|

Oregon National Historic Trail ID-KS-MO-NE-OR-WA-WY |

|

NPS photo | |

Oregon!

The very word evoked visions of paradise. Towering trees. Lush valleys with rich

soil. Land of unlimited opportunity. Between 1840 and 1869 those visions lured

over 500,000 pioneers west to fulfill their dreams and a nation's destiny. Their

2,000-mile route is known today as the Oregon Trail.

Beginning—the Gateway West

Long before it was a wagon road, the Oregon Trail was part of an ancient network of Indian footpaths and animal trails that crisscrossed the West. In the early 1800s British, French, and American fur trappers followed those paths as they hunted for beaver, whose fur was in demand for stylish hats in Europe. In 1812 fur trader Robert Stuart and six companions, following an Indian trace in today's Wyoming, made an important discovery—a wide pass, 7,550 feet in elevation, across the Continental Divide. South Pass made overland travel with ox-drawn wagons possible, and it became the gateway to the West. In 1851 Amelia Hadley wrote: "There we saw the far famed south pass, but did not see it until we had passed it for all the time I was looking for some narrow place ... but was disappointed."

Freight wagons began to beat a track along the Platte River and South Pass in the 1820s and 1830s. These fur brigades carried supplies from St. Louis to the fur trappers' annual Rendezvous in the Green River country of today's Wyoming and Utah. Returning caravans hauled pressed beaver pelts to Missouri. This "fur trace," wheel tracks along the Platte and through the Rockies, began the Oregon Trail. Christian missionaries eager to convert Indians took advantage of the fur traffic between East and West, joining caravans for safe passage. Missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and Henry and Eliza Spalding joined the 1836 fur brigade to Wyoming, then headed to Oregon Country. Narcissa and Eliza were the first white women to cross the continent on what became the Oregon Trail.

As the 1830s ended, so did the supply of beaver. The last mule cart and missionary brigade headed up the trace toward the final Rendezvous in April 1840—accompanied by Joel Walker, his family, and two wagons. From the Rendezvous, the Walkers joined trappers and headed to Fort Hall, a trading post on the Snake River in today's Idaho. They sold their wagons and continued west with a fur company pack train bound for Fort Vancouver.

Joel and Mary Walker and their four children arrived in Oregon's Willamette Valley in mid-September—and Mary gave birth to a baby four months later. They proved that families could make the overland trip, opening the Oregon Trail for other pioneer families.

WILLIAM HENRY JACKSON (1843-1942)

Jackson sketched hundreds of scenes while working as a freight wagon bullwhacker on the Oregon Trail in 1866; these became the primary source for his paintings. Jackson was the first to photograph western wonders, like Yellowstone in 1871. Drawing on his early encounters with Indians and settlers, Jackson painted these six Trail scenes in his 80s, revisiting each site to ensure their accuracy.ROCK CREEK STATION, NEBRASKA. Emigrants rested and stocked up at this Trail milepost before heading west. It also served as a Pony Express station.

UPPER CROSSING OF THE SOUTH PLATTE RIVER, NEBRASKA. After crossing the river, emigrants faced their first major grade, California Hill, a climb of 240 feet in about 1½ miles. Trail ruts are plainly visible on the hill today.

SCOTTS BLUFF, NEBRASKA. Indians named this landmark Me-a-pa-te—hill that is hard to go around. Travelers could see this 800-foot bluff towering over the prairie several days before reaching it.

INDEPENDENCE ROCK, WYOMING. Thousands of pioneers chiseled their names into this rock that looked like a "huge whale" from a distance.

THREE ISLAND CROSSING, IDAHO. Travelers faced a tough decision here: risk crossing the swift, deep Snake River or endure the hot, rocky route along the river's south bank. Pioneers' diaries recount the horrors of failed crossings—wagons, livestock, and people swept away. A safe crossing meant clean water and more grass for livestock.

