|

ARKANSAS POST

The Arkansas Post Story |

|

Chapter 2:

THE LAW COLONY

The Province of Louisiana had not prospered under government organization. French officials realized that to cope with British competition and to benefit from her discoveries, that colonies must be established. In 1712, Antoine Crozat accepted a 15-year charter, essentially a trade monopoly, under the condition that he colonize Louisiana. Crozat's plans never materialized. French commercial laws, low fur prices, and the trade monopoly crippled the province. In 1717, the responsibility to colonize Louisiana passed from Crozat to John Law, wealthy financier and director general of the Royal Bank of France. [1]

John Law was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1671. Little is known of Law's early life, but at the age of 23, the young Scot was in London where he killed a man in a duel. Condemned to death for his actions, Law escaped to the continent and lived the roving life of a gambler. During his nefarious career, Law developed his financial genius and pioneered the concept of issuing paper currency. In 1716, Law founded the private Bank General in France. Because of his financial success, the French government appointed Law director general of the Royal Bank of France and offered him a 25-year charter for the Louisiana fur trade. Law received commercial and political control of Louisiana and, in return, promised to colonize the province. To administer Louisiana, Law formed Companie d'Occident, which became known as Companie des Indies after Law's acquisition of the Indies trade in 1719. [2]

John Law's scheme to colonize Louisiana was ambitious. Extensive tracts of land, known as concessions, were granted to individuals who agreed to bear the cost of colonization. With settlers in high demand, many emigrants were secured from overcrowded European jails and hospitals. Great numbers of slaves were imported, thus laying the foundation for an agricultural economy. In 1718, New Orleans was laid-out, and Fort Chartres established to protect the growing French population in the Illinois Country. During the same year, plans were formulated to establish a concession between Illinois and lower Louisiana to facilitate trade and communication between both growing population centers. In turn, Mississippi River convoys would create a ready market for products of such a concession. The potential of an intermediate station was so great that shrewd entrepreneur John Law reserved this concession for himself. Law needed a suitable location roughly equidistant between both population centers. The site of De Tonti's former trading post proved ideal. [3]

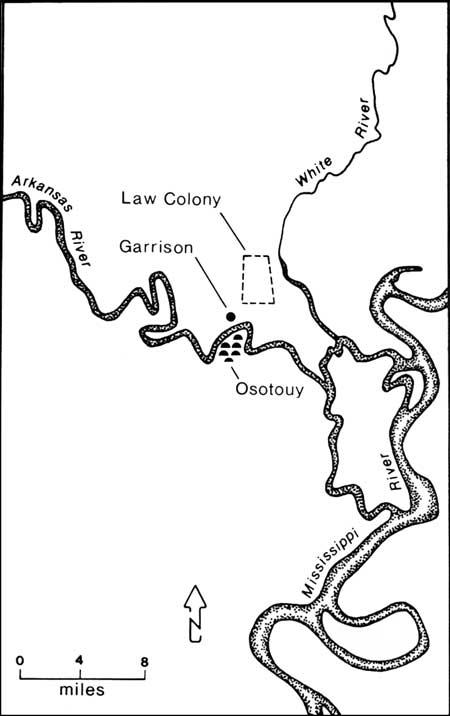

John Law appointed Jacques Levens as manager and trustee of his concession. In August 1721, Levens and about fifty French colonists took possession of the tract. Approximately two-hundred German farmers were expected to arrive in the following months. Levens established the colony on a "beautiful plain surrounded by fertile valleys and a little stream of fine clear wholesome water." Lieutenant La Boulaye and a garrison of 17 soldiers arrived on the Arkansas to protect the civilians, the growing river commerce, and trade with the Quapaw. The garrison occupied a site at Ouyapes, a Quapaw village near the mouth of the Arkansas, some eighteen miles down-stream from the Law Colony. From this vantage point, troops could control Mississippi River traffic and be within reach of the colonists should they require protection. [4]

Meanwhile, the "Mississippi bubble," as Law's scheme to develop Louisiana was called, burst! The overissue of paper currency to support the colonization of the province caused the ruin of Law's financial empire. The former banker left France in shame and his estates were confiscated. The colonial enterprise was discredited, and investment capital ceased to flow. Companie des Indies, under new management, was forced to seek different sources of revenue. The only assets left, however, were the fur trade and the possibility of opening commerce with the Spanish southwest. [5]

Rumors of gold and silver mines in Spain's southwestern provinces circulated widely. If a route could be found that linked Louisiana to the southwest, Companie officials reasoned, the Louisiana venture could finally reap a profit. To explore the possibility of using the Arkansas River as a route to the southwest, the Companie commissioned Benard de la Harpe to undertake an expedition.

