|

CCC Forestry

|

|

Chapter VI

SYSTEMS OF TIMBER MANAGEMENT

|

SILVICULTURE is the science and art of establishing and managing forests to get the best timber products. Practices to obtain continuous timber crops are called silvicultural systems of management. The systems which may best be used depend upon the stand of timber, the product, and local conditions. When timber is cut indiscriminately, with no thought of reproduction or of plans for sustaining the yield, lumbering becomes a mining process. But when a desirable silvicultural procedure is applied in handling timber stands, then good forestry is practiced and lumbering becomes the harvesting of continuous crops of trees. |

Silviculture.

| ||||

|

STANDS Before studying the different cutting systems one should have a general knowledge of stands, types, and classification of forests.

Stand is a term applied to a particular part of a forest which has definite characteristics. Forests may be divided into stand classifications by considering two factors, species and age. There are two general classifications: Coniferous (generally called softwood) and broad leaf (commonly known as hardwood) stands. Coniferous stands are made up of cone-bearing trees such as pine, hemlock, and fir. Practically all conifers are evergreens. Broad-leaf stands are composed of the large number of tree species having broad leaves instead of needles. These, with a few exceptions, are deciduous (trees dropping their leaves in winter). When 80 percent or more of the crop trees in a stand are of one species, as pine or beech, then it is said to be a pure stand. If less than 80 percent of a stand is of a single crop species, it is a mixed stand. Classification of stands by age: If trees are of practically the same age, the stand is said to be even-aged. Most forests contain trees of all ages, from the seedling to old trees. These may be dominant, codominant, intermediate, or suppressed trees, as defined in the first chapter. Such a stand may be called uneven-aged, all-aged, or selection.

Forests are sometimes classified according to their origin. Trees grow either from seeds or from roots or stumps of other trees. A forest grown from seed is called a seedling forest, and a forest originating from sprouts or suckers is called a sprout or a coppice forest. Seedling forests grow a little slower, but the trees usually have better root systems after they are matured, and make a much better forest than a sprout forest. The stand growing from roots or stumps of old trees grows fast at first, but when the old root rots, as often occurs, the new tree has a poorly developed foundation of its own. The coppice forest produces fair poles, posts, and cordwood, but it is ordinarily not valuable for lumber. |

| ||||

|

In mature, even-aged stands it is often good practice to cut all the merchantable timber from the area in one logging operation. This type of cut is less expensive than removing the existing stand in several operations, since approximately a fourth of the cost of large-scale logging is in moving and setting machinery, building roads, skidways, camps, and buildings. Over a small area where trees from nearby forests furnish seeds for reproduction on the cleared portion, obtaining reproduction should not be a problem. However, character of the soil, location of seed trees, wind, and species must be considered. On larger areas it is usually necessary to reforest artificially. This can seldom be done satisfactorily by direct seeding, because of the many hindrances, such as poor germination, birds and rodents, and droughts. It is a more dependable practice to plant seedlings or transplants. This method, although costing more, eliminates much of the uncertainty, permits choice of stock, and provides proper spacing.

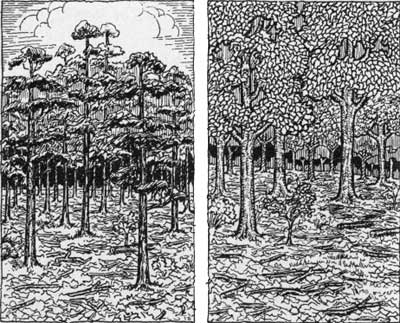

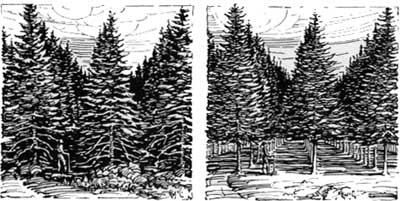

When local conditions permit, a modified removal plan may be used. One system of partial removal of the merchantable stand is called the shelterwood method of cutting. This method of removing the stand can be used successfully in even-aged stands that are wind-firm enough to prevent windfall after a part of the stand has been removed, and in which the species of reproduction desired is so tolerant that seedlings can develop under the shade of sheltering trees.

