|

CCC Forestry

|

|

Chapter XI

RANGE MANAGEMENT

|

INTRODUCTION THE term "range" is generally associated with stock raising in the Western States. While it is true that most of the unimproved grazing land in the United States lies in the West there are vast areas in the Eastern States which are grazed. In the South, it is estimated that 149 million acres of forest lands are grazed by domestic stock. In the Central and Northeastern States, of 63,000,000 acres of forest lands, principally farm woodlands, over half are grazed.

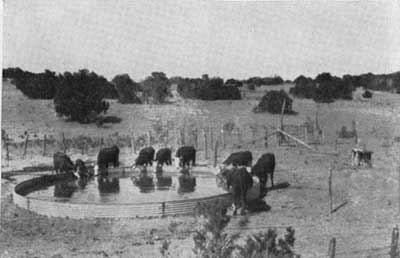

Most of the forest lands contain forage suitable for grazing either in natural openings, prairies or parks in the timber, or as undergrowth beneath the trees themselves. This forage furnishes a valuable crop which, with proper management, may be used year after year in addition to the timber which is grown on these lands. Aside from the forests, there are vast areas of prairies, deserts, brushlands, and other unimproved lands which are used primarily for grazing purposes. All classes of domestic stock graze to some extent. The particular class—cattle, horses, sheep, goats, or hogs is determined by the type of range land, character of forage, available water, and other factors. The same plants do not grow under all conditions. On the desert, there are usually many coarse shrubs and other plants which normally grow in an open stand. In dense timber, there often is little or no forage on the ground, while an open stand of trees usually contains a considerable amount of undergrowth in the form of shrubs, weeds, and grasses. The Forest Service has classified ranges into 10 types: 1. Grassland. The type of range and its condition affect the animals which are grazed on it, as well as the profits to be made from such grazing. If the range is overgrazed, eventually it will support only smaller numbers of stock. Lamb and calf crops ordinarily are smaller on ranges which have been too heavily grazed. If the better forage plants are gone, stock will eat more poisonous plants and losses will become greater. The stock from some of the better ranges is shipped to market as "grass-fat" or "range-fat" and commands a better price than stock from the poorer ranges, which is shipped as "feeders." Finally, if a range is grazed hard enough and long enough, the vegetation may become so sparse that wind or rains start erosion, carrying away the soil itself so that most of the value of the range is lost for many years to come. The larger portion of the grazing lands in the United States is in private ownership. These pastures are grazed by the stock of the owners or they may be leased to other stockmen. However, there are millions of acres of national forest range, lands of the public domain, and Indian reservations, as well as lands owned by the various States. Grazing on these public lands is vitally important to the livestock industry. The surrounding farms and ranches produce hay and other crops which are fed to livestock during the winter. Many of the western ranches are located in high mountain valleys where hay is the only crop which can be grown or so far from railroads or markets that crops cannot be shipped but must be fed to livestock and marketed "on the hoof." Summer grazing is cheaper than feeding, and stock thrive better on open forage than on dry feed. Thus, public ranges provide means for maintaining farms and homes which could not otherwise exist. |

"Range-fat" Animals Bring High Prices. Most Forage Lands Privately Owned.