Torrential rains and flooding along the Arkansas River plagued the colonists and soldiers during their first year on Law's concession. When La Harpe arrived on the Arkansas on March 1, 1722, he found Lieutenant La Boulaye and Second Lieutenant De Francome living at the Quapaw village of Osotouy. Initially, La Boulaye had located the garrison on the Mississippi River, but because of high water, moved it one month later to a site about eighteen-miles upriver. A single soldier, Saint Dominique, remained at the former location to await the arrival of delinquent trade goods. La Harpe found the new post scarcely deserving of notice. Lieutenant Jean Benjamin Francois Dumont, scientist for the expedition, commented that "there is no fort in the place" at all. Improvements consisted of "only four or five palisaded houses, a guard house and a cabin which serves as a storehouse." Concerning the remainder of the garrison, La Boulaye explained that they were sent to the Law colony to assist the inhabitants in cultivating their fields. [6]

On March 2, La Harpe proceeded to the concession approximately one and one half miles west-north-west of the post. Here he discovered about forty seven persons in all. The two hundred Germans slated to occupy the concession had learned of Law's failure and settled instead on Delaire's grant in lower Louisiana. [7] The season had been so wet on the Arkansas that the colonists were unable to raise a crop or even trade for provisions from the Indians who saved not even enough corn for the next season's planting. Few improvements had been made over the course of a year, and La Harpe sadly noted that "their works still consist of only a score of cabins poorly arranged and three acres of cleared ground." [8]

La Harpe remained at the colony until March 10, long enough to barter for supplies from the Indians and register colonists for the Companie. Dumont spent his time laying out streets, along which permanent houses could be built. Departing the colony, the explorers ascended the Arkansas River and devoted a number of days to making scientific observations. Because of low water, however, the party ended its ascent somewhere in the vicinity of Cadron Creek. La Harpe landed once again at Law's concession only to find that the majority of the colonists had "gone down the river." Ironically, the departing Frenchmen narrowly missed a supply boat dispatched from New Orleans. Lamenting the failure of the enterprise, La Harpe wrote that it was "a very great injury, this concession being absolutely necessary to this post, for the help in provisions that it will furnish to the convoys, destined for navigation of this river." [9] At least a few Frenchmen, however, did remain on the concession.

Deron de Artaquette, an official of Companie des Indies, visited the concession a year later. While at the faltering colony, he observed: "only three miserable huts, fourteen Frenchmen and six negroes whom Sr. Dufresne, who is the director there for the company employs in clearing the land. Since they have been on this land they have not even been able to raise Indian corn for their nourishment, and they have been compelled to trade for it and send even to Illinois for it." De Artaquette visited the garrison later the same day and found that the post contained a "hut for Commandant La Boulaye and a barn which serves as lodging for the soldiers stationed there." [10]

Unimpressed by the developments De Artaquette found on the Arkansas, Companie des Indies officially abandoned the concession in 1726. Governor Bienville ordered partial evacuation of the post recommending that a garrison of eight men remain to maintain an alliance with the Quapaw. Because of spiraling costs and a depressed fur trade, the French government relied once again on missionaries to preserve the goodwill of Indians. In 1726, the year the garrison abandoned the post, the French government contracted with the Jesuits to send a priest to the Arkansas to minister to the Quapaw and 14 remaining Frenchmen.

|

| Figure 8. The location of the John Law Colony and Arkansas Post from 1721-1726. In 1721, wealthy financier John Law established a colony in the vicinity of De Tonti's former trading house. |

In 1727, Father Paul du Poisson, a Jesuit, took up residence at the failed concession. Selecting the house of the former commander as his rectory, Du Poisson began his ministry. Among the remaining colonists were three married men (Pierre Douay, Baptiste Thomas, and one called St. Francois) and eight bachelors (Poiterin, Montpierre, Jean Mignon, Jean Hours, Jean le Long, Bartelemias, and Du Fresne). For ministering to his tiny flock, Du Poisson received a stipend of 800 livres, a sum barely adequate for the support of a mission in the wilds of Arkansas. Later in the year, Brother Crucy joined Du Poisson to assist in the ministry. Brother Crucy, however, died of sunstroke two years later, forcing Du Poisson to leave the Arkansas in search of additional support. The unfortunate priest was caught at Fort Rosalie during the Natchez Indian massacre of 1729. Reportedly, Du Poisson was beheaded while kneeling at the chapel alter. For a second time, the Arkansas mission failed. [11]

Angered with French occupation of their lands, the Natchez Indians had set out to exterminate the French. These Indians lived in several towns near the present-day city of Natchez, Mississippi. The tribe numbered about six-thousand, and was able to put between one-thousand to twelve-hundred warriors in the field. The Natchez offensive culminated in the debacle at Fort Rosalie where 250 Frenchmen were murdered and countless numbers of women and children were carried off into captivity. It was this massacre that claimed the life of Father Paul du Poisson and ended the Arkansas mission. In retaliation, the French government waged a two-year campaign against the Natchez. In 1731, with the aid of the Choctaw Indians, the French nearly exterminated this formerly powerful nation. The surviving Natchez fled to the Chickasaw nation, enlisted the aid of their hosts, and continued to harass the French. [12]

Companie des Indies, having borne the expense of the Natchez conflict, decided that Louisiana would never be a paying investment. The Companie was, therefore, released from its charter, and Louisiana became a royal province once again. Ironically, the resident French population on Law's former concession, attracted by the abundance of the Arkansas region, had more than doubled.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

arpo/history/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 13-Feb-2006