|

Cane River Creole National Historical Park Louisiana |

|

NPS photo | |

Colonial Roots

Genesis of a Culture

A vital branch of the New World culture we know as Creole took root in the rich soil along Cane River in 18th-century Louisiana. It was a culture nurtured by French and Spanish colonial ways, steeped in Africanisms, and enriched by American Indian contact. Its survival for nearly three centuries, depicted in the stories of the LeComtes, Hertzogs, Prud'hommes, and other families, testifies to a resilient community founded on deep attachments to Catholicism, family, and the land.

In 1725 Catherine Picard, daughter of a New Orleans trader, married Jean Pierre Philippe Prud'homme, a former marine and trader from Natchitoches. The French-born couple returned to the rough-hewn military and trading post—an open crossroads world where cultural exchanges and marital unions among French, Spanish, French Canadian, African, and American Indian cultures were producing a dynamic frontier society with a distinctive French accent. Ex-soldiers like Prud'homme moved out from the post to make a living as traders, hunters, and farmers along the Red River, known in this area as Cane River. As indigo and tobacco farming supplanted other livelihoods, colonists relied more heavily on the enslaved African workers who had helped build the colony.

Among the tobacco farmers was Jean Baptiste Lecomte, who in 1753 obtained a land grant on Cane River. From this seed grew Magnolia plantation. In 1789 Prud'homme's grandson Jean Pierre Emmanuel also received a land grant on the Cane, the core of Bermuda—later renamed Oakland—plantation. After the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, he and LeComte's son Ambroise turned to the crop that forever defined the region.

King Cotton

The Prosperous Years

In the decades after the United States took possession of Louisiana in 1803, the cotton culture reached its zenith. Built on slavery, it was underpinned by an agrarian ethic of self sufficiency and land stewardship exemplified by Emmanuel Prud'homme. In 1821 his enslaved workers built his house on land he named Bermuda. Creole families like the Prud'homme, and LeComtes solidified their positions by expanding their holdings and marrying into each other's families. In 1852 Ambroise LeComte II's daughter Atala married Matthew Hertz and Magnolia plantation passed to the couple and their descendants.

This Creole society combined hard practicality demanded by frontier life with Old World joie de vivre and spirited celebration of the rituals of daily life and Catholicism. The French-speaking enslaved workers had created their own rich culture centered around the church, family ties, and preserved African traditions. Yet even as the Creole culture evolved, it underwent a gradual but profound change. Anglo-American poured into the region, bringing their English language, Protestant religion, and their own African American enslaved workers. Life grew more constricted for non-whites, as U. S. laws removed colonial-era rights such as self-emancipation by purchase, and gens de couleur libre lost the special status they had enjoyed under French rule.

In the face of change Creole planters clung fiercely to their culture while embracing new technology. In the 1850s Phanor Prud'homme installed one of the area's, earliest steam cotton presses. Neither the press nor the Prud'homme fortune would survive the coming storm.

Civil War

Ruin and Rebirth

The fires of civil war transformed life on Cane River. As the Union blockade of New Orlean cut off cotton markets, the Confederate army commandeered slaves and grain. In the Red River campaign southern troops burned the planter's cotton before the North could seize it. Retreating Union troops left burning plantations in their wake, including Magnolia's main house and the gin barn at Bermuda. At war's end Phanor Prud'homme's sons Alphonse and Emmanuel II, who had both fought for the Confederacy, inherited Bermuda and divided it, Alphonse naming his part Oakland. Well-run plantations, like Magnolia and Oakland survived the war, but low prices and boll weevils brought mostly lean times until World War I.