The logging operation, planned according to the shelterwood method, is begun by cutting 20 or 30 percent of the trees from the area. The remaining trees, with more space and light, have a tendency to produce better seed crops. The spaces opened by the first cutting offer good areas for germination of seed and development of seedlings. This first cut is called the opening cut or preparatory cut. Six or eight years after the preparatory cutting a further cut, sometimes called a seed cut, may be made. About half the original stand is often removed at this time. This cutting permits the establishment of new seedlings so that reproduction may be completed. Seedlings start in the new openings, and more light is afforded the reproduction already on the ground. The trees that remain bear more seed and protect the young growth from excessive sun. Within 6 or 8 years more the remainder of the stand may be cut off in the removal cutting. The entire stand may thus be removed over a period of approximately 15 years, and a strong crop of seedlings started on the way to produce a new forest which at maturity will have even-aged characteristics.

Another plan for cutting to obtain natural reproduction is called the strip method. The procedure under this method is to cut strips through the entire stand. The strips should extend at right angles to the direction of the prevailing wind so that the seeds may be carried from the remaining trees to the cut-over areas. After several years the strips may be widened by cutting other strips adjacent to them. After a series of successive cuts the entire stand will have been removed. The shelterwood and strip methods of cutting are not as popular in America as in Europe, where timber crops are managed more intensively. The time is coming when timber operators will be obliged to provide for restocking cut-over areas; then these methods may be practiced more widely.

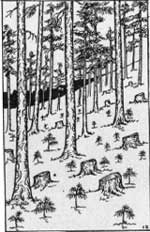

Natural reseeding of some species may also be obtained satisfactorily in clear-cutting operations by leaving seed trees scattered throughout the area which has been cut over. Seed trees are known also as mother trees, and are sometimes called "mammy trees" by the Southern Negro. These trees may be left standing singly or in small groups. Sometimes trees unfit for lumber are good seeders, and are windfirm enough to stand unprotected. If such trees can be found throughout the stand, there is no cost whatever for seeding. The effectiveness of the seed tree method of restocking depends largely upon the species. Trees bearing winged seeds, such as pine and maple, reproduce themselves over a wider area than do heavier-seeded trees like the nut bearers, because the winds help to disseminate the seeds. The practice of growing sprout forests may be advisable for producing some special products. Posts, poles, and fuel can well be grown from sprouts and suckers. Sprout forests can produce pulpwood in less time than seedling forests. Some pulp species, such as aspen, are good sprouters. It is practical therefore to clear-cut such stands, and to let sprouts and suckers restock the area. Managing stands in this way insures high productivity because of early maturity and elimination of reproduction costs. |

See Seed Trees, p. 129. Reproduction Problems. Planting Is Dependable.

The Removal Cut. Cutting a Strip at a Time.

"Mammy Trees."

