| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

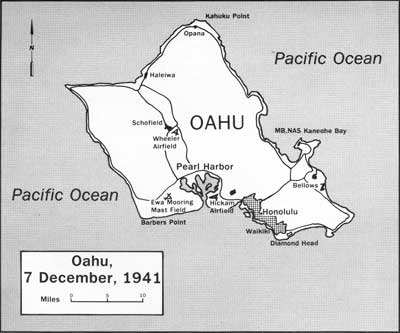

INFAMOUS DAY: Marines at Pearl Harbor by Robert J. Cressman and J. Michael Wenger Suddenly Hurled into War

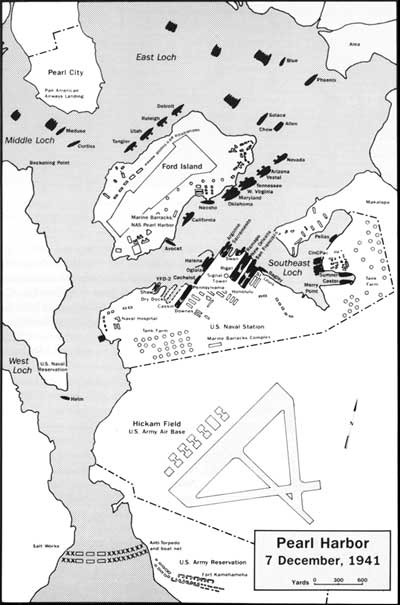

Some 200 miles north of Oahu, Vice Admiral Nagumo's First Air Fleet — formed around the aircraft carriers Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, Hiryu, Shokaku and Zuikaku pressed southward in the pre-dawn hours of 7 December 1941. At 0550, the dark gray ships swung to port, into the brisk easterly wind, and commenced launching an initial strike of 184 planes 10 minutes later. A second strike would take off after an hour's interval. Once airborne, the 51 Aichi D3A1 Type 99 dive bombers (Vals), 89 Nakajima B5N21 attack planes (Kates) used in high-level bombing or torpedo bombing roles, and 43 Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 00 fighters (Zeroes), let by Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, Akagi's air group commander, wheeled around, climbed to 3,000 meters, and droned toward the south at 0616. The only other military planes aloft that morning were Douglas SBD Dauntlesses from Enterprise, flying searches ahead of the carrier as she returned from Wake Island, Army Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses heading in from the mainland, and Navy Consolidated PBY Catalinas on routine patrols out of the naval air stations at Ford Island and Kaneohe. That morning, 15 of the ships at Pearl Harbor numbered Marine detachments among their complements; eight battleships, two heavy cruisers, four light cruisers, and one auxiliary. A 16th detachment, assigned to the auxiliary (target/gunnery training ship) Utah (AG-16), was ashore on temporary duty at the 14th Naval District Rifle Range at Luuloa Point.

At 0753, Lieutenant Frank Erickson, USCG, the Naval Air Station (NAS) Ford Island duty officer, watched Privates First Class Frank Dudovick and James D. Young, and Private Paul O. Zeller, USMCR — the Marine color guard — march up and take post for Colors. Satisfied that all looked in order outside, Erickson stepped back into the office to check if the assistant officer-of-the-day was ready to play the recording for sounding Colors on the loudspeaker. The sound of two heavy explosions, however, sent the Coast Guard pilot running to the door. He reached it just in time to see a Kate fly past 1010 Dock and release a torpedo. The markings on the plane — "Which looked like balls of fire" — left no question as to its identity; the explosion of the torpedo as it struck the battleship California (BB-44) moored near the administration building, left no doubt as to its intent. "The Marines didn't wait for colors," Erickson recalled later, "The flag went right up but the tune was general quarters." As "all Hell" broke loose around them, Dudovick, Young, and Zeller unflinchingly hoisted the Stars and Stripes "with the same smartness and precision" that had characterized their participation in peacetime ceremonies. At the crew barracks on Ford Island, Corporal Clifton Webster and Private First Class Albert E. Yale headed for the roof immediately after general quarters sounded. In the direct line of fire from strafing planes, they set up a machine gun. Across Oahu, as Japanese planes swept in over NAS Kaneohe Bay, the Marine detachment there — initially the only men who had weapons — hurried to their posts and began firing at the attackers.