OREGON, AT LAST! In 1845 the Barlow party opened the first overland route over the Cascades, traversing the south side of Mount Hood. The trip was over when the wagon trains reached the end of the Trail at Oregon City.

Why Go West?

Economic depressions in 1837 and 1841 left desperate farmers and businessmen looking for new opportunities. Politicians urged people to go West, where a stronger American presence might help wrest the disputed Pacific Northwest from British control. Missionaries described the land's fertility and promoted its development potential. A growing spirit of national pride and the idea of Manifest Destiny—that God intended the United States to stretch from coast to coast—made it seem a citizen's patriotic duty to go West. The fur trade had crashed, leaving unemployed trappers looking for new work as trail guides.

In early 1841 the first emigrant wagon train set out from Independence, Mo. The party of about 80 men, women, and children joined guide Thomas Fitzpatrick. He led them up the Little Blue River across northeastern Kansas, following the old fur trace along the Platte River. The wagons rumbled by Chimney Rock's spire and Scotts Bluff's prominence. On the Sweetwater River they passed by Independence Rock and the cleft called Devil's Gate, finally starting up a long, wide, gentle grade—South Pass! The emigrants were on the Pacific side before they realized they had crossed the Continental Divide.

The travelers separated at Soda Springs. The core, the Bidwell-Bartleson Party, headed to California, while the others followed Fitzpatrick to Fort Hall. The Oregon-bound travelers hired a new guide to pilot them along the Snake River and over the Blue Mountains, and Indians guided them down the Columbia River to Willamette Valley. This route became the Oregon Trail corridor.

By 1845 Americans outnumbered the British, and in 1846 Britain surrendered its territorial claim and withdrew to Canada. In 1850 Congress passed the Donation Land Act, offering 160 acres of free Oregon land to white males or half-Indian settlers and another 160 acres to their wives. Travel (and weddings) boomed as settlers rushed to stake claims before the law expired in 1854.

At first Indians helped emigrants, but things changed as they discovered that the "free land" offered to whites was their ancestral territory. By the mid- to late 1800s settlers lay claim to most tribal lands.

From Path to Highway

For emigrants the lure of land and opportunity outweighed personal sacrifices and the risks of long-distance wagon travel. It meant backbreaking toil and the possibility of death from accident, violence, or disease. Even so, traffic on the trail kept growing. Just 10 years after the Walkers followed the old fur trace, a well-beaten road sprawled across the prairie. Traffic was not just westbound. Discouraged pioneers turned around; successful settlers returned to persuade family and friends to join them in Oregon; and supply wagons rumbled to and from military forts.

This highway was not straight, smooth, or direct. It followed streams, wound around hills, and avoided deep sand. On steep slopes travelers lugged wagons up with ropes and stuck poles in wheel spokes to brake them on the way down. At dangerous river crossings, they floated wagons on makeshift ferries. Worst was The Dalles—a fearsome stretch of Columbia River rapids—where many pioneers floating on rafts perished close to their final destination. In 1846 the Barlow Toll Road provided a safer route, one of many cutoffs developed between jumping-off places in Missouri and trail's end at Oregon City, Ore.

Indians and Emigrants

In the first decade of Oregon Trail travel, relationships between Indians and emigrants were generally cooperative. Tribes provided fresh meat, guided travelers across rivers, and helped search for lost livestock. Most emigrants returned these favors with kindness. But tensions grew when the stream of wagons increased in 1849 in response to the California gold strikes. Livestock trampled native plants, and emigrants slaughtered buffalo herds that tribes needed for sustenance. Some Indians tried to collect payment for passage across tribal lands, but most emigrants regarded these requests as arrogant demands for tribute.

Relations deteriorated by the late 1850s. Indians killed travelers and emigrants killed Indians. In the Oregon Territory farming, mining, and logging destroyed salmon runs and village sites. Indian resistance all along the trail persisted into the 1880s. By then the Indians had suffered military defeats, settlers had claimed their most productive lands, treaties were made and broken, and most tribes were forced onto reservations. In just a few decades the American landscape was changed forever.