See Kinds of Seeds, p. 99. Reproduction by Sprouts. Refer to p. 105. | ||||

|

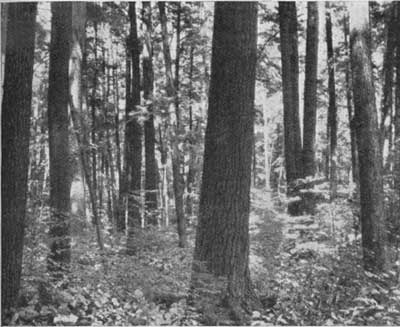

THE SELECTION SYSTEM Of the approximate 1,600 billion board feet of commercial saw timber in the United States, 80 percent, or 1,300 billion feet, is old growth. Much of this is in even-aged stands, having reached maturity long ago. This supply of old growth timber lies across a continent from the eastern market centers. For this reason the greater part of the East's timber requirements in the future will be furnished from the second growth forests of the East and South. These forests generally are uneven-aged, and ordinarily should be cut under a selection system of management. The uneven, or selection stand, as formerly described, contains all ages and often many species, and the selection system of management is especially designed to put such stands on a sustained yield basis. The principle of the selection system is to cut only the mature and defective trees and to reserve and protect the younger growth for future crops. Studies of growth rate will determine the amount of wood produced by the forest in 1 year, or in a number of years. The amount of timber cut each year should be no more than the amount grown in 1 year. If cutting operations are made every 10 or 20 years the harvest should not exceed the growth during those periods. The annual growth of the forest is distributed among all the trees, but for practical purposes the annual cut is made from among the large mature trees. To aid in regulating the cut, the forester determines the annual yield or the periodic yield, and then chooses a minimum diameter limit below which no trees are to be cut, but which will yield a harvest equal to the growth for the period. For instance on a forest of 1,000 acres the annual growth per acre may be 500 board feet. It does not pay to set up a logging outfit each year to remove only 500 board feet per acre, but in 10 years the yield amounts to 5,000 feet per acre. From tables which he has prepared, the forester determines the diameter limit which will yield an average of 5,000 feet per acre, or 5,000,000 feet for the entire tract. This diameter limit may be 12 inches, in which case only the trees with a diameter of 12 inches or more are cut during the logging operation. If the forester's calculations have been correct, he will be able, 10 years hence, to remove another 5,000,000 board feet from his 1,000 acres by cutting all trees above the same diameter limit.

Diameter cutting limits vary with the timber species and with the desired product. Spruce for pulpwood may be cut to a diameter limit of 8 inches, but for lumber the limit may be as high as 14 inches. The cutting limit is not always followed rigidly, as weed trees and invaluable species of smaller diameter may be removed in the cutting operations to improve the composition of the forest. These weedings may be done at little additional cost, and the product may be disposed of as fuel. As opposed to clear-cutting, the selection system has many advantages. In this type of cutting, the soil is always protected by forest growth and is not exposed to erosive forces as are clear-cut areas. Trees are harvested as they mature, and younger low-value trees are permitted to increase in diameter, height, and value before they are cut. By the removal of mature trees, space on the ground is opened in which seed may germinate, and the establishment of younger trees is stimulated. The ground and duff having been stirred in the logging operations, natural seeding is easier to obtain. The selection system is adaptable to farm woodlands and other small tracts as well as to large holdings. Even-aged stands may be converted to selection stands by a series of cuts made at intervals, and followed by natural reproduction or planting to arrive at a wide representation of ages. Often such stands are thereby changed to contain a number of age groups, in which case the periodic growth may be harvested by cutting clumps of trees rather than individuals. In most forests, the cutting system will not follow the bare essentials as outlined in this publication, but will include a combination of the more adaptable items of two or more systems. A forest composed of various products, species, or stands may demand special handling to obtain maximum sale values in the timber markets. Large tracts, therefore, are divided into units for cultural treatment and harvest. |

Sustained Yield for Selection Forests. Cut Matured Crop Trees. Growth Should Balance Cut. Determining the Growth. Calculating the Amount of Timber to Cut. Diameter Limits.

| ||||

|

The forest may be subdivided into units other than stands. These units may be for administrative as well as cultural purposes. A forest-land unit worked under a definite system of management frequently is called a working circle. This area may he quite small or it may be as large as 100,000 acres or more, depending upon the product, the market to be supplied, and the transportation problem. Management areas may have further subdivisions, which are governed by the rotation and the cutting cycle. A rotation is the number of years necessary to grow a tree crop to a given size or maturity. It corresponds rather closely to the age of the mature timber when cut, although the rotation period is usually longer than the age of the average tree when cut. This difference between age and rotation is brought about by the time required to secure reproduction, and it may vary from 1 to as much as 25 years when natural reproduction is depended upon to reproduce the stand. The cutting cycle is the period between cuts within the same area. In clear-cutting operations the cutting cycle and the rotation are essentially the same. But when an area is cut over in periodic harvests the cutting cycle measures the time between those harvests. If for instance a unit has its periodic growth harvested every 10 years it is being operated on a 10-year cutting cycle. Short cutting cycles require only small amounts of timber to be removed from any one acre during the harvest, but the cutting area must be large; whereas a longer cycle requires the removal of larger amounts from a smaller area. The subdivision determined by the cutting cycle is known as a logging unit. Blocks are topographic units which may form one or more logging units, or which may be part of a large logging unit. They are designated because of location—one block may be the area bounded by certain roads and streams, or may be an entire watershed or valley. Compartments are business units within a particular forest and are the basis for records of costs, yields, and profits. Large logging units may be divided into compartments. A further subdivision within the compartment is the subcompartment which is essentially a silvicultural or technical unit. Even further subdivision is done in intense forestry. For most extensive forest work, however, the compartment is the final division. |