Since the American aircraft carriers were at sea, the Japanese targeted the battleships which lay moored off Ford Island. At one end of Battleship Row lay Nevada. At 0802, the battleship's .50-caliber machine guns opened fire on the torpedo planes bearing down on them from the direction of the Navy Yard; her gunners believed that they had shot one down almost immediately. An instant later, however, a torpedo penetrated her port side and exploded. Ahead of Nevada lay Arizona, with the repair ship Vestal (AR-4) alongside, preparing for a tender availability. Major Alan Shapley had been relieved the previous day as detachment commanding officer by Captain John H. Earle, Jr., who had come over to Arizona from Tennessee (BB-43). Awaiting transportation to the Naval Operating Base, San Diego, and assignment to the 2d Marine Division, Shapley was lingering on board to play first base on the battleship's baseball team in a game scheduled with the squad from the carrier Enterprise (CV-6). After the morning meal, he started down to his cabin to change. Seated at breakfast, Sergeant John M. Baker heard the air raid alarm, followed closely by an explosion in the distance and machine gun fire. Corporal Earl C. Nightingale, leaving the table, had paid no heed to the alarm at the outset, since he had no antiaircraft battle station, but ran to the door on the port side that opened out onto the quarterdeck at the sound of the distant explosion. Looking out, he saw what looked like a bomb splash alongside Nevada. Marines from the ship's color guard then burst breathlessly into the messing compartment, saying that they were being attacked.

As general quarters sounded, Baker and Nightingale, among the others, headed for their battle stations. Aft, congestion at the starboard ladder, that led through casemate no. 9, prompted Second Lieutenant Carleton E. Simensen, USMCR, the ship's junior Marine officer, to force his way through. Both Baker and Nightingale noted, in passing, that the 5-inch/51 there was already manned, and Baker heard Corporal Burnis L. Bond, the gun captain, tell the crew to train it out. Nightingale noted that the men seemed "extremely calm and collected." As Lieutenant Simensen led the Marines up the ladder on the starboard side of the mainmast tripod, an 800-kilogram converted armor-piercing shell dropped by a Kate from Kaga ricocheted off the side of Turret IV. Penetrating the deck, it exploded in the vicinity of the captain's pantry. Sergeant Baker was following Simensen up the mainmast when the bomb exploded, shrapnel cutting down the officer as he reached the first platform. He crumpled to the deck. Nightingale, seeing him flat on his back, bent over him to see what he could do but Simensen, dying, motioned for his men to continue on up the ladder. Nightingale continued up to Secondary Aft and reported to Major Shapley that nothing could be done for Simensen. An instant later, a rising babble of voices in the secondary station prompted Nightingale to call for silence. No sooner had the tense quiet settled in when, suddenly, a terrible explosion shook the ship, as a second 800-kilogram bomb — dropped by a Kate from Hiryu — penetrated the deck near Turret II and set off Arizona's forward magazines. An instant after the terrible fireball mushroomed upward, Nightingale looked out and saw a mass of flames forward of the mainmast, and much in the tradition of Private William Anthony of the Maine reported that the ship was afire*. "We'd might as well go below," Major Shapley said, looking around, "we're no good here." Sergeant Baker started down the ladder. Nightingale, the last man out, followed Shapley down the port side of the mast, the railings hot to the touch as they made their way below.