Public Ranges Help Maintain Farms and Homes. | |

|

HISTORY OF THE RANGE The history of grazing in the United States, especially in the West, records many struggles between stockmen. The public domain (unreserved, unappropriated Federal lands) was once open to grazing without regulation. Cattlemen could graze their stock on free range without restriction. Small herds grew into large ones, and more and more stockmen put herds on the range. Large companies were organized in the East and in Europe, hoping to "clean up" in the cattle business. Good range became scarce. Scarcity of water was another problem. Conflicts arose, which grew into private wars, and the power of the six-shooter was often the law. The country was unfenced, and the cowboy rode the range, preventing straying to a certain extent and rounding up the stock for branding or shipping. For a time tremendous movements of livestock took place, as when Texas cattle were taken to northern grass in Wyoming, Montana, and other States over the famous cattle trails. Sheep were introduced, and the bands soon increased by the thousands. Because sheep were closely herded they could be held on any part of the range until the forage was entirely consumed. Clashes between sheepmen and cattlemen developed over "free range" and water rights, and some bloody battles resulted. Such a state of affairs demanded and led to an orderly settlement of the problems and eventually resulted in the beginnings of range management. On the national forests, separate ranges were laid out for sheep and cattle, and individual herds were allotted definite areas. Forest officers, among their duties, assumed the supervision of range use. Gradually numbers of stock and seasons were fixed and certain methods of handling the animals were required of the owners. Fees were collected and permits issued. As other lands came into the ownership of States, they were leased to individuals, companies, or associations. Ordinarily, the management of these areas is left to the judgment of the stockmen, and numbers and seasons are not specified. Finally, through the Taylor Act, provision was made for the orderly use of the public domain. There is need for more information regarding proper methods of handling stock and lands, and this problem has been taken up by various State and Federal agricultural experiment stations. Much of the knowledge concerning proper range management has been made available by these experiment stations and is obtainable in books and bulletins. |

Driving the "Dogies."

| |

|

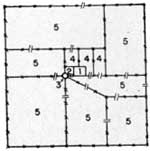

Range Management may be stated briefly as the best use of forage resources, through practice of the following principles: 1. Restoring and maintaining satisfactory growth of good forage plants. 2. Use by the proper class of stocks. 3. Seasonal use. 4. Regulation of number of stock grazed. 5. Proper distribution of stock. 6. Improvement of the range. 7. Specialized handling to meet local conditions. 8. The correct balance between grazing and other uses such as watershed protection, timber growing, recreation, and wildlife. RESTORING AND MAINTAINING FORAGE Where the better grasses and forage plants have been weakened or killed out through poor grazing practices, the range cannot furnish good feed. Consequently, it becomes necessary to manage the range in such a manner that the valuable plants can reestablish themselves. In order to obtain an idea of the quality and quantity of forage, it is well to estimate the density or the amount of ground covered by the plants on the range. Ranges in which plants are small and sparse and in which there are many areas of bare ground may be compared with ranges which have been properly grazed or with nearby areas where grazing has not taken place, as in fence corners, along railroad rights-of-way and similar protected plots of ground. If the forage stand becomes thin, it is an indication that some changes in the system of managing the range must be made to allow the better plants to come back. Livestock will eat certain plants and leave others. If a range is closely or improperly grazed, the better plants which stock prefer will eventually be weakened or killed out, leaving the less valuable plants more space in which to grow and spread over the range. Under such conditions the ground may be covered with plants, but they are not the plants which livestock prefer to eat. Stock which is forced to graze them does not thrive. This composition of forage, or the relative amount of good and poor forage plants on a range, may be compared with properly grazed range or with protected plots, in the same way as density is compared. PREVENTING FIRE Fire destroys not only growing plants, but also seeds and humus. Forest fire can kill all herbage and undercover, and in dry seasons grass fires can likewise consume forage on open land. Limited grazing helps to prevent fire. Plants which would grow up and die, thus causing fire hazards in the fall, are grazed down during the summer. Safety practices to prevent fires will do much to prevent depletion of forage and consequent erosion. PROPER CLASS OF STOCK Cattle prefer grass, but on browse ranges they will eat shrubby plants. They do not, however, care for most weeds. They prefer flat or rolling range with plenty of water and shade. Steep or rocky hillsides are usually not grazed if feed is available along creeks or in meadows.

