| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

INFAMOUS DAY: Marines at Pearl Harbor by Robert J. Cressman and J. Michael Wenger They Caught Us Flat-Footed At 0740, when Fuchida's fliers had closed to within a few miles of Kahuku Point, the 43 Zeroes split away from the rest of the formation, swinging out north and west of Wheeler Field, the headquarters of the Hawaiian Air Force's 18th Pursuit Wing. Passing further to the south, at about 0745 the Soryu and Hiryu divisions executed a hard diving turn to port and headed north, toward Wheeler. Eleven Zeroes from Shokaku and Zuikaku simultaneously left the formation and flew east, crossing over Oahu north of Pearl Harbor to attack NAS Kaneohe Bay. Eighteen from Akagi and Kaga headed toward what the Japanese called Babasu Pointo Hikojo (Barbers Point Airdrome) — Ewa Mooring Mast Field. Sweeping over the Waianae Range, Lieutenant Commander Shigeru Itaya led Akagi's nine Zeroes, while Lieutenant Yoshio Shiga headed another division of nine from Kaga. After the initial attack, Itaya and Shiga were to be followed by divisions from Soryu, under Masaji Suganami, and Hiryu, under Lieutenant Kiyokuma Okajima, which were, at that moment, involved in attacking Wheeler to the north.

In the officers' mess at Ewa, the officer-of-the-day, Captain Leonard W. Ashwell of VMJ-252, noticed two formations of aircraft at 0755. The first looked like 18 "torpedo planes" flying at 1,000 feet toward Pearl Harbor from Barbers Point, but the second, to the northwest, comprised about 21 planes just coming over the hills, from the direction of Nanakuli, also at an altitude of about 1,000 feet. Ashwell, intrigued by the sight, stepped outside for a better look. The second formation, of single-seat fighters (the two division from Akagi and Kaga), flew just to the north of Ewa and wheeled to the right. Then, flying in a "string" formation, they commenced firing. Recognizing the planes as Japanese, Ashwell burst back into the mess, shouting: "Air Raid ... Air Raid! Pass the word!" He then sprinted for the guard house, to have "call to arms" sounded.

That Sunday morning, Technical Sergeant Henry H. Anglin, the noncommissioned-officer-in-charge of the photographic section at Ewa, had driven from his Pearl City home with his three-year-old son, Hank, to take the boy's picture at the station. The senior Anglin had just positioned the lad in front of the camera and was about to take the photo — the picture was to be a gift to the boy's grandparents — when they heard the "mingled noise of airplanes and machine guns." Roaring down to within 25 feet of the ground, Itaya's group most likely carried out only one pass at their targets before moving on to Hickam, the headquarters of the Hawaiian Air Force's 18th Bombardment Wing.

Thinking that Army pilots were showing off, Sergeant Anglin stepped outside the photographic section tent and, along with some other enlisted men, watched planes bearing Japanese markings strafing the edge of the field. Then, the planes began roaring down toward the field itself and the bullets from their cowl and wing-mounted guns began kicking up puffs of dirt. "Look, live ammunition," somebody said or thought, "Somebody'll go to prison for this." Shiga's pilots, like Itaya's, concentrated on the tactical aircraft lined up neatly on Ewa's northwest apron with short bursts of 7.7- and 20-millimeter machine gun fire. Shiga's pilots, unlike Itaya's, however, reversed course over the treetops and repeated their blistering attacks from the opposite direction. Within minutes, most of MAG-21's planes sat ablaze and exploding, black smoke corkscrewing into the sky. The enemy spared none of the planes: the gray BD-1s and -2s of VMSB-232 and the seven spare SB2U-3s left behind by VMSB-231 when they embarked in Lexington just two days before. VMF-211's remaining F4F-3s, left behind when the squadron deployed to Wake well over a week before, likewise began exploding in flame and smoke. At his home on Ewa Beach, three miles southeast of the air station, Captain Richard C. Mangrum, VMSB-232's flight officer, sat reading the Sunday comics. Often residents of that area had heard gunnery exercises but on a Sunday morning? The chatter of gunfire and the dull thump of explosions, however, drew Mangrum's attention away from the cartoons. As he looked out his front door, planes with red ball markings on the wings and fuselage roared by at very low altitude, bound for Pearl Harbor. up the valley in the direction of Wheeler Field, smoke was boiling skyward, as it was from Ewa. As he set out for Ewa on an old country road, wives and children of Marines who lived in the Ewa Beach neighborhood began gathering at the Mangrums' house.