Baker had just reached the searchlight platform when he heard someone shout: "You can't use the ladder." Private First Class Kenneth D. Goodman, hearing that and apparently assuming (incorrectly, as it turned out) that the ladder down was indeed unusable, instinctively leapt in desperation to the crown of Turret III. Miraculously, he made the jump with only a slight ankle injury. Shapley, Nightingale, and Baker, however, among others, stayed on the ladder and reached the boat deck, only to find it a mass of wreckage and fire, with the bodies of the slain lying thick upon it. Badly charred men staggered to the quarterdeck. Some reached it only to collapse and never rise. Among them was Corporal Bond, burned nearly black, who had been ordering his crew to train out no. 9 5-inch/51 at the outset of the battle; sadly, he would not survive his wounds. Shapley and Corporal Nightingale made their way across the ship between Turret III and Turret IV, where Shapley stopped to talk with Lieutenant Commander Samuel G. Fuqua, Arizona's first lieutenant and, by that point, the ship's senior officer on board. Fuqua, who appeared "exceptionally clam," as he helped men over the side, listened as Shapley told him that it appeared that a bomb had gone down the stack and triggered the explosion that doomed the ship. Since fighting the massive fires consuming the ship was a hopeless task, Fuqua told the Marine that he had ordered Arizona abandoned. Fuqua, the first man Sergeant Baker encountered on the quarterdeck, proved an inspiration. "His calmness gave me courage," Baker later declared, "and I looked around to see if I could help." Fuqua, however, ordered him over the side, too. Baker complied.

Shapley and Nightingale, meanwhile, reached the mooring quay alongside which Arizona lay when an explosion blew them into the water. Nightingale started swimming for a pipeline 150 feet away but soon found that his ebbing strength would not permit him to reach it. Shapley, seeing the enlisted man's distress, swam over and grasped his shirt front, and told him to hang onto his shoulders. The strain of swimming with Nightingale, however, proved too much for even the athletic Shapley, who began to experience difficulties himself. Seeing his former detachment commander foundering, Nightingale loosened his grip on his shoulders and told him to go the rest of the way alone. Shapley stopped, however, and firmly grabbed him by the shirt; he refused to let go. "I would have drowned," Nightingale later recounted, "but for the Major." Sergeant Baker had seen their travail, but, too far away to help, made it to Ford Island alone. Several bombs, meanwhile, fell close aboard Nevada, moored astern of Arizona, which had begun to hemorrhage fuel from ruptured tanks. Fire spread to the oil that lay thick upon the water, threatening Nevada. As the latter counterflooded to correct the list, her acting commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Francis, J. Thomas, USNR, decided that his ship had to get underway "to avoid further danger due to proximity of Arizona." After receiving a signal from the yard tower to stand out of the harbor, Nevada singled up her lines at 0820. She began moving from her berth 20 minutes later. Oklahoma, Nevada's sister ship moored inboard of Maryland in berth F-5, meanwhile manned air-defense stations at about 0757, to the sound of gunfire. After a junior officer passed the word over the general announcing system that it was not a drill — providing a suffix of profanity to underscore the fact — all men not having an antiaircraft defense station were ordered to lay below the armored deck. Crews at the 5-inch and 3-inch batteries, meanwhile, opened ready-use lockers. A heavy shock, followed by a loud explosion, came soon thereafter as a torpedo slammed home in the battleship's port side. The "Okie" soon began listing to port. Oil and water cascaded over the decks, making them extremely slippery and silencing the ready-duty machine gun on the forward superstructure. Two more torpedoes struck home. The massive rent in the ship's side rendered the desperate attempts at damage control futile. As Ensign Paul H. Backus hurried from his room to his battle station on the signal bridge, he passed his friend Second Lieutenant Harry H. Gaver, Jr., one of Oklahoma's Marine detachment junior officers, "on his knees, attempting to close a hatch on the port side, alongside the barbette [of Turret I] ... part of the trunk which led from the main deck to the magazines ... There were men trying to come up from below at the time Harry was trying to close the hatch ..." Backus never saw Gaver again.

As the list increased and the oily, wet decks made even standing up a chore, Oklahoma's acting commanding officer ordered her abandoned to save as many lives as possible. Directed to leave over the starboard side, away from the direction of the roll, most of Oklahoma's men managed to get off, to be picked up by boats arriving to rescue survivors. Sergeant Thomas E. Hailey, and Privates First Class Marlin "S" Seale and James H. Curran, Jr., swam to he nearby Maryland. Hailey and Seale turned to the task of rescuing shipmates, Seale remaining on Maryland's blister ledge throughout the attack, puling men from the water. Later, although inexperienced with that type of weapon, Hailey and Curran manned Maryland's antiaircraft guns. West Virginia rescued Privates George B. Bierman and Carl R. McPherson, who not only helped rescue others from the water but also helped to fight that battleships' fires.