Sheep, on the other hand, prefer weeds in spring and summer, grass in the fall, and on the winter ranges eat brushy plants or browse, such as sage and shadscale. Although sheep prefer water daily, they can go for extended periods without drinking. Even in the summer, if the forage is good and there is plenty of shade on the range, they may not drink for several days or weeks. During this time their moisture requirements are supplied by the herbage and by the dew on plants which they consume in grazing. Sheep do better on rough, mountainous range than cattle and make better use of the forage in dense timber. Horses prefer open, grassy ridges. They travel long distances from water and make use of many semidesert areas. They prefer grasses to most weeds. Goats are frequently grazed to good advantage on rough and rocky range, as in the Southwest. They prefer browse or shrubs to other classes of forage. Where they are held too long on one range they frequently damage young trees by eating the twigs and branches and by gnawing bark. Hogs make use of ordinary forage only to a limited extent. However, in the East, South, and Southwest where beech or oak is found, hogs are turned into the forest or brush ranges to fatten on the mast (acorns, nuts, and seeds). These habits and preferences of grazing animals must be considered if a range is to be utilized properly. Grazing cattle on a rugged area usually results in overgrazing of creek bottoms. Sheep, on the other hand, often make little use of forage in wet, marshy meadows where cattle can be grazed to good advantage. Certain poisonous plants may determine which class of stock should be grazed. Sheep may be grazed on ranges where tall larkspur, which is particularly poisonous to cattle, is found. Economic factors frequently determine the class of stock to be placed on a range. In many sections of the West, sheep are held on low spring ranges until after shearing and lambing is completed, and about July 1 are placed on the high mountain meadows, which are then ready to be used as summer range. Cattle, which are often held in fields in the spring, must be moved to summer range earlier, to permit the raising of crops. Consequently, cattle summer ranges are quite often found in the foothills and low mountains, while sheep go to the higher country. SEASONAL USE It has been found that if ranges are grazed as soon as plant growth begins in the spring the forage is weakened and the carrying capacity of the range is reduced. Range investigators, therefore, recommend that stock be held off the range until plants have made sufficient growth. Certain early grasses, such as bluegrass, should have flower stalks. The average grasses should be at least 6 inches in height. The date when grazing may safely begin naturally varies according to altitudes. Vegetation develops later on north slopes than on south slopes. Livestock, especially cattle, have a tendency to graze the higher ranges as soon as the snow melts and often before the forage has made sufficient growth. This can be prevented by "riding" or by fencing and confining the stock to the lower areas, reserving the higher ranges for summer use. On most high sheep ranges there is an abundance of weeds early in the summer. Later these weeds dry up or are killed by early frosts and sheep must eat grass. On such ranges, management plans often include grazing the band twice over the same area—the first time fairly rapidly, to make use of the weeds, and the second time to secure the grass forage. Certain plants, such as lupines (poisonous) should not be grazed by sheep until they are rendered less harmful by frost. If plants are closely grazed they cannot produce good seed crops, and eventually those good plants which reproduce through seed only, disappear from the range. This fact must be taken into consideration in connection with spring grazing. By keeping animals off the ranges, through fencing or riding, until seed have developed, natural seeding is provided and the quality and quantity of forage is assured. Under another system the range is divided into several units or pastures. Stock are grazed early in a certain pasture for one or more seasons, the forage in the other pastures being permitted to grow and develop seed. Then the order is changed. One of the other areas is used early for a season or two and the originally grazed area is allowed to rest and develop seed during the spring months. This is known as deferred or rotation grazing. REGULATION OF NUMBER OF STOCK Much damage is done through overstocking (crowding more animals onto a range than it can support). Some stockmen believe that by placing greater numbers of stock on a range, the cost of production per pound of beef or mutton is decreased. Experiments have shown that this is not true. More money is made from animals in a conservatively stocked pasture than from those on an overstocked range. Stock take on additional weight on a moderately grazed range; better calves, lambs, and wool crops are secured; losses are smaller; and there is less need for supplemental feed, such as hay. These gains more than offset the higher pasture cost of grazing fewer stock. Overgrazing may be recognized by several signs. As is the case when too early grazing is practiced, many of the better species of good range plants disappear and poor or harmful species take their place. Where overgrazing has not progressed very far, this change may consist in the gradual increase of the poorer or poisonous plants. Later, under continued destructive grazing, the range plants may consist almost entirely of weeds or shrubs, which are of no value to livestock. Overgrazing may result also in damage to tree reproduction. While this is especially true on sheep and goat ranges, a certain amount of damage will occur also on cattle ranges. The better shrubs are usually closely grazed and where overgrazing is severe, only dead shoots remain. Finally erosion sets in and barren spots appear where the fertile topsoil has been carried away by wind or water. Gullies begin to appear on the hillsides and deeply worn stock trails are seen where the plant cover has been thinned out. A good stand of grasses and other plants holds back the water after heavy rains and aids the absorption of this water by the soil. It also prevents the carrying away of the soil. When these plants are destroyed, erosion sets in rapidly. A good rule advocated by the United States Forest Service is to leave from 15 percent to 25 percent of the better forage on the ground when stock are taken off the range. This assures sufficient cover to prevent erosion, permits seeds to ripen, and prevents extermination of good forage species.

