretold of rich mineral deposits by stating that the country was "too youthful to have concealed about its person precious metals" (Wood 1976, 398) Not inclined to persuasion by unfounded speculation about the Olympics' mineral wealth, O'Neil reported that although gold had been found on Ennis Creek near Port Angeles and the Lilliwaup Creek on Hood Canal, these deposits were entirely placer. Although quartz abounded in the Quinault Valley, upon inspection O'Neil found it to be barren of gold veins. Although copper traces were observed by the O'Neil party in the Skokomish, Wynoochee, Wishkah and Humptulips Rivers, there had been, as yet, no favorable reports of the extent of this mineral. Although the O'Neil party found a thick vein of iron amidst the rugged mountains, it was almost inaccessible. And even though there had been many reports of coal in the Olympics, O'Neil himself had seen no specimens and was hard-pressed to pronounce on their extent or worth (U.S. Congress 1896, 18; Sunday Oregonian 1890, 19 October).

O'Neil's skepticism of the Olympic's great mineral wealth was shared by other expedition party members. Recounting the adventures of the 1890 expedition more than forty years later, Botanist Louis Henderson recalled once hearing the exasperated words of the party's mineralogist, Nelson Linsley, while the trip was in progress: "Curse this country! I have prospected all the mountains of the United States and I never saw one to equal this in difficulty of progression and at the same time in lack of any valuable minerals" (Henderson 1932). In 1897 after returning from a prospecting and exploring trip with R. H. Young, Fred J. Church, another 1890 O'Neil expedition member, echoed his party member's sentiments regarding the mineral potential of the Olympics, "Our trip into the Olympics was a disappointment as far as finding any traces of ore was concerned" (SI 1897, 17 July).

O'Neil recognized his shift in expectations of the Olympic Mountains' richness of mineral resources. Explaining his conversion from hopeful optimist to blatant skeptic, O'Neil candidly wrote:

The stories of the people about these mountains led one to believe there were vast deposits of mineral wealth, awaiting only the coming of a discoverer. I do not know but what this idea made me more anxious to explore this unknown wild than even the delight and adventures of a new country. But the provoking coolness of my chief mineralogist, with his invariable "nothing here but sandstone" or "nothing here but basalt" [with] every new range we would come to, at last dampened my ardor as prospector, but the wonderful beauties of the country increased my ardor as an explorer (Wood 1976, 49).

Prospecting Reports in the 1890s. Despite Joseph O'Neil's denouncements, inflated expectations of rich mineral strikes in the Olympics lured untold numbers of prospectors into the mountains throughout the 1890s. During the summer of 1890, O'Neil observed, "The mountains were infested with miners and it was no uncommon occurrence to meet three or four parties a day" (Sunday Oregonian 1890, 19 October) Local newspapers, in fact, seemed to never tire of expounding on the Olympics' mineral wealth. Numerous articles with such flamboyant titles as "Many Rich Mines," "The Promised Land," "Gold in the Olympic Mountains," and "Rich Strike in the Olympics" appeared in newspapers throughout the Pacific Northwest and, no doubt, abetted and perpetuated the continuous flow of prospectors into the mountains in the 1890s. Prospecting parties exploring primarily the north, east and south watersheds of the Olympics brought back endless reports of gold, silver, cinnabar, tin, coal, iron, copper and nonmetallic minerals such as granite and marble (Seattle PI 1890, 26 June, 16 July, 14 August). Although specific details of exact locations of mineral finds are noticeably absent from many newspaper accounts, journalists of the day seemed to delight in recounting glowing reports of overzealous prospectors.