Sergeant Woodrow A. Polk, a bomb fragment in his left hip, sprained his right ankle in abandoning ship, while someone clambered into a launch over Sergeant Leo G. Wears and nearly drowned him in the process. Gunnery Sergeant Norman L. Currier stepped from Oklahoma's red hull to a boat, dry-shod. Wears — as Hailey and Curran — soon found a short-handed antiaircraft gun on Maryland's boat deck and helped pass ammunition. Private First Class Arthur J. Bruktenis, whose column in the December 1941 issue of The Leatherneck would be the last to chronicle the peacetime activities of Oklahoma's Marines, dislocated his left shoulder in the abandonment, but survived.

A little over two weeks shy of his 23d birthday, Corporal Willard D. Darling, an Oklahoma Marine who was a native Oklahoman, had meanwhile clambered on board a motor launch. As it headed shoreward, Darling saw 51-year-old Commander Fred M. Rohow (Medical Corps), the capsized battleship's senior medical officer, in a state of shock, struggling in the oily water. Since Rohow seemed to be drowning, Darling unhesitatingly dove in and, along with Shipfitter First Class William S. Thomas, kept him afloat until a second launch picked them up. Strafing Japanese planes and shrapnel from American guns falling around them prompted the abandonment of the launch at a dredge pipeline, so Darling jumped in and directed the doctor to follow him. Again, the Marine rescued Rohow — who proved too exhausted to make it on his own — and towed him to shore. Maryland, meanwhile inboard of Oklahoma, promptly manned her antiaircraft guns at the outset of the attack, her machine guns opening fire immediately. She took two bomb hits, but suffered only minor damage. Her Marine detachment suffered no casualties. On board Tennessee (BB-43), Marine Captain Chevey S. White, who had just turned 28 the day before, was standing officer-of-the-deck watch as that battleship lay moored inboard of West Virginia (BB-48) in berth F-6. Since the commanding officer and the executive officer were both ashore, command devolved upon Lieutenant Commander James W. Adams, Jr., the ship's gunnery officer. Summoned topside at the sound of the general alarm and hearing "all hand to general quarters" over the ship's general announcing system, Adams sprinted to the bridge and spotted White en route. Over the din of battle, Adams shouted for the Marine to "get the ship in condition Zed [i.e.: establish water-tight integrity] as quickly as possible." Whit did so. By the time Adams reached his battle station on the bridge, White was already at his own battle station, directing the ship's antiaircraft guns. During the action (in which the ship took one bomb that exploded on the center gun of Turret II and another that penetrated the crown of Turret III, the latter breaking apart without exploding), White remained at his unprotected station, coolly and courageously directing the battleship's antiaircraft battery. Tennessee claimed four enemy planes shot down.

West Virginia , outboard of Tennessee, had been scheduled to sail for Puget Sound, due for overhaul, on 17 November, but had been retained in Hawaiian waters owing to the tense international situation. In her exposed moorings, she thus absorbed six torpedoes, while a seventh blew her rudder free. Prompt counter-flooding, however, prevented her from turning turtle as Oklahoma had done, and she sank, upright, alongside Tennessee. On board California, moored singly off the administration building at the naval air station, junior officer of the deck on board had been Second Lieutenant Clifford B. Drake. Relieved by Ensign Herbert C. Jones, USNR, Drake went down to the wardroom for breakfast (Kadota figs, followed by steak and eggs) where, around 0755, he heard airplane engines and explosions as Japanese dive bombers attacked the air station. The general quarters alarm then summoned the crew to battle stations. Drake, forsaking his meal, hurried to the foretop. By 0803, the two ready machine guns forward of the bridge had opened fire, followed shortly thereafter by guns no. 2 and 4 of the antiaircraft battery. As the gunners depleted the ready-use ammunition, however, two torpedoes struck home in quick succession. California began to settle as massive flooding occurred. Meanwhile, fumes from the ruptured fuel tanks — she had been fueled to 95 percent capacity the previous day — drove out the men assigned to the party attempting to bring up ammunition for the guns by hand. A call for men to bring up additional gas masks proved fruitless, as the volunteers, who included Private Arthur E. Senior, could not reach the compartment in which they were stored. California's losing power because of the torpedo damage soon relegated Lieutenant Drake, in her foretop, to the role of "... a reporter of what was going on ... a somewhat confused young lieutenant suddenly hurled into war." As California began listing after the torpedo hits, Drake began pondering his own ship's fate. Comparing his ship's list with that of Oklahoma's, he dismissed California's rolling over, thinking, "who ever heard of a battleship capsizing?" Oklahoma, however, did a few moments later.