PROPER DISTRIBUTION OF STOCK On many large ranges some areas are closely grazed or overgrazed and others are not grazed as heavily as they should be. On cattle ranges, creek bottoms and meadows are frequently over grazed while the steeper hills are very lightly used. Ranges which are at some distance from water often are ungrazed. When grazing sheep are brought back to a central bed ground night after night, the forage around the bed ground is gradually destroyed while range at a distance is left untouched or lightly grazed. Such a condition not on]y tends to waste a part of the forage but ultimately leads to the destruction of the most desirable range areas. This is especially true if the range is heavily stocked, since the more accessible and desirable portions carry an increased number of animals and destruction is rapid. On cattle ranges better distribution can be secured through various improvements. These include: Fencing to hold stock on certain areas; developing water sources to make possible the use of ranges which cannot now be grazed because of lack of stock water; and constructing trails into areas which stock cannot otherwise reach. Better distribution of cattle on a range is obtained through riding. In this way stock may be moved from heavily grazed areas to undergrazed areas. One way of securing good distribution of stock is the proper use of salt on the range. Salt grounds are located in undergrazed areas where possible, usually at some distance from water. Cattle will travel from water to the salt and back again. They will, therefore, naturally graze the range around the salt grounds, thus using the forage more evenly. Salting is necessary on nearly all ranges to keep the animals in good health. Cattle which do not get enough salt become restless and are hard to handle. They develop perverted appetites and may eat harmful and poisonous plants. Stock on green feed in the spring require more salt than they do later when the forage has dried. Since sheep are constantly herded, at least under western range conditions, their management is considerably different from that of cattle. Sheep may be herded away from water to the lightly grazed ranges. Salting or fencing is not necessary to secure even use. Salt is necessary for the health of the sheep but is fed to them on the range, usually on the bed ground. The main point to keep in mind in the use of sheep ranges is to have all parts of the range used evenly. Pockets of good feed should not be completely grazed out and other areas left untouched. Drifting the band slowly over the range and bedding where night overtakes them is the best method. This is advocated on all national forest ranges. Only in rare instances, where bed-ground sites are scarce, as in dense timber, should the band be brought back to the same bed ground, and then not for more than three nights in succession. IMPROVEMENT OF THE RANGE The improvement of the forage through proper grazing practices has already been discussed. Range improvements ordinarily mean physical improvements such as fences, reservoirs, spring developments, wells, artificial reseeding, and the destruction of poisonous plants and range-destroying rodents. FENCES On ranges fences are of great importance in controlling the movements of stock, especially cattle and horses. Boundary fences are necessary to prevent unwanted stock from grazing the range. Division fences are used to divide the range into smaller blocks in order to prevent overgrazing of certain areas and to control the movements of stock. They are frequently used to divide spring, summer, and fall ranges. In some instances fences are built to prevent cattle from grazing areas of poisonous plants, and in still other cases the ranges of different breeds of cattle are separated by fences. WATER DEVELOPMENTS Reservoirs are usually constructed where water is scarce and where suitable springs cannot be developed. The commonest form of reservoir is an earth dam across a favorable coulee or gulch. When rains occur, a large pond is formed behind the dam which serves cattle for weeks or months later. Reservoirs permit the use of range which is so far from water that it is otherwise not possible for stock to use the forage. Springs and seeps which, in their natural state, furnish insufficient water for livestock can very often be developed by fencing and digging out the source of the water. The water is then piped into tanks or troughs where it is held for use as needed by stock. A spring which fills a 600-gallon tank in 24 hours provides adequate water for 50 to 60 cattle. On sheep ranges low troughs, set in series so that they all fill, are used most frequently. Wells and windmills are often necessary to supply stock water in certain locations where neither spring development nor reservoirs are feasible.