The Rotation. Rotation Is Time Required to Mature a Timber Harvest. The Cutting Cycle.

| ||||

|

Regulation of forest usage should provide for a quality yield as well as for continuous quantity yield. Silvicultural cutting systems provide for sustaining the yield, and there are two major means by which this yield of forest products may be improved or increased. One is by protection to eliminate loss from fire, diseases, and insects; and the other is through cultural improvements which will stimulate the production of better products in less time. Improvement cutting in a timber stand is the fundamental cultural operation. Improvement cuttings may be made for the following reasons:

These six cutting classifications may overlap, but each one has its distinctive purpose. All have for their general purpose the production of a better stand and an increase in rate of growth. The cost of improvement cutting should be carefully considered before making plans for the operation. Unless there is a market for the product obtained in the thinning operation, the expense attached to improvement cutting may reduce the profit of the whole forest enterprise.

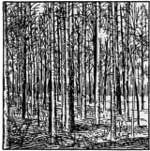

Thinnings: Improvement cuttings are designed to improve timber and to shorten the rotation (hasten growth). Thinning stands is one of the best means of gaining these objectives. Whether natural forests or plantations, whether pure stands or mixed stands, whether even-aged or all-aged, too many trees per unit area will result in poor growth and development. Thinning removes the forest growth that retards proper development of the crop trees. The first principle of thinning is the recognition of crop trees. Other tree growth should be removed as demanded by the stand. In addition to the crop trees on an area some inferior trees may be left for "trainers." These will help to develop straight, clear trunks in the better or crop trees. After the crop trees have grown sufficiently to form a close stand, the trainers may be removed in another thinning. Cutting out small trees to the advantage of larger ones is known as "thinning from below." In no case should thinning open up the stand so much that the crop trees will become excessively "limby." The canopy should be opened only enough to let in sufficient light for desired development of the crop trees. Weeding: In young mixed stands, commonly 5 to 20 years of age, undesirable species may retard development of the better species. Trees which have no value because of species or form are known as weed trees. These should be removed from the stand as early as possible. Weed trees in the young stand may be removed by use of brush hooks or light axes at little cost. If they remain in the stand until it is older, the cost of removal is greater. Sanitation: In older stands, some trees may become infected with diseases, or they may lose their value because of injuries. They take up space and consume food that could be utilized by crop trees. Removal of such infected trees through a sanitation cut is one of the important forms of improvement cuttings. Liberation cuttings: Strong, young growth of desirable species may be hampered by older growth of less desirable species or of unsatisfactory condition which overtops it. Wolf trees often rob young growth of its place in the forest community. Old forest trees, which have ceased growing, may retard natural increase of younger trees. Removal of the upper-story trees liberates the younger growth and permits further timber increase. Removal of top-story timber is called "thinning from above." In most cases, upper stories thus removed are merchantable timber, and this type of improvement cut may be compared to a simple selective-logging operation. Salvage cut: In cases where timber has been killed or seriously damaged by fire, storm, disease, or insects, the stand should be improved by removal of the damaged timber. Dead and injured trees which would decay and be lost may be salvaged (used) in this way. Dead and decaying trees are hosts to insects, and salvage cuts help to remove this hazard. Taking out the dead and weakened trees provides increased space and light in which young ones may become established and develop rapidly.

Pruning: In stands which are thick enough, natural pruning takes place. Because light is excluded by closed canopies the lower branches usually drop off. However, some species have very persistent branches (do not shed naturally), and it may be desirable to prune them. Branches which adhere to the trunk cause the timber developed in the tree to be knotty. If the tree is pruned in the sapling stage, the knots of such pruned limbs are confined to the heart of the tree.