An Enduring Legacy

This remarkable story began drawing to a close in 1869 with completion of the transcontinental railroad. People still used parts of the old wagon road for local trips, and the better stretches of Trail became paved roads and highways. Over the years other traces of the Oregon Trail were plowed under, built over, or faded away. In 1906, 76-year-old Ezra Meeker, who crossed the plains to Oregon in 1852, set out in a covered wagon to retrace the old Trail from west to east. He meant to mark the route before it was gone, publicize the Trail's history, and encourage protection of the wagon ruts that remained. Meeker met with two U.S. presidents, testified before Congress, and made several publicity trips along the route before his death in 1928.

In 1978 Congress authorized the old wagon road as the Oregon National Historic Trail, recognizing its importance in American hisstory. Today the Trail is administered by the National Park Service and managed by the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, other federal agencies, state and local governments, and private landowners. They work together to protect the Trail's legacy, provide public access, and tell its stories.

Timeline

Before 1700

Indians live throughout the country centuries before Europeans arrive. Although

of different tribes and languages, they establish extensive trading

networks.

1750-1800

Plains Indians obtain horses and guns. The horses provide mobility; guns enable

better hunting and defense. While explorers and fur traders follow Indian trails

west.

1800-1830

Louisiana Purchase doubles U.S. territory. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark

expedition opens American West. Monroe Doctrine initiated, keeps European powers

from meddling in U.S. affairs.

1836-1837

Missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman attend the Rendezvous in Wyoming, then

travel to Oregon territory; banks fail; economic depression sweeps United

States; eastern citizens consider a new life in the West.

Dearest mother, For two or three days past I have felt weak, restless and scarcely able to sit on my horse. But see how I have been diverted by the scenery, and carried out of myself in conversation about home and friends.... [recalling] my last impressions of home... I forget that I am weary and want rest.

—Narcissa Whitman, August 29, 1836.

1843

Nearly 1,000 emigrants complete the trip to Oregon. American settlers there

organize a provisional government for self-rule, separate from British or U.S.

control.

Out in Oregon I can get me a square mile of land.... Dad burn me, I am done wife this country, Winters it's frost and snow ... summers the overflow from Old Muddy drowns half my acres; taxes take the yield of them that's left.

—Peter Burnett, emigrant, 1843.

Our manifest destiny [is] to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.

—John L. Sullivan, editor, 1845

1845-1848

U.S. thirst for expansion and economic opportunity spurs thousands to hit the

trail; gold found in California.

The Oregon emigrants... are not indolent, dissolute, ignorant and vicious, but they are enterprising, orderly, intelligent and virtuous.

—Lansford Hastings, entrepreneur and trail promoter, 1845

This country was once covered with buffalo ... Since the white man has made a road across our land, and has killed off our game, we are hungry... Our women and children cry for food and we have no food give them.

—Chief Washakie, Eastern Shoshone, 1855

1849-1850

Colera kills thousands of overlanders; Donation Land Act of 1850 promotes

homesteading in Oregon and allows a married woman to hold land in her own

name.

1851-1861

About one-third who cross the plains are women, 1852; Oregon gains statehood,

1859; Pony Express company delivers fast, up-to-date news, unites East and West

coasts.

1862-1869

Indians rise up as white settlement leads to loss of traditional homeland and

broken treaties; transcontinental railroad completed, signals end of covered

wagon travel.

QUILTS MADE BY PIONEER WOMEN were more than bed covers. The impressionistic designs reflected their experiences—remembering back home, enduring Trail life, and beginning anew in Oregon.

On the Trail

INDEPENDENCE: This was the preferred jumping off point for the Oregon and Santa Fe trails in the 1840s and early 1850s.

