|

CCC Forestry

|

|

Chapter X

WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT

|

THE creatures of field and forests, not domesticated by man are known as wildlife. Wildlife management is the art of producing and maintaining wild animal populations for recreational use. From the standpoint of the sportsman and recreationist, we are primarily interested in production and preservation of game animals, birds, and fish in coordination with other resources. |

What Is Wildlife? | |||||||||||||||||

|

Big game: Those dwellers of prairie or forest of large size such as moose, elk, bear, antelope, deer, mountain sheep, and goat. Small game: The smaller animals of forest and field including squirrel, rabbit, raccoon, and opossum. Fur bearers: Those animals of stream and lake such as beaver, muskrat, mink, and otter; and of forest and field such as fox, skunk, weasel, and marten which furnish much of the fur for women's apparel. Game birds: Birds of forest and field such as grouse, quail, pheasant, and wild turkey. Migratory Fowl: Wild geese and ducks are the principal species. Fish: Those fresh water fish, known as game fish, which furnish the maximum sport for anglers. |

| |||||||||||||||||

|

What is the relation of wildlife management to forestry, and what is the interest of the forester in relation to game management? Practically all the big game existent today lives in the forest. There they find adequate food and protection. Some game species, the squirrel for example, live only in the woods. Small game living in fields seek forests for protection, and obtain a great deal of their food from wooded areas. Game birds fly into wooded cover to escape pursuing hawks. When dog and gun would take their lives, they fly into the underbrush of nearby forests. Opossums and raccoons live in hollow trees; game fish live in forest-fed streams. WILDLIFE AND RECREATION The forests of today are designed to yield their greatest values to the greatest number of people. One of the greatest of these values is recreation, and here wildlife plays a major role. There is a close relationship between wildlife and forestry, between the forester and game management. WILDLIFE OF THE PAST Most persons are familiar with stories revealing the abundance of game in frontier days—about the hundreds of thousands of buffalo, elk, and antelope which grazed the prairies, and the abundance of forest game which furnished food, clothing, and sport for decades. Wholesale destruction of the prairie game animals reduced their numbers to small herds which were driven by civilization to the rougher, mountainous, forested areas. Small game in some regions has increased since the coming of the white man. In some agricultural sections cottontail rabbit and quail populations have greatly increased. WILDLIFE OF TODAY In the United States today the countless numbers of wildlife have been greatly reduced. The buffalo no longer exists as a game animal. A few remain in national preserves, parks, and zoos. Elk are found in the more isolated parts of the mountain regions, where they are protected on national park and forest lands. Deer, like the elk, live principally in the secluded portions of the West; a few remain in the North Central States, small herds exist in New York and New England, in the Carolinas, and in Florida. In Pennsylvania lumbering operations, which greatly increased the available food for deer, linked with a good game-protection organization, has built up an optimum deer population (the greatest number that can thrive in an area) from the few that remained 25 years ago. Bear are found in only a few States, and their numbers are rapidly declining in some of these. In many sections of the United States small game is very scarce. Although some species are increasing in a few sections and some areas occasionally become overstocked, there is a general decline in game population as a whole. Some species are almost extinct. The native pheasant and sage hen are seldom found, and migratory waterfowl, like other game birds, are on the decline. The wild goose is becoming scarce, and the various species of ducks are declining in numbers. Fish populations, like animals and birds, have also decreased. There is urgent need for more information on wildlife. Surveys to determine numbers and available feed are necessary for good game management. Estimates for national forest areas show big game population, 1934, as follows:

|

Wholesale Destruction. Big Game Is Driven Out.

Scarcity of Game. Little Information Available on Wildlife.

| |||||||||||||||||

|

PROBLEMS OF GAME MANAGEMENT Game-management problems are often baffling, even to the expert. Some of the principal problems are listed here: (1) Prevention of extermination of species: Few species of game have been lost in the United States. The bison (buffalo) was saved at the last moment, but the passenger pigeon and a few others have vanished. Game management should protect all species and prevent any further extermination. (2) Space for game: Home and farm lands now occupy areas formerly inhabited by game. The problem of finding and reserving space for homes for wildlife, especially those species requiring large areas of wilderness, is a major one. (3) Feed for wildlife: Protection of game often results in animals multiplying until there is not enough food to maintain the population. Feed must be furnished in some form. Winter feeding is sometimes necessary. Forest fires destroy all types of feed for wildlife, and after fires ravage wildlife homes the feed problem may become acute. (4) The problem of overpopulation: Game has a tendency to collect in areas, and, rather than wander great distances in search of feed, deer and elk will starve in the crowded areas. Where overpopulation occurs, good forage plants are destroyed by overgrazing and trees are sometimes stripped of browse. Animals in overcrowded areas, weakened by hunger, are easily infected with diseases and many die.

