|

ARKANSAS POST

The Arkansas Post Story |

|

Chapter 1:

FRENCH COLONIZATION AND ARKANSAS POST

By the mid-seventeenth century, European powers controlled substantial portions of North America. France occupied the St. Lawrence valley, Acadia and the Great Lakes region. England claimed much of the Atlantic Seaboard and Spain ruled what is now the southwestern and southeastern United States including the Gulf of Mexico. All three governments had designs on the vast unsettled interior of the continent. Although Spain extended a claim to this region by Hernando de Soto's expedition, she made no attempt at colonization. English explorers began to venture west of the Alleghanies and in 1673, two Virginians reached the Cherokees on the upper Tennessee River. Eager to compete with Spain and England for control of the great interior, the French government sponsored an expedition to this region in 1673.

Two capable men were chosen to undertake the expedition: Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit missionary, and Louis Joliet, a fur trader. On May 17 1673, Marquette, Joliet, and four other men departed Michilimackinack in two bark canoes. The tiny flotilla traversed Green Bay and the Fox River, portaged to the Wisconsin River, and, one month after initiating their journey, entered the "Great Father of Waters" described by Indians.

On March 15, 1674, Marquette and Joliet landed their bark canoes at the Quapaw Indian village of Kappa. The Quapaw were bewildered and perhaps frightened at the sight of these white-faced, bearded strangers—the first Europeans to come among them. To indicate his good intentions, Marquette smoked the calumet, the traditional pipe of peace, with tribal leaders. [1]

|

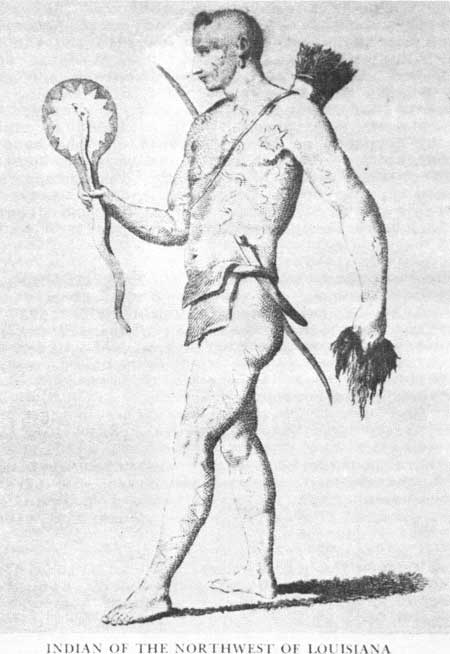

| Figure 1. Sauvage du Nord Ouest de la Louisiane. An unsigned, 1741 engraving. The Indian is probably a Quapaw warrior. He holds a scalp in one hand and a snake totem in the other. |

The Quapaw numbered about 2,500 individuals residing in four towns. Kappa and Tongigua were situated on the Mississippi River north of the mouth of the Arkansas River. Tourima and Osotouy were farther inland on the banks of the Arkansas River. Marquette and later travelers described the Quapaw as "strong, well made" and attractive in appearance, and dubbed them the beaux hommes or handsome men. The French found the Quapaw quite unlike northern Indians and characterized them as "civil, liberal, and of a gay humor." [2]

The Quapaw regaled their guests with two days of dancing and feasting. The Frenchmen learned from their hosts that the Mississippi River entered the Gulf of Mexico scarcely 10-days journey from Kappa. Fearing detection by the Spanish, however, the explorers did not follow the river to its mouth. Before departing the Quapaw, Marquette erected a great cross in their village as a symbol of friendship. Four months later the explorers brought news of their discoveries to Canada.