SALTING EQUIPMENT Sack crystal salt, rock crystal, or block salt may be used, and on cattle range should be put in containers. Salt left on the ground deteriorates rapidly and becomes mixed with earth which is consumed by the animals. Salt troughs may be made from logs or from heavy lumber. Strong boxes secured to posts or stakes also make good containers. Troughs or boxes should be strong enough to withstand rough treatment by herds, but light enough to be moved easily to various parts of the range. RESEEDING In order to bring back desirable vegetation on ranges which have been seriously damaged, or which are threatened with erosion it is often necessary to reseed. Crested wheatgrass, blue grass, and brome grass have given good results where conditions are favorable and moisture is adequate. Artificial reseeding is expensive, however, and the results often are disappointing. Consequently, range should be so managed through deferred grazing, seasonal use, and limitation of the number of stock that the native grasses and plants will not be damaged and reseeding will be unnecessary. POISONOUS PLANT CONTROL Medical treatment for poisoning is impractical and expensive and the animals may be dead before such treatment can be administered. It is necessary therefore that poisonous plants be eradicated or that the stock be kept off dangerous areas. The eradication of poisonous plants, like artificial reseeding, is expensive work. Many species, such as low larkspur, loco, deathcamas, and western sneezeweed, cover large areas and the plants may be so scattered and so numerous that control is virtually impossible. In the case of waterhemlock, which is extremely poisonous, and which is nearly always found in patches along creek or ditch banks, it is a relatively easy matter to dig up the plants or to fence dangerous areas. Tall larkspur is often found on limited areas and may be controlled by grubbing to a depth of 6 or 7 inches. The area must be gone over again the following year to remove plants which were missed the year before. At best, however, the grubbing of tall larkspur is temporary in effect and the plant has a tendency to come back after a number of years. RODENT CONTROL Rodents are responsible for a large amount of range damage. In the plains region, prairie dogs denude areas around their towns. Where these animals are numerous and the towns large, the amount of forage on the range is seriously reduced. In mountain parks and meadows pocket gophers cause range deterioration. These animals tunnel underground and eat the roots and bulbs of various plants such as onion grass, wild celery, and others. In addition, they store large quantities of roots in their burrows. Besides these three, other rodents such as jack rabbits, if numerous, consume much forage. Prairie dogs and ground squirrels can be controlled through the use of poisoned grain which is dropped in small amounts near the mouths of the animals' burrows, Pocket gophers may be controlled by the use of special gopher traps, which kill these animals in their burrows, or by inserting a piece of poisoned carrot or other root in the tunnel. HANDLING TO MEET LOCAL CONDITIONS Frequently, the principles of range management must be modified to meet local problems such as arise when sheep are placed on timbered range during periods of hot weather or on certain dry areas after rains. High water, which makes streams impassable to stock at times, may necessitate a change in the method of handling. There are many other problems peculiar to each range. The most common local problem is that of poisonous plants.