A sampling of these newspaper stories recreates the tenor of speculation that surrounded the Olympic Mountains at that time. In 1890 two Alaskan miners returned to Port Townsend with specimens of copper from a mountain ledge fifteen miles from Hoodsport on the Hood Canal. Prospector James McCauley told reporters that the belt of ore located was reportedly six miles wide and "without a single exception the richest belt I have ever seen in my life. . . . I propose to let even the rich Alaska mines go and devote myself to the new discovery in the Olympics" (Mason County Journal 1890, 22 August). Three prospectors, DeFord, Buckley and Seamon, returned from the Quinault River in 1890 bearing specimens of gold. Confidently they reported, "paying quantities [of gold exist] when the bedrock of the river is reached" (Mason County Journal 1890, 2 May). Signs of copper, iron and silver were also found, prompting DeFord to assert that "some day when this part of Washington is no longer a terra incognita, the wealth of this locality will be one of the wonders of the world" (Mason County Journal 1890, 2 May). Later in the same month Paul Barnes, brother of Captain C. A. Barnes of the 1889-1890 Christy (Press) exploring party, returned from a trip into the interior mountains with reports of finding quantities of gold, coal and oil. "There is no question about the country being rich in gold," he told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. He continued, "I have found free gold in the mountains as far as I have penetrated and have picked up lumps of coal as big as my head. . . . Oil can be seen floating on the surface of the creeks and oozing out of the ground" (Seattle PI 1890, 22 May). In 1891 Barton Robinson of Chimacum began prospecting in the hills south of Port Angeles where he eventually found valuable specimens of copper and gold. Gold finds were also reported in the tributaries of the Dungeness and the west branch of the west fork of the Quilcene River during the 1890s (Mason County Journal 1897, 16 April). Although periodic skepticism about, and on rare occasions outright denial of, the Olympic Peninsula's mineral wealth crept into journalists' columns, reports of continued "strikes" kept appearing in local newspapers. In 1897 the discovery of gold and silver was reported in the Jupiter Hills near the foot of Mount Constance outside the eastern boundary of Olympic National Park (Mason County Journal 1897, 12 February). The same year a "quiet mining boom" in the vicinity of the Dosewallips River was sparked by C. E. Gordon's and F. R. Robinson's discovery of gold, silver and copper (Mason County Journal 1897, 20 August). Again in the same summer, James B. Nesbit and W. M. Metcalf identified a formation of rock extending up the Skokomish River from Lake Cushman which they believed showed evidences of abundant gold bearing quartz (Mason County Journal 1897, 1 October).

Newspaper accounts of mineral deposits in the 1890s, with their excited tenor and vague locational descriptions, wrapped the Olympic Mountains in an aura of mythical mystique. Much was left to the reader's imagination then as it is today. However, one thing seems evident: newspapers of the day were clearly engrossed in the subject of the Olympic Mountains' mineral resources, and they seemed eager to promote prospectors' claims of abundant mineral wealth. The reasons for this are perhaps numerous, but one article first appearing in an early 1897 edition of the Mining Herald is revealing:

The Port Townsend Leader is exerting commendable effort to bring the Olympic field to the attention of mining men. . . . All of the cities of the east side of the sound are making extraordinary efforts to have the reserves . . . opened for mineral settlements, but they are giving little attention to the Olympics and unless [Port] Townsend and [Port] Angeles come out and unitedly protest in favor of their local communities the Olympic reserve may continue to remain as it is much to the detriment of the future business interest[s] of Clallam and Jefferson counties (Mason County Journal 1897, 16 April).