FORT KEARNEY: The U.S. Army built the fort in 1848 to protect emigrants. All trails from jumping off points along the Missouri River met here at the Gateway to the Great Plains.

ASH HOLLOW: This was the entry to the North Platte River Valley. Ample supplies of wood, water, and grass made this a sought-after camping area.

SCOTTS BLUFF: When emigrants reached this prominent landmark, they knew that a third of their trip was finished.

FORT LARAMIE: Between the early 1830s and the late 1840s this outpost went from an Indian trading post to a major resupply point for emigrants and a major military post. Old Bedlam, on the fort grounds, is the oldest structure in Wyoming.

REGISTER CLIFF: Of the thousands of names carved by emigrants into the soft sandstone, hundreds are still legible. Trail ruts, some as deep as five feet, are three miles west.

INDEPENDENCE ROCK: Fur trappers named this formation on July 4, 1824. Many emigrants carved or painted their names on the rock.

SOUTH PASS: Here emigrants crossed the Continental Divide into Oregon Country. The pass is so broad and level that many did not realize they had entered the Pacific watershed.

FORT BRIDGER: The fort was a major supply point on the trail. Here the Mormon Trail veered off to the southwest and into Utah.

THREE ISLAND CROSSING: At low water this was the best crossing to the north side of the Snake River—and to better travel conditions that also offered ample drinking water.

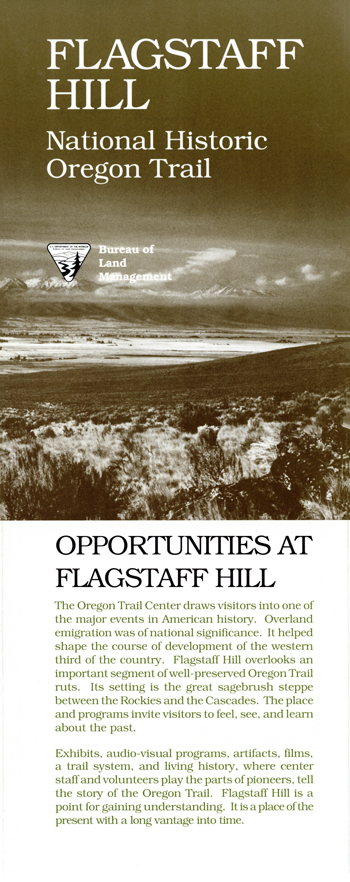

FLAGSTAFF HILL: Travelers first saw the Blue Mountains from here—an indication that their trip was nearing its end.

WHITMAN MISSION: In 1836 Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, who helped blaze the Oregon Trail route, set up a mission here to Christianize the Indians.

BLUE MOUNTAINS: The abundant wood, water, and shade afforded by these mountains were a welcome change from the desert terrain along the Snake River.

THE DALLES: Before the Barlow Road opened in 1846, emigrants had to build rafts and float down the treacherous Columbia.

BARLOW PASS: Tired and weary emigrants who chose not to go down the Columbia faced a steep climb to the pass before descending into the Willamette Valley.

OREGON CITY: The Oregon Trail ended here. Fort Vancouver, a Hudson's Bay Company trading post, is across the Columbia in Washington.

Planning Your Visit

(click for larger map) |

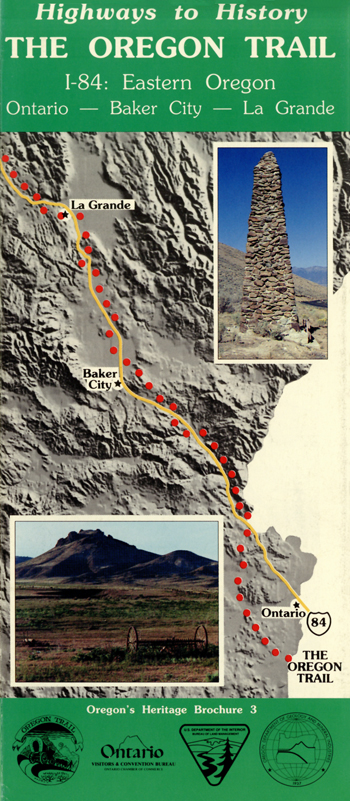

Along the Trail corridor today you can visit hundreds of historic sites, landmarks, and scenic overlooks, and see about 300 miles of wagon traces (ruts). An auto route follows the Trail between Independence, Mo., and Oregon City, Ore. For information about services in communities or Trail sites, contact area chambers of commerce and state divisions of tourism.