(5) Protection for game: Nature has provided some protection for wildlife against man and their natural enemies. For example, the rabbit is a swift runner, the slow turtle has a protecting shell, the porcupine has spines, the skunk has odor, and the squirrel is a swift climber. Adults of large species have horns, antlers, or long teeth. The newborn animals have no scent until they are a few days old, and predators, not being able to smell them, cannot find them where they have been hidden in vegetation by the mother. Protective coloration also prevents animals being easily seen. Some species of the North, such as snowshoe rabbit and weasel are brown in summer and white in winter; their color blends with the earth and leaves in summer seasons and with snow in winter. Such protection serves animals well against their natural enemies, but Nature did not consider the fire arms, traps, fences, and dogs of man. The game manager must aid in protecting wildlife against over-attack by predators and man. |

| |||||||||||||||||

|

VALUES OF WILDLIFE Some of the values of wildlife were shown in Chapter II. It is impossible to show true dollar and cents values for game because it is so related to almost every forest land use; but it has definite economic, social, and scientific values. Of course, there is a negative value also. For example, forage eaten by big game might well support domestic stock. But the positive values seem to surpass the negative. The United States Biological Survey estimates the annual economic value of wildlife in the United States as follows:

Social values of wildlife cannot be estimated in dollars and cents. The values of recreation, especially forest recreation, were pointed out in Chapter II. Game is attractive to the huntsman, fisherman, nature lover, and photographer. Wildlife attracts us to zoos or to the circus and likewise to forest areas. There is beauty about wildlife in its forest home which appeals to us. Artists paint pictures of it and designers of beautiful things weave in the beauty of wild beasts and birds. Something stirs us deeply when we see a graceful, antlered buck standing alert among green trees, or a V-line of south-winging wild geese. Besides its economic, social, and esthetic values, game has a scientific value best explained by zoologists and the medical profession. Studies of animals, birds, and fish have made possible invaluable contributions to the Science of Zoology and have benefitted human existence.

It has been said that everyone should have some sort of hobby. The health and the recreational value of an outdoors hobby can hardly be questioned. An interest that takes one out of doors and away from cares does much to make for better health and more interesting living. A hobby which interests one in the production and management of wildlife has a twofold value—first, to the individual practicing it and second, to society, in helping to build up the quantity of wildlife. |

Social Values.

| |||||||||||||||||

|

MANAGEMENT OF SMALL GAME The management of small-game species extends to every part of the country. Prairie and mountain, forest and field, all have some kind of game. The problem of small game protection is largely one of education. Sportsmen's and businessmen's clubs can do much to improve game conditions. Boy scouts, girl scouts, 4—H clubs, and the Future Farmers of America are mediums for proper dissemination of game-management information. Game has definite value to the landowner just as crops of fruit and grain. His interest in the protection of the game on his farm is a natural one as is his interest in protecting his livestock and crops. Such an interest is very helpful in restoring and protecting game population, since the existence of game in this country is largely up to the attitude and activities of the farmer. He can, though his efforts, do much to maintain an optimum small-game population throughout the country. COVER Game needs a place to live. It must have protection from predators (animals or birds which kill game for food), from dog and gun, and from severe weather. One of the best forms of protective cover for farm game is the farm woodland. There rabbit, squirrel, quail, pheasant, and other species may live. Squirrels stick closely to woods. Quail work in and out of timber, using woods and underbrush as emergency protection when molested. Hollow trees furnish living quarters or storehouses for squirrels. Brush left on the ground makes excellent cover and protection from owls, hawks, and other predators. Thickets growing on rough corners of the farm, creek banks, and rocky land make suitable breeding places and good habitat for small game. Landowners may provide game cover by leaving hollow trees for homes, and brush and thickets for protection. FEED Regardless of the amount of cover for upland game, it cannot exist without sufficient food. The farmer may help to furnish food for game and birds during winter seasons by leaving uncut patches or corners of food crops such as corn, wheat, sorghums, kafircorn, millet, sunflowers, soybeans, and field peas. This is often added to by permitting weed seeds to ripen before mowing, or allowing weed fields to stand through the winter. Seed trees left in woodland or scattered on the farm furnish additional feed for small game.