Mining On Park Land. Olympic Forest Reserve, encompassing over two million acres, was established by presidential proclamation on 22 February 1897. Although there were many initial protests about the size of the reserve (and within five years the Reserve was reduced by approximately twenty percent), miners' interests were protected: prospecting was allowed on reserve lands. After the creation of Mount Olympus National Monument in 1909, however, mineral development was not permitted on monument lands. Between 1909 and 1915, alternative bills for the establishment of a "Mount Olympus National Park" allowing mining were introduced in Congress. Somewhat reminiscent of the 1890s, exhorbitant claims of the Olympic's great mineral wealth appeared in Peninsula newspapers. In 1911 when Secretary of the Interior Walter Fisher visited the Pacific Northwest, a delegation of Hoquiam residents made preparations to meet him "laden to the gunnels with samples of ores—gold, copper, iron other—and with things to prove that former President Roosevelt's bear and cougar reserve better would be opened to exploitation and development than fenced off as a beautiful fernery." In a word, this newspaper article concludes, "the Hoquiam folks are prepared to convince Mr. Fisher or his agent that the monument is one stupendous mineral belt, capable of adding millions to the world's wealth, instead of a moose pasture, as it has been pictured by those who locked it up" (UW 1911). From the north end of the Peninsula at Irondale The News quoted reports of Tax Commissioner M. J. Carrigan who claimed the existence of "a copper zone 15 miles wide and 35 miles long as rich as anything of the kind in the world. All around the Olympic Peninsula . . . are both oil and gas, while there is a continuous coal bed extending from the Strait of Juan de Fuca to the City of Olympia" (Ingham 1955, 9). Copper deposits on the Peninsula were the largest in the country and manganese was, thus far, found in no greater quantity anywhere in the world. "All these," Mr. Carrigan said, "are in the Monument and are not worth a cancelled postage stamp to anybody today" (Ingham 1955, 9).

Due to vigorous opposition by miners and others, Mount Olympus National Monument was reduced by approximately one-half in 1915. These eliminated lands consequently became part of the encircling Olympic National Forest which not only permitted, but encouraged, mining activity. Not until 1938 (with extensive additions through 1953) when a large national park was created from the national monument and much of the existing national forest, were mining activities gradually and finally phased out. Because of shifting boundaries and changing administrative policies governing mining on the Peninsula's public domain lands between 1897 and 1953, Olympic National Park has an albeit short, but rich mining history.

While the potential mineral wealth of the Olympic Peninsula instigated great speculation and stirred endless controversy and dispute, actual mining activity within the bounds of Olympic National Park can be verified through: government records of patented mining claims, geological investigations and reports and, in some instances, through the written or verbal accounts of those who prospected. Known prospecting within the interior portion of the Park occurred principally in the northern and southeastern sections of the Park. In these areas manganese, with amounts of copper and iron, were mined in commercial quantities. Several mineralogists' reports describing the occurrence of manganese deposits on the Peninsula include the Lake Crescent/Mount Angeles area on the north and the Lake Cushman/North Fork Skokomish River area on the southeast in a broad, arching belt lying on the outer slopes of the mountains on the north, south and east (Green 1945, 5). In the Olympic National Park Coastal Strip prospecting for gold, oil and natural gas was the most prevalent mining activity.

Elwha River Mining. An approximate thirty mile long swath of land on the northern side of the Park, between the west end of Lake Crescent and Deer Park, is included in the horseshoe-shaped mineralized belt encircling the lower slopes of the Olympic range. The earliest available account of mining in this northern section of Olympic National Park dates from the 1890s. In late 1897 or early 1898 Ward Sanders, arriving in the Elwha River Valley with his cousins, Will and Martin Humes, began prospecting for gold in a ledge about 325 feet above the Elwha River and west of Hurricane Hill. Although disappointed to learn that his claim did not have paying quantities of gold, he wrote in a letter to Eastern relatives, dated 6 March 1898, that the nearby "Hurricane hill mine has proved rich in copper (DNR, Maps and Surveys; NPS OLYM 1897-1911, 1934). During the same period, Arthur Dodwell and Theodore Rixon conducted a survey of the entire Forest Reserve and, likewise, mentioned mining activity in the Hurricane Ridge area (U.S. Department of the Interior 1902, 19). Government Land Office surveyors' 1905 notes mentioned that gold, silver and copper had been discovered in several places on the north slope of Mount Angeles (DNR Maps and Surveys). At about the same time M. J. Gregory began working a mine in the Little River watershed southwest of Mount Angeles. By 1917, Gregory successfully drove four tunnels into different ledges on the mountain slope ranging in length from forty feet to 210 feet. Specimens were reportedly assayed at eighty-two percent zinc with smaller quantities of gold, lead and copper (Olympic Leader 1917, 21 August; Webster 1917).