When cuts are made to improve the stand, an effort should be made to use the timber and other products removed. There is not always a market for these products. With the exception of prunings and weedings of seedling stands, these products should at least pay for the cutting operation. In some cases a profit may be realized. Liberations, salvage, and thinning crop trees should yield profits. The products: Wolf trees, weed trees, and those removed in thinning may be used for posts, railroad ties, distillation wood, or pulpwood. Crop trees removed before maturity may be used for such products as poles and piling. Timber removed in a salvage cut may be used for many purposes, depending on its character and condition. Fuel wood can nearly always be disposed of, and much of the timber from improvement cuttings is fit for fuel only. Better quality timber can be used or sold as fuel if there are no other markets for it.

|

Weed Trees.

Cleaning the Stand.

A Stitch in Time Saves Timber. Left: Plantation unpruned; Prune for Clear Timber.

| ||||

|

In clear-cutting operations little marking need be done. If the seed tree method of reproduction is to be used, some marking system is necessary to prevent the cutting of "mother" trees. It would be a very rare stand if every tree were merchantable. It is not likely, therefore, that all trees old enough to bear seed will be mature enough or of sufficient value to cut. The trees with diameters too small to be merchantable or of little value because of poor form should be marked so that they will be saved from damage as well as from the saw. The older seed trees should be good seed bearers, windfirm, and free from serious insect and fungous infections. They may stand alone or in groups. Where the area is to be planted again there is no need for marking, unless it is desirable to leave trees for later seeding. The selection system of management requires complete marking. Loggers may not be competent in judging which trees to cut. It is the duty of loggers to fell and buck timber. When selection also is left to them errors are often made. It is well to decide upon minimum cutting diameters before beginning a felling operation, so that trees below a certain size will be left in the stand. There may be more than one minimum. Some species of trees are fairly well mature at a definite size while others of the same size should be left to grow for many years. For example, a lodgepole pine may be ready for market when its diameter reaches 12 inches, but a Douglas fir is a "youngster" at that diameter. If these two species are in the same stand, different diameter cutting minimums should be used. Marking for improvement removals may be done at the same time as marking for harvest. Marking is no job for a novice. Men should be trained by working with an experienced marker. A single worker may handle a marking job, but a crew of three is recommended. An expert and two unskilled blazers can do the marking at less cost than one skillful marker. A uniform system of marking should be used in a uniform stand. The area to be marked for cutting is often divided into strips, and the marking crew blazes, or labels in some other way, the trees to be cut in the strip. One mark is usually made 4-1/2 feet from the ground. The marks are all placed on sides of the trees that face the same direction. As the crew works back in the next strip, all the marks are visible. In this way, no tree is marked unnecessarily and trees missed in the first strip, may be seen by the crew while working back in the second. The strips are marked consecutively until the area is covered. In measuring diameters of standing trees, a caliper, diameter tape, or Biltmore stick may be used. This is a sure method, but rather slow. Some skillful markers place marks on the handle of the marking ax to measure diameters roughly. Trees are measured about 4-1/2 feet from the ground. This height is chosen to insure marking above the swell of the stump. This is about breast high and accounts for the common abbreviation in logging, "D. B. H.," which means "diameter breast high." Occasionally a marker becomes skilled enough to estimate tree diameters "by eye" accurately enough to eliminate the necessity of actual measurement. The mechanics of marking, like the methods of working, may vary. Sometimes paint may be used instead of blazes. Paint usually is applied with a brush, but by using a spray gun, paint marking can be simplified. When marking for thinning operations a code system of marking may be used, for instance, one spot for removal, two for pruning, etc. In some forests, especially those of Europe, a weatherproof tag is tacked to the tree. These methods are not so practical as marking with an ax. The ax is fast and economical. When the blazing method is used there is no paint to spill nor tacks to drop in the leaves.

In the Forest Service blazing system, a blaze is made on the tree about breast high, then low on the stump the bark is chipped off and a mark stamped in the wood. This mark serves as a record that the tree was officially marked to be cut. A special light weight marking ax is used. It has a sharp, narrow blade and opposite the blade, on the hammer head, the raised letters "U. S." which may be impressed in the wood by a sharp blow. This ax may also be used as a branding hammer to mark or stamp logs which have been scaled. |

For Selection Cuts, Mark Timber Trees. Minimums.