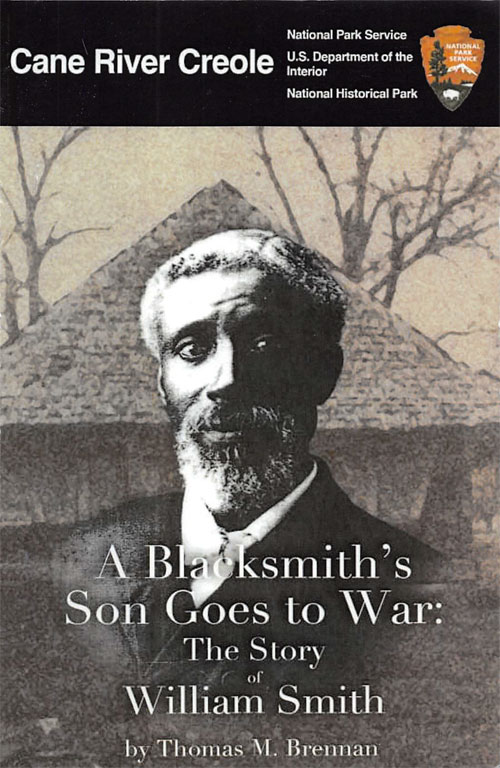

For the plantation workers freedom brought new trials, such as Freedmen's Bureau labor contracts whose condition differed from slavery mainly in that they required the worker's consent. Artisans like Bermuda's blacksmith Solomon Williams could negotiate their own contracts for pay and hours. For those without specialized skills the only alternative to the Freedmen's contract was to accept sharecropping arrangements. These ranged from a relatively benign feudalism to virtual bondage, with the chains of slavery replaced by endless debt to the plantation store.

Many workers left the region, but others stayed and eventually rebuilt a strong community around church and family, often within the same quarters that had housed their enslaved ancestors. The region grew less isolated, but some older planters and workers spoke French into the 20th century.

Old Ways Pass

Migration and Modernization

Oakland and Magnolia enjoyed a brief revival in 1914 as World War I increased cotton demand, but prices fell again and hard times returned. The Great Migration of African Americans began in 1916 as workers displaced from failing plantations moved north for war-related jobs. Then a downward spiral of overproduction and falling prices brought depression to the region a decade earlier than the rest of the country. As they had during the Civil War, Oakland and Magnolia became self-sufficient, and they survived. In the words of Matthew Hertzog II in 1917: "We're not making the money the old folks used to make, but we're making a little, and we're still here."

Modernization came fitfully to Cane River. Phanor Prud'homme II bought the family's first car in 1910, while most people in the area still traveled by mule-drawn wagon. At Magnolia in the 1930s workers began driving tractors in the field—in many cases fields where their enslaved ancestors had labored. By the 1940s machines were doing more of the tasks long performed by mules and human workers, and many of the remaining workers left the plantations for employment in war industries.

The old plantation world was fading. At harvest time ranks of workers in the cotton fields of Magnolia and Oakland were replaced in the 1960s by mechanical pickers. Yet many of the old ways persisted. At Magnolia workers and planters still enjoyed baseball games and horse races. Oakland's store was the place to go for news and mail. The Creole tradition that had sustained planter and worker for nearly three centuries endured, and today remains an evolving, vibrant culture.

What Does it Mean to be Creole?

Creole In colonial Louisiana the term "Creole" was used to indicate New World products derived from Old World stock, and could apply to people, architecture, or livestock. Regarding people, Creole historically referred to those born in Louisiana during the French and Spanish periods, regardless of their ethnicity. Today, as in the past, Creole transcends racial boundaries. It connects people to their colonial roots, be they descendants of European settlers, enslaved Africans, or those of mixed heritage, which may include African, French, Spanish, and American Indian influences.

The Cotton Year

An Endless Cycle of Work

Life on the plantation revolved around the demand of the cotton crop. The labor cycle encompassed almost the entire year. In his 1858 book Fifty Years in Chains; or, the Life of an American Slave, Charles Ball, who had worked on both tobacco and cotton plantations, wrote: "The tasks [for tobacco] are not so excessive as in the cotton region, nor is the press of labour so incessant throughout the year." After tenant farmers and sharecroppers replaced enslaved workers, the labor cycle remained much the same. By the early 1900s, powered machines made some tasks easier, but picking was the last process to be mechanized.

The cotton year began in late March as workers plowed and planted the fields. After two or three weeks they used hoes to "chop" or thin the seedlings and remove weeds. They typically repeated this process four times over the summer.

In August, every available person was put to the task of picking the cotton. The overseer issued each picker a sack and a large basket. The grueling work lasted from first light until it was too dark to see. (A full moon could extend the labor well into the night.) Pickers repeatedly bent to pick low cotton, and often suffered deep cuts from the hard, sharp bolls. The overseer made sure the pace didn't slacken. The pickers emptied their sacks into their basket and carried them to the gin house for weighing. The overseer expected adults to pick at least 200 pounds a day.

The cotton had to be picked three or four times, as the bolls continually opened. Picking usually continued into the new year. In January and February, some workers pulled and burned the plants. Others mended fences and machinery and harvested cypress from the plantation's timberlands. In March, the cycle began again as workers readied the fields for plowing and planting.

Visiting the Area

Living Traditions on the Cane River

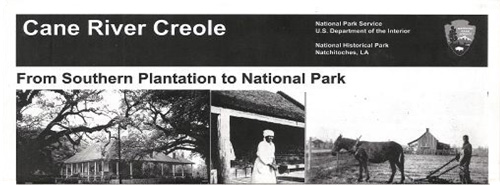

The historic landscapes and dozens of structures preserved at Oakland and Magnolia plantations tell human stories. They show us how the people who lived here and worked this land for over two centuries adapted to historical, economic, social, and agricultural change. Today their descendants carry on many of their traditions.