Little River/Hurricane Ridge Mining. During the next few years, several manganese claims were staked in the so-called Little River or Hurricane District located directly west of Mount Angeles. In 1934 Stephen H. Green, field engineer for the Washington State Division of Mines and Mining, recorded a total of twenty-six claims in the district lying at an elevation of 4,200 to 5,000 feet on what is now locally known as Hutton Ridge. At that time the "Broken Shovel," "Ella," "F & L," "Chappie Group," "Sunset," and "Skookum" claims had all been worked, and the assayed value of specimens suggested to Green that the Little River District had an extremely large potential tonnage of manganese. In Green's written evaluation of the Little River District claims he notes the existence of one cabin on "Whistler Flat" at elevation 3,200 feet. In 1934 the Little River claims were accessible only by foot or horseback (NPS OLYM 1934 November). Ten years later local interests requested the state to survey for a mine-to-market road between Black Diamond Road and the cluster of Little River District claims, but the cost was apparently prohibitive and the road was never built (NARS:RG 79 ca. 1944a, n.d.). As late as 1960, three Little River District claims were privately owned or leased; however, none of these prospects were producing ore (NPS OLYM 1960). Today, there is only one known valid claim in the Little River District (the "F & L" claim). Various claims still show evidence of digging or tunneling. One mining cabin still stands. The collapsed remains of another cabin is also in the area (Hughes 1983). To the west of the Little River District managanese deposits, Mineral Engineer Stephen Green noted the occurrence of manganese deposits in the Aurora Ridge area in 1945. The Bertha claim, about one and one-half miles west of Lizard Head Peak, was staked but apparently not producing at that time (Green 1945, 32).

|

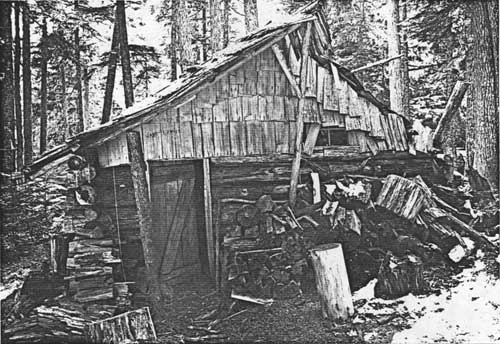

| A mining claim cabin still stands in 1983 in the Little River drainage of Olympic National Park. (Photo by M. Stupich, courtesy of National Park Service, Pacific Northwest Region) |

Lake Crescent Mining. At the west end of Lake Crescent several claims have been filed over the years. In 1923 Caroline Rixon, Theodore F. Rixon and Charles Anderson jointly located three claims, the Peggy M. lode, the Soleduck lode, and the Fairholme lodes near the western boundary of Olympic National Park about one and one-quarter miles west of Lake Crescent. In addition to drilling several tunnels and making several open cuts, more than half a dozen buildings were constructed on the claims including wood frame cabins, a "powder house," a blacksmith shop, a compressor house and an "ore bunker and tram-head house" (DNR Maps and Surveys). In the mid 1920s these three claims were accessible by a wagon road and the Spruce Production Division Railroad. Nineteen twenties reports claimed that the manganese ore produced was of a "very high grade" (DNR Maps and Surveys). The Peggy M., Soleduck and Fairholme lodes were presumably developed as the Crescent Mine, and operated under lease from the owners by Jamison and Peacock between 1924 and 1926. Albeit short but productive, tunneling at this mine prompted intensive prospecting in the entire area. During the mid 1920s, Peacock and Jamison themselves sent several men out to search for new deposits, but none compared in value to those at the Crescent Mine. Peacock and Jamison suspended operations in 1926. The Washington Manganese Corporation both owned and operated the mine until 1929 when the U.S. Bureau of Mines conducted deeper drilling operations at the site in conjunction with their strategic mineral investigation program. In 1941 the Sunshine Mining Company leased the operation and by 1945 produced more than 10,000 tons of ore. Drilling operations by the Sunshine Mining Company reached a depth of 950 feet. According to a 1945 report on manganese deposits on the Olympic Peninsula, the Crescent Mine had the "only deposit on the peninsula from which production of any considerable economic significance has so far been obtained" (Green 1945, 30-31). In 1960 the Crescent Mine, then owned by Theodore F. Rixon, Roy D. Rogers, Katherine S. Morgenroth and Robert E. Hedman, was still producing; 46,079 tons were extracted from the mine in that year (NPS OLYM 1960; PAEN 1940, 10 February). Today, operations at the Crescent Mine have ceased. Two readily visible tunnels, mining tailings and three or four collapsed and deteriorating buildings are the only remaining evidence of the once active, robust manganese mining operation (Hughes 1983).