Poisonous plants cause large losses of livestock on western ranges. On the higher mountain ranges tall larkspur is the most harmful of these plants and annually causes the death of thousands of cattle. It seldom causes losses among sheep. Frequently, a change from cattle to sheep will eliminate losses by poisoning. Where this is not possible, it is a good practice to exclude cattle from larkspur range until the middle of summer since this plant loses some of its poisonous qualities after blooming. In some instances the amount of tall larkspur on a range has been decreased through sheep grazing. Low larkspur is also poisonous but does not often cause large stock losses. It is most frequently eaten where the range is overgrazed and good forage sparse. Sometimes a late spring snow storm covers up the better range plants, only the low larkspur extending above the snow. Under such circumstances, losses from this plant may be very heavy. Because of its abundance on certain ranges it is usually best to keep animals off such range until the better plants have grown sufficiently to furnish adequate feed. Loco weed, one of the plants belonging to the pea family, is another very poisonous plant on western ranges. Eating loco becomes a habit with stock, especially horses. Like low larkspur, loco is difficult to control. It pays to use the range properly since with the elimination of the grasses, loco has a tendency to become more abundant. Locoed animals seem to teach other stock to eat this plant. It is recommended, therefore, that those animals which have acquired the loco habit be taken out of the herd. The most poisonous individual plant is the waterhemlock (Cicuta). This plant, also known as wild parsnip, snake weed, spotted parsley, and muskrat weed, grows along creek banks and ditches. Fortunately it is not usually found in large quantity and can be dug out and destroyed. Another plant which causes losses, especially among sheep is the deathcamas (locally called soap plant, hog's potato, mystery grass, and poison sego), an onionlike plant with white or yellowish flowers. It seldom lasts beyond July and losses are most frequently confined to spring and early summer sheep ranges. The best method of avoiding losses from this plant is to keep sheep off ranges infested with deathcamas until other forage becomes sufficiently abundant and stock are not forced to eat the camas. Occasionally, lupine (blue peas, blue beans, old maid's bonnet or Indian bean) causes heavy losses. Under range conditions these losses are limited almost entirely to sheep. Eaten in moderate quantities, lupine is regarded as a valuable forage plant, but if sheep are very hungry when turned on the range, they often eat excessive quantities of this plant. The best means of preventing losses from lupine is to see that the sheep are well fed before going on lupine range. Protection against overgrazing is essential on such ranges. With an abundance of other plants available, there is little danger of lupine poisoning. Other poisonous plants which cause stock losses are milkweeds, oak or shinnery, chokecherry, Pingue or Colorado rubber weed, western sneeze weed, woody aster, bracken fern, and several laurels. Losses from these plants are nearly always the result of a lack of good forage plants. Overgrazing and the stunting or killing of the better forage forces stock to turn to these poisonous species. In addition to the poisonous plants, there are others which cause mechanical injuries. Barley grass and squirreltail grass, some of the needle grasses, also known as porcupine grass or needle and-thread, and the three-awn grass come within this class. The awns (the sharp-pointed needle-like seeds) work into an animal's mouth, nose, eyes, or body. Festering sores are produced and animals often are blinded. Animals do not eat these plants from choice after the seeds are formed. Where the plants exist, it may be necessary to graze the range before the awns become stiff and hard. Later in the season stock should be kept off such areas. These plants also affect game animals and cause losses among deer and elk. COORDINATION WITH OTHER LAND USES Watershed protection is an important item which must be considered when a range is grazed. Unregulated grazing eventually results in the destruction of the plant cover. As explained previously, this results in erosion, rapid run-off of water, smaller water reserves in the soil, and alternate floods and drying up of streams. The amount of water for irrigation and for use by cities and towns is made uncertain by overgrazing. Furthermore, the soil which is carried off the watershed through erosion will fill up irrigation reservoirs and ditches. Often the value of a watershed is greater than the value of the range, and it must be protected through proper grazing practices. Improper use of the forest for grazing results in the destruction of timber reproduction. Cattle damage young growth and small trees may be eaten by sheep or goats. Central bed grounds on sheep ranges and poor salting and overstocking on cattle ranges lead to the killing out of reproduction through trampling. Careless smoking or unsafe campfires, often result in the destruction of both range and timber. Similarly, burning the range with the idea of improving it usually causes complete destruction of small trees, and damage to the larger ones. Tests have shown that it leads eventually to the weakening of the forage plants, and decreases the value and carrying capacity of the range. Each year larger numbers of people use the forests and ranges for recreational purposes such as picknicking, camping, hunting, and fishing. It has become necessary, therefore, to leave some recreational areas ungrazed. Stock is controlled by herding or fencing the animals away from the favored areas. Big game animals, such as deer, elk, and antelope must be provided for in range management plans, where these wild animals use the same range as domestic stock. On most western ranges, especially on the national forests, there is usually enough forage during the summer for both livestock and game. In the rough canyons and ridges many pockets of feed not used by cattle and sheep form ideal game range. However, when deep snow forces game animals from the hills in the winter, frequently the only area available to them is a narrow strip of range between the valley ranches and the mountains. If this range is overgrazed by stock, game animals may starve, or they may invade the ranchers' fields and attack the haystacks. Sheep eat very much the same forage as deer and antelope. In order to provide for game, care must be exercised to see that winter range is not overgrazed. On properly used winter ranges, however, there is usually sufficient feed for both game and stock. Heavily grazed areas are not suitable for recreational purposes, and campers do not prefer to share their campground with a herd of range cattle.