National Trails System Office

National Park Service

124 South State Street, Ste. 200

Salt Lake City, UT 84111

Auto Tour Route Interpretive Guides provide Trail highlights and driving directions. Contact the National Trails System Office (above) or visit: www.nps.gov/oreg.

Bureau of Land Management

www.blm.gov/or/oregontrail

U.S. Forest Service

www.fs.fed.us/recreation/programs/trails/nat_trails.shtml

Oregon-California Trail Association

www.octa-trails.org

National Frontier Trails Center

www.ci.independence.mo.us/nftm

Source: NPS Brochure (2014)

|

Establishment Oregon National Historic Trail — 1978 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Brochures ◆ Site Bulletins ◆ Trading Cards

Documents

Auto Tour Route Interpretive Guides (National Historic Trails)

Western Missouri Through Northeastern Kansas (Map) (September 2005)

Nebraska and Northeastern Colorado (Map) (August 2006)

Across Wyoming (Map) (July 2007)

Along the Snake River Plain Through Idaho (Map) (October 2008)

Across Oregon (Map) (June 2023)

Blazing a Trail to Oregon: Jumping-Off at St. Joseph (Morris Werner, extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 14 No. 3, Autumn 1991)

Comprehensive Management and Use Plan, Oregon Trail National Historic Trail (August 1981)

Comprehensive Management and Use Plan — Appendix II: Primary Route, Oregon Trail National Historic Trail (August 1981)

John Jurnegan: An autobiography of travels to Fort Laramine over the Oregon and California Trail and along the Santa Fe Trail (1851-1868) (Joy L. Poole, ed., undated)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Oregon, California, Mormon Pioneer, and Pony Express National Historic Trails (August 2010)

Massacre on the Oregon Trail in the Year 1860 (Carl Schlicke, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 1 No. 1, Spring 1987; ©Washington State Historical Society)

National historic trail awareness and experience, Santa Fe, Oregon, and California National Historic Trails (extract of entire report, undated)

On Sidesaddle to the Columbia: Pioneer Travel in Feminine Fashion (Laurie Winn Carlson, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 13 No. 1, Spring 1999; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Oregon Trail Histories Oregon BLM Cultural Resources Series No. 9 (Richard C. Haines, ed., 1993)

The Glorious Fourth: Independence Day Celebrations on the Oregon Trail (Jacqueline Williams, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 9 No. 2, Summer 1995; ©Washington State Historical Society)

The Oregon Trail (Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, 1981)

The Oregon Trail: A Potential Addition to the National Trails System (June 1975)

The Kennedy Train: Meeting the Challenge of Leading a Wagon Company on the Overland Trail (Everell Cummins, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 17 No. 2, Summer 2003; ©Washington State Historical Society)

The Overland Trail: Historic Traces in the Contemporary Landscape—A Photo Essay (Greg MacGregor, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 9 No. 2, Summer 1995; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Tourists by Necessity: Overlanders in the Cosmic Landscape of the Snake River Region (Peter G. Boag, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 7 No. 3, Fall 1993; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Through the "Magnificent Gateway": The Columbia River Gorge and Early Emigrant Travel (Welson W. Rau, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 15 No. 4, Winter 2001-02; ©Washington State Historical Society)

The National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center

Books

oreg/index.htm

Last Updated: 11-Sep-2024