|

CABRILLO

The Guns of San Diego Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER 8:

ROADS, STATUES, CEMETERIES, AND FORT ROSECRANS

A. Roads

The construction of a lighthouse on Point Loma in 1854 caused the first crude road to be built to the top of the peninsula. Eighteen men worked for thirty-five days to carve out the road from Ballast Point to the lighthouse site. Today a road crawls up the slope from the south end of Ballast Point to the top of the ridge, possibly on the alignment of that first road. In order for the keepers to haul in fresh water and supplies, the Congress appropriated $1,500 to build a road from La Playa along the Point Loma ridge to the lighthouse, which was built in 1857. [1]

When army engineers began construction of the Endicott batteries at Ballast Point in 1897, they found the roads on Point Loma in terrible condition. Col. Charles R. Suter wrote that it was necessary to construct a road along the harbor shore from a wharf at La Playa to Ballast Point and beyond to Billy Goat Point. From there one branch should climb up the slope to the old lighthouse, while another would continue on to the south end of the peninsula. The old road from Ballast Point, built by the lighthouse contractor forty years earlier was in need of reconstruction. Also, the road along the ridge needed strengthening for the hauling of ammunition. Because the engineers did not construct proposed batteries at Billy Goat Point and on top of Point Loma at this time, the colonel's recommendations were not carried out, with the exception of a rough road from La Playa to Ballast Point, the predecessor of Rosecrans Street. [2]

In 1908 the Chief of Engineers learned that the City of San Diego had begun construction of a 100-foot-wide boulevard around the upper end of San Diego Bay and which led toward the naval reservation and Fort Rosecrans. The local army engineer considered it advisable that the new road should be continued through Fort Rosecrans. Such a road would be of great value in time of war, "as well as affording conveniences of travel for visitors, the majority of whom desire to go to the top of the peninsula near the southerly end where the view in all directions is extraordinarily fine." The Army's Quartermaster General caused such a road, three miles long and surfaced with decomposed granite, to be constructed out to the old lighthouse in 1910 at a cost of $30,000. [3] It is an extension of Catalina Boulevard and is now known as Cabrillo Memorial Drive.

The construction of searchlights 5 and 6 and their power plant near Billy Goat Point in 1918-1919 led to the building of a road "merely graded, without surfacing" from Ballast Point to Billy Goat Point. From the point a trail continued on curving up the hill to the old lighthouse. In the beginning the road was called Meyler Road, in honor of 1st. Lt. James J. Meyler, the engineer who built the first Endicott batteries at San Diego. Later it was named Sylvester Road in honor of 1st Lt. William G. Sylvester, the first coast artillery officer killed in action in WW II, at Hickam Field, Hawaii on Dec 7, 1941. For the same reasons, a dirt road was constructed from the northern part of the reservation south along the west side of the peninsula to the new lighthouse, now known as Cabrillo Road. The cost of both roads was estimated at $3,000 per mile. [4]

In 1933, the year the Army transferred Cabrillo National Monument to the Department of the Interior, the Secretary of War gave permission to the State of California to extend and maintain a state road through the military reservation to the old and new lighthouses. Dedicated on July 24, 1934, this road has been named Cabrillo Memorial Drive. [5] Also in 1934, the post commander, Col. George Ruhlen, had the trail from the old lighthouse to Billy Goat Point widened into a road that tied into Meyler Road, thus creating a loop on the eastern half of the peninsula. In 1974 the Navy declared a portion of the loop road surplus and it was added to Cabrillo National Monument. Known today as the Bayside Trail, the old oiled road and its military and natural history have been incorporated into the monument's interpretive program. [6]

B. Statues

In 1892, on the occasion of the 350th anniversary of Cabrillo's discovery of San Diego Bay, the citizens of San Diego and Southern California celebrated "Discovery Day" on September 28-30. Parades, boat races, Indian demonstrations, a reenactment of Cabrillo's coming ashore, banquets, and a grand ball marked the festive occasion. The Sun newspaper thought that the successful affair should be made an annual event. The San Diego Union, meanwhile, advocated a monument to Cabrillo, perhaps a pile of rough boulders on the crest of the hill in the city park. But the time was not ripe for either a holiday or a monument. [7]

As San Diego prepared to hold the Panama-California International Exposition scheduled for 1915, a local group, the Order of Panama, planned to construct a 150-foot statue on the Army's Point Loma. For that purpose President Woodrow Wilson signed a proclamation establishing Cabrillo National Monument on October 14, 1913. The land consisted of the half-acre on which the old lighthouse stood. The Order of Panama planned to demolish the lighthouse and build the statue on the site. Despite the enthusiasm with which this movement began, detailed plans were not prepared. Attention turned to the exposition. When the successful fair ended, the Order of Panama disbanded. The Native Sons of the Golden West next became interested in a monument to Cabrillo on Point Loma, in 1926. But when efforts to raise funds failed, hopes dashed and interest disappeared. [8]