Meanwhile, at about 0810, in response to a call for a chain of volunteers to pass 5-inch/25 ammunition, Private Senior again stepped forward and soon clambered down to the C-L Division Compartment. There he saw Ensign Jones, Lieutenant Drake's relief earlier that morning, standing at the foot of the ladder on the third deck, directing the ammunition supply. For almost 20 minutes, Senior and his shipmates toiled under Jones' direction until a bomb penetrated the main deck at about 0830, and exploded on the second deck, plunging the compartment into darkness. As acrid smoke filled the compartment, Senior reached for his gas mask, which he had lain on a shell box behind him, and put it on. Hearing someone say: "Mr. Jones has been hit," Senior flashed his flashlight over on the ensign's face and saw that "it was all bloody. His white coat also had blood all over it." Senior and another man then carried Jones as far as the M Division compartment, but the ensign would not let them carry him any further. "Leave me alone," he gasped insistently, "I'm done for. Get out of here before the magazines go off!" Soon thereafter, however, before he could get clear, Senior felt the shock of an explosion from down below and collapsed, unconscious. Jones' gallantry — which earned him a posthumous Medal of Honor — impressed Private Howard M. Haynes, who had been confined before the attack, awaiting a bad conduct discharge. After the battle, a contrite Haynes — "a mean character who had shown little or no respect for anything or anyone" before 7 December — approached Lieutenant Drake and said that he [Haynes] was alive because of the actions that Ensign Jones had taken. "God," he said, "give me a chance to prove I'm worth it." His actions that morning in the crucible of war earned Haynes a recommendation for retention in the service. Most of California's Marines, like Haynes, survived the battle. Private First Class Earl. D. Wallen and Privates Roy E. Lee, Jr. and Shelby C. Shook, however, did not. Nor did the badly burned Private First Class John A. Blount, Jr., who succumbed to his wounds on 9 December.

Nevada's attempt to clear the harbor, meanwhile, inspired those who witnessed it. Her magnificent effort prompted a stepped-up effort by Japanese dive bomber pilots to sink here. One 250-kilogram bomb hit her boat deck just aft of a ventilator trunk and 12 feet to the starboard side of the centerline, about halfway between the stack and the end of the boat deck, setting off laid-out 5-inch ready-use ammunition. Spraying fragments decimated the gun crews. The explosion wrecked the galley and blew open the starboard door of the compartment, venting into casemate no. 9 and starting a fire that swept through the casemate, wrecking the gun. Although he had been seriously wounded by the blast that had hurt both of his legs and stripped much of his uniform from his body, Corporal Joe R. Driskell disregarded his own condition and insisted that he man another gun. He refused medical treatment, assisting other wounded men instead, and then helped battle the flames. He did not quit until those fires were out. Another 250-kilogram bomb hit Nevada's bridge, penetrating down into casemate no. 6 and starting a fire. The blast had also severed the water pipes providing circulating water to the water-cooled machine guns on the foremast — guns in the charge of Gunnery Sergeant Charles E. Douglas. Intense flames enveloped the forward superstructure, endangering Douglas and his men, and prompting orders for them to abandon their station. They steadfastly remained at their posts, however, keeping the .50-caliber Brownings firing amidst the swirling black smoke until the end of the action. Unlike the battleships the enemy had caught moored on Battleship Row, Pennsylvania (BB-38), the fleet flagship, lay on keel blocks, sharing Dry Dock No. 1 at the Navy Yard with Cassin (DD-372) and Downes (DD-375) — two destroyers side-by-side ahead of her. Three of Pennsylvania's four propeller shafts had been removed and she was receiving all steam, power, and water from the yard. Although her being in drydock had excused her from taking part in antiaircraft drills, her crew swiftly manned her machine guns after the first bombs exploded among the PBY flying boats parked on the south end of Ford Island. "Air defense stations" then sounded, followed by "general quarters." Men knocked the locks off ready-use ammunition stowage and Pennsylvania opened fire about 0802.