Elsewhere in the Ewa Beach community, Mrs. Charles S. Barker, Jr., wife of Master Technical Sergeant Barker, the chief clerk in MAG-21's operations office, hear the noise and asked: "What's all the shooting?" Barker, clad only in beach shorts, looked out his front door, saw and heard a plane fly by at low altitude, and then saw splashes along the shoreline from strafing planes marked with red hinomaru. Running out to turn off the water hose in his front yard, and seeing a small explosion nearby (probably an antiaircraft shell from the direction of Pearl), Barker had seen enough. He left his wife and baby with his neighbors, and set out for Ewa.

The strafers who singled out cars moving along the roads that led to Ewa proved no respecter of persons. MAG-21's commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Claude A. "Sheriff" Larkin, en route from Honolulu, was about a mile from Ewa in his 1930 Plymouth when a Zero shot at him. He momentarily abandoned the car for the relative sanctuary of a nearby ditch, not even bothering to turn off the engine, and then, as the strafer roared out of sight, sprinted back to the vehicle, jumped back in, and sped on. He reached his destination at 0805 — just in time to be machine gunned again by one of Admiral Nagumo's fighters. Soon thereafter, Larkin's good fortune at remaining unwounded amidst the attack ran out, as he suffered several penetrating wounds, the most painful of which included one on the top of the middle finger of his left hand and another on the front of his lower left leg just above the top of his shoe. Refusing immediate medical attention, though, Larkin continued to direct the defense of Ewa Field. Pilots and ground crewmen alike rushed out onto the mat to try to save their planes from certain destruction. At least a few pilots intended to get airborne, but could not because most of their aircraft were either afire or riddled beyond any hope of immediate use. Captain Milo G. Haines of VMF-211 sought safety behind a tractor, he and the machine's driver taking shelter on the side opposite to the strafers. Another Zero came in from another angle, however, and strafed them from that direction. Spraying bullets clipped off Haines' necktie just beneath his chin. Then, as a momentarily relieved Haines put his right hand at the back of his head a bullet lacerated his right little finger and a part of his scalp.

In the midst of the confusion, an excited three-year old Hank Anglin innocently took advantage of his father's distraction with the battle and wandered toward the mat. All of the noise seemed like a lot of fun. Sergeant Anglin ran after his son, got him to the ground, and, shielding him with his own body, crawled some 35 yards, little puffs of dirt coming near them at times. As they clambered inside the radio trailer to get out of harm's way, a bullet made a hole above the door. Moving back to the photo tent, the elder Anglin put his son under a wooden bench. As he set about gathering his camera gear to take pictures of the action, a bullet went through his left arm. Deprived of the use of that arm for a time, Anglin returned to the bench under which his son still crouched obediently, to see little Hank point to a spent bullet on the floor and hear him warn: "Don't touch that, daddy, it's hot."