The Prud'homme and LeComte families built their homes atop the natural levees along the Cane River. They planted crops on the rich floodplain—much of it still in production—that slopes down to the cypress swamps.

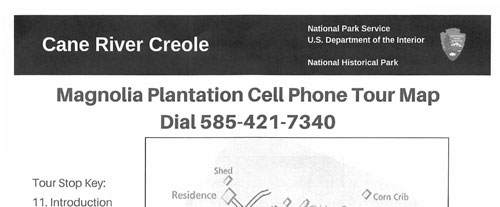

You'll arrive at Oakland "back of the big house," through the working part of the plantation. Sheds, shops, and storehouses recall the ceaseless tasks—from carpentry to the tending of livestock—that supported life on the plantations. The artifacts and fine interior details of Oakland's main house reflect the French colonial culture of the region.

At Magnolia you can see how the people who served King Cotton worked and lived. Visit the gin barn where they handled tons of fiber each day. Here they fed the steam-powered gin and operated the presses, powered first by mules and later by steam, to bale the cotton. At day's end they returned to their quarters (eight of their houses still stand here, in neat brick rows). The larger overseer's house is evidence of the plantation hierarchy.

Magnolia and Oakland are part of Cane River National Heritage Area. Homes, churches, military posts, and the land, which is still agricultural, support a broad understanding of the area's history and culture.

The heritage area include Magnolia's big house which is outside the park boundary. The original house burned during the Civil War. The Hertzog family rebuilt it in 1896.

(click for larger map) |

Visitor Information

Oakland and Magnolia are open daily except Thanksgiving, December 25,

and January 1. You may take self-guiding tours of both sites from 9 am

to 3:30 pm.

Accessibility

We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to

all. For information asm a ranger, call, or check our website.

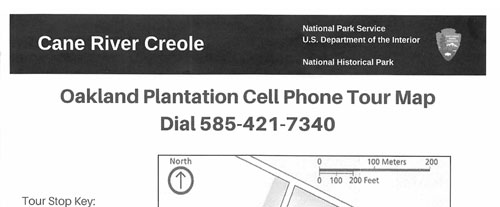

Oakland Plantation is 10 miles south of

Natchitoches, LA.

4386 Highway 494

Natchez, LA 71456

Magnolia Plantation is 10 miles south of

Oakland Plantation.

5549 Highway 119

Cloutiersville, LA 71416

Warning: GPS systems may not work accurately in rural areas. Call if you need directions.

Safety

Preservation and restoration of our historic structures are continuing

projects. This work and the plantations' uneven terrain can make touring

the park hazardous. Be aware of snakes, bees, and fire ants. Summer

temperatures can be extremely high. Wear walking shoes and bring water,

sunblock, and insect repellent. For firearms regulations check our

website.

Source: NPS Brochure (2018)

|

Establishment Cane River Creole National Historical Park — November 2, 1994 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Brochures ◆ Site Bulletins ◆ Trading Cards

Documents

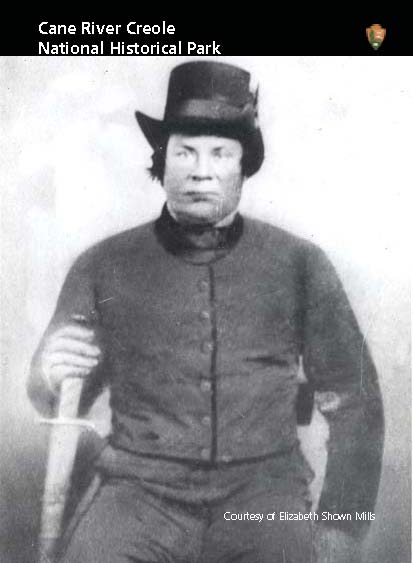

A Blacksmith's Son Goes to War: The Story of William Smith (2015)

A Brief Ethnography of Magnolia Plantation at the Cane River Creole NHP (Muriel Crespi, 2004)

A Comprehensive Subsurface Investigation at Magnolia Plantation (Bennie C. Keel, Christina E. Miller and Marc A. Tiemann, 1999)