The fleet flagship and the two destroyers nestled in the drydock ahead of her led a charmed life until dive bombers from Soryu and Hiryu targeted the drydock area between 0830 and 0915.* One bomb penetrated Pennsylvania's boat deck, just to the rear of 5-inch/25 gun no. 7, and detonated in casemate no. 9. Of Pennsylvania's Marine detachment, two men (Privates Patrick P. Tobin and George H. Wade, Jr.) died outright, 13 fell wounded, and six were listed as missing. Three of the wounded — Corporal Morris E. Nations and Jesse C. Vincent, Jr., and Private First Class Floyd D. Stewart — died later the same day.

As the onslaught descended upon the battleships and the air station, Marine detachments hurried to their battle stations on board other ships elsewhere at Pearl. In the Navy Yard lay Argonne (AG-31), the flagship of the Base Force, the heavy cruisers New Orleans (CA-32) and San Francisco (CA-38), and the light cruisers Honolulu (CL-48), St. Louis (CL-49) and Helena (CL-50). To the northeast of For Island lay the light cruiser Phoenix (CL-43). Although Utah was torpedoed and sunk at her berth early in the attack, her 14 Marines, on temporary duty at the 14th Naval District Rifle Range, found useful employment combating the enemy. The Fleet Machine Gun School lay on Oahu's south coast, west of the Pearl Harbor entrance channel, at Fort Weaver. The men stationed there, including several Marines on temporary duty from the carrier Enterprise and the battleships California and Pennsylvania, sprang to action at the first sounds of war. Working with the men from the Rifle Range, all hands set up and mounted guns, and broke out and belted ammunition between 0755 and 0810. All those present at the range were issued pistols or rifles from the facility's armory. Soon after the raid began, Platoon Sergeant Harold G. Edwards set about securing the camp against any incursion the Japanese might attempt from the landward side, and also supervised the emplacement of machine guns along the beach. lieutenant (j.g.) Roy R. Nelson, the officer in charge of the Rifle Range, remembered the many occasions when Captain Frank M. Reinecke, commanding officer of Utah's Marine detachment and the senior instructor at the Fleet Machine Gun School (and, as his Naval Academy classmates remembered, quite a conversationalist), had maintained that the school's weapons would be a great asset if anybody ever attacked Hawaii. By 0810, Reinecke's gunners stood ready to prove the point and soon engaged the enemy — most likely torpedo planes clearing Pearl Harbor or high-level bombers approaching from the south. Nearby Army units, perhaps alerted by the Marines' fire, opened up soon thereafter. Unfortunately, the eager gunners succeeded in downing one of two SBDs from Enterprise that were attempting to reach Hickam Field. An Army crash boat, fortunately, rescued the pilot and his wounded passenger soon thereafter. On board Argonne, meanwhile, alongside 1010 Dock, her Marines manned her starboard 3-inch/23 battery and her machine guns. Commander Fred W. Connor, the ship's commanding officer, later credited Corporal Alfred Schlag with shooting down one Japanese plane as it headed for Battleship Row. When the attack began, Helena lay moored alongside 1010 Dock,