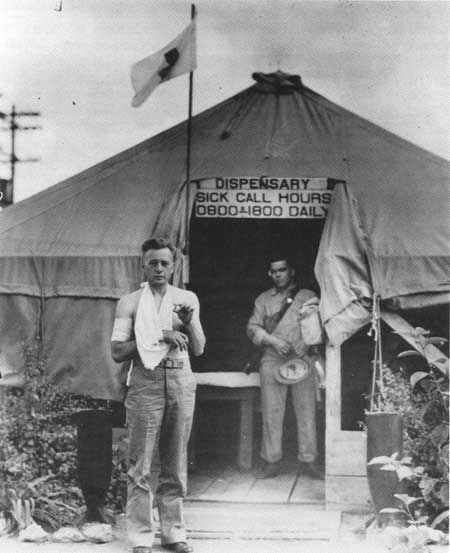

Private First Class James W. Mann, the driver assigned to Ewa's 1938 Ford ambulance, had been refueling the vehicle when the attack began. When Lieutenant Thomas L. Allman, Medical Corps, USN, the group medical officer, saw the first planes break into flames, he ordered Mann to take the ambulance to the flight line. Accompanied by Pharmacist's Mate 2d Class Orin D. Smith, a corpsman from sick bay, they sped off. The Japanese planes seemed to be attracted to the bright red crosses on the ambulance, however, and halted its progress near the mooring mast. Realizing that they were under attack, Mann floored the brake pedal and the Ford screeched to a halt. Rather than leave the vehicle for a safer area, Mann and Smith crawled underneath it so that they could continue their mission as quickly as possible. The strafing, however, continued unabated. Ironically, the first casualty Mann had to collect was the man lying prone beside him. Orin Smith felt a searing pain as one of the Japanese 7.7-millimeter rounds found its mark in the fleshy part of his left calf. Seeing that the corpsman had been hurt, Mann assisted him out from under the vehicle and up into the cab. Despite continued strafing that shot out four tires, Mann pressed doggedly ahead and delivered the wounded Smith to sick bay.

After seeing that the corpsman's bleeding was stopped and the painful wound was cleaned and dressed, Private First Class Mann sprinted to his own tent. Grabbing his rifle, he then returned to the battered ambulance and, shot-out tires flopping, drove toward Ewa's garage. There, Master Technical Sergeant Lawrence R. Darner directed his men to replace the damaged tires with those from a mobile water purifier. Meanwhile, Smith resumed his duties as a member of the dressing station crew. Also watching the smoke beginning to billow skyward was Sergeant Duane W. Shaw, USMCR, the driver of the station fire truck. Normally, during off-duty hours, the truck sat parked a quarter-mile from the landing area. Shaw, figuring that it was his job to put out the fires, climbed into the fire engine and set off. Unfortunately, like Private First Class Mann's ambulance, Sergeant Shaw's bright red engine moving across the embattled camp soon attracted strafing Zeroes. Unfazed by the enemy fire that perforated his vehicle in several places, he drove doggedly toward the flight line until another Zero shot out his tires. Only then pausing to make a hasty estimate of the situation, he reasoned that with the fire truck at least temporarily out of service he would have to do something else. Jumping down from the cab, he soon got himself a rifle and some ammunition. Then, he set out for the flight line. If he could not put out fires, he could at least do some firing of his own at the men who caused them. With the parking area cloaked in black smoke, Japanese fighter pilots shifted their efforts to the planes either out for repairs in the rear areas or to the utility planes parked north of the intersection of the main runways. Inside ten minutes' time, machine gun fire likewise transformed many of those planes into flaming wreckage. Firing only small arms and rifles in the opening stages, the Marines fought back against Kaga's fighters as best they could, with almost reckless heroism. Lieutenant Shiga remembered one particular Leatherneck who, oblivious to the machine gun fire striking the ground around him and kicking up dirt, stood transfixed, emptying his sidearm at Shiga's Zero as it roared past. years later, Shiga would describe that lone, defiant, and unknown Marine as the bravest American he had ever met. A tragic drama, however, soon unfolded amidst the Japanese attack. One Marine, Sergeant William E. Lutschan, Jr., USMCR, a truck driver, had been "under suspicion" of espionage and he was ordered placed under arrest. In the exchange of gunfire that followed his resisting being taken into custody, though, he was shot dead. With that one exception, the Marines at Ewa Field had fought back to a man.