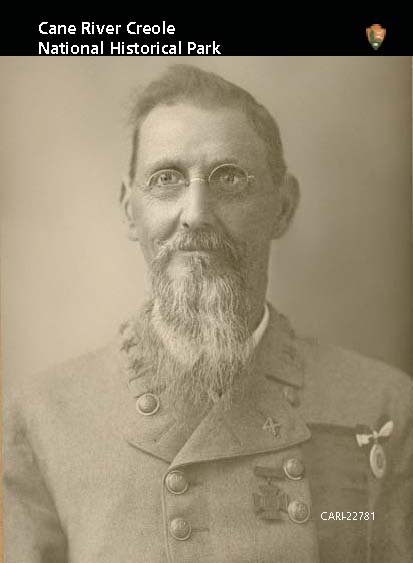

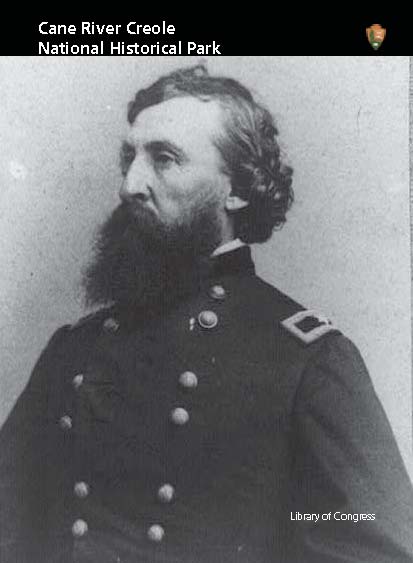

A Planter's Son Goes to War (2012)

Badin-Roque House Preservation Study (Sparks Engineering, Inc. and EnvironMental Design, July 26, 2018)

Cultural Landscape Report: Magnolia Plantation, Cane River Creole National Historical Park (Ian Firth and Suzanne Turner, December 2006)

Cultural Landscape Report, Phase 2: Oakland Plantation, Cane River Creole National Historical Park (Suzanne Turner Associates, LLC, April 2021)

Cultural Landcapes Inventory: Magnolia Plantation, Cane River Creole National Historical Park (2022)

Cultural Landcapes Inventory: Oakland Plantation, Cane River Creole National Historical Park (2022)

Enabling Legislation—Cane River National Historic Park/Cane River National Heritage Area (PL 103-449, 108 Stat. 4752, 103d Congress, November 2, 1994)

Final General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Cane River Creole National Historical Park, Louisiana (January 2001)

Foundation Document, Cane River Creole National Historical Park, Louisiana (September 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Cane River Creole National Historical Park, Louisiana (February 2017)

Frankly, Scarlett, We do give a Damn: The Making of a New National Park (Laura [Soullière] Gates, The George Wright Forum Vol. 19 No. 4, 2002)

Historic Resource Study: Cane River Creole National Historical Park (Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc. and Suzanne Turner Associates, June 2019)

Historic Structure Report: Magnolia Plantation, Blacksmith's Shop, Pigeonnier, and Carriage Shed, Cane River Creole National Historical Park, Natchitoches, Louisiana (HARTRMPF and Jack Pyburn, Architect, Inc., November 2003)

Historic Structure Report: Magnolia Plantation, Gin Barn (2004)

Historic Structure Report: Magnolia Plantation, Overseer's House (Hartrampf, Inc. and Office of Jack Pyburn, Architect, Inc., 2004)

Historic Structure Report: Oakland Plantation Big House (2004)

Historic Structure Report: Oakland Plantation, Gin Complex (Hartrampf, Inc. and Office of Jack Pyburn, Architect, Inc., 2004)

Historic Structure Report: Oakland Plantation, Prud'homme's Store (2004)

Historic Structure Report: Oakland Plantation, South Tenant Cabin (Hartrampf, Inc. and Office of Jack Pyburn, Architect, Inc., March 2004)

Historic Structure Report: Oakland Plantation, The Cottage (Hartrampf, Inc. and Office of Jack Pyburn, Architect, Inc., 2002)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Cane River Creole National Historical Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Newsletter (The Cotton Press): Spring 2013 • Fall 2013

Oakland Plantation: A Comprehensive Subsurface Investigation (Christina E. Miller and Susan E. Wood, 2000)

Oral History and Ethnographic Interviews with Traditionally Associated People of Cane River Creole National Historical Park (Dayna Bowker Lee and Rolonda Teal, December 2015)

Special Resource Study/Environmental Assessment, Cane River, Louisiana (June 1993)

"We Know Who We Are": An Ethnographic Overview of the Creole Traditions & Community of Isle Brevelle & Cane River, Louisiana (H.F. Gregory and Joseph Moran, December 1996)

Cane River Creole National Historical Park Video Tour 1 of 2

Cane River Creole National Historical Park Video Tour 2 of 2

Books

cari/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Aug-2024