|

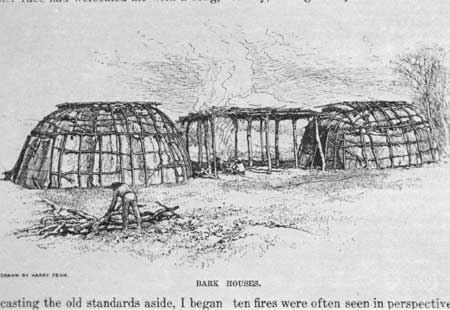

| Figure 2. Bark houses. The Quapaw lived in dwellings like these. The Century Magazine, Dec. 1895. |

The Marquette-Joliet expedition fostered dreams of an all-water route between the Great Lakes and the Gulf of Mexico. One energetic visionary in particular, Robert Cavalier Sieur de La Salle, developed an ambitious scheme to establish a chain of trading posts along the Mississippi from the lake country to the mouth of the river. [3]

La Salle was born in the city of Rouen, France, in 1643, to a wealthy burgher. At the age of 23 the young La Salle decided to seek his fortunes in the new world. In 1666, he traveled to the island of Montreal and obtained a seignuery or land grant. La Salle settled down to the life of a farmer, occasionally trading with the Indians. Stories of the great interior region related to La Salle by the Indians kindled his adventuresome spirit and awakened a desire for exploration. La Salle spent the next several years trading in the Ohio valley where he gained a thorough knowledge of the wilderness. When the young trader learned of Marquette's discovery of the Mississippi, he developed plans to establish a trading empire in the great interior. La Salle envisioned a chain of posts stretching from the lake country to the Gulf of Mexico. Each post would be operated by a trader. Furs obtained by the trader could be shipped upriver to Quebec or downriver to a town La Salle hoped to establish on the gulf coast. Of course, La Salle planned to reap a sizeable personal fortune for his efforts. [4]

In 1675, La Salle ventured to France to obtain the favor of the royal court for his plan. The influential young Norman managed to obtain a monopoly over the entire fur trade of the interior, the first step toward implementing his grand scheme. The following four years were spent in Canada making additional preparations. In 1678, La Salle was again in France to seek financial backing for his undertaking. While there he met Henri de Tonti, a personable young man recently discharged from the French army.

|

| Figure 3. Henri de Tonti, known to the Indians as "Tonti of the Iron Hand." Illinois State Historical Library. |

Henri de Tonti was born in Paris, in 1650. His Italian father had fled Naples with his family after taking part in an unsuccessful insurrection. De Tonti entered the French army at the age of 18, losing his right hand in the explosion of a grenade. The severed member was replaced with a metal hand that he disguised with a glove. Among the Indians, De Tonti's metal hand earned him a reputation as the possessor of powerful magic. Sometimes the willful explorer used it with great effect against rebellious Indians; for this he was widely known as "Tonti of the Iron Hand." De Tonti proved to be a fearless and loyal lieutenant to La Salle. Of De Tonti, La Salle remarked that "his energy and address make him equal to anything." [5]

In 1679, La Salle and his capable lieutenant succeeded in making alliances with the Illinois tribes and began construction of trading posts on the upper Illinois River. Iroquois incursions into the Illinois country, however, temporarily interrupted their mission. The English instigated attacks by this eastern confederacy of Indian tribes in the belief that they could force the Illinois to trade with England instead of France. The Iroquois totally demoralized the poorly organized Illinois Indians. In one raid, the eastern aggressors slaughtered or captured more than twelve-hundred members of one Illinois tribe. More than six-hundred were burned at the stake, and their roasted flesh consumed. Raids continued, and the Illinois abandoned their homeland, scattering westward for safety. Finally by 1681, La Salle succeeded in gathering many of these Indians together as a united front against the Iroquois. In August of that year, the explorer resumed his mission, leading an expedition down the Mississippi to discover the mouth of the great river. [6]