Three other mining claims at the west end of Lake Crescent within the Olympic National Park north boundary were recorded in 1945 by Mining Engineer Stephen Green: the Peggy claim, the Daisy claims and the adjoining Daddy and Mother claims. Their years or amounts of production are not known and, by 1960, all three claims were either invalid or inactive (Green 1945, 31-32; NPS OLYM 1960, 76).

North Fork Skokomish Mining. One of the earliest and continuously prospected metallic mining areas on the Olympic Peninsula is located in the southeastern section of the Peninsula's horseshoe-shaped mineralized belt and is inside Olympic National Park boundaries. Robert Keatts, former Olympic National Park employee gives a well researched, detailed account of mining in his Mining on the North Fork Skokomish River booklet, published in 1982 by the Mason County Historical Society (Keatts 1982).

As early as 1871, the Washington Standard newspaper reported the presence of rich iron deposits in the Lake Cushman area, and by 1880 the first discovery of manganese on the Peninsula was found in the same area (Washington Standard 1871, 28 January; Green 1945, 6). Near the inlet of the North Fork Skokomish River in present-day Lake Cushman, the Mason County Mining and Development Company and a Grays Harbor company developed iron and copper mining operations in the late 1880s and early 1890s. In the 1890s the known existence of copper and iron attracted numerous prospectors to the Lake Cushman area where the "promising Cushman mines" were widely publicized by Peninsula newspapers. Members of the 1890 O'Neil expedition traveled along sections of a miner's trail above Lake Cushman and visited a miner's camp north of the lake. [Additional information about early Lake Cushman mining activity is found earlier in this chapter.]

Before Joseph O'Neil entered the mountains in 1890 by way of Lake Cushman, prospectors staked claims near the mouth of Seven Stream on the North Fork Skokomish River several miles above Lake Cushman. Known as the Darky Mine, the claims in the vicinity were worked by Blacks for many years. Smith Keller, Joseph Moss and George Thomas were among the most active in the mining venture. (In the 1940s the Darky Mine was also referred to as the Smith Keller or Lucky Wednesday Mine.) Although the value of mineral ore at the Darky Mine was apparently negligible, Keller, Moss and Thomas returned to their mine each summer and grubstaked for several weeks. Smith Keller with his partners presumably established claim to the Smith Mine at the headwaters of the North Fork Skokomish River in 1914. Longtime resident of the area and former Forest Service employee Andy Scott recalls the Darky Mine operators:

The colored fellers had their mine just across the creek from Big Log. They had a log cabin in there and I used to go up there and visit with them fellers. You know them son of a guns—they were always broke. Never had any money. They would come clear down to Staircase and bum me for food and want me to feed em. They were mining for manganese. . . . The Negroes used to go to Seattle in the winter and bum around and get somebody to stake them for the next year. They maybe would raise a thousand bucks or so in the winter. But they did that every year (NPS OLYM 1975, 18 April).