The Portuguese government originally commissioned Alvaro DeBree to create a statue of Cabrillo for exhibition at the 1939 New York World Fair. Too late for New York, the fourteen-foot statue arrived in San Francisco for that city's 1940 world fair. The damaged statue never got to the fair but ended up in a private garage in San Francisco. Col. Ed Fletcher, a state senator from San Diego, believed that the statue should come to San Diego. Governor Culbert Olson, however, promised the statue to the city of Oakland where a large number of Portuguese had settled. Fletcher persuaded the owner of the garage that he had the authority to remove the statue and took it to San Diego before Governor Olson could object. At San Diego the statue was placed at the west end of the Naval Training Center where it stayed through World War II. [9]

In 1949 the City of San Diego paid to have the seven-ton statue moved to Cabrillo National Monument where it was rededicated on September 28 at a site near the lighthouse. [10]

|

| Statue of Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, Cabrillo National Monument. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

|

| Old Point Loma Lighthouse, Cabrillo National Monument, in service from 1855 to 1891. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service. |

A 150-foot Cabrillo statue sprang into the news once again in 1967, when San Diego Mayor Frank Curran announced a plan to construct one at Cabrillo National Monument, a west coast version of the Statue of Liberty. After considerable debate and delay, the National Park Service objected to the huge size of the projected statue. A proposal was developed for a much smaller statue, but Mayor Curran was not impressed. For the third time, the concept of a 150-foot statue faded away. [11]

In 1959 President Dwight Eisenhower signed a proclamation transferring approximately eighty acres of former Fort Rosecrans land to Cabrillo National Monument. This vast increase in acreage allowed the National Park Service to plan a huge increase in visitor services and interpretation of the historic lighthouse, Cabrillo's discoveries, and the natural history of the monument. The museum in the new visitor center told the story of Cabrillo's voyage. Nearby is a magnificent overlook that commands views of the ocean, North Island, San Diego Bay, the city, and the mountains. The National Park Service moved the Cabrillo statue from the lighthouse to this dramatic site in 1966. A concrete structure at this site had to be removed to make room for the statue.

The original statue, carved from a porous, stratified limestone and broken, even before it came to the monument, suffered in the maritime air in the years since its arrival. In the 1980s steps were initiated to have an exact duplicate of the statue carved by a Portuguese sculptor, Joao Charters Almeida, from harder stone. The original statue was carefully removed and placed in permanent storage. The duplicate work was installed amid ceremonies involving the Portuguese and Spanish governments in February 1988. The gleaming white statue continues to command the magnificent vistas that greeted Cabrillo so many years ago. Carved on the front of the imposing statue is "Joao Rodrigues Cabrilho," on the reverse, "Joao Rodrigues Cabrilho, Descobridor California 1542," and the name of the original sculptor, "Alvaro DeBree, 1939, Lisboa." A new plaque, a tribute from the Portuguese Navy, has been emplaced near the base of the statue. Spain's navigator, who died in California's lands, is thus commemorated at Cabrillo National Monument. [12]

C. Fort Rosecrans National

Cemetery

When Pvt. John T. Welch, 8th Infantry, died at San Diego Barracks in 1879, his remains were buried on the crest of the military reservation at Point Loma. The Army named the one-acre burial place "Post Cemetery, San Diego Barracks (Point Loma)." In 1888 the remains of the eighteen First Dragoon soldiers killed in the battle of San Pasqual in 1846 were removed from a civilian cemetery in San Diego and reburied in the post cemetery, the gravesite marked "Unknown." The Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West rectified this in 1922 when they placed a granite boulder taken from the San Pasqual battlefield on the site. A bronze plaque affixed to the boulder listed the eighteen names. When Fort Rosecrans was established in 1899, its name was applied to the cemetery. [13]

As the Navy's and Marine Corps' activities increased in San Diego, these services used the cemetery for their dead. When an explosion tore apart the boiler room of USS Bennington in San Diego Harbor in 1905, one officer and sixty-five of the crew lay dead. The Navy interred the remains of thirty-five sailors in the post cemetery. The officers and men of the Pacific Squadron erected a seventy-five-foot high granite obelisk "to the Memory of Those Who Lost Their Lives in the Performance of Duty." [14]

By 1913 space had become a rarity in the cemetery, so much so that the Quartermaster General asked the War Department for funds to enlarge the area. Funds were not available, nor were they a year later when the post quartermaster submitted a requisition for $1,320 for a wrought-iron fence to be placed around the cemetery. [15] In 1915 the post commander, Lt. Col. W. C. Davis, recommended that the cemetery be enlarged to twice its size, a caretaker employed, a lodge built for a superintendent, and that legislation be secured designating it as a national cemetery. His recommendations went unheeded. [16]