Emergency feeding of some game species is successful and may be necessary in unusually hard winters when it is extremely cold and snow is deep. Suitable inexpensive feeding bins can be built which require little attention. These should be placed in secluded places frequented by game, but near enough to be under periodic observation. It is, preferable, however to give nature the opportunity to provide for the denizens of field and forest since artificial feeding tends to make beggars of them and they lose their game qualities. STOCKING If desired species are not present on lands to be put under management, they may often be obtained from the game organization of the State or from sportsmen's clubs. Sometimes game for introduction may be had free. The farmer-game manager has opportunity to raise, release, and protect certain species on his farm. Native species are usually most successfully introduced, and new species should not be released in large quantities in any locality until they have proved to be both desirable and suitable to the habitat. Introduced game species must be given complete protection and the necessary environment factors must be provided for them. LAWS If game laws allow hunters to take their limits in the home State and then go into the neighboring State at the opening of its hunting season and take the limit there, each State is supporting a double population of hunters. A national organization seems necessary to bring about united effort in restoring wildlife populations, creating better game laws, and providing law enforcement. The management principles relating to small game apply alike to animals and game birds. Fur-bearers require similar conditions, except that they prefer and are most abundant in streamside and swamp land. In addition to protecting, feeding, and helping to secure and enforce proper game legislation, the farmer-game manager can assist in game conservation by: 1. Posting his land against open hunting. 2. Regulating the kill of his game. 3. Killing stray cats. 4. Controlling natural enemies of game. 5. Tying up his dogs during game breeding seasons. 6. Preventing destructive fires. 7. Organizing with his neighbors, a game protective association. The sportsman can insure more game and better hunting by: 1. Cooperating with the farmer in his efforts to better game conditions. 2. Being more considerate of the wishes of landowners. 3. Being careful of the farmer's property, especially livestock. 4. Being governed by existing game laws and helping to improve and enforce laws where necessary. |

Emergency Feeding is Sometimes Necessary.

How the Game Farmer Can Help.

How the Sportsman Can Help. | |||||||||||||||||

|

In the denser populated regions the management of big game is a greater problem than small game management. Game of the larger species was named earlier in the chapter. Wolves, coyotes, foxes, wildcats, and mountain lions are game of the predaceous type, commonly called predators. HOMES The lack of space and conditions for homes for big game limits their numbers. The national forests and parks therefore provide most of the homes for the larger species. In the Rockies and the Far West, the extensive forest areas under National, State, and private ownership are well adapted to the raising of big game. In the East and South, forest areas are broken and more thickly settled, furnishing poor habitat. The purchasing of more land by the Federal Government will help to solve the problem of living space.