In March 1682, La Salle and his voyageurs arrived among the Quapaw Indians. Nearing the village of Kappa, the Frenchmen detected the faint, ominous beat of drums. Uncertain of the reception they would receive, the party crossed to the east side of the Mississippi and made camp. La Salle dispatched two Frenchmen to proceed to the village to act as hostages in declaration of his peaceable intentions. A few hours later, a delegation of Quapaw chiefs crossed the river, presenting the calumet or ceremonial pipe to La Salle. Now assured of the safety of his men, the cautious leader guided the party to the opposite shore. According to De Tonti, the Quapaw "regaled us with the best they had." The explorers received the same reception at Tongigua and Tourima. With the relationship between France and the Quapaw tribe thus reconfirmed, La Salle erected "the arms of the king" at Kappa and the voyageurs resumed their mission to discover the mouth of the Mississippi River. [7]

One month after leaving the Quapaw, the party reached the Gulf of Mexico. La Salle ceremoniously erected the "arms of the King," and claimed the entire Mississippi valley for France, calling it Louisiana in honor of the French monarch Louis XIV.

|

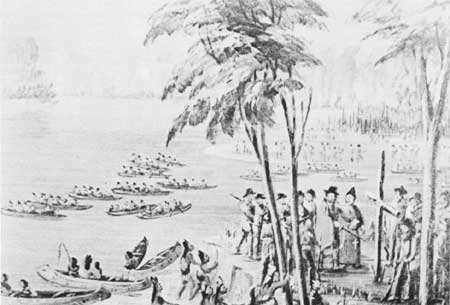

| Figure 4. La Salle exploring the Mississippi River. |

While ascending the Mississippi, the Frenchmen stopped once again among the Quapaw. La Salle granted to De Tonti, a large tract of land on the Arkansas River, the first land grant made in Louisiana. Apparently, La Salle foresaw the potential of the Arkansas area both for trade with the friendly Quapaw and as a stopping point for Mississippi River convoys. Someday, envisioned the explorer, the convoys would carry his furs to the gulf coast.

It appeared that La Salle's vision of a trading empire would soon be realized; only a town at the mouth of the Mississippi was needed. In 1683, La Salle returned to France to gather colonists and supplies for his projected town. In August of the following year the explorer departed France with two-hundred colonists in four ships bound for the Gulf of Mexico. Unfortunately for the expedition, the hapless fleet overlooked the mouth of the Mississippi during a violent storm. Because of an argument between the fleet captain and La Salle, the colonists were put ashore at Matagorda Bay, in present-day Texas. Seemingly undaunted by this setback, the intrepid explorer constructed a fort from which to explore the surrounding country and search for the Mississippi.

Problems plagued the ill-fated expedition from the start. Already responsible for a critical error in judgment that stranded his colony deep within Spanish territory, La Salle showed hesitancy and vacillation at critical moments. The leader alienated his men by his haughty bearing and lack of sympathy. In one particular instance, La Salle led a scouting party along the seacoast in search of the Mississippi River. Two brothers—remembered only by their surname, Langtot—accompanied the expedition. When the younger Langtot lagged behind the procession, La Salle angrily rebuffed the man, and ordered him to return forthwith to camp. As he retraced his steps, alone, the helpless Langtot was murdered by Indians. Blaming La Salle for the incident, the elder Langtot "vowed to God that he would never forgive his brothers death." [8] This incident proved to be La Salle's undoing.

|

| Figure 5. La Salle among the Quapaw at the mouth of the Arkansas River. |

In January, while on another scouting mission, Langtot avenged his brothers death. With several partisans he had enlisted to his cause, Langtot volunteered to venture ahead of the main party in search of three overdue hunters. La Salle granted the request. Langtot soon found the missing hunters who had stopped to dry the meat of a buffalo they had killed. Since dusk approached, the group made camp. Langtot convinced the three hunters, whom he knew were loyal to La Salle, to take the first watch. After fulfilling their responsibility, all three men were murdered in their sleep. As dawn approached, the camp was aroused by the sound of shots, a signal that La Salle approached. Langtot and his mutinous cutthroats scattered to the woods and encircled the camp. The unsuspecting La Salle walked directly into their midst. Spying only a servant, La Salle asked the man of the whereabouts of the others. A tense silence greeted the request. Suddenly, the forest exploded with the sharp report of pistols. La Salle "received three balls in his head" and slumped to the ground. [9] Thus ended the life and ambitions of Robert Cavalier Sieur de La Salle. Months later when De Tonti learned of the murder, he characterized his former captain as "a man of wonderful ability and capable of undertaking any discovery." [10] The Matagorda Bay colony dissolved. One group abandoned the fort and undertook the long trek to Canada. Those who remained met death at the hands of the Indians or became captives of the Spaniards.