the venerable minelayer Oglala (CM-3) outboard. A signalman,

standing watch on the light cruiser's signal bridge at 0757 identified

the planes over Ford Island as Japanese, and the ship went to general

quarters. Before she could fire a shot in her own defense, however, one

800-kilogram torpedo barreled into her starboard side about a minute

after the general alarm had begun summoning her men to their battle

stations. The explosion vented up from the forward engine room through

the hatch and passageways, catching many of the crew running to their

stations, and started fires on the third deck. Platoon Sergeant Robert

W. Teague, Privates First Class Paul F. Huebner, Jr.

To the southeast, New Orleans lay across the pier from her sister ship San Francisco. The former went to general quarters soon after enemy planes had been sighted dive-bombing Ford Island around 0757. At 08805, as several low-flying torpedo planes roared by, bound for Battleship Row, Marine sentries on the fantail opened fire with rifles and .45s. New Orleans' men, meanwhile, so swiftly manned the 1.1-inch/75 quads, and .50-caliber machine guns, under the direction of Captain William R. Collins, the commanding officer of the ship's Marine detachment, that the ship actually managed to shoot at torpedo planes passing her stern. San Francisco, however, under major overhaul with neither operative armament nor major caliber ammunition on board, was thus restricted to having her men fire small arms at whatever Japanese planes came within range. Some of her crew, though, hurried over to New Orleans, which was near-missed by one bomb, and helped man her 5-inchers. St. Louis, outboard of Honolulu, went to general quarters at 0757 and opened fire with her 1.1 quadruple mounted antiaircraft and .50-caliber machine gun batteries, and after getting her 5-inch mounts in commission by 0830 — although without power in train — she hauled in her lines at 0847 and got underway at 0831. With all 5-inchers in full commission by 0947, she proceeded to sea, passing the channel entrance buoys abeam around 1000. Honolulu, damaged by a near miss from a bomb, remained moored at her berth throughout the action. Phoenix, moored by herself in berth C-6 in Pearl Harbor, to the northeast of Ford Island, noted the attacking planes at 0755 and went to general quarters. Her machine gun battery opened fire at 0810 on the attacking planes as they came within range; her antiaircraft battery five minutes later. Ultimately, after two false starts (where she had gotten underway and left her berth only to see sortie signals cancelled each time) Phoenix cleared the harbor later that day and put to sea. For at least one Marine, though, the day's adventure was not over when the Japanese planes departed. Search flights took off from Ford Island, pilots taking up utility aircraft with scratch crews, to look for the enemy carriers which had launched the raid. Mustered at the naval air station on Ford Island, Oklahoma's Sergeant Hailey, still clad in his oil-soaked underwear, volunteered to go up in a plane that was leaving on a search mission at around 1130. He remained aloft in the plane, armed with a rifle, for some five hours. After the attacking planes had retired, the grim business of cleaning up and getting on with the war had to be undertaken. Muster had to be taken to determine who was missing, who was wounded, who lay dead. Men sought out their friends and shipmates. First Lieutenant Cornelius C. Smith, Jr., from the Marine Barracks at the Navy Yard, searched in vain among the maimed and dying at the Naval Hospital later that day, for his friend Harry Gaver from Oklahoma. Death respected no rank. The most senior Marine to die that day was Lieutenant Colonel Daniel R. Fox, the decorated World War I hero and the division Marine officer on the staff of the Commander, Battleship Division One, Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd, who, along with Lieutenant Colonel Fox, had been killed in Arizona. The tragedy of Pearl Harbor struck some families with more force than others: numbered among Arizona's lost were Private Gordon E. Shive, of the battleship's Marine detachment, and his brother, Radioman Third Class Malcolm H. Shive, a member of the ship's company. Over the next few days, Marines from the sunken ships received reassignment to other vessels — Nevada's Marines deployed ashore to set up defensive positions in the fields adjacent to the grounded and listing battleship — and the dead, those who could be found, were interred with appropriate ceremony. Eventually, the deeds of Marines in the battleship detachments were recognized by appropriate commendations and advancements in ratings. Chief among them, Gunnery Sergeant Douglas, Sergeant Hailey, and Corporals Driskell and Darling were each awarded the Navy Cross. For his "meritorious conduct at the peril of his own life," Major Shapley was commended and awarded the Silver Star. Lieutenant Simensen was awarded a posthumous Bronze Star, while Tennessee's commanding officer commended Captain White for the way in which he had directed that battleship's antiaircraft guns that morning. Titanic salvage efforts raised some of the sunken battleships — California, West Virginia, and Nevada — and they, like the surviving Marines, went on to play a part in the ultimate defeat of the enemy who had begun the war with such swift and terrible suddenness.

|