In 1935 and 1936 Joseph Moss was one of six men collectively referred to as the North Fork Mining Company that filed seventeen claims in the vicinity of the mouth of Nine Stream Creek (UW ca. 1936). In the mid 1970s little more than scattered pieces of milled lumber and overgrown tailings remained to identify the site of the Darky Mine.

|

| The mining tailings from the Black and White Mine remain as a testament to the perserving efforts of hard rock miners who sought to extract "paying" quantities of manganese and copper from the mountain side above the North Fork Skokomish River. Recent fire destroyed timber in the area. (Photo by R. Keatts, courtesy of Robert Keatts) |

Of the many mining ventures in the North Fork Skokomish area, the Black and White Mine has a long and convoluted history. Located in Olympic National Park about two miles east of the North Fork Skokomish at an elevation of approximately 4,000 feet, two claims were originally staked by Wilhelm F. Nelson in 1907. That same year Nelson's Kuger (Cougar) claim and Three Friends lode claim was joined by the Three-in-One and the Peerless lode claims of Nels C. Christiansen. The Arkansas Traveler lode claim filed by George B. Conaway and Frank B. Standard in the fall of 1907 completed the group of five original claims that comprised the Black and White Mine (Keatts 1982, 14). For the first several years copper was the principal mineral prospected. Located below a rocky ridge high above the North Fork Skokomish River, transporting the mineral ore was an early problem. In 1912 the Olympian Copper Company (presumably made up of several individuals with mining interests at the Black and White Mine) requested permission from the Forest Service to use downed timber in the area for constructing a six to eight mile flume to transport ore from the mine. Although the Forest Service was agreeable to the plan, the flume was apparently never built (NFS ONF 1912, 22 July, 23 July, 6 August). Reportedly, in 1915, five tons of ore somehow were shipped to the Tacoma Smelter where quantities of copper, iron and silver were extracted. And around 1918, when the presence of copper was first recognized (Green 1945, 40), 100 tons of ore were shipped to the Bilrowe Alloys Company in Tacoma. Lack of a feasible, economical means of transportation, however, continued to present difficulties for the claimholders. Possibly for that reason, the Black and White Mine was put up for sale in 1919. The sales promotion emphasized the potentially easy access to the mine site and offered, in addition to the ore veins contained on the five claims, "one cabin, tools such as picks, shovels, cant hooks, saws, forge and a number of smaller tools, also about one hundred pounds of spikes, all of which are on the property ready for mining operations or construction work, for the sum of $150,000" (Keatts 1982, 16). The sale was never made. A trail remained the only access. While actual mining continued primarily on the Three Friends claim, five additional claims were filed over the years (Keatts 1982, 14-17).

In the mid 1940s development work at the Black and White Mine consisted of a 200 foot tunnel, a forty foot shaft and several pits and open cuts (Green 1945, 40). During the 1940s, Olympic Mines, Incorporated, claimed ownership of the mine (Hunting 1956a, 61). W. H. Anderson filed for performance of annual labor assessment between 1950 and 1964, followed by W. R. Anderson. Since 1965, no filing procedures have been completed by claimants. During the 1950s and 1960s, hikers used a miner's cabin at the Black and White Mine as a shelter. In 1964 Olympic National Park Superintendent John E. Doerr requested permission to remove it from the Park's Historic Structures Inventory (NPS OLYM 1964, 17 March). By the mid 1970s the cabin was in collapsed condition and by the early 1980s only the foundation logs remained. Today, a series of barren mining tailings, pits, open cuts and a tunnel are testimony to an earlier era of prospecting at Black and White Mine. As a result of a fire that ravaged the area in 1936, the remains of mining activity at this site are perhaps the most visually impressive of all the hard rock mining sites in the Park.