As if Akagi's and Kaga's fighters had not sown enough destruction on Ewa, one division of Zeroes from Soryu and one from Hiryu arrived on the scene, fresh from laying waste to many of the planes at Wheeler Field. This second group of fighter pilots went about their work with the same deadly precision exhibited at Wheeler only minutes before. The raid caught master Technical Sergeant Darner's crew in the middle of changing the tires on the station's ambulance. Private First Class Mann, who by that point had managed to obtain some ammunition for his rifle, dropped down with the rest of the Marines at the garage and fired at the attacking fighters as they streaked by. Lieutenant Kiyokuma Okajima led his six fighters down through the rolling smoke, executing strafing attacks until ground fire holed the forward fuel tank of his wingman, Petty Officer 1st Class Kazuo Muranaka. When Okajima discovered the damage to Muranaka's plane, he decided that his men had pressed their luck far enough, and began to assemble his unit and shepherd them toward the rendezvous area some 10 miles west of Kaena Point. The retiring Japanese in all likelihood then spotted incoming planes from Enterprise (CV-6), that had been launched at 0618 to scout 150 miles ahead of the ship in nine two-plane sections. Their planned flight path to Pearl was to take many of them over Ewa Mooring Mast Field, where some would encounter Japanese aircraft. Meanwhile, back at Ewa, after what must have seemed an eternity, the Zeroes of the first wave at last wheeled away toward their rendezvous point. Having made a shambles of the Marine air base, Japanese pilots claimed the destruction of 60 aircraft on the ground: Akagi's airmen accounted for 11, Kaga's 15, Soryu's 12, and Hiryu's 22. Their figures were not too far off the mark, for 47 aircraft of all types had been parked at the field at the beginning of the onslaught, 33 of which had been fully operational. Although the Japanese had wreaked havoc upon MAG-21's complement of planes, the group's casualties seemed miraculously light. Apparently, the enemy fighter pilots in the first wave maintained a fairly high degree of discipline, eschewing attacks on people and concentrating their attacks on machines. Many of Ewa's Marines, however, had parked their cars near the center of the station. By the time the Japanese departed, the parking lot resembled a junk yard of mangled automobiles of various makes and models. Overcoming the initial shock of the first strafing attack, Ewa's Marines took stock of their situation. As soon as the last of Itaya's and Shiga's Zeroes had departed, Marines went out and manned stations with rifles and .30-caliber machine guns taken from damaged aircraft and from the squadron ordnance rooms. Technical Sergeant William G. Turnage, an armorer, supervised the setting up of the free machine guns. Technical Sergeant Anglin, meanwhile, took his little boy to the guard house, where a woman motorist agreed to drive Hank home to his mother. As it would turn out, that reunion was not to be accomplished until much later that day, "inasmuch as the distraught mother had already left home to look for her son." Master Technical Sergeant Emil S. Peters, a veteran of action in Nicaragua, had, during the first attack, reported to the central ordnance tent to lend a hand in manning a gun. By the time he arrived there, however, there were none left to man. Then he saw a Douglas SBD-2, one of two spares assigned to VMSB-232, parked behind the squadron's tents. Enlisting the aid of Private William G. Turner, VMSB-231's squadron clerk, Peters ran over to the ex-Lexington machine that still bore her USN markings, 2-B-6, pulled the after canopy forward, and clambered in the after cockpit, stepping hard on the foot pedal to unship the free .30-caliber Browning from its housing in the after fuselage, and then locking it in place. Turner, having obtained a supply of belted ammunition, took his place on the wing as Peter's assistant. Elsewhere, nursing his painfully wounded finger and leg, Lieutenant Colonel Larkin ordered extra guards posted on the perimeter of the filed and on the various roads leading into the base. Men not engaged in active defense went to work fighting the many fires. Drivers parked what trucks and automobiles had remained intact on the runways to prevent any possible landings by airborne troops. Although hardly transforming Ewa into a fortress, the Marines ensured that they would be ready for any future attack.

Undoubtedly, most of the men at Ewa expected — correctly — that the Japanese would return. At about 0835, enemy planes again made their appearance in the sky over Ewa, but this time, Marines stood or crouched ready and waiting for what proved to be Lieutenant Commander Takahashi's dive bombing unit from Shokaku, returning from its attacks on the naval air station at Pearl Harbor and the Army's Hickam Field, roaring in from just above the treetops. Initially, their targets appeared to be the planes, but, seeing that most had already been destroyed, the enemy pilots turned to strafing buildings and people in a "heavy and prolonged" assault.