|

Keep Good Plants Growing.

Providing Natural Seeding. Damage Through Overstocking. How Does Overstocking Affect Production Costs?

Tree Damage Through Overgrazing. A Good Rule.

Forage Wasted by Uneven Grazing.

How Can Good Distribution Be Secured?

Sheep Are Herded to Obtain Even Grazing.

How Can Ranges Be Improved?

Natural seeps are improved to provide adequate water for stock.

Poison Plants.

Method of Eradication.

Prairie Dogs. Gophers. Control Methods. Special Handling to Meet Weather Conditions.

Handling Stock to Prevent Poisoning. When Do Animals Eat Poison Plants?

Mechanical Injury From Plants.

Watershed Protection. Erosion Control. "Light Burning" Damages Ranges.

Overgrazing of forest areas results in deformed trees. Reserving Recreational Areas. Big Game Animals Must Have Range. Saving Forage for Wildlife. | |

|

SUMMARY Grazing is vitally important to many parts of the United States, especially to the West. Public ranges contribute materially to the welfare of many ranches. In order that ranges may continue to be productive, they must be properly managed. Range management must provide for the continued maintenance of a satisfactory stand of forage plants. Where these plants have been destroyed through misuse, the range should be so managed that these plants can reestablish themselves, and crowd out the undesirable species. The proper class of stock should be grazed on the range. In general, the less rugged, well watered, grass ranges are best suited for cattle. Sheep make better use of weed forage and utilize rough range better than do cattle. Also, sheep can get along with less water. The general habits of the different classes of livestock must be known as well as the type of range on which they are to be grazed. Occasionally the presence on a range of poisonous plants which affect only one class of stock, may make it desirable to run stock which is not subject to poisoning from those plants. The range should not be used too early. Plants should have a chance to produce seed; otherwise they will be destroyed. Stock should be held on the lower ranges until the forage on the higher areas has had an opportunity to develop. Ranges may be improved through deferred and rotation grazing, whereby a series of pastures are rested in rotation during the early part of the grazing season. The number of stock turned out to graze should be limited to the carrying capacity of the range. Grazing too many stock does not pay. It destroys the range and eventually reduces the profit to be made. Livestock should be distributed so that all parts of the range are evenly grazed. Water development helps. Also, on cattle range, salt should be so placed as to draw stock to the under-utilized areas. Sheep should be allowed to graze slowly over the range and bed down where night overtakes them. Returning the band each night to a central bed ground destroys range. Construction of fences aids in securing proper use, especially on cattle ranges. The construction of reservoirs, the piping of water from small springs and seeps into tanks, and the drilling of wells and the installation of pumping equipment are necessary to provide water on certain ranges. Artificial reseeding may be necessary when good forage plants cannot be reestablished through proper grazing practice. On ranges infested with poisonous plants proper handling of stock is necessary. Too early grazing and overgrazing have a tendency to increase both poisonous plants and stock losses. Other values must be recognized. The destruction of forage on watersheds results in erosion, floods, short water supply, and silting of irrigation ditches and reservoirs. Too heavy grazing often injures timber reproduction. Careless use of fire destroys timber as well as range. Certain areas which have a high value for recreation should not be grazed by livestock or should, at least, not be grazed to the extent that recreation values will be destroyed. Similarly, grazing of game animals should be so regulated that sufficient forage is left, especially on winter game ranges. |

|

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

ccc-forestry/chap11.htm Last Updated: 02-Apr-2009 |