During the time that La Salle attempted to establish a colony at the mouth of the Mississippi, De Tonti remained in the Illinois country to look after affairs there. In 1686, De Tonti learned that La Salle was somewhere on the gulf coast and set out to find his leader. A search party led by De Tonti reached the mouth of the Mississippi in April. Following an extensive but fruitless search, De Tonti abandoned his effort to find La Salle. Retracing their steps, the searchers stopped at the seignuery or land grant on the Arkansas River given to De Tonti by La Salle four years earlier. Ten of the voyageurs accompanying De Tonti requested permission to remain on the seignuery and open a trading post among the Quapaw. Fortunes in peltries could be amassed here by an enterprising trader. De Tonti granted the request to six of his men, placing them under the leadership of Coutoure Charpenter. The remainder returned with De Tonti to Illinois to procure supplies and trade goods for the venture. [11]

Charpenter and the five remaining Frenchmen set about constructing the trading post. As a suitable location, a small prominency scarcely "half a musket shot" from the Quapaw village of Osotouy was selected. This promised to be a suitable site for the post because of its proximity to prime beaver country about eighteen miles above the mouth of the Arkansas River. Charpenter's men erected a house after the "French fashion." The structure was a small cabin of horizontal "cedar" logs joined at the corners by "swallow-tail" notches. The roof was covered with bark. [12]

De Tonti planned to develop this post and turn it into a permanent French settlement. Realizing the importance of a mission to the growth of his seignuery, De Tonti deeded to Father Dablon, superior of the Canadian missions, two tracts of land for missions to serve the French and Indians. The resident missionary would be expected to share his time ministering among the French and Quapaw. De Tonti somewhat presumptuously styled himself "Seignor [sic.] of the City of Tonti and of the river of Arkansas." The clergy never took advantage of his generous offer, and the "City of Tonti" was never more than a tiny trading post in a trackless wilderness. [13]

In July 1687, several survivors of La Salle's ill-fated Matagorda Bay colony stumbled upon De Tonti's post. This group, led by Henri Joutel, had separated from La Salle's assassins and begun the grueling journey to Canada. After nearly six months of wandering through the wilderness, Joutel and the other survivors stood on the bank of the Arkansas River. To their joy, a great wooden cross and a French house were on the opposite side. The tattered travelers "knelt down, lifting up . . . hands and eyes to heaven" and gave thanks to God for their salvation. [14]

The traders at De Tonti's post were no less overjoyed to find other Frenchmen in these remote quarters. Spying Joutel's party, already being escorted across the river by some Quapaw Indians, two Frenchmen rushed out of the post and in their excitement fired a salute with their muskets. Joutel wrote that they "had almost as much need of our help as we of theirs since they had neither powder nor shot nor anything else." [15] Trade items for the Quapaw had been slow in coming, and four of the six men whom De Tonti had left on the Arkansas, had returned to the Illinois country. The remaining men, Coutoure Charpenter and one known only as De Launey, lacked trade items to pacify the Indians and were in a vulnerable position.