Better prepared than they had been when Lieutenant Commander Itaya's Zeroes had opened the battle, Ewa's Marines met Takahashi's Vals with heavy fire from rifles, Thompson submachine guns, .30-caliber machine guns, and even pistols. In retaliation, after completing their strafing runs, the Japanese pilots pulled up in steep wing-overs, allowing their rear seat gunners to take advantage of the favorable deflection angle to spray the defenders with 7.7-millimeter bullets. Marine observers later recounted that Shokaku's planes also dropped light bombs, perhaps of the 60-kilogram variety, as they counted five small craters on the filed after the attack. In response to the second onslaught, as they had in the first, all available Marines threw themselves into the desperate defense of their base. The additional strafing attacks started numerous fires within the camp area, adding new columns of dense smoke to those still rising from the planes on the parking apron. Unfortunately, the ground fire seemed far more brave than accurate, because all of Shokaku's dive bombers repeatedly zoomed skyward, seemingly unhurt. Even taking into account possible damage sustained during attacks over Ford Island and Hickam, only four of Takahashi's planes sustained any damage over Oahu before they retired. The departure of Shokaku's Vals afforded Lieutenant Colonel Larkin the opportunity to reorganize the camp defenses. There was ammunition to be distributed, wounded men to be succored, and seemingly innumerable fires burning amongst the tents, buildings, and planes, to be extinguished.

However, around 0930, yet another flight of enemy planes appeared — about 15 Vals from Kaga and Hiryu. Although the pilots of those planes had expended their 250-kilogram bombs on ships at Pearl Harbor, they still apparently retained plenty of 7.7-millimeter ammunition, and seemed determined to expend much of what remained upon Ewa. As in the previous attacks by Shokaku's Vals, the last group came in at very low altitude from just over the tops of the trees surrounding the station. Quite taken by the high maneuverability of the nimble dive bombers, which they were seeing at close hand for the second time that day, the Marines mistook them for fighter aircraft with fixed landing gear. Around that time, Lieutenant Colonel Larkin saw an American plane and a Japanese one collide in mid-air a short distance away from the field. In all probability, Larkin saw Enterprise's Ensign John H.L. Vogt's Dauntless collide with a Val. Vogt had become separated from his section leader during the Pearl-bound flight in from the carrier, may have circled offshore, and then arrived over Ewa in time to encounter dive bombers from Kaga or Hiryu. Vogt and his passenger, Radioman Third Class Sidney Pierce, bailed out of the SBD, but at too low an altitude, for both died in the trees when their 'chutes failed to deploy fully. Neither of the Japanese crewmen escaped from their Val when it crashed. Fortunately for the Marines, however, the last raid proved comparatively "light and ineffectual," something Lieutenant Colonel Larkin attributed to the heavy gunfire thrown skyward. The short respite between the second and third strafing attacks had allowed Ewa's defenders t bring all possible weapons to bear against the Japanese. Technical Sergeant Turnage, after having gotten the base's machine guns set up and ready for action, took over one of the mounts himself and fired several bursts into the belly of one Val that began trailing smoke and began to falter soon thereafter. Turnage, however, was by no means the only Marine using his weapon to good effect. Master Technical Sergeant Peters and Private Turner, from their improvised position in the lamed SBD, had let fly at whatever Vals came within range of their gun. The two Marines shot down what witnesses thought were at least two of the attacking planes and discouraged strafing in that area of the station. However, the Japanese soon tired of the tenacious bravery of the grizzled veteran and the young clerk, neither of whom flinched in the face of repeated strafing. Two particular enemy pilots repeatedly peppered the grounded Dauntless with 7.7-millimeter fire, ultimately scoring hits near the cockpit area and wounding both men. Turner toppled from the wing, mortally wounded.