Measuring Diameters. See Measuring Instruments, p. 169. D. B. H. Blazing. Painting. Tags.

| ||||

|

A farm woodland or farmwoods is a tract of forest land maintained in connection with a farming enterprise. Farm woodlands are maintained to furnish fuel, posts, poles, and lumber for farm use, but often these products are cut in quantities large enough for sale in wood markets. When a forest area is cleared for agriculture, the more rugged and stony lands and those too steep for the raising of crops are permitted to remain in timber. In recent years many farmwoods have resulted from the abandonment of overworked, infertile fields. Seed from nearby forest areas has blown into these fields and the land has reverted to forest. The loblolly or "old-field pine" in the South seeds in rapidly on abandoned fields. State and Federal aid have made it possible for farmers to purchase seedlings cheaply or at cost of production from government-owned nurseries. Farmers have been quick to realize that forest cover protects the land from erosion and builds up depleted soil. Forestry on the farm is one phase of agriculture. It is concerned with the growing of timber crops. Trees and ordinary farm crops both are dependent upon soil, moisture, and sunshine. An essential difference, however, is that most farm crops have to be started every year, whereas timber, when rightly managed, yields a crop every year or every few years without removing the entire stand at any one time. In farming or in farm forestry the owner attempts to increase the quantity and quality of yields whether they be corn, oats, saw-logs or fuel wood.

The farmwoods is a taxable tract of land which if not properly managed may constitute a loss to the owner. Every farm, however, requires fuel wood, fence posts, poles, and lumber for repairs and small buildings. These may be cut as needed. Often a surplus, over and above what is needed on the farm, may be produced, and this surplus if properly disposed of in markets will provide a source of income. A farm with a good acreage of well-managed woodland can provide year-round employment for farm labor. In the winter when agriculture must necessarily be at a standstill, farm hands may be profitably employed in the harvesting of forest crops. In the Northeastern States, the maple-sugar industry produces an income for the farmer which in some instances is as great as that from his other crops. Hardwood forests supply wood for distillation plants, and in many eastern sections acid factories are almost wholly dependent upon cordwood harvested in farm woodlands. Minor products such as herbs, nuts, decorative material, and Christmas trees, and leaf mulch for small vegetable and flower gardens add to the woodlot's usefulness and income. Willows for baskets, lawn furniture, etc., may be grown along streams and in lowlands which are flooded periodically. This is a product which, because of high labor costs, is not profitable to the lumberman whose job is harvesting the mature timber crop. Trees as windbreaks and as builders and protectors of soil are important to the farmer. These values have been discussed in Chapter II. Worn-out land useless for agriculture may be planted to forest trees, and after a crop of merchantable trees has been grown and harvested the land may be cleared and tilled for agriculture. Small game is usually a part of the farmwoods, and the larger timber tracts may serve as game preserves. Many kinds of birds live in the forest, from whence they make their daily excursions to the farm land to feed upon weed seeds and destructive insects. The esthetic value of the farm forest cannot be overlooked. The farmwoods adds to the beauty of the countryside and increases the sale value of the farm.

The general principles of forest management apply alike to extensive forests and farm woodlands. The farmer, however, usually lives close to his woods where he can keep it under his constant care, whereas the owner of a more extensive forest tract may not always have so intimate contact with his property. Improvement cuttings, as discussed earlier in this chapter, may be practiced intensively in the farm woods and a ready use or market for the byproducts—posts, poles, or fuel wood—is usually found locally. Forest protection is a simpler matter in the woodlot than it is in large forest areas. The natural firebreaks of streams or plowed fields which ordinarily border the woodlot reduce fire hazard. The control of forest diseases is essentially the same in both woodlot and forest. The woodlot owner, however, can intensify the control measures and can use the diseased trees for fuel. In insect control under the most intensive management such direct methods as spraying and handing the trees may be practiced in the woodlot. These methods are rarely practical in large forest areas.

Woodlands are maintained on farms to produce timber and certain favorable influences on soil, temperature, and moisture conditions, and ordinarily they should not be used for grazing. In a stand of large even-aged trees, however, livestock in limited numbers may be permitted without resulting in much harm. The cool shade of the trees provides protection from the summer sun. A good practice is to include in the pasture enough trees to provide shade for livestock or to fence off small areas of woods for their use. In young timber, or in all-aged stands, or when reproduction is desired, livestock is decidedly detrimental to proper forest conditions.