Affairs reached a crisis in 1932 when an inspector general visited Fort Rosecrans. He inspected the cemetery and found it to be in excellent condition. But the available space would be filled by the end of the year. The average annual rate of internments over the past five years had been nineteen, and but twenty-one plots remained in the enlisted section. The officers' section, however, still had sufficient space for some time to come. At that time the Army was considering abandoning Fort Rosecrans, thus the Inspector General recommended that the post cemetery be made a national cemetery. Upon receipt of these remarks, the War Department decreed that the cemetery would not be enlarged, but that only army personnel could be buried there. The Quartermaster General so notified the Chief of Naval Operations. [17]

A more permanent solution was achieved in 1934 when War Department General Orders No. 7 designated eight acres of Fort Rosecrans as Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery. Since then additions to the cemetery have brought its size to seventy-one acres. Even so, in 1966 the Army announced that the national cemetery was closed to internments "except for those in reserved gravesites". [18]

In 1973 the Department of the Army transferred jurisdiction of the national cemetery to the Veterans Administration. Grave markers identify seven men awarded the Medal of Honor: Brig. Gen. Ross L. Winans, U.S. Marine Corps; Capt. Willis W. Bradley, U.S. Navy; Lt. John E. Murphy, U.S. Navy; Lt. Cdr. William S. Cronan, U.S. Navy (USS Bennington); Ens. Herbert C. Jones, U.S. Navy (killed at Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941); S. Sgt. Peter S. Connor, U.S. Marine Corps (Vietnam); and Sgt. Anund C. Roark, U.S. Army (a memorial marker; his body was not recovered in Vietnam). There are 158 additional memorial markers for men whose remains were not recovered, or identified, or who were buried at sea. Every day the flag of the United States flies twenty-four hours. [19]

D. Fort Rosecrans

World War II developments such as long-range missiles and the atomic bomb rendered the traditional coastal defenses obsolete. Amphibious warfare, especially as it was developed in the Pacific, made it unnecessary to capture an enemy's ports when invading his territory. The demise of the Harbor Defenses of San Diego came swiftly. In March 1947 Fort Rosecrans was placed in a caretaking status with a garrison of 101, which number would further decline. The Department of the Army ordered the forty-nine-year-old fort to be a subinstallation of Fort MacArthur at Los Angeles effective December 1, 1948. The Harbor Defenses of San Diego were formally discontinued on January 1, 1950. [20]

The Department of the Army transferred Fort Rosecrans to the Department of the Navy in May 1957. The army, however, did not leave the installation until March 1959 and the Navy occupied the fort in June:

On Wednesday, San Diego's Fort Rosecrans will end its long career as an Army post. The fort's Regular Army detachment of one officer and four enlisted men will turn the 557 acre post over to Navy maintenance personnel, and for the first time in 61 years, the old harbor bastion will be without a garrison. There will be no ceremonies... [21]

The U.S Navy had first come to Point Loma in 1904 when the War Department transferred the north end of Fort Rosecrans to the Navy for a coaling station and, in 1906, a naval radio station. Point Loma Naval Reservation today has a Submarine Base, Degaussing Station, Naval Supply Center, Fleet Combat Training, and the Naval Ocean Systems Center (NOSC), which "is a major contributor of communications and electronics data applicable to the Navy's fleet operations. [22]

The 16-inch-gun Battery Ashburn now houses a micro-electronics laboratory, while 12-inch-mortar Battery Whistler is home to the Arctic Submarine Research Laboratory. The Navy uses 6-inch-gun Battery Woodward as a radio facility. Both 8-inch-gun Battery Strong and the former Harbor Defense Command Post contain communications systems laboratories. The Navy has installed offices and a Naval Reserve HECP in 6-inch-gun Battery Humphreys. The Submarine Base has adapted 12-inch-mortar Battery John White for use as shops and storage, and 3-inch-gun Battery McGrath for use as an explosives magazine. Battery Calef-Wilkeson's magazines are currently used for storage by the Naval Submarine Base. Many of the Fort's original barracks and officers' quarters are used by the Submarine Base as offices and quarters. Fort Emory at Imperial Beach was transferred to the Navy in 1947 as part of the Naval Radio Station which had been established there in 1920. In a different way, the harbor defenses of San Diego continue to exist. [23]

|

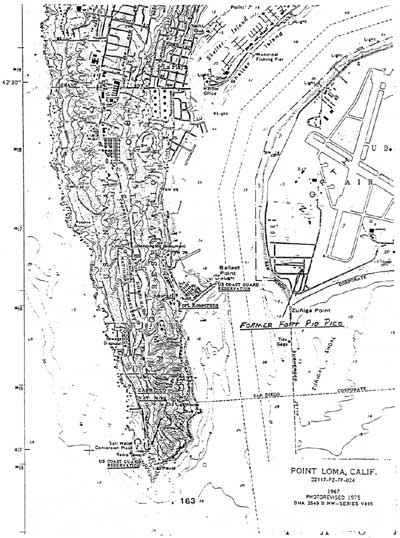

| Point Loma today. Cabrillo National Monument shares the peninsula with the City of San Diego, the U.S. Coast Guard, and the U.S. Navy. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

cabr/guns-san-diego/chap8.htm

Last Updated: 19-Jan-2005