Another Marine who distinguished himself during the third strafing attack was Sergeant Carlo A. Micheletto of Marine Utility Squadron (VMJ) 252. During the first Japanese attack that morning, Micheletto proceeded at once to VMJ-252's parking area and went to work, helping in the attempts to extinguish the fires that had broken out amongst the squadron's parked utility planes. He continued in those labors until the last strafing attack began. Putting aside his fire-fighting equipment and grabbing a rifle, he took cover behind a small pile of lumber, and heedless of the heavy machine-gunning, continued to fire at the attacking planes until a burst of enemy fire struck him in the head and killed him instantly. Eventually, in an almost predictable way, the Japanese planes formed up and flew off to the west, leaving the once neatly manicured Mooring Mast Field smouldering. The Marines had barely had time to catch their collective breath when, at 1000, almost as a capstone to the complete chaos wreaked by the initial Japanese attack, seven more planes arrived. Their markings, however, were of a more familiar variety — red-centered blue and white stars. The newcomers proved to be a group of Dauntlesses from Enterprise, For the better part of an hour, Lieutenant Wilmer E. Gallaher, executive officer of Scouting Squadron 6, had circled fitfully over the Pacific swells south of Oahu, waiting for the situation there to settle down. At about 0945, when he had seen that the skies seemed relatively clear of Japanese planes, Gallaher decided rather than face friendly fire over Pearl he would go to Ewa instead. They had barely stopped on the strip, however, when a Marine ran out to Gallaher's plane and yelled, "For God's sake, get into the air or they'll strafe you, too!" Other Enterprise pilots likewise saw ground crews frantically motioning for them to take off immediately. Instructed to "take off and stay in the air until [the] air raid was over," the Enterprise pilots took off and headed for Pearl Harbor. Although all seven SBDs left Ewa, only three (Gallaher's, his wingman, Ensign William P. West's, and Ensign Cleo J. Dobson's) would make it as far as Ford Island. A tremendous volume of antiaircraft fire over the harbor rose to meet what was thought to be yet another attack; seeing the reception accorded Gallaher, West, and Dobson, the other four pilots — Lieutenant (jg) Hart D. Hilton and Ensigns Carlton T. Fogg, Edwin J. Kroeger, and Frederick T. Weber — wheeled around and headed back to Ewa, landing around 1015 to find a far better reception that time around. Within a matter of minutes, the Marines began rearming and refueling Hilton's, Kroeger's and Weber's SBDs. The Marines discovered that Fogg's Dauntless, though, had taken a hit that had holed a fuel tank, and would require repairs. Although it is unlikely that even one of the Ewa Marines thought so at the time, even as they serviced the Enterprise SBDs which sat on the landing mat, the Japanese raid on Oahu was over. Vice Admiral Nagumo, already feeling that he had pushed his luck far enough, was eager to get as far away from the waters north of Oahu as soon as possible. At least for the time being, the Marines at Ewa had nothing to fear. Not privy to the musings of Nagumo and his staff, however, Lieutenant Colonel Larkin could only wonder what the Marines would do should the Japanese return. At 1025, he completed a glum assessment of the situation and forwarded it to Admiral Kimmel. While casualties among the Marines had been light — two men had been killed and several wounded — the Japanese had destroyed "all bombing, fighting, and transport planes" on the ground. Ewa had no radio communications, no power, and only one small gas generator in commission. He also informed the Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet, that he would retain the four Enterprise planes at Ewa until further orders. Larkin also notified Wheeler Field Control of the SBDs being held at his field. At 1100, Wheeler called and directed all available planes to rendezvous with a flight of B-17s over Hickam. Lieutenant (jg) Hilton and the two ensigns from Bombing Squadron 6, Kroeger and Weber, took off at 1115 and the Marines never heard from them again. Finding no Army planes over Hickam (two flights of B-17s and Douglas A-20s had only just departed) the three Navy pilots landed at Ford Island. Ensign Fogg's SBD represented the sole naval strike capability at Ewa as the day ended. "They caught us flat-footed," Larkin unabashedly wrote Major General Ross E. Rowell of the events of 7 December. Over the next few months, Ewa would serve as the focal point for Marine aviation activities on Oahu as the service acquired replacement aircraft and began rebuilding to carry out the mission of standing ready to deploy with the fleet wherever it was required.

|