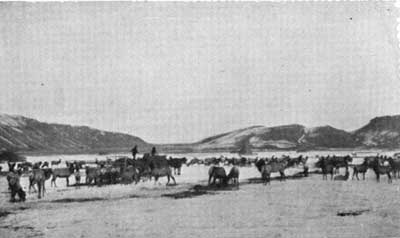

THE YELLOWSTONE HERDS Excellent examples of the problems involved in managing big game and of the methods of solving these problems are to be found in the Yellowstone Park and the adjacent national forests, where America's big game abounds. The elk have offered an especially difficult problem. In summer, forage is abundant in the park and adjacent areas, but since the altitude ranges from 6,000 to 10,000 feet, deep snows in winter prevent elk from feeding. They must seek the lower altitudes north and south of the Yellowstone area. There, forage is becoming so scarce that the animals are unable to find sufficient feed. Much of the tree browse has already been consumed. Cold winters with deep snows prevent elk from pawing away the snow and finding forage. Even though the elk are able to reach ground they may find no feed, because heavy grazing of any area by either game or domestic stock during the summer leaves no reserve for severe winter weather. In the winter of 1919, it was estimated that 8,000 head of elk of the north Yellowstone herd starved to death. Park and forest rangers have for years fed the elk hay during hard winters. This prevented starvation but brought about partial domestication of the elk, which is undesirable. Conditions are similar on the south side of the Park. The elk winter in Jackson Hole where they have been so limited in range that little forage is left. The section is overpopulated in winter and many starve. The Government has fed this herd, and the animals have become practically domesticated beggars. They make no attempt to forage for themselves, which adds to the management job. Hay is scarce and hard to produce, and contains species of plants harmful to animals. Poisonous weeds and such plants as foxtail grass, having spines which irritate the mouth and digestive organs, often cause death. Crowded together as they are in the Jackson Hole herd, the animals are easily infected with diseases. Animals weakened by hunger are more susceptible to disease than stronger ones. The common diseases of the elk of the Yellowstone region may be caused by (1) parasites, (2) bacteria, (3) physical deficiency, or (4) mechanical injury. The parasites causing serious infections are ticks, deer hot fly, tapeworm, and lungworm. The greatest of these is probably the lungworm, which causes infections and congestion of lungs, often resulting in death. The most threatening bacterial disease is a disease of the mouth and head which attacks tissues, bones, and eyes. The bacteria begin their work in the mouth, entering the wounds caused by barbs on foxtail grass which grows profusely in the area. Thousands of these tiny spears work their way into tissues of the mouth causing infections and decomposition. The bones of the head are infected and become soft or decomposed. When the barbs or bacteria reach the eyes blindness results. This disease has the common name of "sore mouth," but is scientifically known as necrotic stomatitis. Bang's disease, which is an infection of organs of pregnant animals which causes them to drop their young before maturity, is also caused by bacteria. Deficiency diseases are caused by improper and insufficient feed. Lack of sufficient mineral elements causes softening of bones. A weakened and undernourished animal contracts other diseases easily and has no vitality to combat them. Wounds from gunshot, broken bones, and lacerations, if not fatal in themselves, may cause diseases of bone and joints. The disease-prevention problem is most easily solved by providing ample forage. Good forage and browse prevent most of the diseases mentioned. Prevention of overpopulation and crowding checks the spread of bacterial diseases. Salting on ranges may provide some of the necessary mineral elements which are deficient. Either rock salt, molded blocks, or loose salt may be used. Much of the granulated salt is lost by weathering. Coarse, lump, or block salt is better. Salt should be placed in salt logs, boxes, or natural depressions in rocks. Containers may be made by chopping cups or troughs in logs, or they may be made from heavy lumber. The situation encountered in managing the elk herds of the Yellowstone suggests the difficulties met with in managing big game elsewhere. On some areas, such as the Kaibab Forest in Arizona, deer offer an equally difficult management problem.

SOLVING BIG-GAME PROBLEMS By a careful range and game survey the needs of game and the amount of feed available for them may be determined. The reduction of livestock and game on overgrazed ranges and artificial reseeding on some areas will do much to increase the quantity of feed and otherwise improve such areas. It seems desirable in such cases as the Yellowstone elk herd to prohibit domestic livestock grazing. However, under present conditions on much of the western range lands, a sane adjustment between livestock and game range will allow for ample numbers of both classes, if properly managed. State and Federal authorities have cooperated in improving the conditions encountered by the Yellowstone herds. Areas near the park have been closed to livestock grazing. Purchase areas which will provide adequate winter range have been recommended for the southern herd. Properly managed, such areas should help to solve the game-management problem. Timber management can do much to increase feed for game. Young trees and lower branches of mature trees often furnish the major part of winter feed for browsing animals. In crowded areas, especially in hardwood stands, all the lower branches of trees as high as the animals can reach are often consumed. Timber management of hardwood stands can, by encouraging smaller timber sales and breaking up large areas of even-aged stands, produce more food for browsing and other game animals. Timber-stand-improvement work which opens up the stand, stimulates sprout growth, and allows other vegetation to come in, also increases game feed. On areas in hardwood forests (refuges, etc.) where tree browse is getting out of reach and which must support certain numbers of game, the removal of the more worth less species gives nature a chance to produce more food. Abandoned farmsteads which do not support tree growth can be improved by planting game food and cover species, provided the game population on adjacent areas is not so high as to make planting impossible. Deer in Pennsylvania, for instance, eat the seedlings almost as fast as they are planted. Preserves and breeding grounds are necessary to protect game populations which are on the decline, and provide a good means of restocking depleted areas. State and Federal agencies have established many protected areas, but there are still many sections where preserves could rebuild game populations. However, after animals have become established on protected areas, overpopulation often occurs, which results in feed shortage. Such overpopulation can be prevented by live-trapping the animals and shipping to unpopulated areas. Areas similar to the Kaibab Forest in Arizona, where a crisis existed and immediate reduction of large numbers was necessary, may be opened to controlled hunting. After the required number of animals has been taken, the area may be closed again. |

Park Service Provides Space. Big Game Seek Secluded Areas.