When forest trees reach maturity, or attain the size required for the desired product they should be cut and either used or sold. The cutting operation should provide for the future production of the stand. Young trees should not be injured. When ample reproduction is not already started, planting of suitable young trees may be necessary. Unlike the owner of large forests, the farmer usually harvests his own timber crop. Each year he cuts enough fuel wood to provide for his own use, and when he has mature saw-timber trees he conducts his own lumbering operation. He is able, therefore, to practice the most intensive forestry. In an all-aged stand, cutting the larger, mature trees is the usual procedure, and reproduction occurs naturally. In even-aged stands, however, clear-cutting is often necessary, and a new stand must be established from sprouts or by planting. These practices apply more especially to large commercial operations. To provide a sustained periodic cut, and to insure a continuous supply of timber the farmer may convert an even-aged stand to an all-aged stand by removing the trees in small cuttings over a number of years. In this way reproduction is started in each cut-over area following the harvest, and the ultimate result is a stand of various ages.

The farmer who cannot estimate the contents of his trees in cords or board feet often sells his timber for less than it is worth. The sawmill man who makes the offer knows from his experience the amount of lumber that can be sawed from the trees. He usually allows sufficient margin on his estimate to insure a profit over and above his offer. If two or more prospective purchasers can be induced to bid for the timber, the owner stands a better chance of receiving a fair price. If the owner learns to estimate the volume of his stand as indicated in the chapter on Forest Mensuration, he will be able to bargain intelligently with the sawmill operator. The aid of a State extension forester may be obtained through the county agricultural agent for learning how to estimate standing timber or to measure logs. The sale price depends upon a number of factors: (1) The demand for the timber. If the woodlot is the only one in the locality growing the desired product, the farmer can obtain a fair price. (2) The kinds of trees and their quality. Different species of wood bring varying prices on the market. Walnut, for instance, is of greater value than pine. Diseased or insect-riddled timber cannot command a high price. (3) The location of the market. The buyer will not pay a high price if he must haul the timber long distances. If the seller must haul the timber to the market he should raise his price according to the distances and time of travel. (4) The cost of cutting. The logging of large tracts of timber costs less per thousand board feet than the logging of smaller tracts, as each individual enterprise has certain initial costs which must be charged against the total output. Steep rocky land is more difficult and costly to log than is flat lowland. (5) Cutting restrictions. When timber must be cut immediately the price is usually less than if the buyer permits the trees to remain standing in the woodlot until a more favorable time to cut, or until the market prices rise. The woodlot owner should always specify the date when all cutting should be finished. |

Farm Forestry—A Phase of Agriculture.

Products for Farm Use and for Sale. Year-round Employment.

Increasing Land Values. A Haven for Wildlife.

Converting Even-Aged to All-Aged Stands. Obtaining a Fair Price.

| ||||

|

SUMMARY Timber production should be managed so that continuous crops may be harvested. Growing timber is classified according to stand types. The principal classifications governing timber management are: (1) Even-aged stands, usually harvested by the clear-cutting system, and (2) selection stands, generally harvested by the selective system. In clear-cutting, all the timber is taken from an area in a single operation, and reproduction may be accomplished artificially (by planting); or the timber may be removed in deferred cuts, using the shelterwood method or the strip method of removal, thus providing conditions more suitable for the establishment of natural reproduction. In selection cutting, crop trees are removed periodically from the uneven-aged stands as they mature. Reproduction takes place naturally in the openings where timber was removed. In a forest area under management, working circles are established, upon which a definite cutting system is set up. On the working circle logging units are set off which are logged once in each cutting cycle. The quantity and quality of timber harvested from managed forests may be improved by cuttings not primarily designed for harvesting timber. These improvement cuts may be made to thin, weed, clean, liberate, salvage, or to prune stands. By exercising care and foresight in handling the trees removed from a stand in improvement cuts, marketable products may be produced which may be sold or used by the forest owner to make a small profit, or at least to pay for the improvement operation. The marking of timber for cutting should be done by an expert, since the success of any cutting operation depends upon the proper application of the principles of timber management. |

|

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

ccc-forestry/chap6.htm Last Updated: 02-Apr-2009 |