Following the excitement of their arrival, Joutel's party recuperated at the post for several days. To alleviate the problems of their hosts, the refugees provided Charpenter and De Launey with their remaining trade goods including 16 pounds of powder, 800 balls, 300 flints, 26 knives, 10 axes, and 2 to 3 pounds of beads. Exchanging their horses to the Indians for canoes, Joutel and his men resumed their journey. As an additional service, Joutel transported a small bundle of beaver pelts that the traders had managed to purchase from the Quapaw. A Parisian referred to as Bartholomew, being "none the ablest of body," was left at the post to recover. [16]

Joutel's party reached the Illinois country and informed De Tonti of La Salle's murder. Having learned of the mutiny, De Tonti organized a second expedition to search for remaining survivors of the Matagorda Bay colony. Only seven days march from the Spaniards, however, De Tonti's voyageurs would search no further. Disgusted with the lot, he described them as "unmanageable persons over whom I could exercise no authority." De Tonti was forced to abandon his search. [17]

|

| Figure 6. The location of Arkansas Post from 1686-1698. Henri de Tonti established a trading house on the Arkansas River to trade with the Quapaw Indians. |

While among the Quapaw, De Tonti visited his "commercial house" for the first time. To reach the post, the explorer found it necessary to navigate 18 miles up the Arkansas around numerous sandbars and through swift currents. The inconvenience of reaching the post was evident. During his next visit eight years later, De Tonti had the season's beaver catch delivered to him at the mouth of the Arkansas. [18]

The trading establishment on the Arkansas River was doomed to failure. For many years, there had been difficulty in marketing beaver in Europe. Such a large surplus of pelts had accumulated that the French monarch placed a moratorium on beaver trade south of Canada and ordered all voyageurs to return to Quebec. These restrictions led to misfortune in De Tonti's trading ventures. In 1698, De Tonti traveled to the Arkansas under government service to enforce the royal edict and evict all French hunters and traders. This action probably led to the desertion of Coutoure Charpenter, trader at De Tonti's Post.

Charpenter joined the English in the Carolinas where trade was unrestricted. In 1700, the renegade Frenchman guided a party of Englishmen to the mouth of the Arkansas to trade with the Quapaw. The attempt was foiled, largely because of the timely intervention of Pierre Charles le Seurer, a French explorer. Le Seurur informed the interlopers of the claim of France to the region.

Because of the depressed economy and English overtures to control the Louisiana fur trade, the French government relied on missionaries to preserve goodwill and maintain alliances with the Indians. In 1698, De Tonti guided several Jesuits downriver to locate sites for missions. Two years later, a Jesuit, Father Nicholas Focault, decided to live among the Quapaw.

The first Arkansas mission was short-lived. Father Focault's contemporaries believed him too infirm to be a missionary. Predictably, the priest's efforts among the Quapaw met with little success. Greatly discouraged, Focault abandoned the mission after one year. The priest bargained with some Coroa Indians to accompany him and two French soldiers from Illinois to Mobile, the capital of Louisiana. Perhaps from motives of robbery, the Coroa Indians fell upon the Frenchmen while in-transit, slaying all three of them. The perpetrators vanished into the forest, eventually taking refuge among the Yazoo Indians with whom they shared their booty.

Father Antoine Davion discovered the scene of the massacre while traveling to the Arkansas to visit Focault. Shocked by the gruesome spectacle, Davion buried the bodies and hastened to Mobile to recount the tragedy to Governor Jean Baptiste Lemoyne Bienville. Outraged by the heinous act of violence, Bienville urged the ever-faithful Quapaw to punish the Coroa. As a result of the Quapaw reprisals, the Coroa were nearly exterminated. [19]

The Arkansas mission failed. Many years would pass before a "black robe" walked among the Quapaw again. As far as French settlement is concerned, there is little record of activity on the Arkansas from 1702-1721, indicating that the area may have been abandoned. [20]

|

| Figure 7. Indian taking a scalp. From Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs and Condition of the North American Indians by George Catlin. Figure 7. Indian taking a scalp. From Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs and Condition of the North American Indians by George Catlin. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

arpo/history/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 13-Feb-2006