Winter Conditions Bad.

Diseases. Causes of Diseases.

Deficiency Diseases.

Regulating Game Population.

Regulating Game Population.

| |||||||||||||||||

|

The management of carnivorous (meat eating) game requires a different type of control. The larger predators are wolves, coyotes, and mountain lions. Hunting and trapping of these predators by State and Federal authorities has greatly reduced their numbers. The smaller predators are likewise controlled but are not being exterminated. Many States now classify hear as a game animal. If food is scarce bears often rob beehives and kill domestic stock, but bears as a group are considered desirable game animals. |

| |||||||||||||||||

|

MANAGING MIGRATORY FOWL The management of migratory fowl ranks with management of other game in importance. Wild geese are becoming very scarce, and the duck population is definitely decreasing. Some migratory species of pigeons have completely disappeared and doves and woodcock are becoming scarce. Marsh and waterfowl are the principal species of game birds that migrate. Of these, ducks and geese are most important. Both these species are good breeders, and if unmolested, multiply rapidly on marshland waters. Wild geese breed and summer in the Northern States or in Canada. In winter, these same fowls are found in the marshes of the Southern States. Ducks breed and rear their young in the northern or temperate regions. They migrate for shorter distances than do geese and some species spend the entire year in the same locality. PRESERVES AND BREEDING GROUNDS Preserves and breeding grounds provide retreats for waterfowl where they are not molested. Additional food plants may be introduced in preserves such as wild rice, eel grass, marsh grass, pond weed, and wild millet. In many areas wild rice is the best marsh food for ducks and geese. SANCTUARIES AND REFUGES Inland sanctuaries and feeding grounds furnish places where birds in migration can rest and feed. In sections where a great deal of shooting is done refuges give birds a chance to flee from hunters when driven from their customary haunts. Sanctuaries may prevent the extermination of the entire flock, thus providing breeders for the next season.

LAWS The enforcement of recent Federal and State shooting laws gives additional protection to waterfowl. In some sections laws are inadequate and enforcement so poor that proper management is difficult to practice. In such cases better laws and enforcement would greatly improve water fowl conditions. |

| |||||||||||||||||

|

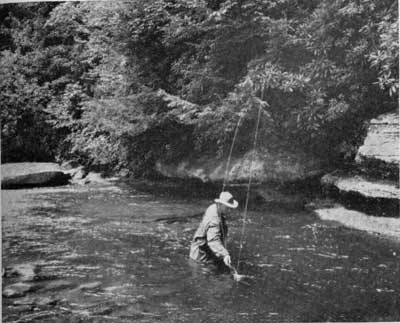

FISH MANAGEMENT Fish management is also closely related to forestry and to management of other wildlife. Streams in forests are good game-fish streams because protection from the direct rays of the sun makes them cooler. Various species of trout and other game fish are especially adapted to forest streams. Trees and other forest vegetation are conducive to fish-food production. Fresh-water fishing claims the greater number of amateur anglers. State organizations in cooperation with Federal agencies have done and are doing much to improve stream conditions for fish production. Private agencies and individuals can also help in fish management. PROTECTING FISH STREAMS Constancy of stream flow is particularly advantageous to fish culture. Rivers having extreme flood and low-water stages present conditions adverse to fish life. Floods sweep away fish food, destroy protected homes of fishes, and wash away or cover eggs and nests. Eggs and fry (very small fish) may be destroyed by heavy silt carried in flood water. Pollution of fish streams by chemicals from industrial plants often kills fish and makes the streams unfit for fish to live in. Prevention of such pollution is necessary if fish are to live in the stream. The burning of watersheds is harmful to fish. As shown on page 64, forest fires destroy fish food and stream shelters, such as trees and logs, which furnish shade and food. Protection of watersheds from erosion is favorable to fish protection. Slopes covered with vegetation control water run-off and do not easily erode, thus maintaining clearer, more constant streams.

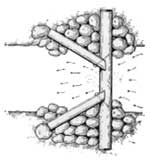

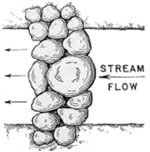

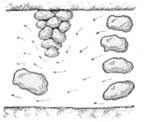

IMPROVING STREAMS AND PONDS Streams and ponds may be improved to make better homes for fish. In the first place, fish need protected places where they can escape from larger fish. Small and large fish alike must have protection from swift water and debris during flood periods. Additional protection can be artificially established by building dams which retard swift water and make hiding places for fish. Current deflectors also slow up swift water and make undercuts in banks. Where stream bottoms are settled with silt, devices can be built to speed up the current which cleans the gravel, thereby providing spawning grounds and food-producing areas. Fish ladders installed in dams allow fish to travel upstream for breeding. In slow-running streams changes can be made which will speed up the current, thereby decreasing stream temperature and at the same time providing pools for shelter, and riffle areas for feeding grounds. The creation of better stream conditions brings about an increase of fish foods. Experiments in the planting of aquatic fish foods are being carried on, which may prove successful. Poor types of fish, unfit for food, should be seined from waters where game fish are being managed, to prevent losses of young game fish and fish eggs. PLANTING AND RESTOCKING Fish planting or restocking in suitable streams is one of the important jobs in fish management. Streams formerly unstocked often make excellent rearing streams when fish are planted. Where considerable fishing is done, it often becomes necessary to restock with young fish every year to furnish an adequate supply of game fish for the hook. In some cases even legal-sized fish are planted in streams for breeders or to furnish fish for anglers. Fish for stocking are produced in hatcheries which are managed by various Federal and State agencies, and the fry (very small fish), when matured enough to take care of themselves (fingerlings), are transported and released in streams. Many millions of baby fish are planted in forest streams of the United States annually. LAWS Just as animal wildlife must be protected by adequate laws and proper enforcement, so must fish be protected. Catching small fish at any time, and mature fish during spawning season, reduces the available supply and results in poor fishing. If fishermen would be governed by the laws, this practice would be greatly diminished. A sportsman's code. 1. Obey the game laws of county, State, and Nation.2. Be extremely careful of all firearms. 3. Look before you shoot—it may be another hunter. 4. Wear red when hunting. 5. Don't be a game hog—a true sportsman doesn't kill wantonly or maliciously. 6. Be careful with fire—fire kills game and destroys their homes. 7. Leave plenty of game for breeders. 8. Respect the rights and property of others. 9. Love nature and the denizens of forest, field, and stream. |

Why Do Floods Destroy Fish? Effect of Forest Fires on Fish.

| |||||||||||||||||

|

SUMMARY Wildlife management is the art of producing crops of wild animals, fish, and birds for recreational purposes. Game may be classified as follows: Big game, small game, furbearers, game birds, migratory fowl, and fish. Management of wildlife is closely related to forestry. Small game can exist in nearly all sections of the country. Its management, therefore, is more important to a greater number of people than management of big game. The management of small game relates also to game birds and to fur-bearers. The problems of small-game management are to provide cover and habitat, feed, stocking and restocking, and legal protection. Big game, although fewer in numbers than small game, involves more complicated management problems. Big game requires adequate space of forest or wilderness area, proper and sufficient feed, and protection from man, predators, and disease. Prevention of overpopulation, transportation, and restocking are also problems of big-game management.

The management of carnivorous animals should control them rather than exterminate them. Predators often prey upon other game or on domestic stock or fowls, and populations must necessarily be kept low. In managing migratory fowls, principally wild geese and ducks, the main problems are providing preserves and breeding grounds, sanctuaries and refuges, and introducing feed plants. Fish management has to do with rearing and stocking streams, improving streams for fish homes, and protecting fish. Afforesting and preserving forests on watersheds and prevention of forest fire helps to maintain better fish streams. THE OUTLOOK It has been estimated that from 1920 to 1930 the number of hunters and fishermen increased 400 percent in the United States.1 A study of 14 Southern States showed that there were practically as many hunters and fishermen as participants in all other major sports.2 Americans by nature and environment are sportsmen. Will there be wildlife in the future to supply the recreational needs of these sportsmen?

Many State and Federal agencies, foresters, conservationists, naturalists, and sportsmen are interested in game management that will provide for production of wildlife in sustained crops for this recreational use. Emergency Conservation Work performed by the CCC has materially improved wildlife conditions. Erosion control, forest and stream improvement, and fire protection have helped the cause of wildlife reproduction. Under an ideal situation ample game would be distributed over all available areas, instead of being heavily concentrated in fewer areas. With adequate food and protection, and with regulated kill based upon optimum population, sufficient quantities of wildlife should be made available for all forms of recreation in America. |

Big Game Management.

Homes for Waterfowl.

|

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

ccc-forestry/chap10.htm Last Updated: 02-Apr-2009 |